The RMS Titanic. The MS Estonia. The SS Edmund Fitzgerald. Boats that inspire songs, films, and make it into history books are, most often, the ones that meet their untimely demise, resting at the bottom of their respective seas, leaving people, dreams, destinations, and fine china in their wake. The other ships that make headlines are usually the ones that cruise the Caribbean with their all-you-can-eat buffets, which are usually the inevitable source of gastrointestinal outbreaks that plague their unsuspecting passengers.

Then there are boats that spent the majority of their seafaring years bringing joy to the masses, serving as a backdrop to precious memories, quietly historic moments, and so much dancing only to be docked for what feels like a lifetime, rusting, waiting, dreaming of their next voyage.

If you listen closely, these boats have a story to tell, and they're eager to tell it. In the case of Detroit's beloved ferries to the shuttered Boblo Island Amusement Park — sisters SS Columbia and Ste. Claire — it's more of a ferry tale without an ending.

Filmmaker Aaron Schillinger doesn't know why he set out to make a documentary about boats. He's not, like, a boat guy in the way that some guys identify as boat guys, and in order to dedicate six years to making a movie about the oldest surviving passenger steamboats in the country (both of which are out of commission, though in varying states of decommission), one should be a boat guy. For 38-year-old Schillinger, the journey of his debut feature film Boblo Boats: A Detroit Ferry Tale started where all good stories start: a boat psychic.

"I sometimes wonder that, too," Schillinger says when asked why he felt compelled to tell this story. "I mean, I spent over six years trapped in Boblo Land. And it's kind of insane because I live in Ferndale now, but I'm originally from Virginia, and I lived in New York City for 15 years.” It was in NYC that Schillinger met the executive director of an organization whose goal was to resurrect the Columbia, the second group to attempt to do so following a failed 15-year effort by the Steamer Columbia Foundation. “And she told me she knew a woman who could psychically communicate with a steamboat,” he says. “So, I was like, I gotta meet this lady.”

OK, but first — what in the hull are the Boblo boats and what is Boblo Island?

For Detroiters born after 1990, Boblo Island (actually named “Bois Blanc,” but like so many words around here, mispronounced by non-French speaking folks) and the ferry steamboats that transported people to and from the Ontario, Canada, attraction may not ring any bells aside from older family members waxing nostalgic, or through songs like 2018's "Boblo Boat" by Detroit rapper Royce da 5'9'' featuring J. Cole (a song Schillinger tried to license for the film but was too pricey). On the track, Royce encapsulates the Boblo experience, referring to the island as "the Black amusement park" and describes the parties on the way to the island as being the "livest." For those who lived it firsthand, though, Boblo Island was an accessible and affordable paradise right in Detroit's backyard.

Opened in 1898, Boblo Island was one of North America's earliest amusement parks that, for nearly 95 years, was the place to be. The ferries were tasked with transporting thousands of people to and from the 2.5 mile-long, half-mile-wide island where people could enjoy attractions like what is believed to be the second-largest dance hall in the world, flying swings, roller coasters, bumper boats, a zoo, a ferris wheel, a log ride, a pirate ship, and, according to an incredible 1992 promotional video aimed at "teens" released just a year before the amusement park shuttered, high divers, magic shows, antique car rides, and views from the Sky Tower (one of the only remaining structures, though no longer functional, and like the rest of the theme park, reclaimed by nature on an island now partially occupied by McMansions, a restaurant, and golf-carting residents).

Alright, back to Gloria Davis, the late, great boat psychic.

"So I called Gloria and she just charmed the pants off me, I mean, not literally," Schillinger says. "I was a little skeptical of whether she could talk to the boat or not, but that doesn't really matter because she feels it herself."

It was through Gloria that Schillinger learned of the dedicated restoration teams who were working against all odds to salvage both steamboats, both of which, at the time of Schillinger's introduction, had seen better days.

"My first thought was like, 'why don't you guys build a new boat?'” he says. “But then I started to understand how much it meant to these people. And it was almost like this last vestige of something that for Detroiters represents this bygone era, or better times, and people were trying to hold on to that."

Hold on they did — and have continued to do — not unlike stubborn zebra mussels clinging to the hull.

