In the late autumn of 2016, a large and mysterious body of water appeared inside the bright, expansive Susanne Hilberry Gallery in Ferndale. Artist Ivin Ballen's "Reflecting Pool," a 32-by-20-foot black tarp filled only about ankle-high with water, presented itself as the largest painting the gallery had ever installed.

It was a portrait of the room. When you looked down inside it, you saw the ceiling with its Midwestern flat roof design and the lovely architectural detail of lighting scaffold. During the day, from the vantage point of the back of the gallery, facing the windows at front, the floor painting invited the outside indoors. Leaves that fell in the wind danced on its mirrored surface. The painting seeped into the atmosphere. It hung in the room at 80-percent humidity. Ballen's artwork became one with the space.

His solo exhibition also featured abstract mixed-media paintings. A particular pair, entitled "Discussion with a Mitten" and "Discussion with a Paw," were brushed white and beige with coffee mugs glued to them — Warren MacKenzie's pottery, which Ballen had bought from a previous exhibition at the gallery. Molded black blobs at the bottom of each piece mimicked "Reflecting Pool." Ballen describes these experiments as "kind of like taking a painting and making it a table," where you lay out all the incidental elements of your past to sort through.

In August 2015, Susanne Hilberry passed away at age 72 from complications associated with a brain tumor. While nostalgia is usually one of Ballen's least favorite subjects for art-making, this exhibition had opened a little over a year after Hilberry's passing. "It was about looking back and looking forward," he says. "The show had all these points of collaboration with the gallery."

At the end of February, the gallery will close its doors, ending a four-decade run presenting both leading artists of the 20th and 21st centuries as well as emerging unknowns. That puts Hilberry in the company of this country's most venerable and pioneering dealers, such as New York's Mary Boone, Barbara Gladstone, or Paula Cooper.

You could call Ballen's exhibition a metaphor or an homage, but the truth isn't so basic. Ballen landed there because Hilberry was an intuitive visionary. "When I first moved to Detroit a decade ago and started grad school at Cranbrook, I saw an Alex Katz show at the gallery," Ballen says. "I remember thinking to myself, I will never show in a space this beautiful." Shortly thereafter, Hilberry visited his studio. The gallerist and her staff had been poking around Cranbrook's corridors during a late-night dance party and discovered his work.

It's easy to become myopic about the people and places that matter to a community. Maybe there's a Susanne Hilberry in Kansas City, Chicago, or St. Louis. New York Times writer and author Philip Gefter certainly has a sense of whether there's truth in that. "I loved Susanne," he says. "I often said about her: Who knew that the chic-est woman in New York lived in Detroit?"

A Devoted Life

Hilberry was a rare woman with agency and self-determination. She built the world around her. She was an imposing figure. If she liked you, it was incredible. If she didn't, you felt awful. And if you didn't know her well, she could seem inaccessible.

"Like a queen," says artist Scott Hocking. ("Scotland," she called him.) He exhibited at the gallery and worked there for 16 years, despite the fact that right around his first day on the job he accidently tore a huge hole through a $100,000 painting by one of her oldest and dearest friends, Ellen Phelan.

