The trucks that rolled out of the Pfizer facility near Kalamazoo in December carrying the first batch of COVID-19 vaccines offered one of the first tangible symbols that this pandemic could eventually end, and like many people eager to survive it, I wanted to register to get one as soon as possible. I knew that frontline workers, the elderly, and the immunocompromised would be prioritized, and as a man in my 30s with no health conditions, I was prepared to wait a while. So I waited. Vaccination clinics started to become available through local health departments, as well as retail pharmacies like Meijer, CVS, and Rite Aid. Finally, as eligibility and availability expanded in early March, I registered for a vaccine from the health department for Oakland County, where I live, and through Meijer, which is down the street. I planned to just go with whichever one came through first.

Then — crickets. Nothing, not even a text back.

Meanwhile, it seemed like everyone I knew was already getting their vaccines. I started hearing stories about people who managed to get one just by being in the right place at the right time, scoring shots from pharmacies who needed to use up their doses before they expired, and then I began to hear more and more about impatient Michiganders who were traveling to Ohio, where vaccine access was far easier. I started feeling something I haven’t felt for more than a year — hello FOMO, my old friend — and considered registering at one more place. While Detroit has been running a drive-through vaccination clinic at TCF Center for city residents and workers, it wasn’t clear if I would be eligible, since I’ve mostly been working from home during the pandemic.

The timing couldn’t be any more urgent. Coronavirus cases in Michigan are soaring in recent weeks as part of a third surge that threatens to dwarf its previous two. Disturbingly, more than a year into the pandemic, Michigan is once again one of the top U.S. hotspots for the virus, with officials at the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention ranking the state with the highest number of COVID-19 cases per capita for the past seven days at 398.5 cases per 100,000 people, with New York City at 347.9 cases and New Jersey at 341.7 cases.

In a recent Zoom call with U.S. Rep. Andy Levin, Dr. Natasha Bagdasarian, a senior public health physician for Michigan Department of Health and Human Services, said she believed the latest Michigan surge is due to a “confluence of things all happening at the same time,” including a heavy presence of the B.1.1.7, a highly contagious mutation of the virus first discovered in the U.K. that has spread at the University of Michigan campus in Ann Arbor, the return of youth sports, and just plain old pandemic fatigue — all the people who have let their guard down because they’re tired of this, especially young people.

Finally, officials kicked things into high gear in March, opening a mass vaccination site at Detroit’s Ford Field. Run by the Federal Emergency Management Agency, along with help from the state, Meijer, Henry Ford Health System, the Detroit Lions, the City of Detroit, and Wayne County, officials say the facility has the capacity to vaccinate up to 6,000 people a day. That should help Michigan reach Gov. Gretchen Whitmer’s goal of achieving COVID-19 “herd immunity” by vaccinating at least 70% of the state’s population, or 5.6 million people. Hopefully then we can go back to some semblance of “normal.” So far, Michigan has fully vaccinated about 1.7 million people, or 20% of its residents, and about 2.85 million have received at least one dose, or about 30%. We still have a long way to go.

The Ford Field site started taking registrations from all Michigan residents on March 15, and I applied shortly after. Finally, on March 29, about a week after I registered, I got a text message prompting me to complete my registration, and got scheduled to get my first dose on Saturday. On Monday, the state expanded vaccination eligibility to all Michigan residents age 16 and older. Also on Monday, Detroit’s TCF Center began taking walk-ins, so things should start moving faster.

So far, Michigan has fully vaccinated about 1.7 million people, or 20% of its residents, and about 2.85 million have received at least one dose, or about 30%. We still have a long way to go.

tweet this

It turns out I wasn’t alone in feeling alone while I was waiting, however. In an absence of clarity on vaccinations, some people have taken matters into their own hands.

Earlier this year, Katie Monaghan was having a difficult time trying to get her father vaccinated when she noticed “Vaccine Hunter” pages on Facebook — grassroots communities where people banded together to share information. Noticing there wasn’t one for the Detroit area, Monaghan, an industrial and systems engineer by profession, created her own in February.

