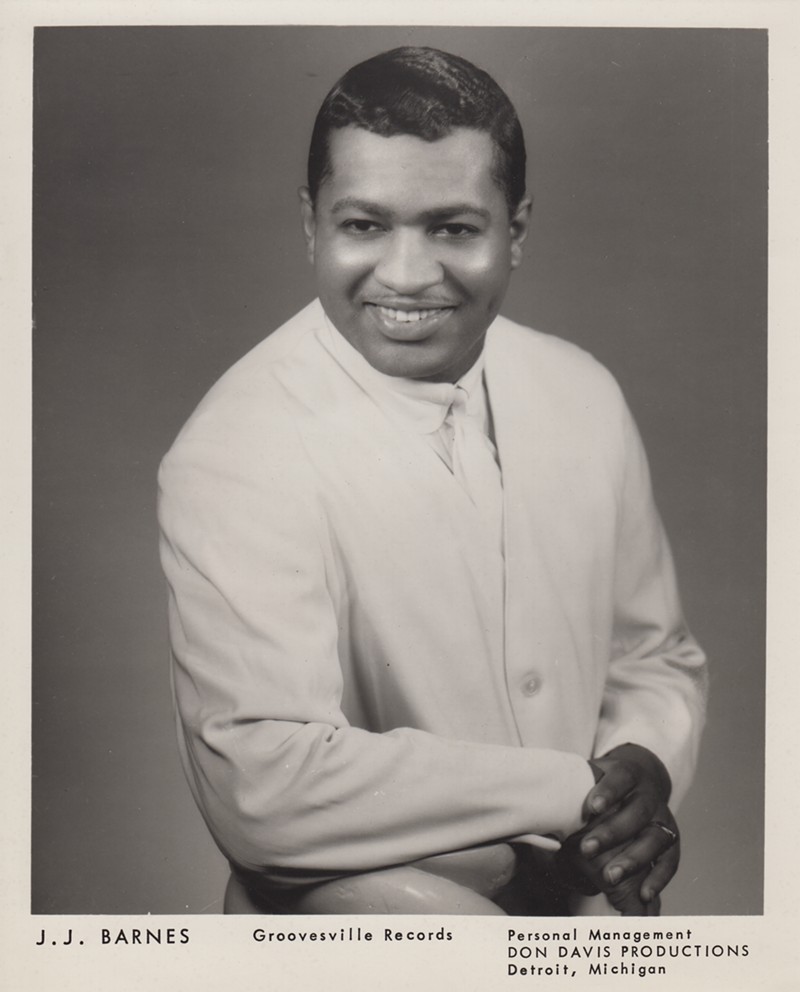

Recorded and released in early 1967, this pleading and plaintive chorus was about a love affair gone wrong, but in the year 2022, it’s more of a love letter to the incredible 60-plus-year singing career of Detroit soul man J.J. Barnes: “Darling your chains of love won’t set me free/ your chains of love won’t let me be.”

Waxed for local indie label Groovesville, “Chains of Love” was the B-side to his break-away Billboard R&B chart single “Baby Please Come Back Home.” Though it wasn’t the side getting airplay in 1967, “Chains of Love” and several of his other singles have endured and experienced rediscovery within subcultures both at home and abroad.

Slim and agile, the silky voiced singer is prepping for a headlining performance on Sunday for the Detroit A-Go-Go festival at the St. Regis Hotel Ballroom. It could also be his last.

“I’ll never fully retire, but this might be the last in-person appearance I’ll ever make,” says the nearly 80-years-old Barnes. “I’m almost blind in one eye, I’ve got high blood pressure, and a bad foot. But I’ve still got my piano at home, and I play and write every day.” Despite managing the typical maladies of a near-octogenarian, Barnes is sharp-witted and super clean in an all-white outfit and matching white Buffs-style sunglasses.

As a member of an incredible generation of Detroiters, Barnes grew up within a fertile music scene that birthed jazz, soul, and rock legends who are now household names the world over. In the 1960s he was signed to both the Stax and Motown record labels, and starting in the 1970s, he enjoyed fame in the U.K., where his records were foundational cornerstones of the country’s northern soul scene. In the early 2000s, Barnes’s music saw another revival via garage rock band the Dirtbombs.

