Ojibwa artist Bonnie Devine tackles colonial expansion across Great Lakes in ‘Watershed’ exhibit

University of Michigan Museum of Art’s latest exhibit highlights Indigenous displacement and environmental issues relating to water

[

{

"name": "GPT - Leaderboard - Inline - Content",

"component": "35519556",

"insertPoint": "5th",

"startingPoint": "3",

"requiredCountToDisplay": "3",

"maxInsertions": 100

}

]

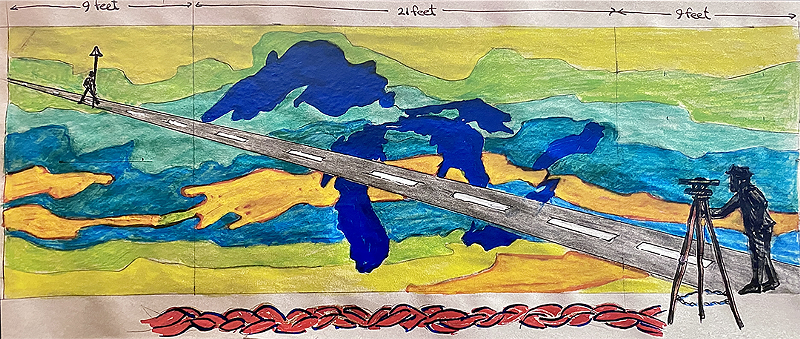

Ojibwa artist Bonnie Devine breathes life onto the walls as she paints a mural of the five lakes at the University of Michigan Museum of Art. Her paintbrush tells the story of Anishinaabe land that was violently stolen, with spiritual connections and a harmonious life with nature disrupted by colonization.

The Anishinaabe are the original inhabitants of the Great Lakes region, including Michigan and parts of Canada. Metro Detroit is Anishinaabe land.

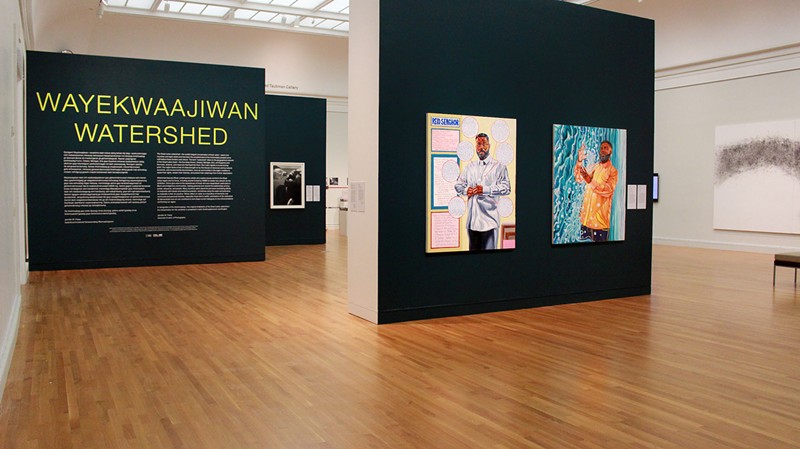

Devine’s mural, titled “The Gift, " is part of a new exhibit at the University of Michigan Museum of Art called Watershed. The historic and continued displacement of Anishinaabe people from their ancestral lands is a resonating theme of the exhibit, which is on display now until Oct. 23.

Visitors can watch Devine in action as she works on the mural in the museum space until its completion. The show also features work from 14 other international and local artists, ranging from sculpture, photography, and paintings exploring political and personal narratives surrounding the Great Lakes, while looking at water as a source of hope.

For the first time in the museum’s history, exhibit descriptions will be both in English and Anishinaabemowin, the Anishinaabe language.

Beyond simply a mural, Devine refers to “The Gift” as a portrait, since the lakes are considered the great givers of life in the Anishinaabe tradition.

“I was always taught that the lakes are conscious, animate beings that are radiating out this life, so the be able to paint that is great,” she tells Metro Times. “Actually, we were taught that everything is animate and nothing is above another thing. We are so interdependent and connected … I have drunk the water from those lakes all my life. The fish that we eat, the meat that we eat, the plants, everything is imbued with the water from those lakes.”

Devine is based in Toronto, where she grew up. Her family comes from the Serpent River First Nation reserve on the north shore of Lake Huron in Ontario. While the reservation is only about 14 miles long, Devine says the territory was much more expansive prior to the Robinson-Huron Treaty in 1850.

“We reckon our people have been there 10,000 or 12,000 years,” she says. “Our territory was an enormous woodland and now it’s a tiny sliver of land along the lake, so I’m aware of the incredibly potent economic loss that was to my family. It meant we went from being well-nourished, well-clothed, traveled people that had free access to all of the lands around them and all of the waters. We became impoverished after 1850, and still are facing economic impediments.”

