In his riveting memoir The Hard Stuff, guitarist Wayne Kramer cites the deaths of Rob Tyner, Michael Davis, and Fred Smith, his fellow musicians in Detroit’s legendary rock band, the MC5.

Tyner was the lead singer. Reflecting on his 1991 death, Kramer writes: “I never thought about Rob or any of the MC5 guys dying, just like I’d never thought about my own death.”

Kramer died at age 75 last week in Los Angeles of pancreatic cancer, more than 50 years after his “Motor City Five” musical group tried to reform — can you dig it? — the culture of the city of Detroit, the state of Michigan, the United States of America, the whole planet, and the entire universe, brothers and sisters, with loud, hard-core, revolutionary rock music, radical politics, free love and mind-altering drugs, man. Power to the people!

“I embraced many of the most extreme ideas and actions of my day,” Kramer wrote. “It was both frightening and exciting … I was a romantic anarchist.”

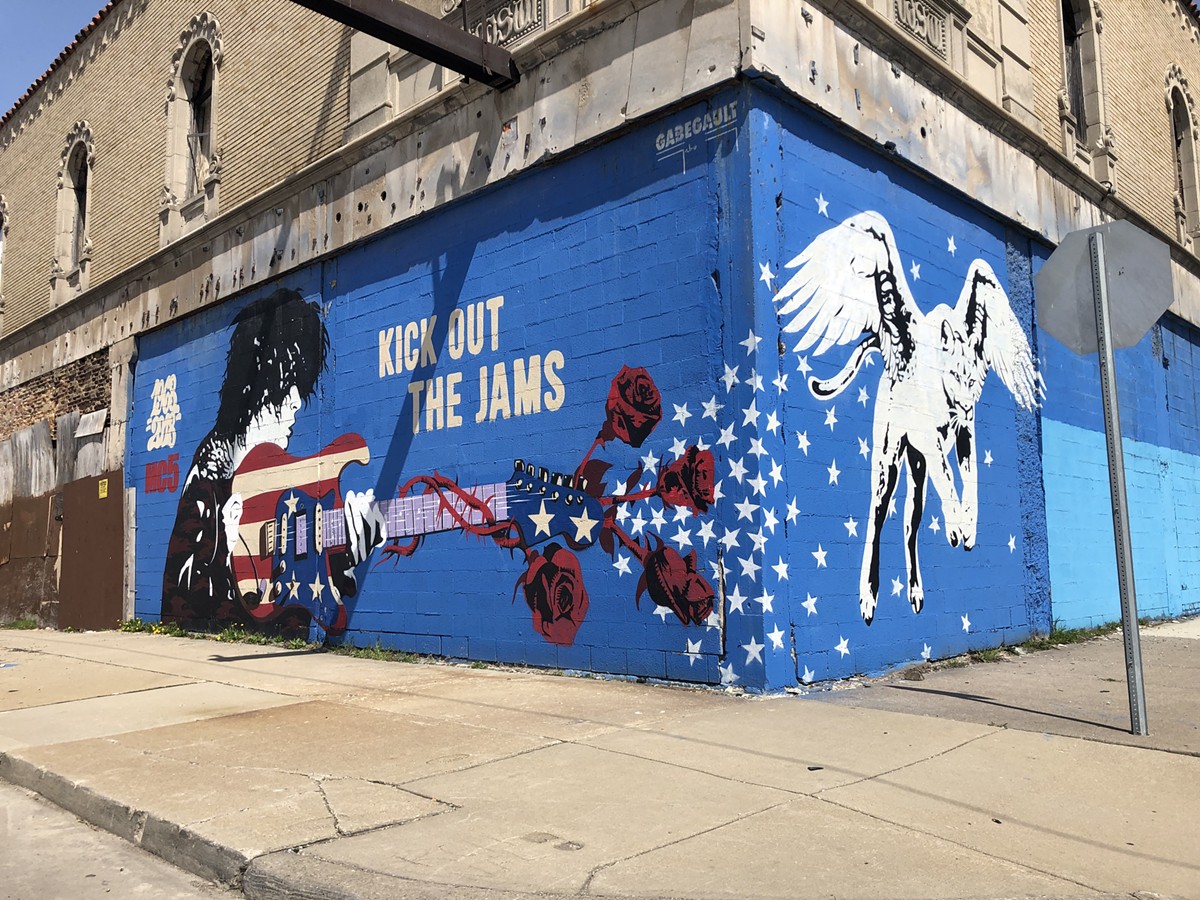

Kramer’s death jolted the popular music world all the way down to those of us who hung around the Grande Ballroom on Grand River Avenue on Detroit’s West Side in the late 1960s and early 1970s, when and where “The Five” were the house band and life was grand.