At a sit-down interview conducted days after the federal government announced plans to issue a $105 million dollar grant to Detroit to finance the removal of the sunken I-375 freeway and rebuild part of the city’s former Black Bottom neighborhood, Barnes proudly proclaims, “I was born in Detroit, raised right there in Black Bottom, right off Hastings,” he says, placing a pointed finger upon the table for added emphasis. “I think it’s a great idea to re-raise I-375.”

Jumping back in time to Detroit in the early 1940s, just before that same federal government initiated the Federal-Aid Highway Act that financed the demolition of the African-American neighborhood, it was the best of times and the worst of times. The arsenal of democracy was raging. The Rouge steel plant’s blast furnaces roared night and day, barely keeping pace with wartime manufacturing demands. Detroiter Joe Louis was heavyweight champion of the world, and high-class night clubs like Sunnie Wilson’s Forest Club hosted acts like Charlie Parker, Nat King Cole, and Dizzy Gillespie. The good times called, but existing tensions between white and Black migrants, combined with extremely limited and dangerous housing conditions for African Americans in Black Bottom, boiled over into a devastating riot on June 20, 1943 where, in one weekend, 35 people were killed — 25 of whom were Black.

It was into this both prosperous and volatile world that Jimmy “J.J.” Barnes was born to Leroy and Eddie Mae Barnes, née Yelder, on Nov. 30, 1943. “My parents split up early on, and I really didn’t know my mother for the first part of my life,” Barnes says. “The conditions were rough, and the house on Hastings was always damp. As a child I got pneumonia real bad. My father took me to a woman named Mama Lena who owned a newer home but ran it as a ‘Hoe House’ on the corner of Brush and Forest. He told me later that he took me there expecting me to die, but Mama Lena took me and wrapped me in a blanket and poured oils on me. I started hollering and she said, ‘He’s OK now.’ I got a lot of love from Mama Lena.”

