It's that time of year again: A redemption deadline for Wayne County property owners facing foreclosure for failing to pay three years' worth of taxes has passed, and those living at places where a homeowner did not make arrangements to start paying off those back taxes now run the risk of losing the roof over their heads.

An estimated 17,000 homes — the bulk of them in Detroit — this year received foreclosure notices. The majority of those homeowners managed to reverse the process by a June 7 deadline, but an estimated 4,000 occupied homes are expected to be sold in the Wayne County Tax Foreclosure Auction this fall, according to information provided by the county at a tax foreclosure roundtable. With the U.S. Census putting an average of three people in a household — that means 12,000 Detroiters could be seeking shelter come October.

Since 2002, at least 150,000 Detroit residents have lost their homes for failure to pay taxes, or because they were renting from a landlord who, unbeknownst to them, had not been paying. In May, United Community Housing Coalition tax foreclosure prevention project coordinator Michele Oberholtzer explained the larger implications of the ongoing tax foreclosure crisis as she prepared a group of volunteers to reach out to Detroit residents affected:

"What we have is a system that is losing the city and the county money. It's resulting in people losing their homes, it's leading to vacancies and evictions, it's leading to concentrated properties in very few hands (with the Land Bank now owning more than 100,000 homes)," Oberholtzer told the group gathered at the nonprofit's offices. "And we have this downhill spiral that makes it harder for everyone in the community."

The Wayne County Treasurer's Office says it has been working in tandem with groups like UCHC to address the issue by keeping more people in their homes and on the tax rolls. This year, it knocked on thousands of doors in an effort to notify people facing tax foreclosure of their payment options, and it promoted a reduced-interest payment plan to help some residents lower the interest on their late-paid taxes from 18 percent to 6 percent.

But as the treasurer's office takes some steps to help people avoid tax foreclosure, Wayne County's budget actually depends on money made from selling foreclosed homes at auction and collecting late-paid taxes and resulting fees. The money helped the county stave off bankruptcy two years ago and is included in budget projections through 2019.

Bridge Magazine explained how the county profits from foreclosure in an article published early this month. When people fail to pay their tax bills, municipalities like Detroit turn the bill over to their home county — in this

That surplus, along with money made off selling homes and other properties at auction, winds up in something called the Delinquent Tax Revolving Fund (DTRF). Massive transfers from the fund — $92 million in 2014 and $79 million in 2015 — helped the county eliminate its accumulated structural deficit while it was under state oversight two years ago. And it appears the county has continued to rely on the money: Treasurer Eric Sabree in a May email to Metro Times credited the DTRF with allowing him to "distribute $24 million to taxing authorities including school districts and libraries and parks, etc." Budget projections outlined in the county's recovery plan show transfers from the fund are expected to provide the county about $30 million per year through 2019.

But despite the budget boost late-paid taxes and homes sold at auction bring, officials say the county has far more to gain from people paying their taxes on time. Wayne County Chief Financial Officer Tony Saunders says that's why the county drafted its recovery plan with the intention of curbing reliance on the money made from tax foreclosures, implementing

"The entire point of the recovery plan was to use Delinquent Tax Revolving Fund transfers from the past to eliminate the accumulated deficit and then take in structural surpluses through the modifications that we made," said Saunders. "Moving forward, we're not as reliant on those (DTRF) revenues because we've made some pretty massive structural changes on the budget front and on the financial front."

A spokesman for the county, however, acknowledged that surplus funds from foreclosure fees and the auction are still coming in and being put to use — as in the case of the money Sabree said this year went to school districts, libraries, and parks.

"Now we use the surplus on singular items and projects, where in the past it was going to help other things," said county spokesman Jim Martinez.

Still, Saunders maintains that "if folks didn't lose their homes because they were able to pay their taxes, Wayne County financially, economically, and from a quality-of-life perspective would be in a much better place."

