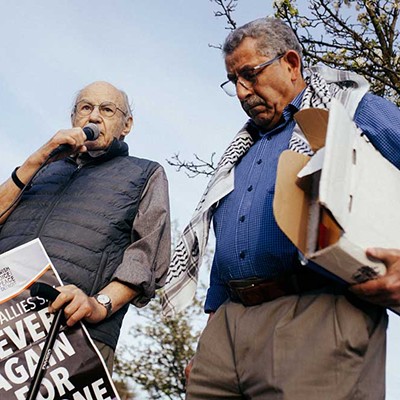

“There is a genocide going on in Palestine. This is a Palestinian dance and song,” Ayman Aboutaleb told the crowd before his dance troupe Thowra Dabke performed to “Zareef Al Toul.” As Aboutaleb explains it, the Palestinian folk tune is a love song about wanting to return home. For him, it represents Palestinians who have been displaced by Israeli forces and long for their homeland. A five-foot Palestinian flag hung in the background.

According to Aboutaleb, a Jewish man walked out during the performance, which was part of a multicultural event hosted by Detroit’s Congress of Communities. He told organizers the flag offended him because it showed “opposition to [Israel’s] existence.” Aboutaleb says he was asked to take the flag down and refused.

“I had a new [dancer], a Palestinian lady who had moved here less than a year ago from the West Bank performing with me… and I could feel her pain,” Aboutaleb says looking back on that day. “In her country back home, that’s what the occupational force does. They take down flags. She’s like, ‘How come I’m in a supposedly free country and now the same thing is happening?’ So I talked to the organizer and told him, ‘No, I’m not gonna take it down.’ This is part of my performance. It’s gonna stay here as long as we’re here.”

Aboutaleb is one of many Arab artists in metro Detroit using his art to raise awareness about concerns of the ethnic cleansing of Palestinians in Gaza and the West Bank. Dance, music, and visual art are ways for these artists to share their culture while ensuring that others bear witness to the atrocities committed against Palestinians by Israeli forces.

On October 7, Hamas in Gaza launched an attack on Israel, with Israel’s retaliation plunging the war into overdrive. However, the conflict stretches back at least 75 years to when Zionists violently forced more than 700,000 Palestinians from their homeland between 1947 and 1949 to create a Jewish-majority state, aka Israel. May 15, 1948, the day Israel was founded, is recognized by Palestinians as the Nakba, which means “catastrophe.”

“Everything about this is Arab. These are Arab melodies and Arab folk movements. I’m doing this for cultural preservation.”

tweet this

“We commemorate al-Nakba, the massacred villages, and ethnic cleansing [to] establish the Zionist entity,” Dearborn-based Palestinian artist Jenin Yaseen tells Metro Times. “We often describe post-1948 as the ongoing Nakba because the ethnic cleansing project has continued since then.”

Dabke is an Arab folk line dance that originated in the Levant — a region comprising parts of Jordan, Syria, Lebanon, Palestine, Israel, and others. The dance started with people in the Levant stomping on clay roofs to set the clay and over time it was synchronized to music as a celebratory dance, Aboutaleb explains. Dancers often link arms to form a line and hop or stomp to the music.

Aboutaleb, who is half Egyptian and half Lebanese, grew up on Detroit’s west side. He first started doing dabke in elementary school on a youth dance team and later joined the dabke team at the University of Michigan. He started Thowra Dabke in 2019 after teaching it at the Arab American National Museum (AANM). Thowra means “revolution.”

“I grew up in the Joy-Southfield area [and] went to Renaissance High School,” he says. “I had Arab culture at home, so I guess it’s something I sought out in my later adult years because I grew up in a different community.”

Thowra Dabke has 11 active members that include both men and women, though the troupe typically performs with six dancers. Aboutaleb is intentional about using authentic Arab music, clothing, and movement in his performances. Dancers sometimes wear the keffiyeh and clothing decorated with tatreez, a sacred Palestinian style of embroidery.

“Everything about this is Arab,” he says. “These are Arab melodies and Arab folk movements. I’m doing this for cultural preservation.”