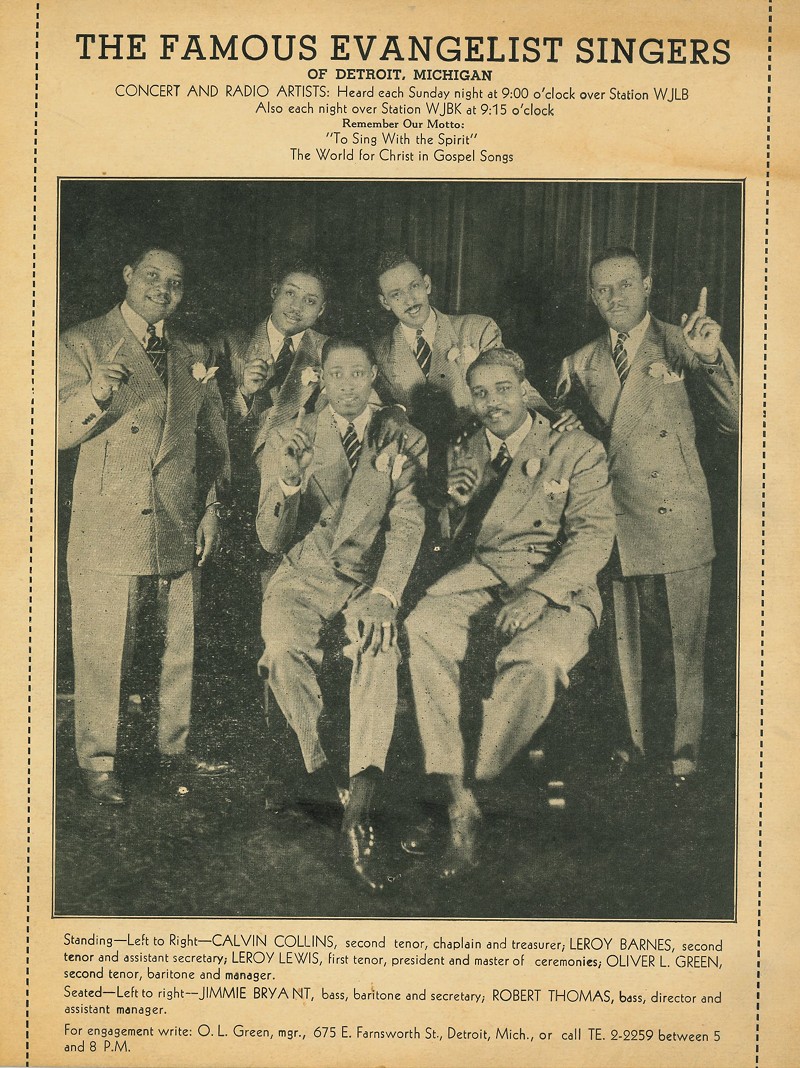

Barnes’s father was a full-time member of the Detroit-founded but nationally renowned gospel group the Evangelist Singers. The group, who would later change their name to the Detroiters, released several powerhouse gospel 78 RPM shouters like “Let Jesus Lead You” on Art Rupe’s Los Angeles-based Specialty Records. The Detroiters crisscrossed the country playing the gospel circuit with guitar slinger Sister Rosetta Tharpe and the Fairfield Four, playing a storming style of hard-shouting, foot-stomping gospel that would influence and inform first-generation rock ’n’ rollers like Little Richard, who released his most famous records on the same Specialty record label. The never-ending touring was great for the group, but, coupled with the poor living conditions at the family home and the deteriorating relationship between his parents, Barnes was left to live with Mama Lena for the first seven years of his life.

“Even though she led that type of life, Mama had me baptized at New Grace Bethel Church on Forest, and she put me in school at Trowbridge Elementary,” Barnes says. Seven years passed before Barnes would be reunited with his biological mother. “My mom remarried a man named Earl Williams, and somehow they came and found me,” he says. “They took me, but I didn’t even really know these people at the time.” Though Barnes was uprooted from a loving environment, he quickly grew attached to his musically inclined family, which now included a sister with a powerful voice, Ortheia Barnes, and a gospel-singing stepfather who was a member of a popular and long-standing quartet the Cumberland River Singers.

With music all around him, singing was now an integral part of Barnes’s life. At the age of 15, a friend named Johnny Starks helped him land his first professional gig in his gospel quartet the Hurricane Travelers. The Hurricanes were local stalwarts, and just prior to Barnes joining, they waxed their debut 78 record for the wonderfully ramshackle mom and pop Detroit label Fortune Records. The debut disk titled “He’s All I Need” sold well enough to kick-start a career for the group that would last well into the 1990s.

“As I turned 16, I started hearing rock ’n’ roll and R&B,” says Barnes. “I heard this new music and wanted to be part of it.”

Amazingly, the mailman who delivered to the Barnes’s home also ran a record label. Mailman Fred Brown had recently initiated his Kable and Mickay’s imprints, and knew a good thing when he heard it. While walking his delivery route, Brown overheard the Barnes family singing and harmonizing together. The mailman promptly signed Barnes, his sister Ortheia, and his stepfather’s group to contracts with his company.

The deal marked the end of Barnes’s tenure with the Hurricane Travelers, but success and exciting industry contacts soon followed for the teenage singer. Released in early 1960, Barnes’s first record “Won’t You Let Me Know” included a who’s who of young studio musicians. The group — consisting of Benny Benjamin on drums, Joe Hunter on piano, Don Davis on a gnarly lead guitar, and bassist James Jamerson on stand-up acoustic bass — would go on to form the core of the Motown studio band the Funk Brothers.

The disc premiered on Nashville’s seminal radio station WLAC. With its unregulated bazillion-watt radio signal, WLAC’s broadcast reached from Jamaica to California to Michigan, so Barnes was nationwide right out of the gate. The crafty Brown had another promotional trick up his sleeve that also kick-started the career of the then-mostly unknown Martha Reeves. Reeves’s vocal group, who were still calling themselves the Del-Phis, sang backup on Barnes’s disc, and then promptly recorded an answer song, called “I’ll Let You Know.” In her autobiography Dancing in The Streets, Martha Reeves called it “a fleeting moment of glory … now we knew what it felt like to hear ourselves on the radio.”