If that is indeed the case, the argument among those in favor of changing the status quo is this: If Wayne County is making extra money from the foreclosure process, wouldn't it make more sense to use that money to keep people in their homes?

That's the case being made by Jerry Paffendorf of Loveland Technologies, who has called on Detroit Mayor Mike Duggan, Wayne County Treasurer Eric Sabree, Wayne County executive Warren Evans, and Detroit's foundations to work together to put an end to the practice of selling occupied homes at auction.

Paffendorf — who ran for treasurer unsuccessfully in 2015 — has come up with a proposal he says can solve the problem and has presented it to the each of the three officials and the city's major charitable organizations. The plan involves bundling all foreclosed occupied homes into one unbuyable block and passing them through the auction, after which authorized organizations like housing nonprofits and land banks can work with occupants to turn them into owners and preserve the property. The city's philanthropic and foundation community, in Paffendorf's vision, could put up the money needed for the treasurer to remove the occupied homes from the auction.

Last year, selling such homes brought $19 million to the county, according to treasurer Sabree. Paffendorf has learned that about 3,300 occupied homes were sold at an average of $5,750 a piece to reach that total, meaning that, if 4,000 occupied homes are expected to be sold at auction this fall, the

If foundations can come together "to provide hundreds of millions of dollars to prevent the art at the DIA from being sold," says Paffendorf, they can invest in helping Detroiters save their homes, because it "would have a much bigger impact on the [people] living in the city's neighborhoods."

Setting aside the moral questions surrounding the practice of selling the homes people live in because they or their landlord didn't pay taxes, Paffendorf says it behooves the powers that be to overhaul the tax foreclosure system because it costs the county money in the long term.

For instance, studies have shown that selling occupied homes at auction leads to displacement

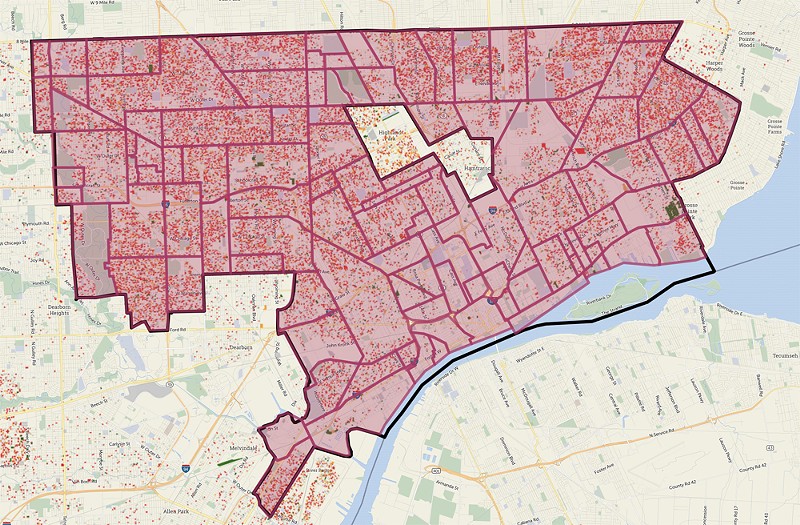

Vacant homes also often eventually require costly demolition. A separate Loveland report shows there are more vacant homes today in Detroit than when the city started its ambitious demolition effort in 2014. The culprit, as Paffendorf sees it, is tax foreclosure.

As responses to Paffendorf's proposal trickle into his email inbox, the data guru says he's seen "middling positivity" from city and county leaders — and some finger pointing in the direction of other offices. Mayor Duggan, for instance, said overhauling the system is up to the county treasurer, and treasurer Sabree told Paffendorf his hands are tied on what to do with the funds generated from

Paffendorf, in a response to Duggan, noted that he's historically appeared to wield considerable power in brokering deals that fall outside the scope of his office. And he reminded Sabree that it is the treasurer alone who controls the Delinquent Tax Revolving Fund.