Audio By Carbonatix

[

{

"name": "GPT - Leaderboard - Inline - Content",

"component": "35519556",

"insertPoint": "5th",

"startingPoint": "3",

"requiredCountToDisplay": "3",

"maxInsertions": 100,

"adList": [

{

"adPreset": "LeaderboardInline"

}

]

}

]

An ongoing series about extremism and the radicalization of the Michigan Republican Party

• Part 1: How a Michigan couple radicalized the state’s GOP and emboldened insurrectionists• Part 2: White angst keeps Trumpism alive in Macomb County

• Part 3: Behind the GOP plot to restrict voting access in Michigan

• Part 4: Michigan Republicans clash over Trump’s future in the party

In the months leading up to the general election in November 2020, local clerks and state officials took unprecedented steps to expand voter access in the midst of a deadly pandemic.

Like in many other states, election supervisors in Michigan sent absentee ballot applications to all active registered voters, supplied prepaid postage on election mail, and provided more than 1,125 drop boxes at curbside locations across the state. The idea was to offer a safe alternative to voting in person.

By almost any measure, the election was considered a resounding success.

A record 5.6 million Michigan voters cast a ballot in the general election, shattering the previous record of 5 million in 2008. Of those ballots, 3.3 million were absentee, a three-fold increase from the November 2016 election.

“Due in no small part to these policies, we had the most successful, secure election in our state’s history,” Michigan Secretary of State Jocelyn Benson told the U.S. Senate Committee on Rules and Administration during a hearing on election reform on March 24. “Voter participation — on both sides of the aisle — skyrocketed.”

But that success was quickly besmirched by then-President Donald Trump and his ardent supporters, who repeatedly claimed, without evidence, that the election in Michigan and other battleground states was mired in widespread fraud.

Instead of trying to replicate the practices that made the election so successful, Republicans are trying to dismantle them. Under the guise of “voter integrity,” GOP lawmakers in Michigan have introduced a 39-bill package that would curtail voting access, impose restrictions on absentee ballots, limit the secretary of state’s ability to assist voters, and make it easier for political appointees to overturn elections.

Voting rights advocates denounced the bills as a coordinated, nationwide voter-suppression campaign in the wake of the 2020 election. The legislation, they say, amounts to a new version of Jim Crow and would disproportionately harm voters of color.

“There was a record turnout of Black and Brown voters, and that is being met by a coordinated attack,” Merissa Kovach, policy strategist for the ACLU of Michigan, tells Metro Times. “Every moment in United States history, when there has been a major expansion of democracy, democratic action, and increase in voting, it has been met with voter suppression.”

The stakes are high. Since Michigan is a battleground state where races are often decided by a few percentage points, the bills could affect the outcome of future elections.

Republicans are hoping to enact the legislation by the 2022 general election, which includes races for governor, attorney general, secretary of state, and key congressional seats that could influence which party controls the U.S. House.

Misinformation campaign

Before voters even cast a ballot last year, Trump began to spread misinformation and sow doubt about the security of the election. He initially insisted mail-in ballots would lead to systemic fraud.

“This will be a fraud like you have never seen,” Trump declared during a debate in September.

As soon as the polls closed in November, the baseless claims and conspiracy theories picked up steam. While election workers counted ballots in Detroit, Trump supporters falsely claimed tens of thousands of fraudulent ballots were smuggled into the TCF Center hours after the polls closed.

Trump repeatedly alleged that Detroit received more votes than there are residents, an easily refutable claim.

“In Detroit, there are FAR MORE VOTES THAN PEOPLE,” Trump tweeted on Nov. 18. “Nothing can be done to cure this giant scam. I win Michigan!”

Truth is, about half of the city’s registered voters — 250,000 in a city of 670,000 residents — cast a ballot in the election.

The highest turnouts in the state were in rural communities that overwhelmingly voted for Trump.

In Antrim County, where Trump handily won, the former president’s supporters falsely claimed that Dominion Voting Systems tabulators were rigged to switch Trump’s votes to Joe Biden. The conspiracy theory led to a lawsuit that sought an audit of the county’s result. A judge dismissed the suit in May, saying the case was moot because the Michigan Secretary of State’s office properly concluded in March that the election was fair and accurate following a statewide audit.

Judges tossed out similar lawsuits that sought recounts, “special master” reviews, and in one case, a suit that sought to void the election altogether.

Biden won Michigan by more than 154,000 votes. By comparison, Trump won his first term in Michigan in 2016 by just 10,704 votes, a 0.23% margin.