“The first show I ever did was at the Graystone Ballroom in Detroit at a Frantic Ernie Durham record hop,” says Barnes. “I was there to promote ‘Won’t You Let Me Know.’” The pioneering radio DJ loved the record and put it into rotation on WJLB. Moreover, he gave the young singer advice about show business.

“That night at the Graystone, I was just so excited,” Barnes says. “I was out in the crowd going crazy, dancing with all the girls I could. Ernie grabbed me and said, ‘If you are gonna be a star, act like a star!’ He sent me back-stage to get ready and focus on the show.”

Barnes stayed with label owner Brown through 1965. Together they released several more good records, but as gritty R&B transitioned into the danceable, polished, four-on-the-floor sound recognized as Detroit soul, Barnes moved to a fresh, new label.

Ed Wingate was a large man. Standing over six feet tall and weighing in around 300 pounds, Wingate had the money and the muscle to make noise in Detroit’s soul music industry. Starting in the mid-1940s, the streetwise Wingate had hustled his way up to the top. In 20 years’ time, Wingate’s diverse business holdings grew to include the prestigious 20 Grand club, a chain of hotels including the infamous Algiers Motel, the still-extant City Cab Company, and, importantly for this story, a series of record labels, including Golden World and Ric-Tic.

More than any of those streams of income though, Wingate’s fortune was built upon the street gambling operation known as “The Numbers,” an ubiquitous street lottery that, though illegal, was tremendously popular in mid-century America. In his book Custodians of The Hummingbird, Detroit soul man Al Kent estimates Wingate took in more than $50,000 dollars a day from the Numbers. The speculation is furthered in Bridgett M. Davis’ brilliant book The World According to Fannie Davis: My Mother’s Life in The Detroit Numbers, where she repeats assertions of Wingate’s supremacy in the Numbers racket by saying, “My momma eventually had several books, up to ten at her height. This was small compared to a major numbers man like Wingate who reportedly made millions a year in his heyday.” Wingate would keep the sorted stacks of money separated into $20,000 bundles, perhaps a nod to, or impetus for, his famous nightclub’s name, stacked to the ceiling in the closets of his Boston-Edison estate. Moreover, his Golden World musical enterprises were successful and second only to Motown in terms of output, Billboard chart success, and monetary gains.

Wingate used a few of those bundles to purchase a building and finance the construction of a custom-built, state-of-the-art studio at 3246 W. Davison St. in Detroit. Ric-Tic was one of the labels that used the studio, and it’s there that Barnes matured as an artist and began to make musical magic, releasing four 45s. While each is a gem, the third disc, “Real Humdinger,” has, to quote its lyrics, “soul worth its weight in gold.” The classy, pop-inflicted mid-tempo burner is a cornerstone of the singer’s recorded legacy.

Songwriter Al Kent recalls an inspired session at the Golden World studio. “The spring sun slanted into the hallway,” he says. “The song just seemed to stand on its own two legs and walked off.” When it came time to record the musical backing, the team hired the best in town, but bassist James Jamerson walked in 20 minutes late. When Kent said, “You’re late James!”, Jamerson replied with a wry, “And I’m drunk, too!’” Despite the soused bass man, the rhythm section is locked-in and on fire, and the track is an underground Detroit soul classic that still fills dance floors. The record was a big local hit, but the label itself soon became a victim of its own success.

“We didn’t want Wingate to sell out to Berry,” remembers Barnes. Ever the hustler, Wingate had done the unthinkable. By signing talented artists like Edwin Starr, George Clinton’s the Parliaments, the Reflections, and Barnes, and by building a world-class studio, the little-label-that-could on West Davison had succeeded in making the big boys on West Grand more than a little uncomfortable. But more than just recognizing and neutralizing a local artistic threat, Berry Gordy and his Motown empire were also in need of an additional recording studio to accommodate the onslaught of recording dates they had on the books. Just 18 months after opening for business, Wingate accepted an offer somewhere around the $1 million dollar mark for his Golden World enterprises. The deal included all the label’s recordings, the studio, and the recording contracts of Starr and Barnes.