Personally, I was surprised to discover how many deep feelings were stored behind my memory doors. They were spurred by chats with old friends, by re-reading Kramer’s 2018 book, and by listening again to the band’s defining album (and song) called “Kick Out the Jams” and recorded in late 1968 live at the Grande.

The song touts “the sound that abounds and resounds and rebounds off the ceiling … ‘Cause it gets in your brain, it drives you insane … the wailin’ guitars, girl, the crash of the drums, makes you want to keep a-rockin’ ‘til morning comes …”

Although Kramer and the MC5 are not in the Rock & Roll Hall of Fame, they are curiously mythical icons in the collective consciousness of rock music as an art form. Some rock historians consider them prophets of the punk era, which followed them by a decade, when Kramer was imprisoned.

Even the Clash opened a song called “Jail Guitar Doors” with a reference to Kramer’s conviction for dealing cocaine. So a tribute to Kramer was wisely inserted into last Sunday’s Grammy awards during a segment honoring those who had died in the previous year.

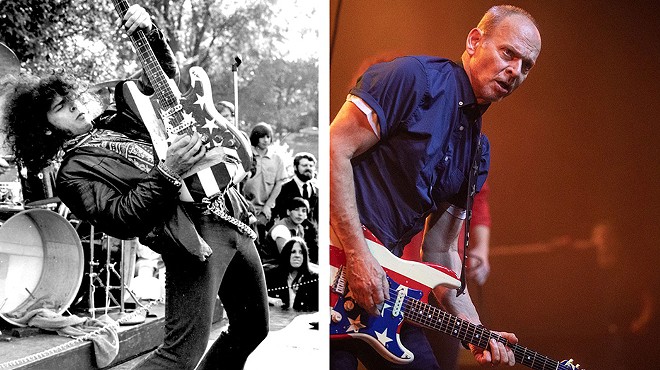

The screen on the national telecast showed a misty photo of young Kramer, performing on stage, with long hair and long sideburns, wearing shades and wielding a guitar painted like the American flag.

“Wayne Kramer,” the words on the screen said. “Co-founder, Guitarist, Activist. MC5.”

I saw the MC5 at least a dozen times, mostly at the Grande, but sometimes at other venues. One of my favorite shows was in 1970 at Tartar Field at Wayne State University, a school I attended at the time to study journalism.

A friend had a Super 8 color movie camera so we bought a few rolls of film and stood close to the stage and got some good action shots of the Five flailing away. Sorry to say, the pictures still exist but the film is — and always was — silent.

To properly capture the essence of an MC5 show you had to both see and hear them. And I don’t think we had money at the time for sound film or a sound camera. No cellphones, then, either. Fortunately, other cameras were there and one of them recorded an excellent version of “Kick Out the Jams.”

The sound video on the internet looks to be a black-and-white recording that has been colorized.

Others interested in a longer crash course about the MC5 should listen to the entire album, which lasts about 40 minutes. Those of a certain age, upon honest reflection, might find the music much more mediocre than it is in our memories.

The best and most melodic cut on K.O.T.J. is “Motor City is Burning,” and that was written and first recorded by John Lee Hooker. At the end of it, Tyner ad-libs, “I may be a white boy, but I can be nasty.” Along with their manager, John Sinclair, the Five helped found the “White Panther Party.”

Kramer sings the lead in “Ramblin’ Rose,” his voice a high tenor, bordering on a cartoonish falsetto. Some lyrics of other songs reflect sexist rock tropes of the time, including “Wham, bam, thank you ma’am, I’m a born ass-pincher and I don’t give a damn.”

As for the psychedelic “Starship,” well, let’s just say you can’t dance to it and that the late 1960s featured the occasional blend of strange musical sounds influenced by controlled substances and space travel fantasies.

But music was just part of the package that came with the MC5. If you were a guy on the cusp of high school and college at the time, the draft and the war in Vietnam were daily worries. So was getting busted by cops for marijuana.

The Five took the left-wing, liberal side in those debates and also opposed police brutality after Detroit’s Riot and Rebellion of 1967. Importantly for the Motor City sensibility, they pushed a blue-collar, chip-on-the-shoulder style and attitude of what are sometimes called factory rats and working class.

They acted more streetwise than the draft-deferred college kids protesting, sometimes violently, on their pretty campuses in the countryside. They even posed bare-chested for photos with rifles and gun belts, a stance steered by the extremist politics of Sinclair, who later became Michigan’s marijuana martyr.

