In a small resort town in northern Michigan, Kyle Knight is more than the police chief.

Having trouble finding a new officer for the short-staffed Harbor Springs Police Department, Knight, who is nearly 60 years old, is also working night shifts to patrol the streets so that the city of 1,285 residents has 24-hour police protection.

The constant double shifts can be gruesome, but Knight says he doesn’t have a choice.

“It becomes more of a challenge to cover the roads during the night shift and then still fulfill my administrative duties in the day,” Knight tells Metro Times.

With one of the highest crime rates in the country, Detroit was down 300 officers last year, prompting the city to launch an expensive and robust campaign to recruit and retain officers.

Detroit and Harbor Springs are far from alone. Michigan is in the midst of a severe police officer shortage, with departments big and small struggling to fill vacancies.

The number of police officers in Michigan has fallen from 23,000 in 2001 to 18,500 today, a 19.6% decline. In just the last three years, the state lost about 900 officers.

Without enough cops, departments are spending more on overtime and struggling to meet the demands of investigations and traffic patrols, creating serious concerns about public safety.

The staffing crisis has forced police departments into the uncomfortable position of contemplating lowering their applicant standards, a scenario that worries activists and law enforcement experts at a time when law enforcement is already under fire for high-profile incidents of misconduct. Some departments have eased restrictions on drug use, nepotism, residency and age requirements, and minimum education standards, while others have eliminated tests for physical ability and typing, according to a March 2022 survey from the Police Executive Research Forum.

What’s further concerning, experts say, is the pressure on departments to hire “wandering officers,” which are cops who hop from agency to agency after committing misconduct.

“Every agency is screaming for more police officer applicants and so that makes hiring and the acceptance of officers who may have questionable backgrounds a problem for us,” says Patrick Solar, a former police chief in Genoa, Illinois, and a criminal justice professor at the University of Wisconsin-Platteville. “To hire people to fill the ranks, we may intentionally or inadvertently lower our standards. It brings in the opportunity for officers who may run into trouble moving from one agency to the next.”

At his department, Knight says he wouldn’t be working double shifts if he was willing to lower his standards.

“Back in the day, if you had a misdemeanor arrest, you didn’t stand a chance because there were so many people in the application pool,” Knight says. “Now you can have a misdemeanor arrest and still get hired.”

But, Knight says, he’s not lowering his standards: “I will work every shift before I’ll hire someone who will compromise the reputation of our department.”

Losing interest in law enforcement

Law enforcement officials blame the police shortage on the COVID-19 pandemic, diminishing health care and pension benefits, and the stigma following the murder of George Floyd by a Minneapolis police officer in May 2020.

An unprecedented number of officers have retired or resigned since 2020, and departments are struggling to find replacements, police officials say.

“It’s a perfect storm,” Robert Stevenson, executive director of the Michigan Association of Chiefs of Police, tells Metro Times. “Many police officers are willing to potentially give up their life to protect their community, but they are not going to give up the financial security to put a roof over their family’s heads.”

Following the high-profile shootings of unarmed Black men over the past decade, many young people say they are turned off by a career in law enforcement. Stevenson says those cases paint a distorted picture of police officers.

“There are criminals wearing blue who do something like that, and it stains all of us,” Stevenson says. “It’s difficult to overcome. I remember when George Floyd was killed. I knew what was going to happen. We were trying to get over Ferguson,” in Missouri, where Michael Brown was killed by police in 2014.

Since Black men are often the victims, police departments are having an especially difficult time recruiting people of color.

“Who would want to join a profession where the stereotype is that you are not welcome?” Stevenson says. “It has really impacted recruitment and has hurt our diversity efforts.”

Ike McKinnon, a retired chief of the Detroit Police Department, says the best solution is boosting recruitment efforts and offering competitive salaries and benefits to attract good candidates. Hiring officers with a past record of egregious misconduct should never be an option, he says.

