If the walls of the home at 1538 Junction Street could talk, they would tell the story of five generations of working-class Detroiters. The modest, two-story barn-style house in Southwest Detroit was purchased in 1907 by a pair of Irish immigrants and passed down through their descendants — willed first to their daughter, who would teach at nearby Western International High School for 42 years — to her daughter, a dental hygienist who married Henry Ford's chauffeur. In the early '90s, the house was left to that Irish couple's great-great-grandson, Joseph Bates. At the time, it was worth $18,000.

From the beginning, paying property taxes on the home was a struggle for Bates, who was then in his mid-20s and working a supermarket job at minimum wage — $3.35 an hour. Bates paid what he could when he could, but says that in the early 2000s, work became scarce and he fell behind. It was also around that time that changes were made to Michigan's delinquent property tax law, setting into motion what has turned into a tsunami of tax foreclosures in Detroit. Countywide, more than 160,000 homes have been foreclosed, seized, and put up for auction since 2002, with the bulk of them in the city.

"The penalties and fees kept accumulating, and there was no way I could actually catch up and get my head above water," says Bates.

As is standard procedure, the Wayne County Treasurer's Office foreclosed on Bates' home after he fell behind on three years of taxes, and in 2012 the house was sold at auction for $600. But when the buyer recognized the amount of work he'd need to put into the property to make it fully livable, he agreed to sell the house back to Bates on a land contract for $4,000. It took Bates more than a year to scrape together the money he needed to regain ownership of his family home.

That was 2014. Over the next two and a half years, Bates' health would worsen, leaving him unable to work and keep up with his yearly $1,300 tax bill. His home was foreclosed once again and sold at auction last fall for $15,000.

Then, as has become common practice at the thousands of occupied tax-foreclosed homes auctioned off each year, some strangers showed up and told him to leave.

"They said they were there to clean out the yard," recalls Bates. "I had no idea what was going on ... Two weeks later, they came back with four people to throw me out and told me to go to a homeless shelter."

What has become clear to Bates in the months since he was forced from his home is that the property never should have been foreclosed to begin with.

Because Bates was living under the poverty line, he was eligible for a poverty tax exemption that would have allowed him to avoid paying property taxes altogether — but he didn't know such an exemption existed. His home, which was in such poor shape that multiple rooms were unlivable, was also more than likely overvalued — but he didn't know he could appeal the assessment. Property records show that city assessors had determined the home on Junction was worth almost $12,000 in 2012 — the same year it sold at auction for just $600.

Bates believes the real cash value of his home at the time was somewhere in between, at $2,400. If he's right, it means the city over-assessed his property by more than 400 percent — a possible violation of the Michigan constitution. The document says that no property can be assessed at more than 50 percent of its market value, but researchers looking into the issue have found that, in Detroit, illegal assessments have become the norm. And because the city has one of the highest tax rates in the country, the effects of improper assessments are amplified, pushing more and more people into tax foreclosure.

According to a soon-to-be-published study conducted by a visiting Wayne State University law professor and an assistant professor of economics at Oakland University, Detroit assessed 55 to 85 percent of properties in violation of the Michigan constitution every year from 2009 to 2015. And the assessments were, at times, far above the legal limit: The study found that in 2010, assessments were on average more than seven times higher than the legal limit. In 2015, they were more than twice higher.

'People knew these foreclosures were unfair, but they were unable to articulate they were more than unfair — they were unconstitutional.'