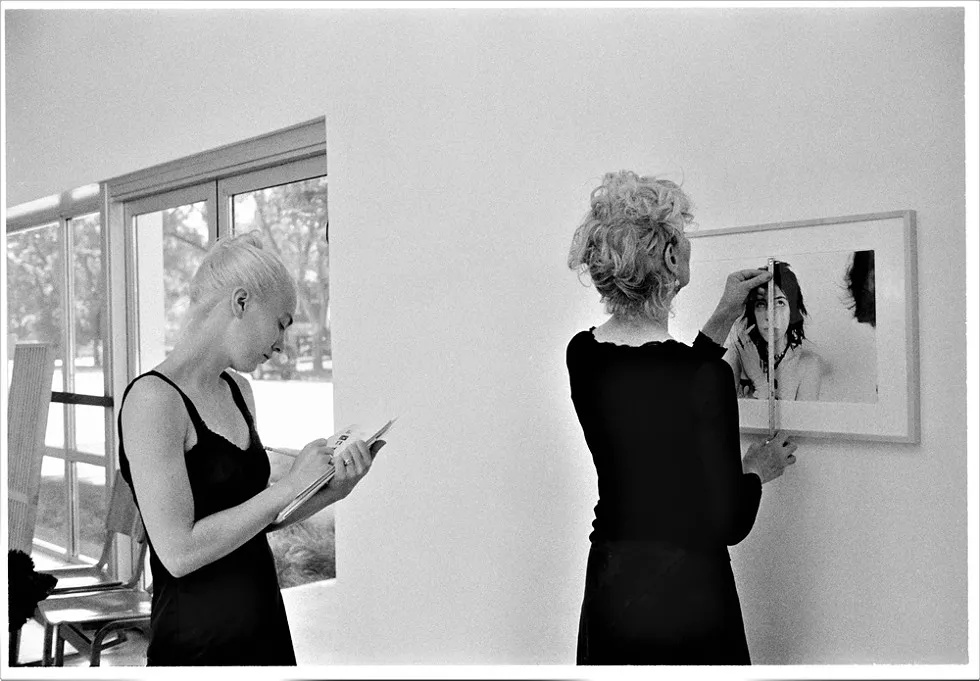

Hazel Blake, the gallery's longtime director, admits she almost didn't walk through the front door for an interview more than a decade ago. "I drove by in my husband's beaten pick-up and saw her sitting there, through the windows. I think I circled the block a few times before going in." It's a good thing Blake did walk in. The pair sat down on the couch and chatted. They both felt at ease so there wasn't any formal interview.

Hilberry was compelled to be around original spirits who feel comfortable in their own skin. The gallery is a formidable space, but within it you get a sense of the familial. The staff of Blake, Hocking, Sara Blakeman, and Angela Pham know the perfumes Hilberry wore — no more than four at once, comprised of a patchouli scent made by the Florentine monks of Santa Maria Novella, and accents of fig. "She would come out in this cloud of perfume and you'd have this experience like, where am I?" Blake recalls. "There's another mix we're not going to talk about. The Hilberry Gallery mix."

They all gave each other haircuts. Hocking introduced Hilberry to T. Rex, which she enjoyed as much as an Easter choral or silence. Every day the staff prepared "gallery lunch" together. The crew collaborated on exhibition invitations, either huddled around a computer, stenciling, stickering, stamping out a woodblock print or, for Hocking's first solo show, stuffing envelopes with caramel corn. Her own little cottage industry, as Hilberry called it.

She weighed in on their silly little dramas. "Susanne was a good listener," Blakeman says. "She would have these Yoda moments. I'd tell her something in the morning and before walking out at the end of the day, she might say, 'Sara, you know, I have this feeling ...'" She had an almost maudlin way of expressing herself. She was a voracious reader of novels and referred to all plants by their Latin name. Her intelligence could be incisive, which was part of what was intimidating — that, and a striking visage to rival any Gustav Klimt muse.

Hilberry was born on the south side of Chicago in 1943. Her father, David Feld, was a prominent obstetrician whom his daughter adored. Her warm and loving mother, Barbara, studied English literature and wrote poetry. Both parents were native Detroiters, so the family moved back to the city when she was 5. With her two younger brothers, they lived between 7 and 8 Mile Road, near Palmer Park, close to the posh "Avenue of Fashion."

Susie Feld, as she was known, went to Mumford High School on the near northwest side. After brief stints at University of California in Berkley and University of Michigan, she enrolled at Wayne State University, where she completed her undergraduate degree in art history. Later she received her master's degree in architectural history from Yale University.