“One of the worst things any city or police department could do is lower their standards,” McKinnon tells Metro Times. “The last thing we want to do is allow officers with checkered pasts to jump from department to department. They will bring their problems to you.”

Detroit Police Commissioner Willie Burton agrees, saying it’s critical that departments maintain high standards by recruiting high-quality candidates.

“When you hire an officer who has a disciplinary history, you are inheriting that liability and that can cost any municipality dearly,” Burton tells Metro Times. “Instead, we should be investing in our youth. With an investment like this, it will inspire a child to consider joining law enforcement when they become an adult. These are cool jobs for the 21st century that pay really well. But our children have to have positive role models and good exposure to law enforcement.”

Burton says DPD must focus on recruiting young Detroiters, especially recent high school graduates, to fill vacancies, instead of taking a chance on an applicant with a problematic past.

“We should be in all of the high schools, exposing students to law enforcement and showing them the variety of jobs that are available,” Burton says. “If we recruit from within the city, we are more likely to have officers who respect residents and the job. We need to invest more into our youth before it’s too late.”

But advocates of reform say that hiring more officers is not necessarily the right answer. During the George Floyd protests in 2020, activists called for defunding traditional police. The idea was to fill less-risky police duties with civilians. Police departments across the country are experimenting with new forms of policing that would rely less on traditional police.

Wandering cops

The frequency of abusive cops jumping from department to department in Michigan is somewhat of a mystery because state police have declined to divulge records about officers and their employment histories. Metro Times and the Invisible Institute, a nonprofit news organization based in Chicago, filed a lawsuit against the state on Nov. 27 for declining a request for public records under the Freedom of Information Act.

State lawmakers tried to put an end to wandering cops in 2017 with a bill that required police departments to retain records that explain why an officer leaves. The law also requires officers to sign a waiver to allow other departments to view their previous records.

But it didn’t prevent officers with significant histories of misconduct or use of force from being hired again, and it didn’t stop agencies from allowing officers to resign, rather than be terminated. If an officer is allowed to resign, the documentation required to be kept about their separation is likely to be much less substantial.

While well-intended, the law hasn’t stopped cops from jumping from department to department after engaging in misconduct. Last year, the Eastpointe Police Department hired Kairy Roberts, an officer who resigned from the Detroit Police Department after an internal investigation found that he had punched an unarmed man in the face and then lied about it.

With so many open positions, law enforcement officials are worried that applicants with abusive histories will slip through the cracks.

tweet this

After a news story revealed the hiring in May, the Michigan Commission on Law Enforcement Standards (MCOLES) responded by suspending Roberts’s license, preventing him from serving as a cop in Michigan.

MCOLES keeps records of police officers’ identities and is tasked with certifying cops.

With so many open positions, law enforcement officials are worried that applicants with abusive histories will slip through the cracks and land a job.

At an MCOLES meeting in February, Mark Diaz, the director of recruiting and background checks for the Wayne County Sheriff’s Office, complained that police agencies aren’t filing separation reports, which identify details behind an officer leaving a department, in a timely fashion as required by the 2017 law. He said his department hired an officer after MCOLES’s tracking network showed no problems with the candidate, only to find out later that there was “a red flag.”

Ironically, Diaz himself has a criminal record. In October 2017, when he was president of the Detroit Police Officers Association, Diaz was convicted of a misdemeanor count of reckless driving after a dangerous joyride through the parking lot of the Holly Academy in Holly in December 2016. The pickup he was driving plowed through snow drifts and drove over the lawn, damaging a drainage culvert that cost the school $4,200 to repair. Tracks in the snow led police to his nearby home, where his pickup’s front end was damaged, with a portion of his bumper ripped off and found on school property.

Diaz, who was acquitted of a felony count of malicious destruction of property over $1,000, avoided jail and the loss of his police license, allowing him to land a job at the Wayne County Sheriff’s Office.

A Detroit Free Press investigation published in 2017 found that about two dozen problematic officers “jumped from department to department in recent years.” Some of them were fired and criminally charged, only to find work at another law enforcement agency. But since records of police officer names and disciplinary histories are kept secret, the problem is likely far worse than the Free Press found.