tweet this

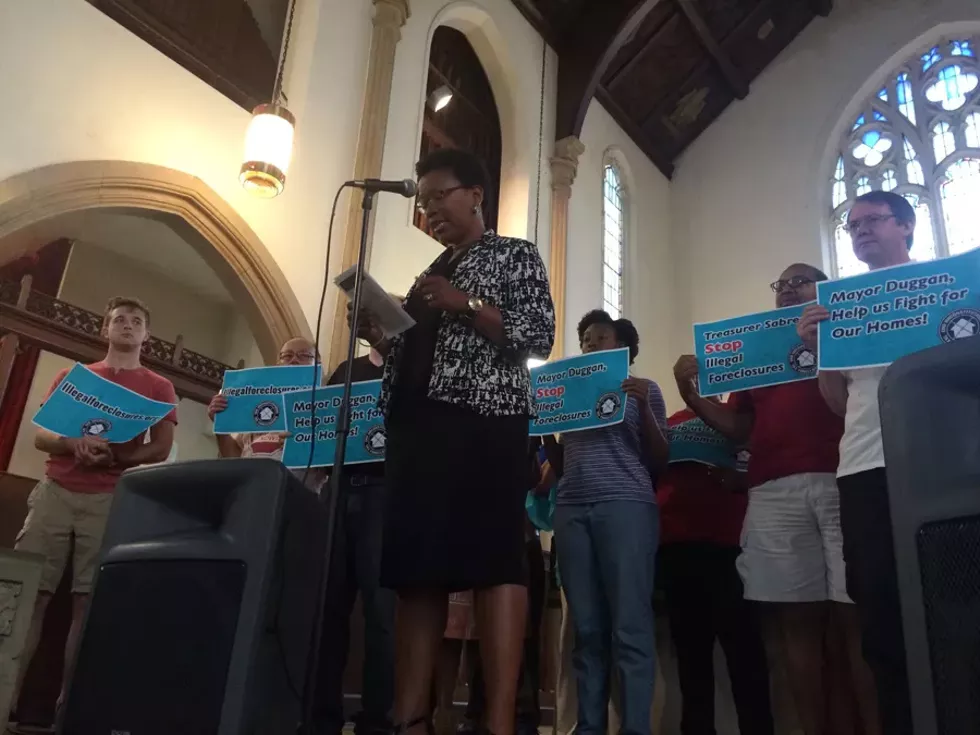

"Those numbers are completely and utterly shocking," study co-author Bernadette Atuahene told a crowd at a July 8 news conference at a church in Detroit's New Center neighborhood. "People knew these foreclosures were unfair, but they were unable to articulate they were more than unfair — they were unconstitutional. And that's important because when you speak to authorities about [the root of the tax foreclosure crisis in Detroit], the answer you'll get is that it's because Detroiters are poor, because of high unemployment, because of poor job training. That's not what's happening. This is a structural injustice happening that starts with the assessor's office in Detroit."

Atuahene's findings mirror claims made in a lawsuit filed last year by the American Civil Liberties Union and the NAACP against the City of Detroit and others. The lawsuit says the city failed to reduce property assessments to reflect massive declines in home values following the recession. Detroit's top attorney has said the claim is "fatally flawed as any potential claim was discharged in bankruptcy." Butch Hollowell also called the suit "recklessly irresponsible," because "it would violate compliance with [Detroit's bankruptcy] Plan of Adjustment, indefinitely prolong state oversight of city operations and threaten basic city services to all Detroiters."

As the ACLU suit looks for a legal remedy for Detroiters who've lost properties that were overassessed, a coalition that has mobilized around Atuahene's work is hoping to arrive at a political solution. The Coalition to Stop Unconstitutional Tax Assessments has called on Mayor Mike Duggan's office to offer compensation to those victimized by the inflated assessments and to issue an across-the-board cut in assessments of lower-value homes.

Duggan has taken some steps toward addressing the assessment problem in response to Detroit property owners who have long complained of inflated assessments that drive up their taxes. In January, Detroit’s assessor's office wrapped up a several year reassessment of the more than 250,000 residential properties in the city. Assessors used a combination of field visits and aerial and street-level photography to determine the value of homes, whereas in the past, the office had arrived at its conclusions through averaging available sale prices in whole neighborhoods or sections of the city.

According to Atuahene, by law the office should have been physically looking at 30 percent of properties each year to come up with taxable values. Why this wasn't happening is not clear, but a 2012 Detroit Auditor General report suggests a lack of resources may have been to blame. The report that looked at the office from 2008 to 2011 found it was losing staff each year. It also determined the division to be "inefficient, ineffective, and lacking in some areas."