Though Gloria was Schillinger's warm and eccentric introduction to Boblo Land, as he refers to it, she was also the first of several living, breathing characters who are Christopher Guest-ian in their quirks but are also larger than life in their shared passion of all things Boblo. The documentary, despite its title being about boats, is more about the people who loved them.

There's Dr. Ron Kattoo, an ER surgeon, dedicated father, and husband who has overcome stage 4 bladder cancer and a brain tumor and who is the majority owner of Ste. Claire — and deserves his own reality show. Before Kattoo and his crew got their hands on the boat, it was previously owned by John Belko and his ex-wife Diane Evon, who, for nostalgia's sake and with the goal of opening a haunted "Nautical Nightmare” attraction, bought the 197-foot-long, 96-year-old boat for $20,000 on Sept. 11, 2001. Three months into owning it, they sunk a whopping $100,000 to repair the hull and, by the end of their ownership — and their dissolved marriage and subsequent nasty divorce — the pair had spent more than half a million dollars on restoration. (It is implied that the boat and the financial commitment to fixing it played a role in their split.) According to Schillinger, Belko had gotten the closest to restoring the boat to her original glory, though still really far from fully restored. Belko became obsessed with the boat, per Evon's commentary in the film, and ended up losing the Ste. Claire in the divorce. Evon, who was filmed on a couch covered in animal pelts, was relieved when Kattoo offered to buy the boat.

Then there's Kevin Mayer.

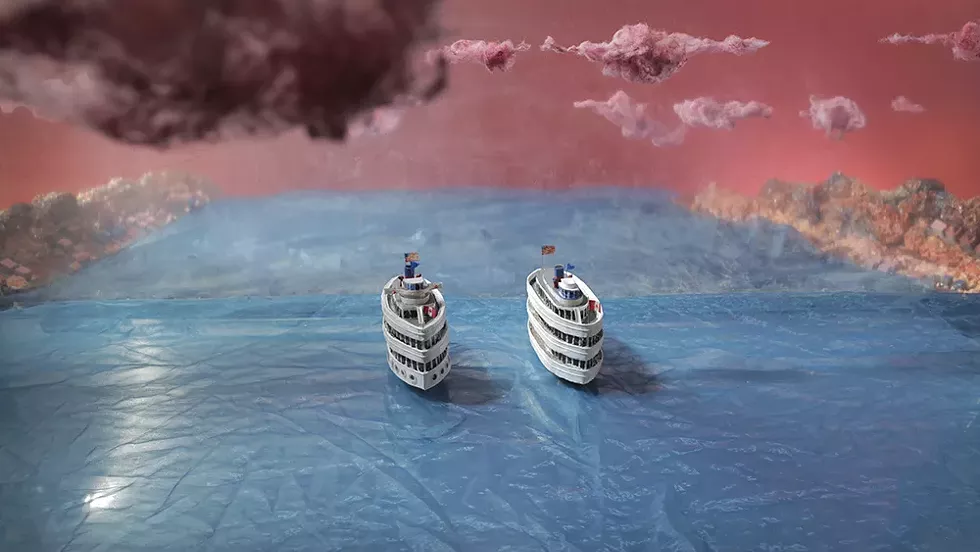

Mayer lives, breathes, and bleeds all things Boblo, which is why he quickly became Kattoo's right-hand man. He and his husband, who are featured prominently in the film with their collection of exotic birds and Boblo memorabilia, including actual rides (“The Bug” still functions) and attraction set pieces from the amusement park, as well as a moving, enchanting, and ever-evolving miniature model of Boblo Island Mayer has been putting together since 1989. (The model’s not a completely accurate recreation of the actual island, due to the fact that it has more rides than Boblo ever did. Mayer refers to it, optimistically, as his "future Boblo.") He proudly displays photos, life jackets, souvenirs, and his work uniform from when he worked at Boblo Island at a concession stand at 18 years old, and in many ways, Mayer is, in his mind, still 18, slinging hot dogs and Faygo soda. The closing of Boblo Island was somewhat traumatizing for Mayer, who Schillinger says is the unofficial heart of the film.