Offering incentives

In metro Detroit alone, there are hundreds of vacant police positions that departments are struggling to fill. The Wayne County Sheriff’s Office, for example, is short more than 200 employees.

Filling those vacancies has been difficult because of continuous news coverage of police abusing their power, which is discouraging many young people from pursuing a career in law enforcement, Sheriff Raphael Washington says. Instead of ignoring the issue, Washington appeals to young people’s desire to create change.

“You know what I say to them?” Washington tells Metro Times. “I say, ‘Listen, you have to be the change you want to see. Be the difference. Come on the inside and be the difference and be that change.’”

Like other departments, Washington’s office has stepped up recruitment, from holding job fairs to running ads on radio, television, billboards, and bus stops, and the county has increased wages for deputies. Over the next three years, deputies, detectives, and corporals will receive a 24% wage increase, which Washington calls “the biggest raises in the history of the county.”

The Wayne County Sheriff’s Office is also offering a $2,500 incentive for new employees and an additional $2,500 after their second year of employment.

The “robust recruitment campaign” is paying off, Washington says. At the beginning of the year, the sheriff’s office had roughly 350 job openings. It’s down to roughly 200 today.

To boost employment, Washington says it’s critical for law enforcement agencies to resist reducing hiring standards that are already low. To work at many police departments in Michigan, applicants only need to be 18 years old, have a high school diploma or GED, and not have a felony.

“Our standards have been lowered to the point where you can’t lower them anymore,” Washington says.

“We have people applying in record numbers,” Washington adds. “Not everyone qualifies. But they are trying to get in.”

The sheriff’s offices in Oakland and Macomb counties also have dozens of unfilled vacancies.

Instead of lowering its standards for the quality of applicants, the St. Clair Shores Police Department in Macomb County lifted its ban on beards and visible tattoos to address its vacancies. To address its vacancies, the St. Clair Shores Police Department in Macomb County lifted its ban on beards and visible tattoos.

“Our standards have been lowered to the point where you can’t lower them anymore,” Washington says.

tweet this

According to MCOLES’s standards, applicants can commit some misdemeanors and still become a cop. The exceptions are misdemeanors such as possession of drugs, aggravated assault, stalking, or a second offense of drunk driving or domestic violence.

Stevenson says the Michigan Association of Chiefs of Police is firmly opposed to reducing standards that would impact the quality of law enforcement.

“We can’t afford to lower our standards,” Stevenson says. “That is one of the things that departments are really pushing against. You’re better to run short than get someone with marginal character because the stakes are higher.”

In Memphis, where cops fatally beat Tyre Nichols during a traffic stop in January, the police department lowered its hiring standards in an effort to fill vacancies, leading to under-qualified and inexperienced officers within its ranks.

Jerry Rodriguez, a law enforcement expert who serves as an expert witness in police-related issues, says departments should not lower the bar to fill the ranks, and instead should focus on recruitment and providing a good working environment to attract and retain officers. He said it’s also important to resist rushing the hiring process so that adequate background checks can be done.

Part of the challenge, he said, is enrolling significantly more recruits into academies than there are positions to fill.

Because the academy has rigorous standards, many of the academy attendees either drop out or don’t perform well enough to land a job.

“I believe it would be detrimental to allow some people to get through the cracks because they become a problem later,” Rodriguez, of the JR Investigative and Consulting Group, tells Metro Times. “You have to make sure you bring in people with the desired traits you are looking for. It doesn’t behoove us to cut corners, even if you aren’t attracting enough people.”

Detroit makes progress

In September 2022, Detroit Mayor Mike Duggan said the city’s police department was scrambling to fill 300 unfilled positions.

Two months later, the Detroit City Council approved the largest pay increases ever given to the city’s police officers in an effort to attract new cops and retain current officers. The annual starting salary jumped from $43,000 to $53,000. By contrast, the starting salary for new officers was about $29,000 before the city filed for bankruptcy in 2013.