“Ed called me into his office, and said, ‘I made a deal with Motown. You’ll have to deal with them from now on,’” Barnes recalls. “And that was it. I went over there and talked to [Motown exec] Ralph Seltzer. We made a deal, and right away I started recording for them.” At the height of his artistic abilities, Barnes was finally and officially in the major leagues.

Recording dates quickly ensued, resulting in storming soul stomps of the highest order. But much to Barnes’s dismay, stellar sides like “Show Me the Way” and “Every Time I See You, I Go Wild” languished on the shelf. The problem was soon made clear to Barnes.

“Eddie Holland came to me and said, ‘I just left a meeting with Berry (Gordy), (Harvey) Fuqua, and Marvin (Gaye),” Barnes recalls. “Marvin is bitching and bitching and just going crazy up there, man.’” Apparently, Gaye felt that Barnes sounded just a little too much like him. “Eddie asked if I could change my style,” he says. “I said, ‘change my style?’ I’ve been singing like this all my life!’”

The fact was, neither Barnes nor Motown were ever entirely comfortable with each other. “Not long after that, I was standing by myself on the front porch of Motown and Marvin came up behind me and whispered in my ear, ‘You a bad mother fucker’ and then just walked off,” he says. “I didn’t really know how to take that.” Frustrated and uneasy with his surroundings, the singer made his mind up to leave Motown.

“I got a release from Motown, but they got the rights to the things I had recorded for them,” he says. Fortuitously however, just before he left the company, the Motown family provided one parting gift in the form of an assist from Stevie Wonder. “I was in the studio working on my song ‘Baby Please Come Back Home,’” he says. “Stevie Wonder walked in and said, ‘I like that, can I try it?’ I thought ‘Hey, you’re Stevie Wonder. Go ahead!’ He helped me with the changes, and I offered him a writer’s credit, but he said he didn’t really deserve it and told me to keep it. Stevie said, ‘This is going to be a big hit for you.’ It was like he prophesized it. It turned out to be the biggest hit of my career.”

Barnes walked out of Motown, but some of the best days of his career were ahead. Re-partnering with his old pal Don Davis who now had the Groovesville record label, the two were quick to record and release the Wonder collaboration, which was backed with the Melvin Davis-penned “Chains of Love.” The record hit the streets in early 1967, and it raced up local and Billboard charts. Landing in heavy rotation on the influential and powerful CKLW and WKNR radio stations, the exposure landed Barnes on shows with big names like Otis Redding, James Brown, Deon Jackson, and old pal Martha Reeves.

Pulling double occupational duty as a radio DJ and a television host, Rockin’ Robin Seymour had been an on-air personality since the 1940s. By the mid-1960s, Seymour’s raucous and wildly popular daily television dance show “Swingin’ Time” was an institution with local teenagers. Seymour loved “Baby Please Come Back Home,” and he put the song in heavy rotation on his broadcasts. In the summer of 1967, Seymour scheduled a live concert celebration of his show. Assembling an all-star review of Detroit’s top soul acts, he booked the beautiful Fox Theatre for a ten-day engagement. As an indicator of his popularity, Seymour put Barnes’s name just underneath headliners Martha Reeves and the Vandellas on the Fox marquee.

July 23, 1967 is an unmistakable date in the history of Detroit. As the early hours of a Saturday night spilled over into a Sunday morning, a group of Vietnam veterans and their friends were celebrating their safe return from overseas combat at an illegal after-hours soul club located above the Economy Printing Company on Twelfth Street. Detroit Police had staked out the party and made their move to clear the club. As they marched people down the stairs and into the street, large crowds gathered around them to protest the arrests. Violence and unrest erupted, and Detroit’s rebellion began.

