With a group photo shoot planned for Sunday’s Saint Patrick’s Day Parade in Corktown, Sidestreet Diner co-owner Meghan Josefosky shoots those plans to hell around 7 a.m. that morning.

“Unfortunately, I won’t be able to attend the parade today,” her text to me reads. “One of my cooks called in sick so I will be cooking on the line today… But Sheila will be there.”

Such is life for mom-and-pop restaurateurs. It’s always something. And cross-town in Sheila Taylor’s world (Josefosky’s cousin and business partner), it’s something else.

Arriving at Taylor’s restored 1916 Victorian home in Corktown at 11:15 a.m., granted, I’m 15 minutes early. Still, she’s nowhere near ready, coming to the door in little more than a loose robe. Apparently, the previous night’s party I’d been invited to but couldn’t make was a late one.

“So, you’ve got a disco ball on your ceiling,” I can’t help but notice, sitting down to twin sister Siobhan’s offer of Irish Coffee and some stellar corned beef hash that three ravenous Chihuahuas compel me to share.

“Yeah, I’d show you, but we burned out the batteries last night,” Taylor sounds more proud than apologetic.

“We have company?” a disheveled blonde shuffling through the scene shoots me some glassy side eye. “He’s the reporter?” I hear family friend Renay gasp after someone whispers her that info. “Oh, fuck!”

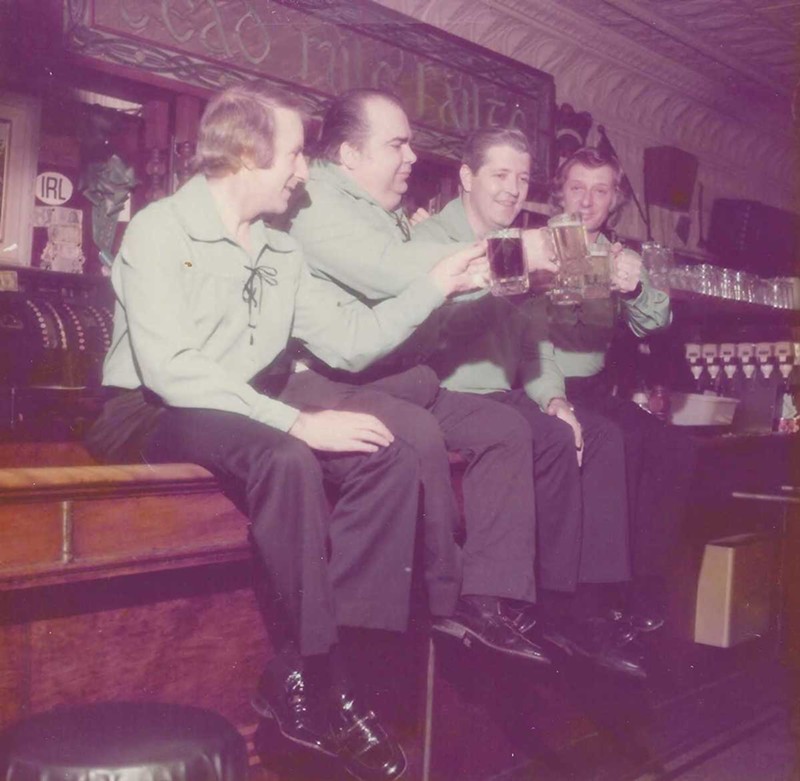

“Too many picklebacks” — Jameson shots with pickle juice chasers — “for that one last night,” Taylor brother Garrett opines before treating me to a few lines and guitar strains of “Momma Don’t Allow,” a favorite family song about the faux Irish folks one encounters drinking green beer and no-no Bushmills on St. Paddy’s — not “Patty’s” — Day, and talking in bad Irish Brogue, which was exactly what I did by saying “top ‘o the mornin’” to Taylor as she let me in. Lesson learned. After a few more tutorials on proper Irish everything, the Taylor Clan walks our talk down Trumbull to the Michigan Avenue parade route, going over more of the family’s proud hospitality history. Stopping atop a pedestrian overpass on the way over to our Gaelic League rendezvous with the photographer, Taylor points out the site of the former Billy Walsh’s Public House, a now-cleared corner of Henry at Harrison, where her classically trained tenor father, Charlie Taylor, left crowds literally crying for more of his Irish balladeering way back when.

First meeting at Sidestreet

Five minutes into my visit to the cousins’ busy Grosse Pointe diner, I hear something that screams cut-above customer service.

“Hey everyone,” server Stacey announces loud and clear enough for every customer in the place to hear, “I see the meter maid out there in the lot looking to write parking tickets. Everybody good?” Hear, hear. Now there’s hospitality. As two customers hop up from their seats and out to their cars, I slide out of my booth for more of a look around. Up at the bakery counter by the register, manager Marjorie confirms my suspicion that some puck-like mini cakes wrapped in foil might be de facto homemade Ding Dongs.

