The rising 12th grader chalked the change up to the management company — red is a prominent color in the logos for the five other charter campuses New Paradigm runs. But then she noticed something else. The grades the site said her school served: K-8.

Hall was weeks away from starting her senior year — she was meant to be apart of UYA's first graduating class — and now she suddenly found herself questioning if she even had a school to return to.

The new information was startling, but more so was the lack of communication and clarity. Two days after noticing the changes on the website she and her mother were told, via text, to come to the school for an important — but cryptic — Monday evening meeting for all "rising seniors" (9-11th grade were told to come to the school Tuesday).

It was here that she — and about 25 of her peers — found out that the high school — where they planned to show up for the first day of classes in two weeks — was closing.

"They call about everything else, but they don't think to call about closing the school down?" the teen, who has been at UYA since 9th grade, questioned after the meeting.

Jada Hall doesn't know where she will go for her senior year. She says the "best" schools aren't accepting seniors. pic.twitter.com/dUKUrG4y6Z

— Allie Gross (@Allie_Elisabeth) August 22, 2016

WHILE THE INSTABILITY FELT by the high schoolers at UYA Monday may seem like an isolated incident, it's in fact one of several topsy-turvy occurrences that have transpired over the past few months — and really years.

UYA, which opened its doors to sixth-grade students in the fall of 2010, came into local spotlight in the spring of 2015 when staff made public their desires to unionize. The decision was ill-received by the school's then-charter management company, New Urban Learning (NUL), and by April NUL announced that it would be leaving UYA.

"We believe that a larger charter management organization with more resources and fresh ideas would better enable UYA to meet its 90-90-90 goals — game changing goals we believe are attainable," the letter forwarded to the staff by Lesley Ester Redwine, the CEO of NUL, read.

The news was crushing for staff, as the resignation of NUL meant that should the staff vote in favor of a union (which they did a few weeks later) they would have nobody to bargain with. At charter schools, the management company is the employer not the school board — which means the departure of the management company is also the departure of the employer the staff hoped to bargain with. More dispiriting, the departure of NUL (the employer) meant that everyone on staff was terminated and had to re-apply for their jobs. At the start of the following school year, only 17 of the school's 68 employees had been there the year prior.

While these were clear signs of instability there was one consistency. After leaving the school as NUL, Redwine created a new management company — InspirED Education — and submitted an RFP to run the school under the new company. The board decided to go with Redwine's new company. In other words: the management company more or less stayed the same, but the obligation to bargain was gone. Redwine argued that she did not need to bargain because InspirED was not at the school at the time of the union vote and that the majority of the staff had changed since then.

What complicates this story — and the instability seen at UYA — is what occurred next. In March the National Labor Relations Board issued a complaint, alleging that Redwine created an "alter ego corporation" (InspirED Education) in order to avoid collective bargaining with the UYA staff, who voted overwhelmingly in favor of union representation in the spring of 2015. By May the school's charter authorizer, Bay Mills Community College (located about 342 miles aways from the school), sent a letter of revocation, saying the school was at risk of losing its charter.

In June, reports Michigan Radio, the school board struck a deal with the authorizer, which promised to get the school back into "good standings" if it dropped Redwine's management company and found a new company to run the operations.

This is where things get particularly tricky.

At the end of June Redwine signed a settlement with Michigan ACTS promising to bargain with the staff; however, two days before the settlement agreement was signed, the UYA board announced their intentions to sign a contact with New Paradigm, a local charter management company run by self-proclaimed "education entrepreneur" Ralph Bland. While the board essentially had to find a new management company to keep the school open, the move once again shook up the school. For a second year in a row, the entire staff was fired and asked to re-apply for their jobs, and once again the obligation to bargain was voided. The big difference this time around is how it would so directly affect the students.

AS PARENTS AND STUDENTS streamed out of the UYA cafeteria Monday evening the spirit of defeat was palpable. While some, like Hall, had a sense of what was to come, many felt blindsided.

"It's real messed up, my son has been here since sixth grade and we just found out today that they are eliminating high school," one angry parent, Kelli Vaughn, said, on the verge of tears. "What are we supposed to do? Another black school closed down. More black kids cannot be educated because they want to do what they want to do. Where are our kids going to go?"

Parents walking out of UYA mtg after finding out new charter mgmt co is closing the HS weeks before new school year. pic.twitter.com/bgYPfHYGCw

— Allie Gross (@Allie_Elisabeth) August 22, 2016

Why the school would wait till the end of the summer to share this news was a question that kept cropping up. Were the kids — and their educational experiences — so insignificant that it could be relegated to the bottom of a list, an afterthought to share before the school year starts? Is transience just an accepted part of going to school in Detroit? Parents and students mulled over these questions as they tried to make sense of the news they had just heard.