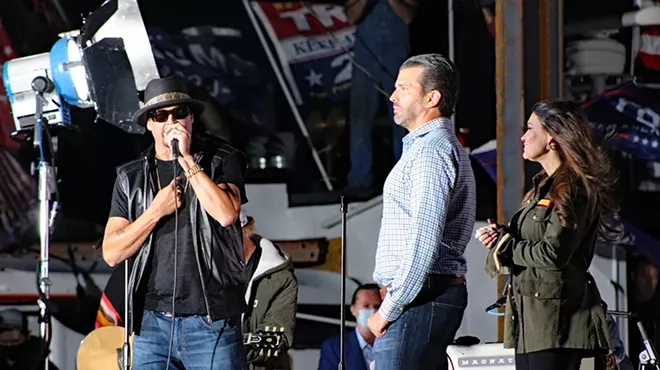

For two months after the election last November, Trump supporters held more than a dozen Stop the Steal rallies throughout the state, peddling falsehoods and wild conspiracy theories. Michigan Republicans even held their own caucus with an alternate slate of delegates to “certify” the election for Trump.

In the state Legislature, Republicans made several attempts to overturn the election, citing unfounded claims. A day before the deadly Jan. 6 insurrection, 11 Republican lawmakers in Michigan urged Vice President Mike Pence in a last-minute letter to delay certifying the electoral votes to give them more time to build a case for Trump.

Meanwhile, Trump’s own attorney general, FBI director, and Homeland Security department said there was no evidence of widespread fraud.

The state’s only known case of voter fraud was a Canton Township man who forged his daughter’s signature — with her permission — on an absentee ballot. The clerk’s office eventually accepted the ballot after contacting the daughter and obtaining her signature. He was sentenced to probation after pleading guilty to misdemeanor election law.

‘Egregious voter suppression’

Although Republicans failed to show any evidence of widespread fraud or irregularities, the deluge of accusations from GOP leaders, right-wing media, and elected officials was so rampant that many Trump voters still believe Biden did not legitimately win the election. In three separate polls earlier this year, more than half of Republican voters blamed Trump’s loss on widespread fraud.

Aligning themselves with Trump’s false claims that lax voting rules undermined the integrity of the election, GOP lawmakers in Michigan and more than three dozen other states have pushed for legislation to make it harder to vote.

In March, Michigan Senate Republicans introduced a 39-bill package that voting experts say is among the most restrictive in the nation and would disproportionately impact voters of color and residents in Democratic strongholds.

“This package of bills contains some of the most egregious voter suppression ideas Michigan has seen,” Chris Swope, president of the Michigan Association of Municipal Clerks, said. “With nearly 30% of Michiganders not participating, we need to focus on expanding ballot access, not attempts to disenfranchise certain voters.”

The bills take aim at what made the 2020 election so successful — absentee voting. Of the total ballots cast in Michigan in November, about 57% were mailed in or placed in a drop box, three times the rate in 2016.

Democrats also were far more likely to vote by absentee. In the six most populous counties in Michigan, more than 70% of the total votes cast by Democrats were absentee, compared to roughly 50% by Republicans, according to a Metro Times analysis of voting data.

One of the bills would bar the state from sending out unsolicited absentee ballot applications, as was done in November. Clerks also would be prevented from providing prepaid postage on absentee ballot return envelopes. And to return an absentee ballot by mail or a drop box, voters would be required to attach a photocopy of their driver’s license or state ID cards, one of the strictest proposals in the nation.

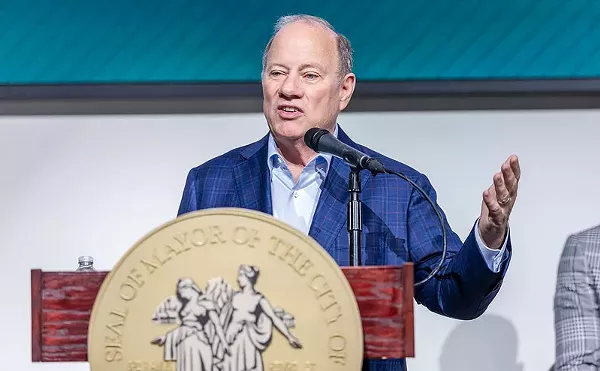

“Who has a Xerox machine around their house to be able to copy their ID?” Detroit Mayor Mike Duggan asked at a rally in Lansing in April. “The people who have those kinds of printers are not the people of lower incomes. This is done for one reason and one reason only — to raise the barrier for people of color and people of lower income to vote.”