She adds, “when we talk about what the United States or Canada or capitalists think of as wealth, and we talk about what Indigenous people think of as wealth, for us, wealth means health — being able to care of your family, being able to care for your community, having mobility being able to be exposed to various cultures and languages and all of that was taken away.”

Visually, “The Gift” is a map of the Great Lakes with a road cutting across the region to symbolize how it was divided to sell plots of land and create political strongholds where governments could establish sovereignty over the land.

“The road really is the most potent symbol that I could think of,” Devine says. “My initial thought was it’s going to be a highway ... and then I came across this beautiful pot of paint that is a stainless steel color. And as I was thinking this, it also became a pipeline. It becomes all those means by which goods, equipment, military interventions, all of those things that happened in straight lines in colonial times that completely disregard the contours of the land and the water.”

The mural will also feature two areas of handwritten text that honor the 1817 Treaty of Fort Meigs and memorialize Indigenous lives lost at government-run boarding schools in Michigan.

As part of the treaty, the Three Fires Confederacy (Ojibwe, Ottawa, and Potawatomi nations) agreed to give a parcel of land to the United States to establish a university in Michigan. The land parcel was originally located in Detroit, but was later transferred to Ann Arbor, where the University of Michigan now stands. The Three Fires Confederacy gifted the land under the condition that native people would be able to attend the university.

“Well, sadly that deal was not really ever honored until the 1970s,” Devine says. “And instead, of course, what the government did both in Canada and the United States was establish boarding schools that were specifically for native people to go to. They were certainly not universities. They were essentially training schools in order to develop a servant class for the colonials here. My mom went to one of those schools in Canada. Every member of that generation in my family was in a residential school in Canada.”

Before starting on the mural, she consecrated the space with tobacco to acknowledge the suffering her people have experienced over the last 400 years and to let her ancestors know their story is finally being told.

“When my parents were my age and younger, they did not have the opportunities I have,” she says. “The privilege of painting on a museum wall is an enormous thing. I put the tobacco down before I started painting to reach out to my parents and my grandparents to let them know this is where we are now. We are beginning to tell our stories and people seem to be interested in them. With respect to the government, things have not changed. [They] are bent on something other than social justice, and I think that is true not only for Indigenous people but for everybody except for a few elites.”

Detroit artist Senghor Reid also has two paintings in Watershed. In an introspective examination of his body’s relationship with water, Reid exhibits “Gray’s Anatomy IV.” The piece paints Reid as a sort of scientific specimen, with text bubbles that examine how water functions in specific areas of the body like the brain and other organs.

He gazes off in the distance while buttoning a shirt, seemingly unaware of the intricate streams flowing within him.

“We have so many issues regarding water access and it led me to begin researching water content in our bodies, specifically how much water each of our major organs contained,” he explains. “As I was journaling, I was thinking about my personal habits. If I’m not properly hydrated, how is my lymphatic system affected? How well is my brain functioning? Am I more prone to succumbing to fear when I’m dehydrated?"

His second painting, “This is my Desire,” makes its debut at Watershed. In this one, Reid is engulfed in Lake Michigan as he tries to control the water swirling around him.

“I’m actually trying to manifest my control of my body in a real-world sense,” he says about the piece. “I felt like doing this painting where I was literally trying to move water molecules with my mind.”

Reid says the Great Lakes are often used as inspiration and points of reference in his work. Connecting with these bodies of water by taking a pilgrimage and dipping his feet in the water is a common part of his creative process.

Watershed was curated by Jennifer Friess, who considers the show “a poignant lens through which to consider many complex issues of our time.”

“From widespread environmental disaster and the displacement of Indigenous communities, to contemporary water tragedies such as the one that continues to grip the town of Flint, the Great Lakes region is a microcosm of much more global discussions around resources,” she writes in a press release. “The incredible artists featured in Watershed examine the power of water and the ramifications of corporate and political wrongdoing while fostering critical dialogues about our environmental and cultural futures.”

The hope is that audiences walk away from Watershed with newfound knowledge and respect for this land’s original people — or, at the very least, an appreciation for this vital resource that sustains all life in the Great Lakes region.

The University of Michigan Museum of Art is located at 525 S. State St., Ann Arbor; umma.umich.edu. Watershed is up until Oct. 23 and admission is free.

Stay connected with Detroit Metro Times. Subscribe to our newsletters, and follow us on Google News, Apple News, Twitter, Facebook, Instagram, Reddit, or TikTok.