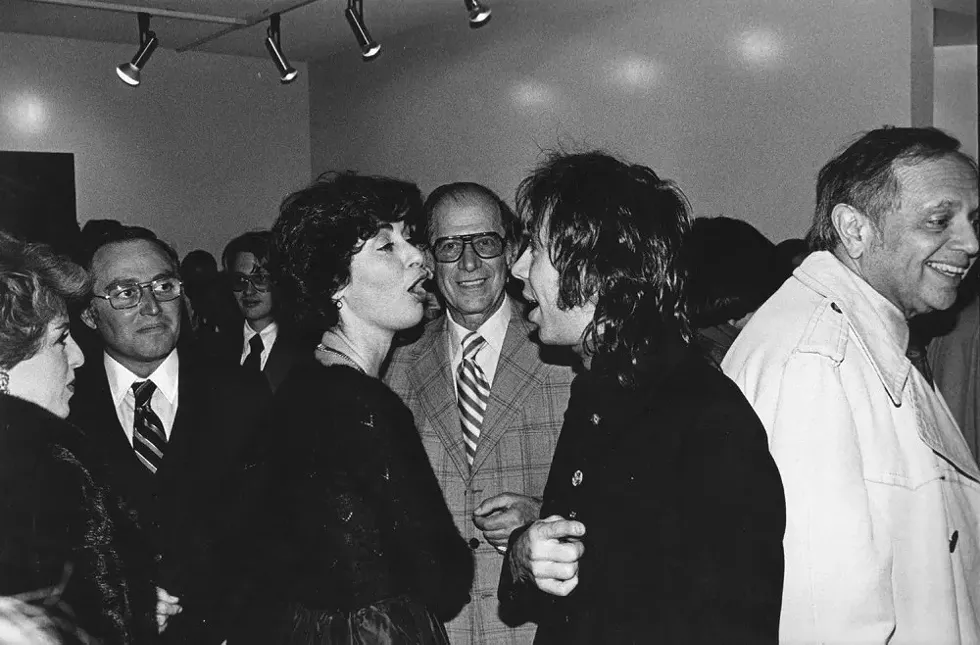

Her next move aligned her toward her destiny. "I wormed my way into working with Sam Wagstaff," she recounted in a 2010 interview with Aimee Ergas, then a Wayne State graduate student. As Curator of Contemporary Art at the Detroit Institute of Arts, Wagstaff was a dashing new force in town, a debonair intellectual from the East Coast, an elite with a wild side. He started at the DIA in 1968, following his time as a curator at the Wadsworth Atheneum in Hartford, Connecticut, where he produced a landmark exhibition on minimal art. For approximately three years, Hilberry worked under him as a junior curator, when she was just a twentysomething. His interest in Detroit's underground scene made an impression.

"Wagstaff brought the New York avant-garde to a conservative institution," writes Gefter in his biography Wagstaff: Before and After Mapplethorpe (Liveright, 2015). On the streets of Detroit, he uncovered art that had a lot to do with the minimalism, feminism, and radical performance he knew. He made himself equally at home inside the hallowed Grande Ballroom, Reverend C.L. Franklin's church, and Cobb's Corner bar. At the museum, alongside her mentor, Hilberry realized what had become accessible to her. Glancing back decades later, she told Ergas:

"There were exhibitions where people needed assistants, and friendships were formed as a result of that. Studios were offered in summertime if somebody was going someplace so you got a feeling about New York. It became a real dialogue. And that's what Sam did. Sam provided you with a dialogue with the world. And everybody else who came here, it was kind of — I'm being sloppy — but it was kind of academia. This was like people in the world, caring about something, being willing to devote their life to it. And you could talk to them. It didn't matter who they were."

In 1971, Wagstaff resigned from his position, following a fiasco with a 26-year-old artist he commissioned named Michael Heizer, whose transport and placement of a 30-ton block of granite dug a gargantuan divot in the DIA's front lawn. A DIA Annual Report documents that, in the absence of a curator, Hilberry coordinated most of the activities in the busy department, until a new lead curator was hired in 1974. This chapter in her life was pivotal because she met Cass Corridor artists and lifelong friends Ellen Phelan and Nancy Mitchnick, two painters who would eventually leave Detroit and become high-profile names in New York.

"I knew Susanne way before I even knew I could be a serious artist, and way before she knew she could be a big art dealer," says Mitchnick now. "My relationship with Susanne had a profound impact on my life. Susanne was a different person when we met her. Her clothes quoted the nineteenth century. She wore her hair up in a complicated circle. She was always wildly beautiful, but in the early '70s her vision came from literature. Susanne and (prominent Detroit art dealer) Ron Winokur and I read all of Henry James together, all of Virginia Woolf, as well as Lytton Strachey, and Leonard Woolf."

According to Mitchnick, after months of conversations with Phelan in particular, Hilberry opened her gallery in 1976, at age 31. Located in the basement of Birmingham's 555 building on Woodward Avenue, Hilberry's gallery showcased work by both Phelan and Mitchnick. Their growing reputations lent credibility to her project. At that time she also met sculptor Joel Shapiro, Phelan's husband, and they became close friends. Artist Valerie Parks, who has known Hilberry since then, says, "Susanne spoke to Joel every week. And when she was in the hospital for treatment later in life, he was her sweet and caring defender. Joel was a rock for her in many ways."

