The coronavirus was rapidly spreading across the U.S., with more than 1,000 confirmed infections in 35 states, when Gov. Gretchen Whitmer got the call: The first two COVID-19 cases in Michigan had been confirmed.

It was March 10, about an hour after the primary election polls closed. Whitmer headed to the State Emergency Operations Center for a press conference to declare a state of emergency.

"The main goal of these efforts is to slow the spread of the virus, not to stop it," Whitmer told reporters in a sullen tone. "It has moved into Michigan."

Since then, the coronavirus has ravaged the state, claiming the lives of more than 2,400 residents and infecting more than 30,000 others. Hospitals have become overwhelmed, Whitmer ordered all schools and non-essential businesses closed, and more than 1 million residents have lost their jobs.

The question many people are asking has no easy answers: How did Michigan get hit so hard by a virus that originated in Wuhan, China, last year? And why did it get hit harder than its neighboring states?

Public health experts and epidemiologists interviewed by Metro Times say it's likely a combination of factors: Flights from Asia and Europe, the internationally connected auto industry, a primary election, a densely populated city reliant on public transit, and a delay in closing down restaurants, bars, and casinos — all while the virus spread undetected.

Figuring out how it happened is important in planning the next steps to combat the most destructive pandemic in a lifetime and rebuild the toppled economy.

"There will be many papers and books written about this, and our epidemiological health teams are exploring it right now," Dr. Steven Kalkanis, CEO of the Henry Ford Medical Group, tells Metro Times.

As one of only 15 states that had not yet confirmed a COVID-19 case, Michigan appeared to be faring better than most of the U.S. at the outset of the crisis. The nation's death toll had already reached 31 before Michigan identified its first confirmed infection.

But over the next several weeks, Michigan experienced a swift increase in confirmed infections and deaths, making it one of the hardest-hit states in the country.

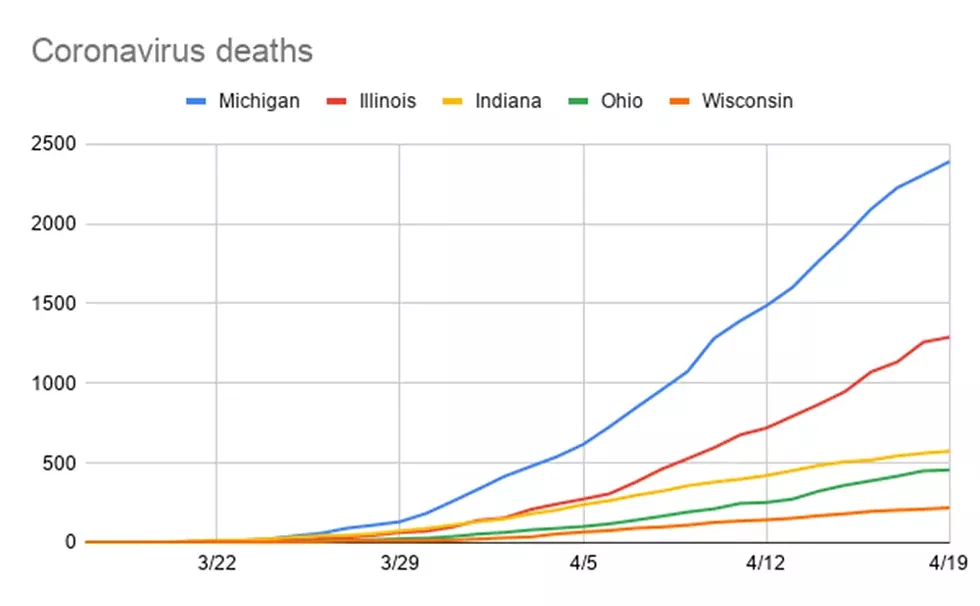

Now Michigan has a higher coronavirus death toll than Ohio, Wisconsin, Indiana, and Illinois combined. Only New York and New Jersey have more COVID-19 deaths.

