Reporter’s notebook: What literacy means

[

{

"name": "GPT - Leaderboard - Inline - Content",

"component": "35519556",

"insertPoint": "5th",

"startingPoint": "3",

"requiredCountToDisplay": "3",

"maxInsertions": 100

}

]

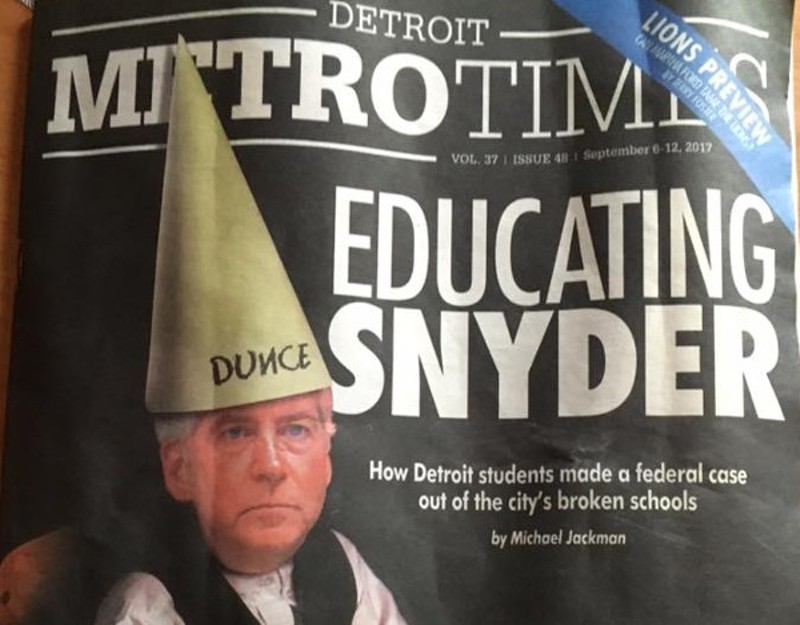

When Metro Times decided to dedicate its cover story to the “literacy lawsuit” filed on the behalf of Detroit school pupils, it was something we felt more invested in than many other topics.

It’s probably because we’re in the business of writing that makes us a little bit sentimental about the two R’s. Even in this day of almost instantaneous global audiovisual communication, reading and writing are still potent and magical, allowing people dead for hundreds of years to speak to us, or offering a durable medium for our thoughts to travel far into the future, long after we’re gone.

What’s more, reading and writing are not just fancy motor skills that allow us to order a Big Buford at the drive-through or describe the plate of food posted to Facebook. Words are the tools of thought. While it may be possible to think something through using only images, it seems like it would take a long time to do so. Words are efficient. What’s more, reading and writing help us order our ideas, a fact known by anybody who’s refined their thoughts by writing in a journal or composing a letter to a friend. (You might compare it to the way a computer stores data when it can only process so much.)

We got some similar insights when we interviewed one of the experts involved in Detroit’s literacy case, Dr. Elizabeth Birr Moje. She is dean of the School of Education at the University of Michigan. But the Bay City native got her start teaching high school courses in history and biology. That’s where she found that many of her students had trouble with reading and writing. And this was not in a poverty-stricken, majority-minority district such as Detroit’s: Most of the students were white and came from relatively prosperous working- and middle-class families.

She told us, “I found that when I would put texts in front of students within my disciplinary subject areas — government, biology, general science — that they either struggled to read them, read them in lackluster ways, refused to read them, or simply couldn’t read them.” She also found that many of her students found it difficult to write anything beyond a basic five-paragraph essay. (Yet, as the director of school theatrical productions, she found that those same young people could quickly read scripts with comprehension, engagement, and passion, and could memorize and perform the texts.)

She found herself “perplexed by how to more fully engage young people with reading and writing text.” She told us, “As a young teacher, I didn’t know how to help them reach those literacy skills. That’s what led me back into graduate study to focus on literacy in particular.”

She’s now an expert in the field, and she told us a lot of what we expected to hear: Literacy is critical to becoming a productive member of society, it helps us engage in challenging civil discourse, it allows us to understand the basic texts of our country, or to understand important news, such as evaluations of air and water quality.

Surprisingly, when asked point-blank about what literacy is, Moje called it the “$64,000 question.” While many laypeople might say literacy is obviously about being able to read and write, the term is much more widely debated among literacy scholars, and they range from the sort of person-on-the-street answer (reading and writing) to broader definitions that equate literacy with knowing something, such as how to use computers (“computer literacy”) or an ability to analyze, evaluate, and create media (“media literacy”).

“I’m more conventional in my definition of literacy,” Moje told us. “I don’t reduce it to reading and writing alphabetic print, but I do suggest it’s the encoding and decoding of permanently rendered symbols.”

It doesn’t exactly roll off the tongue, but it’s a very precise way to put it.

It’s worth noting, of course, that when conditions such as those outlined in the literacy lawsuit prevail, kids don’t have a fighting chance to crack that code. The pat claims of critical commenters that the problems in Detroit’s under-resourced schools boil down to lackadaisical students, troubled families, and moral failings don’t stand up to scrutiny.

“Those skills are never practiced autonomously,” Moje said. “Literacy always has an ideological social quality. … Schools matter. We know that good instruction matters. We know from research that the system really shapes what teachers are able to do, what resources they have access to, but also resources that are less tangible, like resources of time and all sorts of pieces to building strong supportive systems for teachers.”

We can’t believe that this needs to be pointed out, but, judging by some comments, apparently it does, so we’ll quote her on it: “We know that schools that don’t have teachers don’t do as well as schools that do have teachers.”

She goes on to add, “There are lots of pieces that would fly in the face of the claim that it’s all about individual children or their families. Children come to school with differing experiences, and there’s a very famous study that shows that children who live in poverty or lower income levels enter school behind their more resourced counterparts. They’re starting school at a disadvantage. But schools actually make a difference.”

She clarifies, however, saying, “But only if they’re well-resourced, well-run and stocked with excellent teachers. Teachers make a huge difference. We know that good instruction above all else makes a difference. But you have to be able to get the good instruction to children. People don’t learn literacy on their own. Nobody learns to be literate by themselves. It’s not possible. Literacy is social.”

And for Moje, being “literate” means having access to texts, such as laws, rules, reports, and much more. And why is that important?

“Without access to those texts,” Moje said, “we live at the whim of others who do have access.”

“For me,” she told us, “literacy is about access to shared symbol systems and it then shapes the way we see the world. That access shapes with how we talk with one another: It marks some people as ‘in the group’ and some people as ‘out of the group,’ and it shapes access to information and being able to challenge information.”

So literacy is a sort of “marker” of our membership in the group that does the encoding and decoding. When you think about it that way, the civil rights aspects of the lawsuit become all the more clear.

“When multiple people share understanding of a symbol and others don’t, some people are members of community and some people aren’t," Moje said. "If you have the codes and you can make sense of them, then you can be part of a community, and if you don’t then it’s much harder to interact with that community.”