Officers with more than four years of experience received a $13,000 increase, pushing their annual salaries to $73,000. The annual salaries of detectives and lieutenants rose an average $11,000, while sergeants saw an average boost of $10,000 a year.

At a news conference at the time, Duggan said the pay increases will “completely transform the department’s ability to be fully staffed with the best police officers.”

With overtime, Detroit officers often make far more than their base salaries.

DPD also launched a secondary employment program that enables officers to work second jobs for extra money.

In May, eight months after the pay increases, DPD’s vacancies dropped from 300 to about 200. Today, the department has 65 vacancies, according to DPD.

Detroit is also increasingly spreading the word about police officer openings using billboards and social media, holding job fairs, and talking to high school and college students.

One of the most promising signs that DPD’s recruiting is working is that dozens of officers who left the department for the suburbs are returning.

“We’re getting them back from everywhere,” Detroit Police Sgt. Jordan Hall tells Metro Times.

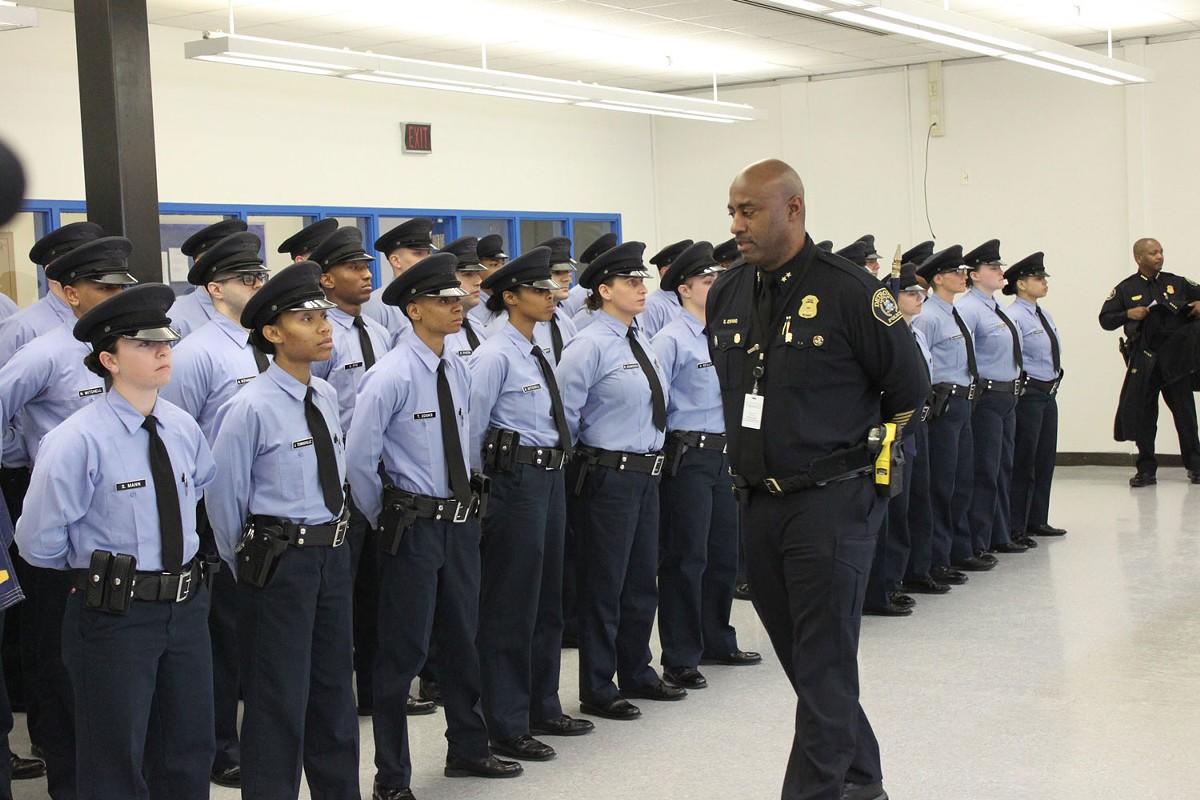

DPD has also focused on recruiting women and people of color. About a quarter of DPD’s officers are women, and more than half are Black, Hall says.