At the rally, the Rev. Wendell Anthony, president of the Detroit branch of the NAACP, called the legislation “a grand scheme to suppress the rights of a select group of Michiganders.”

“We've lost too much blood, we've sweated too many tears, we've cried too many nights, for them to do this in the bright of day," Anthony said.

Another bill would forbid the secretary of state from posting a link on the state’s website to request an absentee ballot.

Taken together, the bills would weaken key parts of a voter-approved constitutional amendment in 2018 that allowed no-excuse absentee voting and expanded other voting rights in Michigan. The amendment passed in 80 of the state’s 83 counties.

“When you look at the impact of this package as a whole, the bills would impose significant burdens and make it more difficult for every single registered voter to cast a ballot and exercise their right to vote,” Sharon Dolente, senior adviser of Promote the Vote, the group that championed the constitutional amendment, tells Metro Times. “In 2018, Michigan voters desperately wanted to vote absentee and expand voting access. Now the Legislature is doing the opposite — pursuing a bunch of restrictions that people don’t want.”

The GOP bills also would limit access to drop boxes, despite no evidence of fraud. In last year’s election, more than 1,125 drop boxes were available statewide, offering voters a convenient and safe alternative to waiting in long lines at congested polling locations. Lines tend to be longer in bigger cities, where Democrats outnumber Republicans.

The legislation also would prohibit voters from using drop boxes on the day of the election.

“The majority of ballots returned through drop boxes in 2020 were dropped off on Election Day, particularly in the city of Detroit, where there were a few dozen secure drop boxes [utilized] heavily by citizens,” Benson said. “There is no data to suggest that banning the use of drop boxes will do anything other than disenfranchise citizens in the city of Detroit and all across the state who rely on drop boxes to return those ballots safely and securely by 8 p.m. on Election Day.”

“In 2018, Michigan voters desperately wanted to vote absentee and expand voting access. Now the Legislature is doing the opposite — pursuing a bunch of restrictions that people don’t want.”

tweet this

In Detroit, where 79% of the population is Black, only 5.1% of voters cast a ballot for Trump in 2020, one of the lowest rates in the nation.

One of the bills could nix the use of drop boxes altogether, putting the decision in the hands of county boards of canvassers. The boards, which are evenly split between Republicans and Democrats, would need a supermajority to approve the drop boxes.

“What do you think the chances are that there will be any drop boxes in the city of Detroit?” Duggan asked at the rally.

Drop boxes were most popular in bigger cities that are Democratic strongholds. Detroit offered at least 32 drop boxes, while Lansing had 17 and Flint had 12. Pontiac and Grand Rapids each had seven.

Even clerks oppose the bills

Voting rights advocates say the bills also make it more difficult for election officials to do their jobs. Some of the bills, for example, remove clerks’ funding sources while adding to their responsibilities.

Under one measure, election officials would be required to monitor all drop boxes with high-definition video cameras and follow new reporting requirements to document ballot collections.

The GOP package also authorizes state lawmakers to withhold federal election funds and bans clerks from accepting private funding.

Clerks have long complained that the GOP-controlled Legislature doesn’t adequately fund elections. In just the past year, clerks have received millions of dollars in private grant funding to pay for election-related expenses, such as personal protective equipment for workers and security cameras for drop boxes.

The Center for Tech and Civic Life, a nonprofit funded by Facebook CEO Mark Zuckerberg, provided grants to more than 450 Michigan communities last year to handle extra precautions during the COVID-19 pandemic.

“That funding was critical to use to make democracy work at a time when our state and federal government wouldn’t step up to the plate,” Benson said at a news conference. “If the state government doesn’t like that, they should fully fund our elections. We would welcome that.”

Numerous local clerks from both sides of the aisle have voiced opposition to the bills, saying they were never consulted by the authors of the legislation.

“The bills in this package show no trace of the expertise, insight, and data that have been shared with legislators in good faith by election administrators on both sides of the aisle,” Ingham County Clerk Barb Byrum said. “Sensible improvements to our election processes are needed, but those reforms should make our elections more inclusive, more efficient, and more secure. Instead, these bills amount to a willful, malicious attempt to strip voting rights away from Michigan's citizens."

Overturning elections

Election rights advocates warn that Republicans are trying to make it easier to block the certification of election results. The legislation targets four-member canvassing boards, which are tasked with certifying election results. They are evenly split between Republicans and Democrats, who are appointed by state parties.