The gallery, of course, had precedents. From 1965 to 1977, Gerturde Kasle Gallery, located in the Fisher Building in New Center, presented stars of the abstract expressionist movement and introduced the region to a younger crowd. Jackie Feigenson did the same. From 1963 to 1974, the J.L. Hudson Gallery inside the downtown department store showcased Andy Warhol prints and sculpture by feminist artist Louise Nevelson. In addition to those commercial spaces bringing in the upper echelon, Hilberry's eye wandered to that Cass Corridor co-op, Willis Gallery. Charles McGee's Gallery 7 also set the bar high for its energy and dedication to talented locals.

For 25 years, in her Birmingham space, she showed art by top international figures, such as Donald Judd, Lee Krasner, Robert Rauschenberg, Willem De Kooning, Frank Stella, Claes Oldenburg, Louise Bourgeois, Roy Lichtenstein, Elizabeth Murray, Richard Tuttle, Lynda Benglis, and Judy Pfaff, among many others, and promoted such Detroit mainstays as Gordon Newton, Michael Luchs, and Cay Bahnmiller. But the staid environs became predictable. In 1994, Hilberry and George N'Namdi, another Birmingham-based dealer, set their eyes on Detroit's downtown, hatching a plan to relocate together.

"We ran into each other at a dry cleaners," N'Namdi recalls. "OJ was in his Bronco on the television screen. We decided to start looking around because we both believed in Detroit. So we met every Friday downtown for breakfast at Harmonie Garden (then in Harmonie Park). Her dogs came with us, those damn dogs, always in the backseat. I got to know her really well through that process."

N'Namdi was anxious to move. "You know how some people say 'location, location, location?' Susanne was always about aesthetics, aesthetics, aesthetics. I'd be impatient to close a deal and she'd be like, 'What color are the window frames?'"

He ended up going solo, settling on a building located on Forest Avenue, east of Woodward in Detroit's Cultural Center, to her chagrin. His gallery has since expanded into N'Namdi Center for the Arts. N'Namdi emphasizes they shared an understanding that art has the power to widen the consciousness of a community. "For me, it's about coming together," he says. "For her, it's the purity, the peace of mind. That's where she thrived. In the end, it was good the way it worked out. My place is always going to have my coat lying around somewhere. She wouldn't want that."