City officials in January said that, as a result of the parcel-by-parcel reassessment, more than half of Detroit's homeowners would see their property taxes go down by up to 10 percent in 2017. The year before, 95 percent of homeowners saw reductions of 5 to 15 percent. But Atuahene's latest research suggests assessment accuracy has mostly just improved at high- and mid-value homes, while problems at the city's poorest addresses persist.

"When we re-ran the numbers in 2016, we found that over 95 percent of houses worth $18,500 and below are still being assessed in violation of the Michigan state constitution," says Atuahene. "Once you get it wrong on the lower side, it's a bigger error because the home is worth so little."

But assessment errors on those low-value homes can prove devastatingly costly for low-income Detroiters who are more likely to face foreclosure. And though they technically can appeal, Atuahene points out that it's affluent people who are more likely to appeal assessments. They're also more likely to win than poor and minority populations.

With that in mind, the Coalition to Stop Unconstitutional Tax Foreclosures is asking Duggan to direct his assessment division to cut assessments for all properties worth less than $50,000 by 30 percent. The group also wants some form of compensation for people who were unconstitutionally assessed and already lost their homes to tax foreclosure. After hearing from more than a hundred Detroiters impacted by foreclosure, the coalition found that residents would be most interested in financial compensation or in Detroit Land Bank homes they could renovate and live in.

The coalition also wants to see federal Hardest Hit Funds that the city has earmarked for demolitions used instead to pay the tax bills of people who were unconstitutionally assessed and now face foreclosure. And it is asking that Wayne County Treasurer Eric Sabree put a temporary halt on foreclosures until the city can ensure that delinquent taxpayers in the process of foreclosure were not subject to unconstitutional assessments.

For Wayne State University law professor and Damon J. Keith Center for Civil Rights director Peter Hammer, Detroit officials committed an injustice they must remedy.

"The city knew that it was over-assessing those taxes ... which means that this wasn't just a clerical error," Hammer says. "This is an intentional decision that was made not to adjust properly the property taxes, not to make available the poverty tax [exemption] and knowing that that was going to drive historic Detroiters from their homes — not by the ones or twos — but by the tens of thousands as part of the struggle of displacement."

The mayor's office would not comment on the coalition's demands, citing the pending litigation with the ACLU, but a spokesman did say Duggan has made efforts to keep people facing foreclosure in their homes since taking office. The mayor had a hand in crafting an interest rate reduction program officials credit with saving nearly 50,000 homes from foreclosure over the past two years. And the city has launched a buyback program for residents whose foreclosed homes are now owned by the Detroit Land Bank Authority, with 180 homeowners expected to regain ownership this year.

But Atuahene contends that payment plans and home buybacks are not a solution for people who were foreclosed after their home values were improperly assessed.

“They’re putting you on a payment plan for taxes you shouldn’t have to pay in the first place,” she told a woman who managed to escape foreclosure this year. “The properties should be reassessed and the taxes should be recalculated retroactively.”

Duggan has previously indicated that he is not open to considering reimbursements or reparations for tax foreclosures involving possible unconstitutional assessments because he says homeowners could have appealed their property's assessed value.

Of course, they would have needed knowledge of the system to do that — and in Bates' case, he says he was not so lucky. As he stood before a crowd on July 8 to share his story, his voice broke as he delivered a message for the mayor:

"Because we're poor and are ignorant of your laws, don't make us feel like we're not wanted in Detroit," Bates said, holding back tears. "We wanna be treated as everybody else — equal. Look at our homes, look at what we can pay, and assess what we can pay ... look at how we have to live, because some people have to eat bologna every day in order to pay their bills."

Since last fall, Bates has been staying with some family friends around the corner from the house he lost. But he says that family is struggling too. They've faced at least one water shutoff due to unpaid bills, which can get rolled into property taxes in the city of Detroit.

Bates sees the writing on the wall, and says that on what is the 110-year anniversary of his family's legacy in Detroit, he could be packing his bags for elsewhere.

"I may have to move down south to get back on my feet and live with my sister," he says. "I love Detroit. I wish I could stay, but I'm not sure I'll able to."