One bill would increase the size of canvassing boards in the nine most populous counties — seven of which favored Biden — and make it easier for politically appointed members to deny certification. In counties with between 200,000 and 750,000 residents, the boards would have six canvassers, and five of them would have to certify the election. Those counties are Kent, Genesee, Washthenaw, Ingham, Ottawa, and Kalamazoo.

In counties with more than 750,000 residents, the boards would have eight canvassers, and six of them would have to certify the election. Those counties are Wayne, Oakland, and Macomb.

In both cases, at least two Republicans and two Democrats must vote to certify the election. Under the current law, certification only requires a yes vote from one canvasser from each party.

Following Trump’s loss, Republicans attempted to block the certification of election results in Michigan and several other battleground states. The two Republicans on the Wayne County Board of Canvassers initially voted against certifying, citing out-of-balance poll books. After the initial deadlock, the Republicans supported certification but later tried to undo their decision.

The legislation also imposes new stringent rules that would increase the chances that an election won’t be certified. Under one bill, counties must stop voting and report the results by noon on the day after the election, which Benson said creates “a legal impossibility for clerks who have no authority under law not to count all valid ballots.”

Another bill would forbid canvassers from certifying an election if more than 5% of precincts are “out of balance,” which happens when the total number of ballots tabulated doesn’t match the total number of voters who were issued a ballot.

If that bill were enacted before the 2020 presidential election, all of the votes in Wayne, Macomb, and Oakland counties would have been invalidated because more than 5% of the precincts were not balanced.

Election experts say out-of-balance precincts are not evidence of fraud. They’re the result of human error and are relatively common. The mistakes often happen when a poll worker forgets to record a ballot that is fed into a scanning machine.

Most out-of-balance precincts in Wayne County, for example, were off by just one vote, data shows. But if Wayne County’s votes were invalidated, Trump would have won Michigan.

“It’s very clear that the legislators who drafted these bills want to restrict the voting rights of the people of Detroit and other similar communities,” Detroit Clerk Janice Winfrey said at a recent news conference. “We are not going to stand for it. We fought too hard — we worked too hard — to ensure access to the ballot.”

Overriding a veto

Gov. Gretchen Whitmer has pledged to veto any bills imposing new voting restrictions. But Republicans plan to take advantage of a peculiarity in Michigan’s constitution that allows the state Legislature to circumvent a veto using a voter-driven ballot initiative. If more than 340,000 voters — or at least 8% of the total number of votes cast in the last gubernatorial election — sign a petition to create a ballot initiative on the restrictions, Republican legislators can bypass Whitmer and approve the law.

“If it’s not signed by the governor, then we have other plans to make sure it becomes law before 2022,” said Michigan GOP Chairman Ron Weiser at an event for the North Oakland Republican Club in March. “That plan includes taking that legislation and getting the signatures necessary for a legislative initiative so it can become law without Gretchen Whitmer’s signature.”

At the same event, Weiser called Michigan’s three female Democratic leaders “witches” to be burned “at the stake.”

Republicans are moving aggressively to enact the legislation ahead of the 2022 elections, which include races for governor, attorney general, secretary of state, and key congressional seats that could help determine which party controls the U.S. House of Representatives.

Voting rights advocates are preparing for a fight over the bills.

“We’re not waiting for the Democratic Party to handle this,” Branden Snyder, executive director of Detroit Action, a grassroots group that fights for racial, housing, and economic justice, tells Metro Times. “Groups like ours are going to make sure we take to the streets and let our conservative friends know that making it harder to vote based on racist lies won’t be tolerated. We need to make sure this isn’t happening under the cover of darkness.”

Snyder says Republicans are trying to scare voters into supporting the legislation by peddling misinformation and conspiracy theories. One of the common narratives, for example, is that voters are getting away with fraud because they can vote without an ID.

In Michigan, voters who don’t have a photo ID can sign an affidavit attesting to their identity under the penalty of perjury. More than 18,500 Michiganders voted by affidavit in 2016, when the election was decided by fewer than 11,000 votes. In 2020, about 11,400 people who voted in person signed an affidavit. The number of voters who don’t have access to their ID is likely much higher because current law doesn’t require absentee voters to show their ID.

But that could soon change. One of the bills calls for banning the use of a sworn affidavit and requiring voters without an ID to cast a provisional ballot that would only be counted if the voter provides more documentation to prove their identity. The new requirement would disproportionately impact voters of color, according to activists and researchers.

A quarter of the Michiganders who signed an affidavit live in Detroit, which represents less than 7% of the state’s population. Harvard University researchers last year examined Michigan voters who didn’t have an ID to vote and found that most of them possessed photo identification but didn’t have access to it during the election.