While Aboutaleb says he has only had a few instances of people taking offense to him flying the Palestinian flag, Yaseen has had her paintings censored for mentioning Palestine.

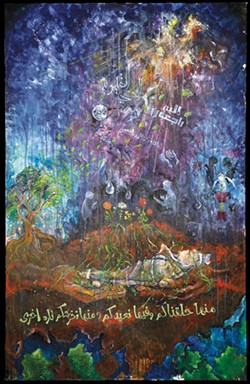

Her piece “Indeed, to our love we will return” was supposed to be featured in a traveling exhibit called Death: Life’s Greatest Mystery at Toronto’s Royal Ontario Museum (ROM) in October. The exhibit showcased burial rites across various cultures and Yaseen’s painting was part of an Islamic burial display. But the museum took issue with a small sliver of it that featured tatreez symbolizing a grave and the ghost of a Palestinian being pulled from the grave by soldiers. Inside the Palestinian person’s body, Yaseen painted a red poppy — the national flower of Palestine and symbol of resistance against Israeli occupation. The poppy colors (red, green, and black) resemble the Palestinian flag.

“There’s a saying that every poppy that you see on the ground is because the blood of a Palestinian has touched it,” Yaseen says. “The whole piece was around the sacred Islamic ritual that we do, which is burying the body almost immediately after they die... But it didn’t make sense to me to paint it without educating folks that Palestinians don’t have the privilege to even practice that sacred ritual because the Zionist entity practices this thing where they hold Palestinian bodies hostage. Their families don’t get the opportunity to bury their loved ones and grieve them properly.”

The ROM asked Yaseen and a group of fellow Arab artists in the Muslim display to remove “offensive” language and depictions. This included replacing “Palestine” with “West Bank” in personal anecdotes accompanying the display.

The artists refused, so the museum produced censored versions of the work without their knowledge.

When she arrived for the opening, Yaseen was pulled aside and showed a cropped rendition of her piece the museum intended to display instead. So she and the others staged an 18-hour sit-in until the museum agreed to show the unedited artwork. During the protest, Yaseen held a painting of the “controversial” section from her original piece with words added: “We deserve to grieve too. We deserve to live. We deserve to bury our dead too.”

The museum also altered a Jewish display in the exhibit in an attempt to be “fair.”

Following the demonstration, the ROM displayed the uncensored version of Yaseen’s piece with a trigger warning added. “The nearby panel includes an image dealing with death during conflict that some might find disturbing. If you prefer not to see this content, please go past this area,” a placard in front of Yaseen’s piece read. The museum also added additional disclaimers near Dina Omar and Malak Kanan’s displays of their family’s personal items and stories, saying the accompanying testimonies were based on “the experience of the contributors and not the museum’s.”

“There was not that type of disclaimer [on] any other pieces,” Yaseen says. “It was very blatantly racist.”

Yaseen was commissioned by Chicago’s Field Museum to create “Indeed, to our love we will return” for the Death exhibit and it had been displayed there with no issues before traveling to Ontario. Initially, she says, the Field Museum installation did not include Islamic burial rites, and Yaseen’s work was added as an afterthought. The Death exhibit was shown at the Field Museum in April 2023 and moved to the ROM in October. Yaseen says she was told by a ROM staffer they couldn’t show her work because “times are different now.”

“She said that my art incited hatred,” Yaseen remembers. “And that the Field Museum [was] able to display my art before October 7 but now, after October 7, it’s an entirely different experience. And I remember yelling, ‘For you, maybe! But we’ve been getting massacred for years. It’s not new to us.’”

Yaseen comes from a family of artists including her father and grandfather. Her cousin Ahmad Muhammad Yaseen went viral for painting on cactuses in his West Bank village.

Locally, she says most metro Detroit galleries reject her paintings for their political content. She has, however, exhibited at Detroit’s Swords Into Plowshares Gallery and organized shows at her alma mater, the University of Michigan Dearborn, with Students for Justice in Palestine.

“I work so hard on them and they’re just stuck here,” she says looking over the paintings crowding her Dearborn apartment. “It’s not always blatant but sometimes I find out later that it was [rejected] because I’m Palestinian and my art is deemed as hateful… As long as Zionism exists, I’m always going to be targeted. My identity is always going to be targeted and that’s just a privilege that I don’t have until, I feel like, Zionism and white supremacy [are] abolished completely.”