After Sinclair went to Jackson State Prison in 1969, the group began to falter. Despite his general bluntness, Kramer treads delicately over the break with Sinclair and their eventual reconciliation.

“John and I have never discussed what happened between us,” Kramer writes. “We both have our own perspectives. It was extremely painful … I’d always loved John and I was happy to have my old friend back.”

In some ways, the most gripping parts of Kramer’s book describe his life before the MC5’s success — when he was physically abused by his step-father — and his after-life following the demise of the band, when he became a home burglar in Oakland County, a drunk, a junkie, a drug dealer, and a federal prisoner.

He grew up in various places including Harsens Island, Detroit’s West Side, then the Downriver suburbs, sporting what he calls “greaser” style and moving from rental to rental with his mother, who fixed hair and worked in bars and drifted from man to man, one of whom abused both Kramer and his sister.

His real father was a “shell-shocked” World War II veteran who turned to alcohol and drifted away, leaving his son exposed and vulnerable.

“My mother called him a ‘rat’ and a ‘bum,’” Kramer writes of his real dad. ““My grandpa was a mean alcoholic … He was loud and a bully … Herschel abused me … I couldn’t believe this was happening to me. No one ever said anything about it afterward … It was family fun — if you lived in the ninth circle of hell … Fighting was part of boyhood then … There was power in stealing. It became my thing …”

Much of the writing is blunt and confessional, evoking the gritty style of Charles Bukowski, especially when the band breaks up and Kramer’s life turns into a tailspin of addiction and crime. He even mentions Bukowski as one of his heroes.

“Crime had an allure for me,” Kramer writes. “I have identified with and romanticized outsiders … I was desperate. A dope habit requires cash every day … Eventually, I ran out of things to sell …”

He writes of avoiding a possible execution during a shady drug deal in the Pick Fort Shelby hotel in downtown Detroit.

“No witnesses meant Leon and Barker were going to kill everyone in the room — Tim Shafe, the Bug, Tony and me, too,” Kramer writes. “… The Bug left Detroit and was never seen again. He was always a slippery dude …”

Especially when recounting the rock star life, Kramer comes off like a junior varsity Keith Richards, whose autobiography called Life — published in 2010 — also recounts the lifestyle of that era among that fast crowd.

“We were on the cover of Rolling Stone,” Kramer writes.

Importantly for the Motor City sensibility, the MC5 pushed a blue-collar, chip-on-the-shoulder style and attitude of what are sometimes called factory rats and working class.

tweet this

He tells of playing on the same bill with Janis Joplin on the West Coast and turning down her offer to meet up later at the hotel. As for the Velvet Underground: “They avoided us and our people completely. Not that I blame them, considering how deranged and aggressive we must have seemed.”

Some memories are pleasant. He dined in Berlin with Marianne Faithful. Some anecdotes are hilarious. At one show, “my super tight stage trousers ripped open at the crotch” when Kramer wore no underwear. Many other scenes in the book are just as visual and seem like parts of a movie script.

One that was serious came in Lower Manhattan, when a local street gang called “The East Village Motherfuckers” decided the Five were not real revolutionaries but mere sellouts to the exploitative and capitalist record companies.

So they protested an MC5 show at the Fillmore East.

“The Motherfuckers bum-rushed the stage and started trashing our equipment,” Kramer writes. “I watched as knives slashed through the fire curtain, while mayhem exploded out front. Cymbals were crashing, amps were knocked over and there was a lot of yelling and cursing.”

And those were the best of times.

Fast forward a bit, with Kramer out of prison after three years, still struggling, drinking and drugging, doing handyman work, scoring occasional musical gigs and drifting through cities like New York and Nashville, damaging personal relationships all the while.

“Eve had finally decided that being the girlfriend of a touring, drug-addicted, criminal musician wasn’t exactly what she had in mind,” he writes. “A group of small-time crooks and scam artists comprised my social circle. I was on a trajectory straight into the gutter.”

In what amounts to a happy ending, Kramer finishes The Hard Stuff with his account of sobering up, marrying, settling down, adopting a son, helping prisoners reform through music, and enjoying accolades from several generations during his various revival tours up through recent years as a senior citizen.

“The beats of my life break down pretty simply: childhood, the MC5, crime, prison, sobriety, service and family,” Kramer writes. “… I am at peace with my past … I still live in the tension between the angel and the beast … The struggle will continue until the day I depart.”

Subscribe to Metro Times newsletters.

Follow us: Google News | NewsBreak | Reddit | Instagram | Facebook | Twitter