“Nearly all these voters were previously issued a still-active state ID,” the researchers wrote. “Importantly, we also find evidence of a disparate racial impact, with non-white voters about five times more likely to lack access to ID than white voters.”

Republicans depict the bills as commonsense safeguards against voter fraud and focus their rhetoric on photo ID requirements, all but ignoring the other restrictions.

"When half of Michigan’s voters don’t have confidence in the integrity of our elections, doing nothing is not an option,” Michigan GOP Chairman Ron Weiser said in a statement. “Election results should not be controversial and the unilateral changes to our elections by Secretary Benson have undermined the confidence our democracy requires. With 72% of Michiganders supportive of voter ID, we are on the right side of this issue and applaud the Republican Senate on their efforts to restore voter confidence."

Voting rights advocates have their work cut out for them. Heavily funded conservative groups plan to spend a lot of money supporting the voter restriction bills.

The conservative group Heritage Action for America, for example, plans to spend at least $10 million promoting restrictive voting laws in Michigan and seven other swing states.

Also leading the push nationwide are the American Legislative Exchange Council, a right-wing corporate lobbying group, and the Koch-funded advocacy nonprofit Americans for Prosperity. Both groups have crafted election-law changes and disseminated them to GOP leadership in Republican-majority states.

It’s one reason that dozens of states are pushing the same bills with nearly identical language.

“What’s happening behind the scenes is that Michigan legislators are participating in a national, coordinated, and highly partisan attempt to change the rules of democracy and make it harder for people to vote because they are unhappy with the result of the last year’s election,” Benson said, adding that the legislation is “nearly identical” to bills in Florida, Iowa, Texas, Florida, Montana, Arkansas, and Georgia.

The bills are so extreme that even corporate leaders across the country are fighting back. The leaders of three dozen major Michigan-based companies have embarked on a public press campaign to denounce the voting restrictions. In April, the companies, which include General Motors, Ford, Blue Cross Blue Shield, Quicken Loans, and all four Detroit professional sports teams, issued a joint statement opposing the legislation.

"We represent Michigan’s largest companies, many of which operate on a national basis," the statement said. "We feel a responsibility to add our voice as changes are proposed to voting laws in Michigan and other states."

Legislation is ‘un-American’

Democrats and voting rights advocates had pinned their hopes on federal voting legislation aimed at overriding many of the laws being passed in GOP-controlled states. The U.S. Senate’s For the People Act would have ushered in new national mandates to protect voters from the restrictive state laws. But the bill fell apart earlier this month when Democratic Sen. Joe Manchin III, of West Virginia, said he wouldn’t sign the legislation, saying it has become “overtly politicized.” Without GOP support, the bill needed the support of all 50 Democrats in the Senate.

“I believe that partisan voting legislation will destroy the already weakening binds of our democracy, and for that reason, I will vote against the For the People Act,” Manchin said in an op-ed in the Charleston Gazette-Mail.

In a statement last month, Biden said he supported the bill and condemned state measures as “part of an assault on democracy that we’ve seen far too often this year — and often disproportionately targeting Black and Brown Americans.”

“It’s wrong and un-American. In the 21st century, we should be making it easier — not harder — for every eligible voter to vote,” Biden said.

The final hope on the federal level may rest with the U.S. Department of Justice. Attorney General Merrick Garland unveiled a plan last week to scrutinize new state laws that restrict voter access to determine if they discriminate against non-white voters.

“Many of the justifications proffered in support of these post-election audits and restrictions on voting have relied on assertions of material vote fraud in the 2020 election that have been refuted by law enforcement and intelligence agencies of both this administration and the previous one, as well as by every court — federal and state — that has considered them,” Garland said in an address to the Justice Department. “Moreover, many of the changes are not even calibrated to address the kinds of voter fraud that are alleged as their justification.”

On the local level, voting rights advocates are digging in for a battle.

“We fought for the 15th amendment that gave the right to vote to Black people, the 19th amendment that gave the right to vote to women, the 24th amendment that eliminated the poll tax, the 26th amendment that dropped the voting age to 18. And here we are in 2021 in the midst of a pandemic still having to fight,” said Rev. Steve Bland Jr., president of the Council of Baptist Pastors of Detroit & Vicinity.

Stay connected with Detroit Metro Times. Subscribe to our newsletters, and follow us on Google News, Apple News, Twitter, Facebook, Instagram, or Reddit.