"For me, he's kind of the center of the story, because it affected him the most, emotionally," Schillinger says. "He was very easy to find. If you just start typing ‘Boblo’ into YouTube and scroll, eventually, you'll get to some interviews with him that local TV stations have done, coming out to film his mini amusement park. But nobody had spent a whole day with him to dig a little beneath the surface, because on the surface he's such a happy guy but… there's a sadness there."

Among the film's revolving door of characters is a mustachioed biologist; Dr. Kattoo's raven-haired wife and her brother, who takes over the day-to-day responsibilities of the boat's restoration; a member of the Detroit Historical Society; members of the community who wish Boblo would live again, and others who rather see change happen within Detroit's neighborhoods before investing funds into repairing a boat; and developer and self-made Seattle-based entrepreneur Michael Moodenbaugh.

Moodenbaugh bought the island — including the rides, pavilions, and an additional 100-acres — for $3.7 million in 1993, and had just 45 days to turn it around so that it could be profitable by the time it reopened for the season. He had previously been successful in reinvigorating a neglected Seattle-area water park and, with big-time investors like Jack and Larry Benaroya, Moodenbaugh's dream seemed like it could easily become a reality. And it did. For a flash, people had returned to the island in record numbers.

That is until Sept. 24 of that year, when Moodenbaugh was involved in a devastating car accident, in which he was placed in a drug-induced coma and was left paralyzed from the waist down. While recovering from his extensive injuries, his partnership with the investors soured and he learned that the Benaroyas had taken control of the island, put it into bankruptcy, fired all staff, sold off the rides, shut the park down, and sold the land. As Moodenbaugh states in the film, it is Boblo that "paid the price."

Perhaps the most magical figure in the film is that of the SS Columbia, which is anthropomorphized and voiced by Motown legend Martha Reeves. After all, what is a ferry tale without a little bit of magic?

“It was almost like this last vestige of something that for Detroiters represents this bygone era, or better times, and people were trying to hold on to that.”

tweet this

"Having the boat tell her own story was kind of my artistic way to get in there and tell it from a way that may be interesting to me," Schillinger says, adding that Martha and the Vandellas had performed on Boblo Island in the 1970s. "And I think that idea came to me after talking with Gloria, because she hears the boat speak. And I remember it was just like, I was staying in Monroe at a Red Roof Inn and there was a thunderstorm. I was there with my cinematographer Joel Flinders, and it just kind of clicked for me because I kept thinking, 'How can I make this documentary magical?' A magical narrator! Of course, have the boat talk! It was almost like common sense."

"When Boblo closed down, Claire and I fell into a deep slumber," Reeves narrates. "It seemed like even the Motor City itself was fast asleep. Shops closed their doors. The fires of the factory furnaces grew cold. The rivers slowed, even down to the fish, their fins frozen in time. And there we were, the oldest steamboats in America slumbering away, waiting for someone to come and wake us up."

Unlike the Ste. Claire, which is situated along the Detroit River, the SS Columbia was purchased by a New York-based nonprofit with lots of resources and contractors who hope to transform it into a traveling museum along the Hudson River. Reeve's narration, written by Schillinger, is both heartfelt and heartbreaking as Columbia speaks dotingly of its sister. It's like when an older sibling moves out and heads to college, leaving their brother or sister to fend for themselves against the tyranny of parents, authority, and growing up.

But the magic doesn't stop there, as woven in the tale of amusement park rides, dancing, and the efforts to preserve this special moment in Detroit history, Schillinger recruited production designer, puppet builder, and animator Bec Sloane to help tell another Boblo story, one rooted in the civil rights movement.

The documentary explores the life of Sarah Elizabeth Ray, referred to as "Detroit's other Rosa Parks," but whose story is rarely told despite playing a major role in moving the fight against segregation forward. Through beautiful and surreal stop motion puppetry, Schillinger retells the pivotal moment in which 24-year-old Ray made history while traveling on the Boblo boat in 1945 with her colleagues, all of whom were white; the boat, like most establishments at the time, was segregated.

Ray was removed from the Boblo boat and, though she had no choice but to obey, she took her complaint to the NAACP, which advised her to file a complaint with the State of Michigan. Per the Michigan Civil Rights Act, you could not discriminate on the basis of race on public accommodations. It was determined that what Ray experienced was a violation of that act. In a separate case that made its way to the United States Supreme Court, Boblo argued the state's equal-accommodation statute did not apply to its vessels because the island was technically in Canada. Lawyer Thurgood Marshall filed an amicus brief in support of the State of Michigan, and the court ruled in its favor.

