Just making it through the winter of 2014 could mark a major victory for the members of the New Work Field Street Collective. The group, now numbering about 10 members — six of whom live together in the house on the corner of Field and Vernor streets — moved into the three-floor, 17-room edifice on Aug. 1. At that time, the house didn’t have pipes or wiring, or a furnace.

“We had been in survival mode there — not trying to develop,” says member Blair Anderson. “Just to get through a very harsh winter for us under challenging circumstances.”

The house had formerly been vacant. The owner had gone through financial issues with the bank and was out of it for a while. During that homeowner’s sojourn away from the house, urban miners stripped all the metal out of the place. The owner came home to an unlivable house.

At a neighborhood meeting, some Field Street Collective members spoke about looking for a place in the neighborhood. The home’s owner had one.

“It was like a magical moment,” says Peggy Hong, another collective member.

It was at least a convergent moment for the owner, who now lives on the third floor, and the Field Street Collective (FSC) members, who inhabit the first and second floors. Members of the FSC had been active in the neighborhood around issues such as home foreclosure and gardening. Hong — who had come to town about a year ago to cook for Grace Lee Boggs — and other collective members were looking for a space to establish a project based on New Work principles. Hong and Anderson participate in a New Work discussion group at the Boggs Center with, among others, retired U-M philosophy professor Frithjoff Bergmann, who developed the principles around 1980.

In short, New Work says that, due to technology, we are going through a major change in the way we work. We’ve already seen examples of that in the shrinking of the workforce and higher unemployment. The greater vision is building a culture around community production, made possible by the 3-D printer and other technologies. Instead of requiring giant factories, many things can be produced in small rooms inside a community. This new world will not only create new kinds of jobs, but our relationship to them will be different. One of the changes would be that people work for pay about a third of their waking hours, another third would be doing personally uplifting work (possibly creative in some way), and the other third would involve work that aids the community, such as working in the garden. There’s more to it.

“We’re trying to apply New Work principles every step of the way,” Hong says. “At the same time, we’re taking liberties with the New Work philosophy in how we apply it. Most New Work communities begin with investors; some have investors with deep pockets. We do have backers but, even so, we didn’t have any major investors. Our project is really slower than many Frithjoff is working with because we don’t have major investors.”

Bergmann is involved with projects as far off as South Africa and Austria. A recent project in Europe built an electric motorcycle with parts made in 3-D printers.

In Detroit, the project reflects the situation here. The collective got the house wired up, got the water running, and bought a new furnace through the help of small donations and loans from community members.

“The house basically took up all of our time and energy this fall,” Hong says. “Now I think we can apply ourselves more earnestly to New Work projects. Up till now it’s been kind of just creating the stability in terms of our living environment. We’re just now getting enterprises off the ground. The house took up much more time and energy than any of us anticipated.”

The businesses incubating there right now include New Work Leather, which makes bags, wallets, belts and more; Homespun Hustle, which uses sewing, knitting and fiber work to produce articles of clothing; Healing House, which offers yoga, massage, meditation, capoeira and food-as-medicine practice and classes; and Food2Gather, an ongoing series of donation-based community meals. All of the enterprises are run by qualified individuals. The massage program has a licensed masseur. Hong ran a nonprofit yoga studio in Milwaukee for 25 years.

This month, Milwaukee-based quilter Rosy Ricks is artist-in-residence with the collective. Her goal for the month is to complete five quilts. One is a gift to the household. The others are offered through Homespun Hustle.

They’re getting help with planning from Lisa Stolarski, a community economic development consultant who specializes in cooperative business planning. She works at Church of the Messiah and participates in the New Work discussion group.

“I can see their productivity being greatly increased with a little bit of awareness of what their capacity is for production and marketing,” Stolarski says. “They’ll be able to make a great improvement in the profitability of their micro-enterprises. … It’s unusual in that it’s a group of people who are thinking about more than one aspect of their economic sustainability together. Usually people share in only one aspect of econ sustainability, such as a cooperative house or a cooperative business. We have these partnerships throughout our lives. With New Work they’re being intentional about those relationships. Most people don’t even know the people they share their retirement fund with.”

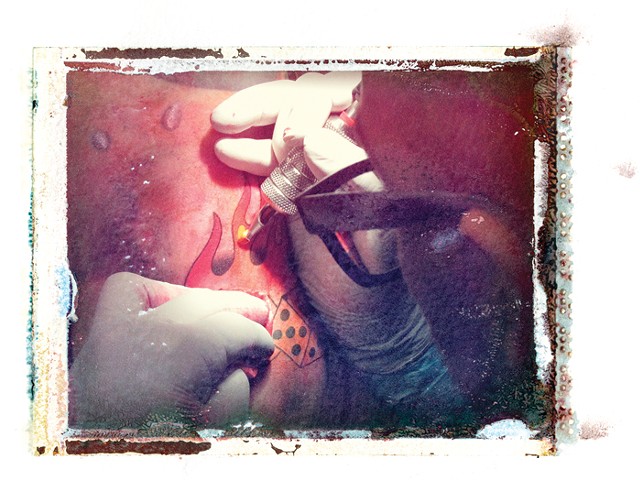

Collective member Anderson isn’t a resident of the house; he lives with his wife elsewhere. He’s trying to re-establish himself in the community after 23 years in prison for robbery. While incarcerated, he learned leather craft and made money making belts and other things. Now he’s using those skills for the betterment of the community. Not only has he established New Work Leather, he’s teaching youth how to do it as part of the project.

“I’ve trained two people to do leather craft,” he says. “[I] anticipate that when we can purchase more tools and supplies there are two people from the community who want to train with us.”

There is also a retired neighbor who wants to start a landscaping business, not so much to make a profit but to create work for youth in the neighborhood. That’s part of the whole idea, basing enterprises in the neighborhood and having buy-in from the neighbors. Collective members and others expect to have a community garden soon, and they’re working on a renewable-energy project using biomass to generate electricity.

It’s a very down-to-earth response to something that can seem very abstract and beyond your grasp. Talking about the end of work as we know it and new paradigms sometimes doesn’t speak to you where you live. Community gardens, quilts and belts are something you can get your arms and head around.

It can be very basic. Like the way the Field Street residence took shape. “There was a space,” says Anderson. “We had a need and a vision.”

New Work Field Street Collective can be contacted through the group’s Facebook page.