“Efficient processes is kind of what I do,” she tells Metro Times. The page directs to a simple Google Form that collects basic information from people — their name, address, and age — and inputs it into a spreadsheet. From there, a volunteer army of about 100 “Vaccine Angels” look up nearby vaccination clinics and make an appointment for the person, and then call the person back with the details. When the person has been helped, the Vaccine Angels remove their information from the spreadsheet.

Even after the opening of the Ford Field site, Monaghan says the “Detroit Area Vaccine Hunters - Michigan” page is as busy as ever, now boasting more than 17,300 members, with sister pages in western and northern Michigan. “We like to joke that we’re working ourselves out of a job,” she says.

Monaghan says the pages get more than 200 requests a day, including requests from people who don’t even know where to start, help for technologically impaired people navigating registration websites, or help linking people who don’t speak English with someone who can help them. Even though the elderly were one of the first groups to be eligible and have been prioritized for months, Monaghan says she’s surprised by how many people in that age group have still not gotten vaccinated and need help.

Still, Monaghan says that despite the dire situation (you know, people struggling to get vaccinated from a potentially deadly novel virus in a country that offers no universal health care for its citizens, unlike just about every other industrialized nation), morale on the page is high. “It’s probably the happiest place on the internet,” Monaghan says. “It’s just people helping people and sharing information to help everyone get vaccinated.”

Monaghan says that most of the volunteers have full-time jobs or families to take care of, and do this work pro bono. “Basically, we’re just spending every waking hour where we’re not taking care of other life responsibilities helping people on the list make vaccine appointments,” she says.

So far, the pages have helped more than 2,300 people make appointments, according to her spreadsheet.

“We don’t have any information that’s not out there that people can’t find themselves,” she admits. “It’s not like we have any secret ways around getting appointments. We just share information. … We don't have a magic wand or anything that we can wave to just get somebody a vaccine. It’s just about helping each other.”

Beyond making appointments for people, the page also provides crowdsourced answers to people’s questions. “I like to think we’re a pretty good partner for health departments because you might have a quick question — we’ve got 17,000 people that can answer it, probably,” she says. Plus, people can share their individual experiences that could be relevant to other people like them, like if they have a particular pre-existing condition, for instance, or help for people wary of crowds finding a clinic that might offer drive-through vaccinations. You might not be able to get that kind of help from waiting on a county health department or retail pharmacy phone hotline.

And even with the opening of the FEMA site at Ford Field, Monaghan says some people might not want to get vaccinated there.

“Ford Field is great and I know that they’re doing huge numbers, but not everyone — especially seniors and people with conditions or people who are working — is able to drive all the way there to get the vaccines,” she says.

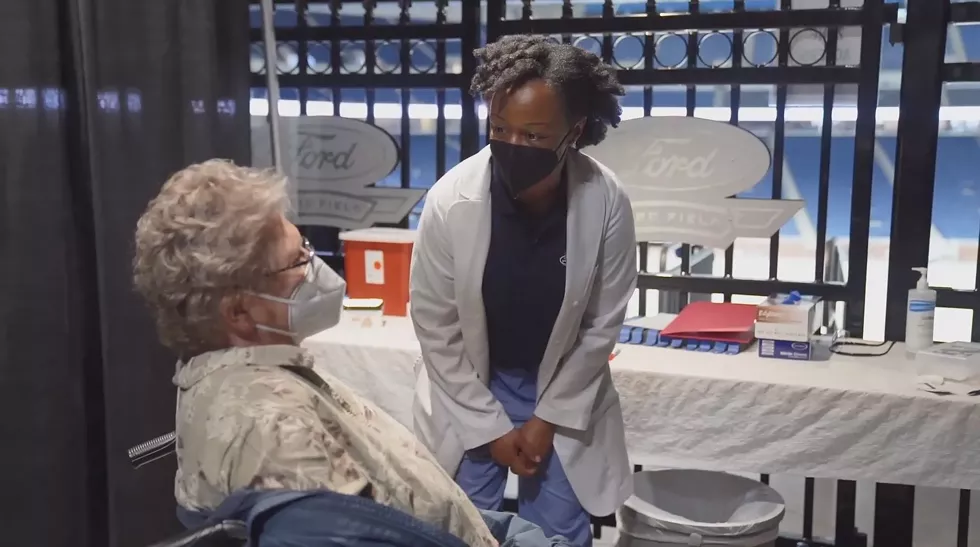

That said, in my experience Ford Field is an extremely smooth-running operation. If you’re trying to get a COVID-19 vaccine soon — and you should — this might be your best bet.