That Sunday also marked the last day of Seymour’s Swingin’ Time Revue at the Fox. It was a matinee performance, and, without an understanding of exactly what had happened on Twelfth Street and how it would escalate, the show was well underway before the seriousness of the situation was known to Seymour or the performers. “I had just done my show and had come off stage.” Barnes remembers. “Somebody ran into the Fox and was shouting, ‘It’s a riot!, it’s a riot!’”

In her autobiography, Reeves relates the irony of singing “Dancing in The Streets” just before event staff waved her off stage and informed her of what was happening. The gig was over. She was then assigned the unenviable task of informing the audience of the situation and asking them to leave in an orderly fashion.

“After the guy ran into the Fox and yelled at everyone, I went out the side-stage door to see for myself,” Barnes recalls. “People were running wild, breaking windows and grabbing stuff. I went back in, and then I started yelling, ‘It IS a riot!’”

Barnes grabbed his stuff and ran to his car. He considered heading to the Algiers Motel. “It seemed like a quick way to get off the streets,” he says. “Wingate owned it, and we would stay there. When I got there, something told me to just go home. I’m so glad I didn’t stop.”

It was a fortuitous split-second decision. Also on the Swingin’ Time Revue show were fellow Golden World alums the Dramatics. The 2017 Kathryn Bigelow film Detroit depicts the horrific torture members of the group would endure as part of the Algiers motel incident, where three civilians were killed by a riot task force.

“The riot kind of killed the music, or at least it changed it,” Barnes says. “It was a different mood. I had a booking scheduled at the Apollo right after the Fox, but that got canceled.”

Barnes had really excelled in the upbeat, major-key dance-crazed world of mid-’60s soul, but in the book Detroit 67: The Year That Changed Soul, Scottish author Stuart Cosgrove details how political movements, LSD, and heavy, psychedelic-soul music moved in and changed popular music culture. Despite a brief tenure with Stax records in Memphis, the late ’60s and early ’70s were a little slow for Barnes.

But over in the U.K., a new dance craze was happening. In the bestselling music book Last Night A DJ Saved My Life, authors Bill Brewster and Frank Broughton describe the U.K.’s northern soul scene as “the first rave culture.” The scene started in the early 1970s with a series of clubs and obsessive DJs in the north of England. Though the energetic music they loved was already a few years old when they began to rediscover and reintroduce it to a new audience, the propulsive rhythms and positive message of the American music garnered a rabid cult following. They threw wild all-night parties in places like the Wigan Casino, which was similar in construction to Detroit’s Grande Ballroom. Young Brits, turned on by the danceable sound of mid-’60s Detroit and a huge supply of amphetamines, crowded into clubs to dance to soul 45s until daylight.

“Edwin Starr first told me about northern soul,” Barnes says. Starr told him “Humdinger” was so hot over there, that “they make me sing it,” Barnes recalls.

“I got my first passport in 1973 and flew right over to a sold-out show at the 100 Club in London,” Barnes says. “I wore out three passports going over to the U.K.”

In the U.K., Starr was living large in a castle. “I mean a real deal castle!” Barnes recalls. “He had a four-car garage that was always full. He used to store a car for Junior Walker. I loved staying there when I went over, it was unreal.”

Always on the hunt for new-to-them sounds, the northern soul DJs mined the depths of Detroit’s indie-underground labels like Ric-Tic, and “Real Humdinger” was on the top of their playlists. The song enjoyed such a resurgence in popularity that Gordy and Tamla-Motown, who still owned the Ric-Tic masters from the Wingate deal, reissued the song to meet demand for the disc. Barnes finally had a record on Motown, regardless of how Marvin Gaye felt about it.

The obsessive partiers in the north of England kept Barnes flying back and forth overseas through the ’70s and ’80s, but he wasn’t done at home. Released in 1977, the record “The Erroll Flynn” was a nod to Detroit street gang the Erroll Flynns. The gang was a notorious but fashionable and party-centric group whose most infamous exploit involved sticking-up the entire audience of a Kool and the Gang concert at Detroit’s Cobo Hall on Aug. 15, 1976.