What's now clear is that the coronavirus had already begun spreading throughout communities in southeast Michigan before the first case had been confirmed, public health experts say.

No one can say for sure how or when the virus reached Michigan, but experts believe that Detroit Metropolitan Airport played a role.

In early February, it was among 11 airports in the U.S. where travelers from China were diverted for health screenings and possible quarantine. In the months leading up the pandemic, the airport was also a popular hub for international travelers, many of whom had ties to the region's auto industry.

| State | # of cases | # of deaths |

|---|---|---|

| Michigan | 30,717 | 2,307 |

| Illinois | 29,160 | 1,259 |

| Indiana | 10,641 | 545 |

| Ohio | 10,222 | 451 |

| Wisconsin | 4,199 | 211 |

Source: Numbers reported by CDC as of Monday, April 20.

"Michigan is more international than I think people realize, given our auto industry and suppliers, as well as the airport," says Dr. Betty Chu, who is leading Henry Ford Health System's COVID-19 response. "Early on, we probably got a lot of folks traveling from other parts of the world that had outbreaks, whether it was from Asia or Italy, based on the kind of manufacturing we do here."

Michigan was slow to detect the first case because it only had 300 tests. The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention botched the rollout of its diagnostic testing kits, leaving many states without an adequate supply to test most people who were exhibiting COVID-19 symptoms.

On March 6, President Donald Trump falsely claimed that anyone "who wants a test can get a test."

With a critical shortage, Michigan established criteria that was so strict it prevented health officials from detecting community spread. The criteria limited testing to symptomatic people who had traveled to a coronavirus hot spot, or had contact with someone who had already tested positive. As a result, people who were infected locally were not getting tested.

By the end of February, the state had only tested five residents.

"Michigan, like many other states, experienced delays in obtaining collection and testing supplies, which affected our state's ability to provide widespread testing at the beginning of the outbreak," Lynn Sutfin, spokeswoman for the Michigan Department of Health and Human Services, tells Metro Times. "This level of testing would have provided a clearer picture early on of the spread of COVID-19 in our state."

Without a confirmed case, life carried on as usual. In early March, more than six weeks after the first coronavirus case was confirmed in the U.S., countless people attended parties, concerts, weddings, dances, and political rallies.

"There were several large parties and political rallies before the election," Dr. Joel Fishbain, medical director of infectious disease and epidemiology at Beaumont Grosse Pointe Hospital, tells Metro Times. "We have excellent historic information that prior to the shutdown we had a lot of people in close quarters."

Restaurants, bars, and Detroit's three casinos stayed open until Whitmer issued an executive order closing the establishments at 3 p.m. on March 16. By then, the coronavirus was spreading in southeast Michigan far more quickly than public officials believed.

Michigan has a higher coronavirus death toll than Ohio, Wisconsin, Indiana, and Illinois combined.

tweet this

Presidential candidates Bernie Sanders and Joe Biden held massive rallies in the week leading up to the first confirmed cases. Even Whitmer attended a packed March 9 rally for Biden in Detroit. "I'm gonna try not to start dancing, but I'm happy," Whitmer said from the stage, surrounded by people standing shoulder-to-shoulder with no gloves or masks. She later acknowledged it wasn't a wise decision.

State Rep. Isaac Robinson, a Detroit Democrat who died March 29 after a suspected COVID-19 infection, was campaigning for Sanders at nursing homes on March 6. Later that day, Sanders held a large rally at the TCF Center, which has since been turned into a field hospital for COVID-19 patients.

Four days later, on March 10, more than 2 million people cast a ballot in the primary election, sharing pens and polling booths.

"I do think the election had a significant impact on the spread," Fishbain says.

About 90 minutes after the polls closed at 8 p.m., Robinson and other state lawmakers received a text message: "We have 2 positive Coronavirus tests in Southeast Michigan."

