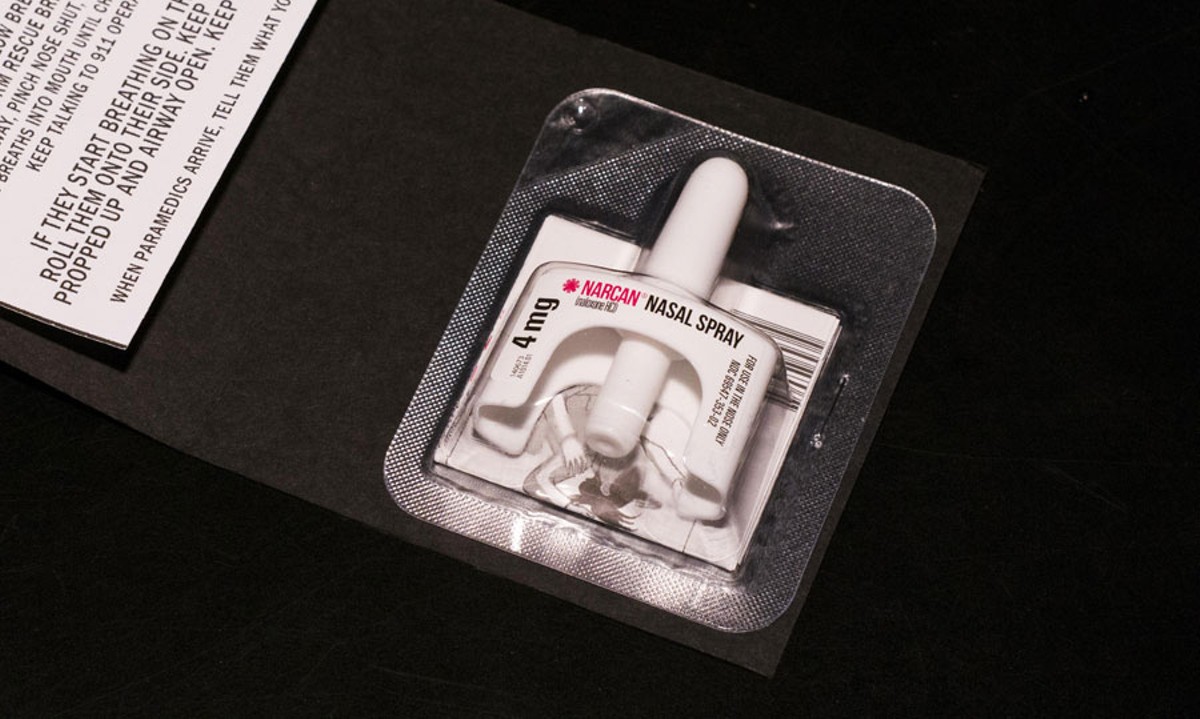

Last year, an unusual phenomenon began appearing in the news — that opioid users were hosting "Narcan parties" or "Lazarus parties," where users would binge on opioids until they overdosed, then be brought back with Narcan, the brand name for the overdose-reversing drug Naloxone.

WWMT West Michigan Channel 3 reported: "The Drug Enforcement Agency is warning police about a troubling trend popping up all across the country. Heroin addicts are having so-called 'Lazarus parties,' where police say they designate one person to stay sober and then revive anyone who overdoses with Naloxone." KSL Salt Lake City reported: "There is new concern that naloxone, the drug that counteracts an opiate overdose, could be used in what Utah's Drug Enforcement Administration is calling 'Narcan parties.'"

Given that both stories mentioned the Drug Enforcement Agency, we thought we'd check in with the federal law enforcement group and get the straight dope ... er, information right from them. And yet, according to Special Agent Cheryl Davis, the public information officer for the Detroit Field Divison of the DEA, "There have been no official statements released by DEA regarding 'Lazarus Parties,' 'Narcan Parties,' etc." Davis said that she "would not consider [the WWMT] story reliable," as it referenced no specific quotes. Davis also pointed out that the DEA "focuses on major drug traffickers and not individual users," making it an unlikely source for information on street-level use.

Frankly, we had already thought the story was hard enough to believe. Our first responder friends had told us many a tale about cracking drug boxes and administering Narcan before it was available at Walgreen's. The drug's reversal effect is as dramatic as it is unpleasant. After a shot of Naloxone, a person will go from a near-death state to bolting upright, sometimes projectile vomiting, and awakening into a panicked, often angry state. Full-blown addicts don't take heroin to get high so much as to feel normal, to avoid the torment of withdrawal. Naloxone catapults them immediately into that painful state, and it's only natural their first reaction is often to feel angry about the life-saving reversal.