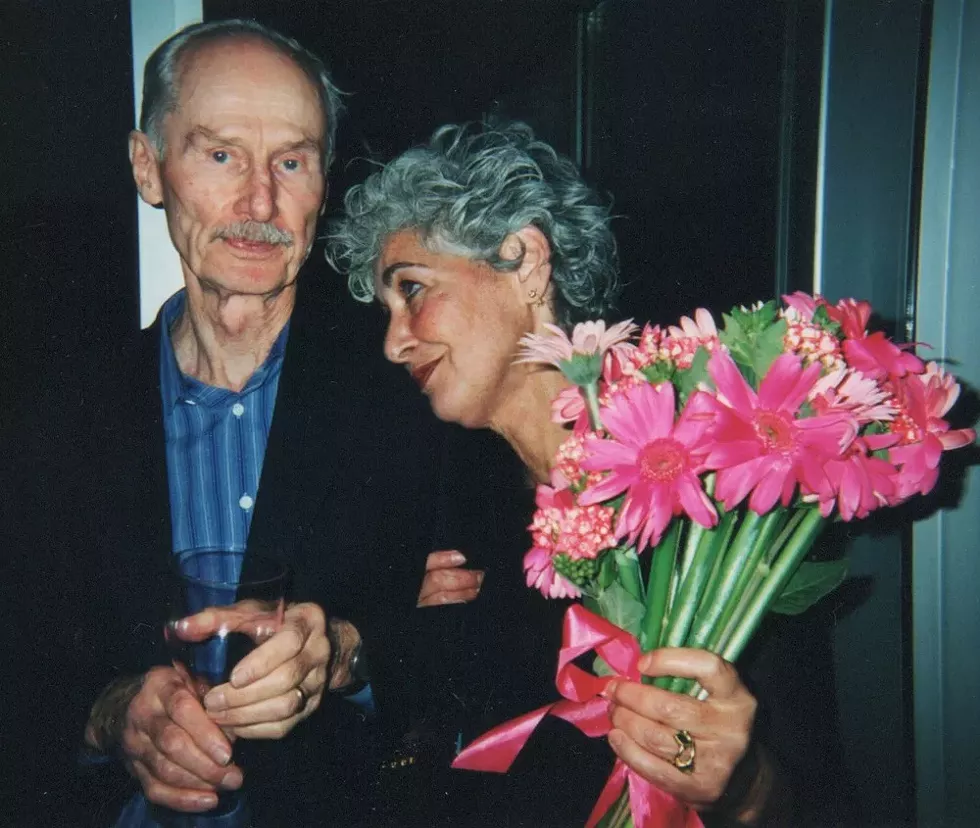

Hilberry continued searching for something that spoke to her. Guided by the counsel of her husband, Richard Kandarian, a successful businessman in the cutting tool business who she married in the late 1980s, Hilberry sought to invest in a property. On a quiet commercial-industrial strip, shaded by curbside trees and within two miles of where she grew up, she found a place to call home, almost literally. She once told former MT arts editor George Tysh that she might end up living there.

In 2000, the Birmingham location closed. The following year, renovations began at 700 Livernois in Ferndale, a modest single-story building circa 1955 and formerly occupied by Peterson Glass Company. Her passion for architecture returned as she worked with Birmingham architect Tamas von Staden to transform a 4,500-square-foot building — ordinary from drop ceiling to tiled floor — into a showroom with an aura glowing so bright it set a standard for the region as the bold, confident decision of a purist. The space is lit by a grid of inexpensive outdoor security lamps, sandblasted down to galvanized metal. The walls aren't painted; they're skimmed with uncoated plaster over cinderblock. These choices were made on the basis of authenticity and integrity. She made that building into its best self. The public was welcomed to that sleepy street in 2002 with solo exhibitions by both Phelan and American conceptualist Richard Artschwager.

Increasingly in the years to come, Hilberry introduced brave and heady young artists into her program. To name a few: Zak Prekop, who was a graduate of Frankfurt's esteemed Städelschule; Russian-born painter Elena Pankova; French artist Anna-Lise Coste; sculptor Shannon Goff, and Detroit native Michael E. Smith, who met Hilberry when he was still a student at College for Creative Studies.

"I screened a weird, long video at Motor City Brewing Works," Smith says. "I remember standing in the parking lot looking in, giddy and totally floored that Susanne Hilberry was in the bar watching the entire thing — and it was a tough piece in both content and duration." His first exhibition at the gallery came a couple years later, during his first two semesters in grad school at Yale.

Smith lives with his wife and two children in Providence, Rhode Island. He's just returned from Paris where he's featured in an exhibition at the Palais de Tokyo. The artist is represented by galleries in New York, Los Angeles, Berlin, and Milan and has been included in museum exhibitions nationally and overseas.

"My work is defensive," he explains. "I find myself being afraid most of the time. From the get-go, I was interested in challenging myself, so I'd get into the gallery two days before the opening, and nobody, including me, would have any idea what the work would look like. I would just deal with the fallout afterwards. With her, there was no pressure — and I was quite naïve at the time. But that's how I still work. If it wasn't for her, I don't think that process would have been able to fully develop. The fact that she paid such close attention meant that I could make very subtle moves. She would read every note I wrote to her. It was a slow, free-flowing relationship around ideas."

For the exhibition 39 Years, which coincided with Hilberry's memorial in 2015, Blake and her staff installed a captivating and challenging selection from the gallery's collection. Smith made a sculpture for that show with Hilberry in mind. "It's the closest I have ever come to a portrait," he says. "I found a really skinny door, and mounted it on a cow bell."

"I think perhaps the most interesting work doesn't look like " – Susanne Hilberry, 2010

Artist John Corbin attempts to summarize his experience looking at work with Hilberry, who wouldn't pontificate about art in theoretical or historical terms. "It took me a very long time to realize Susanne wasn't pretending when she would say to me, 'I don't have any idea what you are talking about.'"

"I would say something like, 'This work has a completely modernist sensibility,' and she would literally say to me 'I don't know what you mean.' I got a lot out of that. I make connections. For her it was this visceral thing."

The gallerist's point of view was informed by many years of looking; in New York, certainly, but also across the state, the Midwest, and overseas. Her family of artists (she hated the terms "stable" or "roster") was multigenerational and vast. She was invested in giving an artist their first solo show and in exhibiting less-popular work by a well-known name. Art on view ranged in price from $300 to $300,000. Layaway was always accepted. Even Blake and Blakeman bought work in $50 installments.