“But we call ‘em Dingalings, so Hostess doesn’t get mad at us,” she winks. Then server Kira calls correct for a Smithwick’s, a red Irish Ale, pronounced “Smiddicks” in proper pub parlance. Everything I hear sounds good so far, and most everything I see appears Gaelic legit. There’s the St. Paddy’s Day countdown calendar up front. Standard. Just like the cead mile failte signage (“100,000 welcomes”) above the front door. And when Josefosky and Taylor sit down to talk, both are frocked in shamrocks and all manner of glittery green finery. Just one recurring décor theme struck me as a bit incongruous, so I inquire.

“Who’s the Elvis fan?” I ask.

“I am not a lunatic fan,” Josefosky says. “Well, maybe not. But the day Elvis died, I got in my brand-new Camaro with a friend and drove down to Memphis. We couldn’t get near Graceland, so we turned around and came back. It was bizarre. And that velvet Elvis, that was given to me 20 years ago by an employee who made his bus driver stop so he could pick it off a pile of garbage on the street. I kept it. And the ceramic bust over there is a similar story. A customer brought it in, just like most of the stuff hanging on ‘Elvis Avenue,’” the nickname for Sidestreet’s restroom hallway. Appropriate, I suppose, since it’s purported the King died sitting atop his own bathroom throne.

Getting down to discussing these cousins’ shared family business history, there’s more music to it.

“My dad was a classically trained tenor,” Taylor says, pride as evident in her voice as its quivering emotion over remembrances of him. “He sang in a Scandinavian opera company, moved us to Milan pursuing his career, then moved us back thinking that wasn’t the right life for a family man with children.”

“And I got my first $5 tip as a five-year-old step dancer at Billy Walsh’s,” Josefosky jumps in, giddy over the recollection. “My wedding reception in 1980 was at her dad’s other place, the Emerald Isle,” then on Outer Drive and Chalmers. When I ask Josefosky about what Irish particulars went into a good wedding shindig, she shoots right back, “Well, a fight’s a must.”

Listening to the ladies, they remind me of how easy good table talk goes down, turning strangers into fast friends. Taylor picks up on the fun I have taking it all in.

“We all got the gift of gab,” she twinkles across the table. “And, yes, we’ve all kissed the Blarney Stone,” which, legend has it, has the power to bestow that gift in exchange for any pucker applied to it. Both Taylor and Josefosky’s fathers put their charmed lips to good use singing for their suppers and spinning yarn at Billy Walsh’s, in operation from the early 1900s into the ’70s, before taking their proprietary plunges. Josefosky’s father Jim Allen went on to own his eponymously named “Backroom” pub on Plum Street, Detroit’s ’60s counterculture answer to Haight-Ashbury. Taylor opened Monroe Street’s Old Shillelagh with partner John Brady back in the mid-’70s, on his hunch that an Irish pub was just what was needed in the middle of Greektown. Some 50 years later, that notion has yet to be proven wrong. Both men — born, raised, and married in Corktown — have quite a legacy living on through their daughters.

“My dad sang and told stories like nobody else’s business,” Taylor says. “Once when we were in Ireland, after being ushered out of a pub at closing time, my dad held court outside with us marveling over the crowd he attracted. When he was done, one woman said, ‘Sir, some kiss the Blarney Stone, but I’m fairly sure you’ve swallowed it.’ That was my dad. The stories were endless. And at the end of every one, you were just glad you were there to listen.”

Proprietary pearls of wisdom

Following up our meeting with one-on-one phone conversations, the ladies and I get down to talking about their time as restaurateurs. Asking them each some of the same questions and a few specific to what they’ve learned individually, both Taylor and Josefosky shed some timely light, along with a few illuminating points offered by a loyal crew who’ve stayed committed to Sidestreet Diner since its 2010 opening. The first thing I ask the partners is about each other.

“There’s yin-yang,” Josefosky says of Taylor. “What she can do, I can’t. What I can, she’s not interested in. She’s straight talk when it’s needed and social media, and I’m more head-down operational, food ordering and kitchen equipment.”

While seconding thoughts on the contrasting-complementing thing, Taylor sees some cousins dynamics at work in the duo.

“I’m more front-of-house. She’s more back,” Taylor says. “We’re agreeable, but she’s still my older cousin, the one who’d scream ‘stay out of my room!’ after catching us licking the sugar cake roses she liked to save there in a box.”

As conversations continue, some of older Josefosky’s wisdoms on proprietary life proved noteworthy.

“I know who I am,” she says of what sustains an entrepreneurial spirit. “And I know exactly what needs to be done once I walk through those doors, whether that’s bussing tables, working the register, or continuing to develop the menu. I’m the diner lady, working on a third generation of customers.” When I share a story of a crusty old restaurant tycoon I knew in Phoenix who professed that making money was the only reason for doing anything in his world, Josefosky bristles. “I’d disagree with that man, respectfully,” she says. “Yes, I said I’d never do this. After watching how hard our parents worked, I told myself I’d never live that life. But then I left a career as a corporate banker, and actually found my true self in this business.”