“We’re steadily hiring, and it’s going really well,” Hall says. “We’re trending in the right direction.”

Michigan lends a hand

The police shortage has caught the attention of Gov. Gretchen Whitmer and state lawmakers. In October 2022, Whitmer announced $30 million in grants to help departments pay for police academy recruits. For each recruit, a department can spend up to $24,000 to help cover the costs of training academies and recruit salaries.

“As a former prosecutor, public safety is a top priority, and I will work with anyone to ensure state and local law enforcement agencies have the resources, personnel, and training they need to keep our communities safe,” Whitmer said in a statement at the time. “After listening to law enforcement across the state, we are delivering $30 million in funding to help them hire additional officers. This funding is a critical component of our plan to boost investment in public safety across the state. Every Michigander deserves to feel safe while going to the grocery store, dropping their kids off to school, or taking a walk around the block.”

As of October, the state spent $13.8 million of the money, helping 199 agencies assist 615 recruits, according to MCOLES executive director Timothy Bourgeois.

In the past, prospective police officers often paid their own tuition to attend the academy, which typically ranges from $6,000 to $10,000, according to a Senate Fiscal Agency analysis. By providing departments with the money to cover the costs of tuition, police departments are having better success at attracting recruits, Bourgeois says.

“The Public Safety Academy Assistance Grant Program has been very beneficial to law enforcement agencies,” Bourgeois tells Metro Times. “It has enabled them to hire individuals to send to the academy as an employed recruit, and in many cases, the local municipalities lacked the resources.”

In addition to helping pay for recruits’ academy costs, DPD provides attendees a $46,800 salary with health benefits.

The state is also trying to recruit officers from outside of Michigan. With $2.7 million set aside in 2022, the state is offering to pay for the certification of officers who relocate to Michigan.

Other states are offering similar incentives for relocations.

In December 2021, the state House passed a bill that would have set aside $57.2 million to encourage out-of-state officers to move to Michigan. The bill was later shelved by the Senate.

In September 2022, Republican gubernatorial candidate Tudor Dixon proposed a whopping $700 million measure to recruit and retain police officers, firefighters, and public safety personnel. The proposal died with her failed campaign.

However, some experts have warned that such recruitment tools could backfire.

“As a business decision, hiring former officers can offer benefits for any police department,” wrote Dorothy Moses Schulz, a former transit police captain in New York who is also a professor emerita at the John Jay College of Criminal Justice, in a 2022 report published by the conservative Manhattan Institute. “But these departments must consider the possibility that they are attracting officers who are running away from problems.”

“I’m concerned about these incentives overall,” she said in an interview. “You’re recruiting from the same pool. This one’s offering $5,000, this one's offering $7,000.

“But all these smack to me of desperation. And I think it’s very sad that we’ve come to a point where police have to be desperate to recruit.”

Poaching police officers

Paying for recruits’ tuition had unintended consequences in Detroit. New officers were often leaving for other departments after the city paid for their tuition. DPD officials said departments from as far away as Toledo and Houston were showing up at the Detroit Police Department Academy to lure recent graduates.

In 2022 alone, more than 100 officers left DPD for other departments. To discourage this trend, Whitmer in June signed legislation, which has been coined the “poacher bill,” that required recruits to pay back 100% of their academy training costs if they leave DPD within one year of graduation. The amount decreases every year by 25%, allowing Detroit to recover a portion of its academy costs up to four years after recruits graduate.

“We have experienced over the last several years a large number of individuals joining the Detroit Police Department for the training with an apparent plan to leave for suburban police departments shortly thereafter,” DPD assistant chief David LeValley said during a legislative hearing before the law was passed.