"The business side of art didn't equate for her," says Ivin Ballen. "It's easier to talk about what Susanne wasn't interested in. She wasn't interested in talking about 'sales.' It was more about getting someone to take the work home with them. That's how she would describe it — 'we found a home' for such and such piece. For her, there was a value to art but she didn't monetize it."

Hilberry engaged with art like one might see a lover. She would stare at something until it revealed itself to her (or didn't). She didn't care about trends and she was disappointed in people who couldn't get past what they are looking at, to see something more meaningful.

Ballen lives and works in Brooklyn now. "As an abstract painter, my work isn't very topical. Sadly, I have yet to find the support that she gave me. All the artists who show at Susanne's are the same people who show in New York, yet I can't even get a studio visit with those galleries. Different cities have different trends. One of the lessons I learned from Susanne is that she fell for what I was doing. There is a romantic element to that. I can't approach a gallery and convince them. They have to do it on their own."

A divine intervention — that's how Nancy Mitcnick characterizes a studio visit with her. "She loved painting. The intimacy of a studio visit meant the world to her. If she was moved by something she would weep. I thought all art dealers would be sublime. She was a hard act to follow."

Emphasizing Hilberry 's finely-honed instincts without any frills would be to tell you that she never used a level, that instrument used to hang art straight. While it could be maddening to some, she didn't trust the tool. She didn't believe it. She claimed to know when art was balanced at a deeper level because her own center was correct.

At Hilberry's memorial, John Corbin spoke to a large crowd squeezed inside the gallery. He gave a moving eulogy.

"There might be one or two of you here that didn't know Susanne for as long as you might have liked to. I can assure you that you will carry her with you in ways that you might not perceive," he said. "When you get up in the morning and put the same clothes on from the day before and look as smashing on Wednesday as you did on Tuesday, that's Susanne. When you change tables at a restaurant for the third time because the painting hanging over the banquet isn't anything that anyone should have to look at while eating, that's Susanne."

“When you get up in the morning and put the same clothes on from the day before and look as smashing on Wednesday as you did on Tuesday, that's Susanne.”

tweet this

Her legacy is also inscribed on a plaque recognizing the newly-named position of Susanne Feld Hilberry Senior Curator at Large, at the Museum of Contemporary Art Detroit (MOCAD), an institution that was the result of conversations starting in 1995 and lasting 11 years between several patrons and leaders in the art community. "Susanne felt the city needed a contemporary museum and asked me if I would work on it with her," says MOCAD founding director and board president Marsha Miro, a former newspaper critic and historian. "Because of her gallery, she then turned the project over to me. But she was always there coming up with ideas, helping me when there were roadblocks, suggesting the curator, or contributing funds ... She was active in so many ways." MOCAD opened its doors to the public in October 2006. The curatorial position, held by Jens Hoffmann, is supported by the Susanne Feld Hilberry Endowment for the Arts, which was created by the trustees of Hilberry's estate to support her interest in contemporary art.

During the interview with Ergas in 2010, Hilberry was asked about connections between today's art scene and the legacy of Cass Corridor artists. She paused before summating, "I just don't know if I'm a good person to ask. I don't see connections necessarily or very much in terms of actual visual vocabulary influence. It may be what I'm looking at. I mean it's obviously what I'm looking at. What you look at and what you don't look at. I'm sure there are people who are very influenced by Ellen's [Phelan] unbelievably able, exciting painting and the whole kind of modulation between abstraction and representation. Or the permission that Gordon [Newton] gave people to use certain kinds of materials."

As against generalities as she was absolutes, her reluctance to characterize her taste or to comment on the trajectory of contemporary art was in part an expression of noncomformity. "The smartest people that I know right now? You can be influenced by peoples' work, right? And it doesn't look anything like the work. When people say 'the Cass Corridor' and connections, often it seems to me what they mean is that there's somebody who kind of 'looks like,' and I think perhaps the most interesting work doesn't look like."

In the interview she continues, paying respect to the tenacious young artists of the 1960s and '70s who "evolved in public" and went through "both the excitement and the agony of putting work on view," staking their claim and making their voices heard by the establishment. She told Ergas, "I think the real belief that somebody would take you seriously in this community at that time was Sam, now this is me."

The Susanne Hilberry Gallery is located at 700 Livernois St., Ferndale; 248-541-4700; susannehilberrygallery.com. There are no further exhibitions, but staff will be on site through February.