"I don't care that they're closing so much that they waited until the end of the summer to tell us," said rising senior Aleka Simmons, who last fall brought UYA into the public spotlight when she snapped a picture of her commute to school featuring what she says is a daily occurrence: Six children crammed onto a 39-inch seat. (While WXYZ, who picked up the story, criticized UYA for putting the students in a dangerous situation, the school's then-head of school Eric Redwine — Lesley Ester Redwine's husband — told the station that he viewed the seat cramming as a good thing as he was happy to have so many kids enrolled in the school).

Simmon's frustrations were reiterated by her classmates.

"They waited like two weeks before school was starting to do this. If they wanted to do this they should have told us at the end of last school year," said Antwan Ramsey, a rising sophomore who was at the meeting with his older brother Antone, a rising senior.

The boys said they didn't know where they would go next year, but that the management company had given them a list of suggestions.

New Paradigm (new mgmt)handing out a list of schools kids can go to. Front + center? DEPSA a charter they also run. pic.twitter.com/GsaibUffcg

— Allie Gross (@Allie_Elisabeth) August 22, 2016

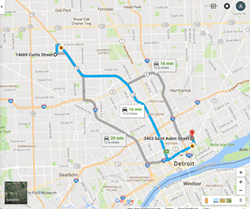

At the top of the list? Detroit Edison Public School Academy — a charter school run and founded by New Paradigm's CEO Bland. It also happens to be 13 miles away (or 1 hour and 40 minutes away via public transportation) from the UYA campus.

For some who have been following the saga of UYA — like former 10th grade English teacher Melanie Ward — this is exactly what was to be expected.

Ward, who was terminated in June with the rest of the staff, says she had a feeling back then that New Paradigm had no intention of keeping the high school open.

UYA, which opened in 2010 with a $5.8 million donation from the Wayne and Joan Webber Foundation, was simply too small. The middle school had opened a high school and an elementary school in the fall of 2013 and by the 2015-16 school year the growing campus (K-11 last year) was snug with high schoolers basically tripping over the elementary school students. For a portion of the 2015-16 school year, then CEO Redwine had the 10th and 11th graders bussed to the Charles Wright Museum and Detroit Historical Museum for their classes to free up some space (it was explained on the school's website as an enrichment opportunity).

Ward says the original RFP for a new management company specifically noted that they were looking for someone who could secure a new site for the high schoolers. She even says a bid, from Equity Education, promised to do this. But then, she says, the board decided to go with New Paradigm and suddenly the language demanding a new site disappeared.

"It was like the problem just went away and now they [New Paradigm] didn't need it in their bid," Ward, who is today working as the principal of a school in Dearborn says. "People figured Bland wanted to send those kids to DEPSA. We didn't have the facility space, they had nowhere to put the kids so that would be an easy way out."

When she and fellow staff members implored Bland and board members about the rumored high school closure at a June board meeting they were told "no comment." (At this meeting the board also said they still needed to negotiate a contract with Bland, as he wanted more than 10 percent of the school's per pupil funding in exchange for his services, and the board said they were unwilling to go that high. According to a recent article by Michigan Radio, Bland ultimately got his way and is getting 13 percent of the per pupil funding).

Considering each public school student is worth about $7,000 in state funding, getting UYA students to attend DEPSA — a high school that already exists — without having to cover overhead costs for a new high school facility, is a big win for Bland.

This may also be why he would not speak with MT. At the meeting Monday we approached the New Paradigm CEO to find out why he never called us as he had promised after the June special board meeting and when he decided to close the high school. He said he "got busy" in regards to the lack of a phone call and then refused to speak with us about anything school related. His bodyguards intercepted at this point, creating a scene that resembled nothing of a typical K-12 (or 8?) campus interaction, but one that did not shock those who have worked with Bland and New Paradigm before.

"I used to work for Ralph Bland when I taught 5th grade in Detroit," one former DEPSA teacher, who left for another teaching opportunity and spoke under the condition of anonymity, told MT. "Our school was in an old tomato processing factory and was run with the same mentality. Education was treated as a business - kids were the products whose most valuable assets were their test scores. Educators were expected to provide automated, scripted instruction and were constantly observed to ensure that protocol was followed. Nothing about this surprises me as the Blands' see kids as dollar signs and not much else."

THE CLOSING OF UYA'S high school highlights failures in Detroit's school landscape. UYA was created in 2010 by Doug Ross the founder of NUL and the University Prep network of schools. New Paradigm, the new management company, is the work of Bland. Both of these men have been touted for having model charter schools in the city. They are supposed to be — according to the media and foundations who have given them funding — the schools that do it right. They're marketed as the ones that don't settle for overcrowded schools and classrooms, who don't close at last minute leaving students in a lurch, who work and communicate with students and their families to ensure the best possible outcomes.

And yet families, as they left the meeting Monday had little semblance of where to go next — and more notably wanted anything but these "model" charter experiences.

"He's just trying to switch us to his schools so he can still get the money from us and I don't want that," said Hall, who is looking at University High School in Ferndale and DPS's Communication & Media Arts for her senior year. "I feel like the schools he's trying to suggests to us are just like UYA and I don't want to go to a school like UYA anymore."

This post has been updated.