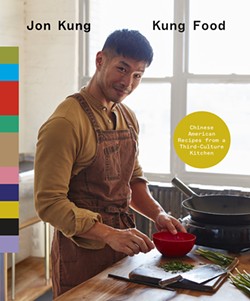

Jon Kung was once a law student searching for a creative outlet. In 2020, he started posting cooking tutorials to TikTok, and today, he teaches his 1.7 million followers to prepare everything from Thanksgiving Turkey Congee to Lion’s Head Meatballs. His page includes a series on tomato sandwiches, a library chronicling different spices, and a set of dishes based on anime characters.

Kung defines himself as a “third-culture cook,” and he says his goal is to decolonize the way ethnic food is viewed in the United States. On Oct. 31, he’s set to release his debut cookbook Kung Food: Chinese American Recipes from a Third-Culture Kitchen. The book revolves around recipes blending cultural traditions, ingredients, and flavors (a favorite is the Motor City-inspired “Faygo Orange Chicken,” utilizing the popular made-in-Detroit pop), and explores how food shapes identities, and how a multicultural identity can shape it.

Born in Los Angeles, Kung grew up moving between Hong Kong and Toronto. He started cooking in Hong Kong, poaching eggs in the microwave as early as age 4. But growing up, he says he was “afraid of the kitchen”.

“I had no idea what I was doing, but I was cooking anyway,” he says.

A connection between his high school in Hong Kong and Concordia College, a small Christian college in Ann Arbor, brought Kung to Michigan. Finding Concordia too small, he transferred to Eastern Michigan University.

At EMU, Kung studied theater and creative writing, graduating amid the 2008 recession. He hesitated on pursuing a career in either field, and instead did “what any panicked undergrad would do” — he turned to law school.

Kung was not alone in this move. In 2010, the New York Times reported a 20% spike in the number of people taking the Law School Admissions Test, illustrating a larger trend in graduate school interest due to the recession.

While attending the University of Detroit Mercy School of Law, Kung started teaching himself how to cook.

“It was like the one creative thing that I could do” Kung says. “Nothing else seemed justified in taking time away from studying.”

He adds, “I was missing food from back home. Detroit during that time didn’t have much for Chinese restaurant options.”

Kung never intended on becoming a professional chef; he just had to eat, and wanted to eat good food. He says he studied cookbooks, watched a lot of YouTube tutorials, and drew on his experience eating authentic Hong Kong cuisine and traditional Chinese dishes.

Memory became a baseline for what his cooking should taste like.

“If it didn’t taste like what I remembered or as good as I remembered, then I needed to keep trying,” Kung says.

Kung started documenting his food on a short-lived blog that caught the attention of local restaurants like St. CeCe’s Pub. Soon enough, he was working pop-ups at bars, cafes, and empty storefronts around the city of Detroit, hauling with him precooked food, a commercial induction burner, and a plug-in soup warmer.

In 2013, Detroit saw a trend in pop-up restaurants, and Kung felt at home in that scene. “We all were helping each other out,” he says. “In a way that just benefits as many people as possible … we were doing the best that we could to make our neighborhood just, like, a nicer place to live.”

Kung eventually started his own pop-up in Eastern Market, Kung Food, where he hosted private dinners and taught underground cooking classes — all while evading the health inspector. “I was just this gangly little cook, sneakily cooking people food,” he says.

After graduation, Kung had a job offer lined up, as long as he passed the state’s bar exam. He failed the test twice — the first by 3 points, the second by 2. The next day, Kung got dumped by his boyfriend.

“I basically blacked out for a month and then woke up in Costa Rica with a yoga teacher certification,” Kung says wryly, “as you do.” Kung decided not to retake the bar exam and, despite the student-loan debt, he shifted to cooking full-time.

“Ultimately, I felt like my heart was in food,” he says.

For 12 years Kung worked, managing his own pop-up and working in local restaurants like Standby, Lady of The House, Gold Cash Gold, and Takoi. He ran Kung Food for six years, until the COVID-19 pandemic forced him to close down.

At the same time, Kung described seeing kids on TikTok talking about how scared they were. He had downloaded TikTok in 2018 and started observing trends on the platform. He had the sense that it was “something special,” he just didn’t know where he fit in yet.

“[The pandemic] seemed very big and people seemed very scared, and I was like, well, what can I do? I know how to cook,” he says. “So I’m going to help the people that are stuck in their homes learn how to cook.”

Kung focused on the basics: how to break down a chicken and turn it into soup, or make casseroles and clay pot rice, or turn vegetable scraps into broth — even “how to make frittata with all the garbage in your fridge,” he says. “Really survival stuff.”