"It gave Thurgood Marshall one more test of what was the Supreme Court's appetite for ruling that separate but equal in public accommodations and public spaces would be unconstitutional," author, activist, and former Metro Times editor and Free Press columnist Desiree Cooper says in the film. "So, his next trip to the Supreme Court was Brown v. Board of Education. So, for real, Sarah Elizabeth Ray did pave the way for the change of the law in the United States."

Ray, who dedicated her life to civil rights activism, died in 2006 at 88, as the film states, impoverished and alone.

"That's why we founded the Sarah E. Ray Project," Schillinger says of his and Cooper's partnership. "And it's one of my goals to use the film to help broaden her legacy and get her some more national recognition," he says. "It kind of changed a little bit when I was working on it in 2020 because of the Black Lives Matter movement. I already had the Sarah Elizabeth Ray element in there. But then I just realized, you know what, like, just having that isn't enough. … And so I wanted to participate in this re-education that America is doing about race and things that have been replaced by nostalgic whitewashing."

He continues, "You know, people like to tell you, 'Oh Boblo was always this place where all people could get along.' Well, no, it wasn't. But that's how all Detroiters kind of remember it. So again, that's where I'm trying to walk this tightrope of like, I want to acknowledge these civil rights heroes, while at the same time bringing back all those happy Boblo memories and playing into the nostalgia that is going to be the draw for probably most of the people who are going to come to the opening. They're coming because they have had Boblo memories. They don't know anything about the film. They're just like, Boblo, sign me up."

After launching the Sarah E. Ray Project, Schillinger and Cooper were able to remove her crumbling former home from Detroit land bank's demolition list and, instead, were able to designate it as one of "11 Most Endangered Historic Sites" in 2021. There are efforts underway in partnership with local nonprofits, volunteers, and the Charles H. Wright Museum of African American History, who plan on extracting the contents of the home. But, as is true with the restoration of the Boblo boats, time is of the essence.

Though the story of the Boblo Boats may seem tragic, especially when you consider the massive welding fire that ravaged the Ste. Claire in 2018 shortly after Kattoo and his team had finally found a place to dock the boat (a major hurdle explored in the film), and the fact that the SS Columbia has yet to serve its full potential, as intended, the overarching message is not one of gloom, doom, or lost history. Regardless of whether either ship ever sets sail again, the Boblo boats and the island are and forever will be uniquely Detroit — and thanks to the film, boat psychics, and the Kevin Mayers of the world, it will be a far harder task to forget Boblo than it will be to keep its memory alive.

You don't have to be a boat guy, gal, or gull to enjoy Schillinger's magical mystery boat ride of a film and, frankly, the documentary is even more fantastical if you aren't a former Boblo-goer. For Schillinger, the ride isn't over. He says he can't simply "drop" the people he met along the way now that filming is complete, and admits to becoming friends with some of the subjects, something he advises against but openly cherishes the opportunity to have been able to share their stories. But before moving on to new lands, he first has to debut the film in the city where it all started, and the city that will keep the story of Boblo moving toward the future.

"I just want to pay homage to all the people who have fond memories of the island and the boats, like it's really meant to be a love letter to Detroit," Schillinger says. "But I also do want the film to appeal to people who have no connection to Boblo who just love a good story with quirky characters who are striving to accomplish the impossible."

Boblo Boats: A Detroit Ferry Tale has its world premiere at 7 p.m. on Wednesday, Sep. 22 at the Freep Film Festival . See freepfilmfestival.com for more information. The film will also be screened at 8 p.m. on Saturday, Sept. 25 at The Chroma, 2937 E. Grand Blvd., Detroit; 313-446-8600; chromadetroit.city. Tickets are $12.

Updated Oct. 27: This story was edited to clarify that there was a previous effort to revive one of the Boblo boats, and also to clarify Thurgood Marhsall's role in a lawsuit against Boblo Island.

Stay connected with Detroit Metro Times. Subscribe to our newsletters, and follow us on Google News, Apple News, Twitter, Facebook, Instagram, or Reddit.