Her work often includes imagery like the poppy, handwoven tatreez patterns, and lions wearing the keffiyeh. She also paints portraits of Palestinian martyrs like Mohammed Sami Qariqa, an artist who was killed in October during an airstrike on al-Ahli Baptist hospital in Gaza. Hundreds of Palestinians had taken shelter in the hospital as the Israeli military retaliated following October 7.

According to Al Jazeera, more than 33,700 people in Gaza have been killed since then, including more than 13,800 children with around 76,400 people injured and more than 8,000 missing; at least 465 people have been killed in the West Bank with over 4,750 missing. Roughly 1,100 Israelis have also been killed with at least 8,700 injured.

The United Nations is investigating allegations that Israel’s actions in Gaza are genocidal, or “acts committed with intent to destroy, in whole or in part, a national, ethnical, racial, or religious group.”

Qariqa’s last post on Facebook before his death reads, “If something happens to us, remember that it is from the river to the sea.”

“We have a very strong martyrdom culture in Palestine,” Yaseen says. “Every life lost is more than just a number, and it’s an honor to die on your land.”

Despite some backlash, Yaseen and Aboutaleb hold steadfast in sharing their culture through their work and using it as a vehicle to talk about Palestine. Both stress that supporting Palestinians is not antisemitic.

“There’s a difference between antisemitic and anti-Zionist,” Aboutaleb says. “We’re anti-occupation. What we’re doing is against an occupational force. Talking about the people who live there is not going to take away from Jewish people. There were Jews living in Palestine before the concept of Israel, before 1948. It’s a holy land, all three religions passed through that area and all three religions were living in harmony… Arabs are also Semites. Arabic is a Semitic language. So as soon as that comes up, I say, ‘Why does this offend you?’ I try to challenge their way of thinking instead of just being like, ‘You’re an asshole.’”

On the other side of town, Spot Lite provides a haven for creative and marginalized communities on the Eastside of Detroit. The combination art gallery, record store, and nightclub often feels like a beacon that beckons communities of color, queer, and radical folks to gather as one. It also happens to be Arab-owned and managed.

Spot Lite resident DJ and general manager Aboudi Issa says he wanted to do something to try and help, or at least raise awareness, but it didn’t feel right to throw parties while Palestinians were being murdered. So instead, the shop organized several call-a-thons in late 2023 where more than 100 people called elected officials to demand a ceasefire in Gaza.

“We brought chairs and folding tables and everybody was straight up for hours, non-stop, just calling,” he remembers. “It was intense but it felt like we were doing something here that’s very small, but it felt good.”

Spot Lite also hosted screenings of documentaries like 1998’s Children of Shatila. The film follows two Palestinian children living in the Shatila refugee camp south of Beirut in Lebanon. Both children were displaced following the 1982 Israel invasion of Lebanon and the Sabra and Shatila massacres that left between 2,000 and 3,500 Palestinian refugees and Lebanese dead. Palestinians living in the Sabra and Shatila refugee camps had fled to Lebanon during the Nakba in 1948.

Issa is from Lebanon and came to the U.S. at the end of 2000. He remembers the horrific massacres and that information was not widely spread as it was before the time of social media. It’s part of the reason he feels called to make people aware of what continues to happen in Gaza.

“I grew up in Lebanon, and we had this happen more than once,” he says, adding, “It’s important to be in this movement of solidarity with the Palestinians… because I’m sure when it was happening in the ’80s and the ’90s, people had no idea. Seeing what’s happening over there and how the world sees it, is so eye-opening. The internet wasn’t that great [and] there wasn’t social media back then… but this is like the most heinous thing that ever happened in that area since it started back in ’48.”