Some political activists say the election should have been postponed. That would have delayed the meet-and-greets and rallies while the coronavirus was rapidly spreading across the globe.

"It was completely irresponsible to have the election," Bridget Huff, chairwoman of the Progressive Caucus of the Michigan Democratic Party, tells Metro Times. "The only result we have is widespread illness that we can't trace. Nothing good came from it, and lives were lost."

Health officials have traced suspected outbreaks to two March 6 law enforcement parties. At Bert's Warehouse Theater in Eastern Market, active and retired Wayne County Sheriff's officers mingled at an annual party with burgers, drinks, and jazz. One of the partygoers, Commander Donafay Collins, became seriously ill.

"This flu is no joke!!!!" Collins wrote on Facebook on March 11.

Collins died from the coronavirus on March 25.

State Rep. Tyrone Carter, who was also at the party, tested positive for the coronavirus.

By March 30, more than 41 sheriff's employees tested positive for the virus and two died, Collins and Deputy Dean Savard.

Also on March 6, about 100 people attended the Police and Pancakes event in Detroit, where another suspected outbreak occurred. One of the attendees, community leader Marlowe Stoudamire, died March 24 after testing positive for the coronavirus.

The city's health department didn't recommend quarantine for officers in attendance until March 20 — two weeks after the party. By then, the coronavirus was spreading quickly through the force. The number of confirmed positive cases among police officers rose from nine on March 23 to 170 on April 8, demonstrating how quickly the coronavirus spreads. Detroit Police Chief James Craig was also infected. Three members of the Detroit Police Department died from COVID-19: a Detroit police chaplain, a dispatcher, and Homicide Chief Jonathan Parnell.

"Somebody brought the virus into this community early on," Mayor Mike Duggan said on April 1. "It spread in this community before we knew it was happening."

The coronavirus has also devastated Detroit's close-knit ballroom dancing community, killing more than a dozen. In the second week of March, with no ban on gatherings, dancers mingled at the Paradise in Southfield, Club Yesterday's in Redford Township, and EARS Showplace in Hamtramck.

On the weekend before St. Patrick's Day, some bars were packed with revelers seemingly unfazed by the coronavirus.

Finally, on March 24, Whitmer ordered the closure of non-essential businesses by issuing a stay-at-home order.

It appears to be working. New cases and deaths have flattened, and the number of hospital admissions for COVID-19 patients is declining. As of Monday, about 1,200 coronavirus patients were on ventilators, down from 1,440 a week earlier.

"In the city of Detroit, we are beating this thing," Duggan said on April 17.

The number of new deaths in Detroit has fallen to under 20 a day. By comparison, the city was averaging about 35 daily deaths earlier in the month.

"The hard part about public health is when you're successful, it's really hard to see how many lives you've saved," Whitmer said at a press conference last week.

As the outbreak weakens, public health officials are urging caution.

"Our concern is that if we don't observe the types of precautions that we have been, there may be a second surge," Kalkanis says. "This is something we are trying to guard against in the immediate future. We're also concerned that there may be another surge next fall or in the winter."

With a severe shortage in testing kits, it's too early to know how many people are infected.

"We need to get more people tested," Whitmer says. "In order to safely open the economy, we have to know how much COVID-19 is present in the state."

But in recent days, Michiganders have begun to grow restless of the stay-at-home order, which Whitmer extended to the end of April. Last Wednesday, thousands gathered in Lansing for "Operation Gridlock," arguing the order goes too far and hurts small businesses.

Originally, organizers asked people to protest by staying in their cars to avoid spreading the virus. But many people got out of their cars regardless, standing closer than six feet apart and not wearing face masks. Some even brandished guns.

Whitmer said she was "disappointed" in the protesters, and that the gathering "may have just created a need to lengthen" the shutdown.

Stay on top of Detroit news and views. Sign up for our weekly issue newsletter delivered each Wednesday.