On the present state of the restaurant industry, “Our competition is stiff,” she says. “Still, we help support a community. We [mom-and-pops] don’t have the purchasing power of our big-box competitors, so our sustainability may rise or fall on how we compete in that arena. Unless mom-and-pops are supported within their communities, the future appears difficult. Eating at a restaurant requires entertaining, so we have to always entertain somehow as well. Someone with $50 to spend at a restaurant has a choice to make: mom-and-pop or chain. Sheila and I and our team have to give that person reasons to choose us.”

“Yes, I said I’d never do this. After watching how hard our parents worked, I told myself I’d never live that life. But then I left a career as a corporate banker, and actually found my true self in this business.”

tweet this

And on getting over the hard times humps, “With my first restaurant [Mack Avenue Diner, ’92-’97], I calculated what I needed to earn daily to break even, while living in my parents’ basement with a newborn and toddler. That was my initial goal. Six months later, I was able to buy a home. Those days were when it occurred to me that I could do this.”

Taylor’s hardships were every bit as considerable once the cousins teamed-up to open Sidestreet in December of 2010.

“As things turned out, I had to have brain surgery eight weeks before we opened,” she says. “I’d started falling down [at another restaurant where she’d worked many years] and lost my job, after which I said, ‘Hey, cousin, let’s open a place together.’ Meghan had to hold down the fort till I got back feeling way better about everything but my new haircut. Then, in 2015, I was diagnosed with breast cancer. Had 16 rounds of chemo and 26 rounds of radiation. I survived. We survived. So did the restaurant. Through all of it. My dad would be very proud of our performance. He didn’t think we’d make it when he first saw the place. He said it looked ‘like a girl who stayed at the party too long.’”

Hard work and humor: recurring themes in conversations I’ve had with all kinds of bar and restaurant owners, past and present. Typically, you either laugh or cry on a daily basis, and usually, a bit of both. Josefosky says the biggest speed bumps on her road to career contentment are constant equipment breakdowns and potentially catastrophic electrical outages.

“When the power went out last year, I literally lived in the restaurant for three-and-a-half days,” she says, “keeping all our refrigeration equipment on life-support with a generator I couldn’t leave, connecting and disconnecting fridges and freezers that had to stay running at regular intervals to keep thousands of dollars of food product safe.”

And there’s troop morale that needs to be maintained as well; tempers that get justifiably triggered which also need to be kept chill.

“With DoorDash and the other delivery services, all the tips go to those drivers, not my people who are actually preparing and packaging those orders,” she says. “No wonder so many former back-of-the-house restaurant workers left the industry to take those delivery jobs. Now, that’s another dance we have to do for revenue. The delivery services make money. Their drivers and we [owners] do too. But servers and kitchen crew doing a lot of the work? No, and it doesn’t make them happy.” (Agreed. Something’s got to give there. Much already has, most likely.)

Even so, Josefosky and Taylor’s servers aren’t complaining. Meter maid nemesis Stacey has been with Sidestreet from the start. So has Kira, who answers a question I’d been wanting to ask a savvy food server of late: How would your income be affected if the state of Michigan instituted a living wage mandate of $20 per hour (in lieu of tips), as is about to become law in California come April and potentially soon across New York City’s food service economy as well?

“I’d be taking about a third cut in pay,” Kira answers candidly.

I rest my case. Generally proposed living wage rates don’t work for a large faction of tipped employees across the restaurant industry. Though a boon to a fast-food workforce (which would come at considerable, added expense to consumers), it would amount to more of a catastrophe than a cure for anything that’s already plaguing the full-service sector. Believe that.

Whatever the future holds for a food industry left reeling from a COVID-19 horror story whose ultimate ending has yet to be penned for posterity, I like the chances for continued success of two hard-working Irishwomen who’ve again sold me on the blood, sweat, and tears theory of all it takes to make a restaurant really work.

“You have to be a warrior,” Josefosky sums it up through her view through the kitchen window. “It’s hot, everyone’s at close-quarters, and every product we put out is being judged dish by dish. You can’t let your ego shatter with every poorly-received plate. I tell our crew that it’s OK to hate each other for three hours at a stretch [during rushes]. Afterwards, we can forgive and forget about it.”

Taylor’s perspective reflects that breezier, front-of-house perspective, which one or two picklebacks, here and there, might help bolster after long, hard days working the dining room.

“People like to have an experience, be part of the scene. Corktown’s exploding,” she says of Detroit’s oldest neighborhood, which has transformed with new bars and restaurants in recent years. “I just think new places really need to figure out what people want. Maybe there’s a little too much style over substance out there at the moment. It’s all over the map. Figure out where you’re at and who you are, then show people a good time.”

All that said, we finish with a limerick composed to appropriately close this tale:

Here’s to those outside poo-pooers,

Who think restaurateurs aren’t doers,

The life they know’s hard,

And so says this bard,

Few are rich entrepreneurs.