“I felt like at that point in time it was everyone’s duty to do everything that they can,” he says.

Kung soon shifted away from basics into more complex dishes, showing off things he had done at his pop-ups in Detroit. This new content took off and Kung “cautiously dove in.”

“The stove makes me happy,” he says. “I look at that stove, and I say: Oh! Racist bought me the stove. Thank you, Racist.”

tweet this

Kung says he had no intention of going viral. “It was really just a creative outlet,” he says. “I didn’t know what a content creator was. I did not know about this path as a viable career until I was already in it.”

In 2021, Kung got his first brand deal with Funimation, an anime streaming service. He was tasked to turn his kitchen into “Naruto’s Ramen Chowdown,” and produced dishes based on characters from the hit ninja series, like Naruto’s Miso Ramen, and Sakura’s Red Beet and Shoyu Ramen.

“That was my first real job with anybody,” he says. “And that was when I realized: Oh, this is a career.”

Kung’s videos also became more political, addressing issues like racism and xenophobia amid the flood of hate fired at Asian Americans during the COVID-19 pandemic.

According to the FBI, anti-Asian hate crimes increased by 77% from 2019 to 2020. The influx cost Asian restaurants an estimated $7.42 billion in lost revenue, as they experienced a significant decrease in traffic, according to a study published in the journal Nature.

Kung says he started dealing with online hate almost immediately, but he maintained a positive outlook, finding the silver lining, and quipping back.

“Engagement is engagement is engagement,” he explains. “Any response, positive or negative, equals more views — and more money. The algorithm does not know the difference.”

Kung says that he likes to set aside part of the revenue and buy himself something really nice. Then he mentally attributes that thing to the hate comments he received. For example, he bought himself a fancy stove for his home, which he uses for all of his videos.

“The stove makes me happy,” he says. “I look at that stove, and I say: Oh! Racist bought me the stove. Thank you, Racist.”

Kung describes the stigma surrounding Chinese American cuisine as being rooted in racism and classism. He said that for years, Chinese American food has been devalued because the labor of Chinese people is devalued in general. This has halted the development of the cuisine.

He says that American food has already undergone a culinary renaissance. It came in the form of classically trained, western, white male chefs opening gastropubs and New American restaurants, taking techniques and ingredients from other cultures.

“They started using pork belly. All Chinese people have been using pork belly for a long time,” Kung says. “As did Mexican people, and as did Caribbean people.”

Kung wondered why Chinese American food didn’t take part in this trend. “What if Chinese American food got to have that same level of play and experimentation to respect as just plain old American food?” he asked himself.

So, Kung dove into multicultural cooking, this time using Chinese food as a base.

“It took me kind of stripping away the ego that came with chasing authenticity,” he says, putting air quotes around “authenticity.” “Realizing that, you know, I’m not just somebody who cooks Chinese food, because I’m not just somebody who is Chinese. I am Chinese American. And what does that mean to me? And what does that mean to examine Chinese American food for all of its good parts, for all of its bad parts, for all of it?”

The title of Kung’s book refers to “third-culture” cooking, which started as a reaction against the term “fusion.”

He says that fusion cooking has always referred to dishes made by a person who studies one type of cooking, delving into its ingredients, techniques, and dishes, and in the end produces something that may be novel, but is ultimately very superficial.

“Fusion cuisine is cute. Like: Fusion cuisine,” he says, mockingly. “Isn’t that adorable?”

Kung’s disdain for the term is shared broadly. According to an article in the Los Angeles Times, the term “remains a hydra of a slur,” an “insultingly reductive” marketing technique that ignores a plethora of Asian, Asian American, and Pacific Island cultures.

Kung views third-culture cooking as being more nuanced, respectful, and informed. He says that its knowledge is cultivated through either lived experience or deep and effortful research. Its dishes aim to represent people on both sides of the culture. “You just start to develop nuances and understanding that are very, very deep in both cultures,” he says.

He describes how the mixing of cultures allows chefs to make “something that you could not get in Korea and to make something you could not get in Mexico or Nigeria. But at the same time, it’s very much Korean or Mexican or Nigerian. But it’s also American.”

With his new book, Kung is once again stepping into the unknown. Kung says he plans to continue cooking, and making content, developing new recipes and redefining what Chinese American food can be.

You can follow Jon Kung on TikTok at @jonkung.

Subscribe to Metro Times newsletters.

Follow us: Google News | NewsBreak | Reddit | Instagram | Facebook | Twitter