“I saw this gang runnin’ around the hood,” Barnes says, laughing. “I wasn’t in the gang, but they did this dance with their hands in the air, and it looked great.” The dance was, in fact, an intentional means of self-identification for the gang. A trained eye could identify the various sects by the varied dance moves. Eventually the dance would morph into and influence the now celebrated regional dance culture known as “jit.”

Barnes’s song was a little watered-down disco, but the street origins of the lyrics, “you know this dance came from Detroit,” are a lot of fun many years later. “I took the song to Nat Morris on the television show The Scene, and he said, ‘It’s gonna cause a controversy,’ but we put the record out and it did OK,” he says.

Fast-forward to the early aughts, and Detroit’s Cass Corridor is alive with cheap Pabst, expensive Diesel jeans, and vintage fuzz pedals. An ex-drag show bar-turned-alternative music and performing arts space called the Gold Dollar helped to launch a revitalized sound in rock music. The so-called “garage rock” movement and its emphasis on energy and the youthful idealism of danceable, pre-Cream rock ’n’ roll had many area bands back to kicking out the party jams. Many bands were formed, some signed deals, and at least one went on to win multiple Grammy awards.

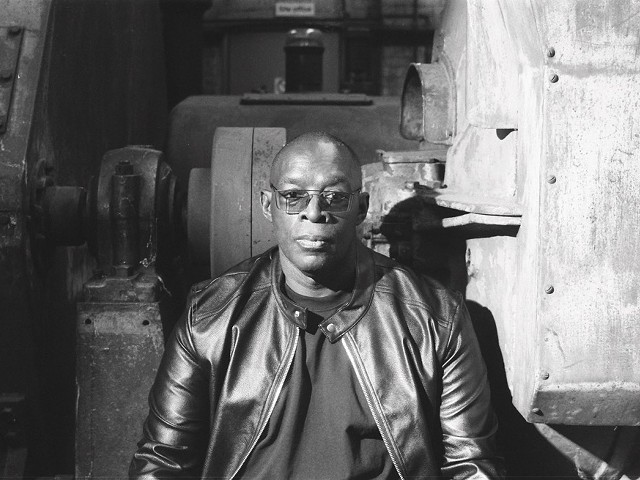

At the top of the heap of notable bands was a supergroup called the Dirtbombs, whose super cool, sunglass-wearing, guitar-playing frontman Mick Collins had always been obsessed with music, growing up in a household with a large record collection. Stuffed into one of the boxes in the basement was a copy of Barnes’s “Baby Please Come Back Home,” with the B-side “Chains of Love,” and its rock-ready riff.

“I’ve had that 45 my whole life,” Collins tells Metro Times. “One of my sisters probably bought it, right when it came out, and over time, it made its way into the basement with the rest of the records no one wanted anymore, until I came along.”

Collins says he forgot all about the single until his friend and Gories bandmate Danny Kroha bought it at a record fair, inspiring him to go home and reappraise it.

“I can’t remember when I made the decision to record it,” Collins says. “I probably thought about covering the A-side, then flipped it just ’cause I hadn’t heard it in a while. No idea. But the next thing I remember is laying the guitar part.”

He adds, “We knew we had a winner.”

Released in 2001, the Dirtbombs’ Ultraglide in Black was the band’s magnum opus, a collection of largely covers reworked as rock songs. It reached large international audiences and sent the band jet-setting to and from Europe and beyond. Its opening track chimed a familiar flattened third. In the hands of Collins, his guitar, and a cranked-up fuzz pedal, Melvin Davis’s old intro piano riff to “Chains of Love” sounded the clarion call to rockers world-wide who were seeking more soul and honest-to-goodness fun than what bands like Limp Bizkit and the Woodstock ’99 era of toxic rock had been offering.

The song became a fixture in the Dirtbombs’ raucous live sets. “I frequently think about retiring it, but in reality I know better: it’s one of our trademark songs and it isn’t going anywhere,” Collins says. “As long as people want to hear the Dirtbombs, they’re gonna hear ‘Chains Of Love.’”