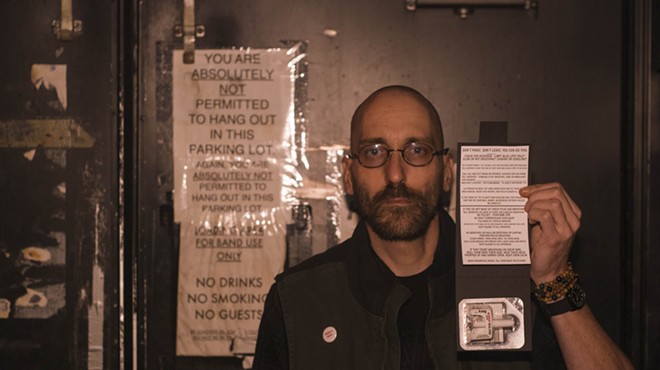

But, just to be sure, we decided to bring it up with a real social worker. Jason Schwartz has a 40-year career in social work, and is now clinical director at Washtenaw County-based Dawn Farm treatment center, which serves around 2,200 people a year, mostly for opioid addiction. We asked him in particular about a quote in Lansing's City Pulse from Sept. 21, 2017, which quoted Ingham County Sheriff Scott Wriggelsworth as saying, "They're called Lazarus parties, where they take heroin to the tune of almost dying and then they have Narcan there to bring their buddies back."

When he had finally stopped laughing, Schwartz said, "To me that is as likely as alligators living in the sewers of New York City. Stories like this pop up from time to time. One example that comes to mind is from years ago: 'Skittles Parties' where teenagers would grab prescriptions from their family's medicine cabinet, and dump the prescriptions into bowls at a party, and kids would go grab handfuls, not knowing what they were, and take them. That was just as absurd as this is."

"You do have people who OD and other users or family members are using Narcan to revive them," Schwartz says. "But the idea that there's some intentionality there, like, we're going to try to push it to the limit to the point where I OD, and you're here to revive me, that's silly."

So why would public officials share stories about alleged parties where the antidote is a part of ritual drug abuse? One useful clue is that proposed "Narcan cap" often featured in these articles. For instance, the Ingham County story had said, "experts say [Narcan] hasn't done anything to help curb the addiction crisis. In fact, it may even falsely reassure addicts that they can continue their risky behavior." The story quoted Sheriff Wriggelsworth as saying, "We've had multiple instances where three or four hours later, we're going back on the same person and administering Narcan again."

That same story mentioned Middletown, Ohio, reporting that Middletown spent $2 million responding to overdoses. (Actually, the $2 million figure includes costs ranging from addiction treatment to needle exchanges. The annual cost of providing the drug to the Middleton Fire Department is estimated at $90,000.)

The reason the Ohio city crops up so often is that a member of Middletown's city council proposed a cap on how often someone can be given Narcan. Middletown City Council member Dan Picard said, "I want to send a message to the world that you don't want to come to Middletown to overdose because someone might not come with Narcan and save your life. We need to put a fear about overdosing in Middletown."

The operative idea seems to be that when addicts are afraid of dying of an overdose, they are less likely to use drugs.

And yet that flies in the face of all actual research about opioid use. Fear of death doesn't stop people from using drugs. What stops people from using drugs, in the end, is treatment.

"The proper way to think about Narcan rescues is its like a defibrillator," health professional Schwartz says. "We have automatic defibrillators all over the place. The difference is that when people have a cardiac event and end up at the hospital, we have a full system of cardiac care they get engaged in. That is not the case with opioid addiction. People often end up getting released to nothing or an outpatient referral, and people need more care. That's why we end up with these cycles of people overdosing, getting rescued and getting released again. It's got less to do with the addicts and more to do with the system."

As Schwartz makes clear, pushing for treatment and understanding will do more good than irresponsible allegations of Narcan "parties" and talking about caps on life-saving drugs.

"Would you say the same thing about another chronic health problem?" Schwartz asks. "If you're talking about asthmatics or diabetics, would you put a cap on the number of rescues? It wouldn't be acceptable for any other health problem and its not acceptable for this one."

Schwartz adds, "The truth is, you deny them access to it and they'll die. Overdoses will stop but they'll stop not because they got sober but because they died. There are some people who, because of stigma, their attitude is, 'Let them die. We'd be better off without them.'"

"That may be an easy attitude to hold until the reality hits that this is your children, your uncle, your neighbor."