“I’ve been told that some agencies have actually encouraged individuals to do so,” LeValley added. “And we have even had police chiefs and command staff from suburban police departments attend our academy graduations only to have a recruit resign the next day and go work for that agency.”

Detroit offers its own training academy at a cost of about $35,000 per attendee.

In June, the cash-strapped city estimated that it had spent nearly $6.4 million to cover the costs of recruiting, training, and hiring police officers who left the department after fewer than four years of service since 2020.

“For too long, police recruits knew they could receive the best training available at DPD, and then take that training to a suburban department that paid them more,” Duggan said in a statement at the time.

Despite making strides forward, many police departments are still far from fully staffing their ranks.

“Departments are offering bonuses and lateral transfers to get people into their department,” Stevenson, of the Michigan Association of Chiefs of Police, says. “But all we’re doing is stealing from each other. To some degree, we’re playing whack a mole. The actual number of police officers isn’t going up.”

Times have changed since Stevenson began his career.

“When I applied to be a cadet in Livonia back in the 1970s, there were 750 candidates with six positions,” Stevenson says. “Now I routinely hear that a department gets one candidate. And a lot of them don’t have the character or fitness to become a police officer.”

Knight, chief of the Harbor Springs Police Department, offered a dose of optimism.

“Law enforcement is coming back,” he says. “I don’t know if it will ever get back to what it was 30 years ago. Sooner or later, there will be a positive twist. It’s a problem right now more than it ever has been, but I think we’ll come out of it.”

Experts say the solution to the police staffing crisis may require a new vision for public safety. One alternative that reform advocates have called for is using civilians to do jobs previously done by sworn personnel.

Jeffrey B. Welty, an expert in criminal law and procedure at the University of North Carolina, said hiring sworn personnel “is arduous, time-consuming and expensive” because of the training costs and the significant testing requirements, he wrote in October 2022.

Increasingly, departments across the country are relying more on civilians to perform administrative functions in police departments. Those positions include public information officer, evidence technician, property management specialist, crime scene investigator, forensic analyst, victim advocate, and data analyst.

Other departments are going further. For example, Berkeley, Calif., is hiring civilians to conduct traffic enforcement. Baltimore is hiring “civilian investigative specialists” to work in the police department’s detective units. Their role is working with sworn officers on cold cases, internal affairs issues, and property crimes. In Denver, mental health experts and paramedics are responding to certain 911 calls.

In April 2021, the Ann Arbor City Council voted to create an unarmed crisis response program to support alternatives to policing. Inspired by Ann Arbor, University of Michigan officials are exploring the creation of an unarmed crisis response team to respond to calls for help on campus.

In a letter to UM President Santa Ono in August, seven advocacy groups urged him to support the creation of the unarmed crisis response team, saying many people distrust interactions with armed police.

“Community members who live, work, learn, and play on campus deserve access to an option for calling for support in times of conflict, crisis, and concern for wellbeing without involving armed officers who are trained for law enforcement rather than providing care,” the letter states. “In a country where people of color, mentally ill and mad people, transgender people, and poor people are disproportionately met with prejudice and force, an alternative option is especially important. Many people on campus who are experiencing a crisis must weigh the benefits of calling for help with the risk of discrimination, violence, punishment, or being coerced into ‘treatment.’ These conditions lead many members of our community to avoid asking for help because the risks outweigh the benefits of the response they will currently receive. We find this unacceptable and unjust.”

In August, Ono agreed to support the unarmed response teams.

The Police Executive Research Forum wrote in 2019 that “police agencies in the future may rely more heavily on civilian staff, contract services, and community partnerships than on full-time sworn staff. … It is important for the policing profession to be flexible and open-minded about changes that will help police agencies to serve their communities in new ways.”

Invisible Institute journalist Sam Stecklow contributed to this report.

Subscribe to Metro Times newsletters.

Follow us: Google News | NewsBreak | Reddit | Instagram | Facebook | Twitter