“‘Chains of Love’ is probably the song I’ve played live most often in my life,” Dirtbombs drummer and Third Man Records co-founder Ben Blackwell says. “I’m just forever grateful to have played a small part in continuing the Detroit legend for future generations to explore.”

A few years after its release, the Dirtbombs’ rollicking rendition of “Chains” caught the attention of renowned painter and art-house film maker Julian Schnabel, who featured the song prominently in his 2007 film The Diving Bell and the Butterfly. The film, which received four Oscar nominations and a Cannes Festival Best Director award, is an adaption of a novel written by a Jean-Dominique Bauby, a French editor of Elle magazine who had suffered a massive stroke and had become almost completely paralyzed, and dictated the sometimes-whimsical book to a ghostwriter using a series of eye-blinks. Incredibly, Bauby died two days after the novel’s publication.

The lively and relentless energy of the Dirtbombs arrangement of “Chains of Love” was a perfect fit for the film, which celebrated life down to its smallest sensations. “I kind of wish they had used my version,” laughs Barnes. “But I talked to the band on the phone just before they went overseas with it, they were cool, and their take is great. I still get paid a little from it.”

According to Barnes, “My biggest fans are in Europe.”

Enter one energetic Englishman named Phil Dick. In an interview conducted via email, the Leeds, England, native exudes praise. “J.J. Barnes is one of the most beloved artists on the U.K. northern soul scene,” Dick says. “His performance at the Ric-Tic Revue in Hinckley, Leicestershire, is still spoken in reverential terms some 40 years after it happened. His vocal delivery just struck a chord with us kids up north.”

Dick is the organizer of an incredible local-but-not-local music festival called Detroit-A-Go-Go. Though staged locally, it is organized and attended almost entirely by people from the United Kingdom. From overseas, Dick and his team book a week’s worth of musical events in Detroit. Then, in an incredible show of fandom, planeloads of his U.K. “Soulie” friends fly into Detroit, rent out a large portion of the St. Regis Hotel, and throw one hell of a soulful party.

The event brings English northern soul fans to their mecca, showcasing DJs playing coveted Detroit 45s to a busy dancefloor, a big list of revered singers, a full backing band, and a gala ball at Gordy’s former manse in Boston-Edison.

It could also be the end of an era.

“As of now, this is going to be the last Detroit-A-Go-Go,” says Dick. Given the difficulty and expense of organizing the event from Leeds, the finality of this year’s festival is reasonable enough; still, the conclusion of the concert will be a loss locally as it has offered performers a chance to reach a core part of their U.K. audience without leaving their hometown.

“Phil brings his own crowd with him; he doesn’t really need to rely on Detroit crowds,” says Barnes. As he is nearing 80 and local gigs don’t come knocking very often, the veteran performer has decided that this final A-Go-Go will be his last live performance too. His previous performances have been electrifying. His voice is still strong, like silk dragged across just enough gravel. His version of the underground soul classic “Our Love Is in The Pocket” will be on the set list, and it’s a showstopper.

Also on the show are Motown alums Kim Weston, Carolyn Crawford, and the Contours. But the Brits reserved that headlining slot on Sunday, the last night of the last A-Go-Go, for J.J. Barnes.

It will be a special performance celebrating a long career. From Black Bottom storefront churches with the Hurricane Travelers to the Cannes Film Festival in France with the Dirtbombs, the chains that bind the man to his music have created a worthy body of work and a deeply Detroit musical story.

J.J. Barnes will perform as part of Detroit-A-Go-Go on Sunday, Oct. 30 at the Hotel St. Regis Ballroom; 3071 West Grand Blvd., Detroit; 313-873-3000; hotelstregisdetroit.com. Music starts at 8:30 p.m. Tickets are $35 on Sunday. The Detroit A-Go-Go festival starts Wednesday, Oct. 26; see detroitagogo.com for more information, including hotel packages.

Special thanks to Michael Hurtt and Mike Dutkewych for their assistance with this article.

Stay connected with Detroit Metro Times. Subscribe to our newsletters, and follow us on Google News, Apple News, Twitter, Facebook, Instagram, Reddit, or TikTok.