He adds, “First, I’m a human being. That’s the number one thing. Being able to show it and raise awareness is very important, not just because they’re Arabs. Anywhere that it happens, we need to stand together. ”

“There’s a difference between antisemitic and anti-Zionist. We’re anti-occupation. ... There were Jews living in Palestine before the concept of Israel, before 1948. It’s a holy land, all three religions passed through that area and all three religions were living in harmony.’”

tweet this

But Issa is also a DJ, and music is his way of putting joy into the world. He’s been spinning Detroit-influenced house music mixed with Middle Eastern instruments for nearly 15 years. He started at house parties before his first official gig at the old Boom Boom Room in Windsor and has played all the regular spots around town like the Old Miami, Exodus Rooftop Lounge, TV Lounge, the former Grasshopper in Ferndale, and now Spot Lite.

While there may be a bit of survivor’s guilt — remorse for living a safe and comfortable life while Arabs in the Middle East are being bombed — he says he had to do what he’s always done as an artist, and that’s bring people together with music. So Spot Lite hosted a night of all-Arab DJs on February 10, with Barcelona-based Palestinian producer Maher Daniel as the headliner.

The night was part of A Real Arab Blueprint (A.R.A.B.), a series showcasing contemporary Arab art curated by Spot Lite owner Roula David and artist-curator Noura Ballout. The pair started the A.R.A.B. series in 2021 and hosted a slew of events under its banner featuring visual art, film, spoken word, and music.

Similar to Yaseen, Daniel saw the repercussions of speaking in support of Gaza on social media. He told Resident Advisor that he was bombarded with hateful messages after posting an Instagram story condemning both Hamas and the Israeli occupation of Palestine back in October.

Issa says he wanted to host the A.R.A.B. event to support Daniel on his U.S. tour in addition to raising money for the Palestinian Children’s Relief Fund (PCRF).

“Usually, we kept it educational and more serious but you can’t let them win both ways. You gotta have your fun too [and] sometimes people need some relief,” he says. “This is our line of work. This is what we do. We can’t just stay home. When you’re making [art], you want people to feel better. You want people to be happy. You want to be able to express yourself.”

That night Issa, Daniel, and Detroit-based DJ Salar Ansari played feel-good house music. Sweaty bodies swayed, shimmied, and bounced with joy, as friends embraced, held each other close, and shared collective gratitude for being alive. The event raised $2,000 in collaboration with food pop-up Dawat for PCRF.

“I just want people to know the reality of what’s going on over there,” Issa says. “We want people to feel like they’re a part of something that’s bigger than us and, hopefully, leave more loving, more kind, and more open-minded. And for the people struggling who want to get some relief, I hope they can do that with dancing.”

After some thought, he adds, “Arabs, Palestinians — we’re all people. We all just wanna live and have a good time.”

Yaseen thought showing her work at the Field Museum would be her “big break” where she would finally be “a real artist.” Unfortunately, that wasn’t the case but it hasn’t stopped her from using art as a revolutionary tool.

“A lot of [Palestinians] are in diaspora, a lot of us are stuck in refugee camps, a lot of us are still back home, [and] a lot of us are in refugee camps back home a few feet from where [we] were forcibly displaced,” she says. “We don’t have the language sometimes to communicate with one another because we’re all so spread out. But it’s art that's able to connect us. It’s these symbols that have been embedded in our culture and our traditions that are able to connect us… I have a duty as an artist to keep producing… to bridge the gap between the diaspora and our people back home that [the] Zionist entity and white supremacists are trying so hard to break.”

Aboutaleb also sees himself as a cultural ambassador.

“I don’t want it to be another thing that gets taken as someone else’s culture and they try to claim it,” he says of dabke. “That has happened with food, music, garments…. I want enough people to know that this is an Arab folk dance and it stays that way.”

Aboutaleb teaches a three-month-long dabke workshop at Dearborn’s AANM. The four-week-long classes are separated into three levels — beginner, intermediate, and advanced. Once a student completes all three levels, they can join the Thowra Dabke team. The only caveat is that Aboutaleb refuses to teach Israelis.

“I can have Jews on the team, but not people who believe that Israel is their homeland because if you believe that, you’re part of the occupation,” he says. “If you own property there, you are displacing people who are there. I’ve had Filipino, Asian, white, Black, Mexican, Cuban, people from all over taking my classes. I have nothing against letting non-Arabs perform [dabke]. It’s not to be exclusive, it’s just for cultural preservation.”