My appointment was on Saturday morning. Parking is free, and you can walk right in through the gate number on your registration confirmation email. Once inside, there are plenty of workers to help keep things moving while you wait in a winding line in the stadium’s concourse, following social-distancing markers on the ground.

While I waited, I read about how although the vaccines haven’t yet been approved by the Food and Drug Administration, they have been granted Emergency Use Authorization due to many clinical trials that have found them effective in preventing COVID-19. I also learned that they’re offering the made-in-Michigan Pfizer vaccines for the first six weeks of the program at Ford Field, which require two doses, and the single-dose Johnson & Johnson ones for the final two weeks. If you get the Pfizer vaccine, the second dose is taken a few weeks after your first. I was told I can expect a follow-up text to register for the second dose closer to the date.

When it’s your turn for a shot, you enter a numbered booth, where medical personnel from the U.S. Air Force administers the dose. I’m usually squeamish about needles, but I didn’t feel a thing.

From there, you’re directed to a waiting area where you sit for 15 minutes just to make sure you’re not one of the very, very rare cases of people who have had an allergic reaction to the vaccine. According to the CDC, there have been just five cases of severe allergic reaction per million doses associated with the Pfizer vaccine, and three cases per million doses for the Moderna one, mostly from people with a history of allergies. To date, the CDC has received 2,509 reports of death among people who have received the COVID-19 vaccine out of 145 million doses administered so far, though they say there is no evidence that the vaccinations contributed to the deaths. (To put that in perspective, more than 555,000 Americans have died of COVID-19.)

The whole thing — from parking to clearing the observation period — took me less than an hour.

I also scanned a provided QR code with my smartphone to sign up for v-safe, a CDC program that automatically checks in with you every day for a few weeks after the vaccination. Many people have reported feeling a bit sore on their arm where they got the shot, but I didn’t. The next morning, I felt the slightest of aches on my arm — as if my little brother punched me while playing “Slug Bug” on a childhood road trip or something. My second dose isn’t scheduled until about three weeks later, but I’ve heard many people say they felt fatigued for about a day after the second shot, so it might be best to just plan to take the day off if possible.

You also get a CDC-issued vaccination card with the date of your first dose printed on it. This could come in handy in case proof of vaccination is ever required, like it is for many other vaccines. They’re a little bigger than the typical wallet size, so keep it somewhere safe, like wherever you keep your passport or other important documents. You might have seen people post photos of their vaccination card on social media sites like Instagram, but experts advise not to do this, as it contains information like your name and date of birth that could potentially be used by creepers. I opted instead to post a selfie showing my Band-Aid, to hopefully remind and encourage my friends to make their own vaccination plan.

At this point, vaccine hesitancy, or people who don’t want to get vaccinated, could be the biggest hurdle left in fighting the pandemic. According to a recent U.S. Bureau Census survey, vaccine hesitancy in Michigan is higher than the national average, with 25% of Michiganders saying they “probably” or “definitely” won’t get vaccinated, compared to 17% of Americans 18 and older. According to the survey, hesitancy is most common among people 40-54 years old, with 35% saying they would not or are not likely to get the vaccine. The survey also found Black people are the demographic with the highest rate of vaccine hesitancy, with 35% saying they would not or aren’t likely to get vaccinated. A U-M survey found that number had declined to 25% in recent weeks, however.

Those divisions seem to show up in the data from people who have signed up to get vaccinated at Ford Field. Though Detroit’s population is nearly 80% Black, Black people make up just 13% of those vaccinated at Ford Field so far. The low rate extends to the city; according to state data, only about 19% of Detroit residents have received at least one dose of the vaccine, compared with 33% of residents statewide and 29% nationally. That’s a problem because the virus has disproportionately affected the city, with Detroit coronavirus deaths making up about 12% of the state’s total, and the virus killing 5.5% of people infected in Detroit compared to 2.4% in the state.

What you can do once you’re vaccinated

Fully vaccinated people can:• Visit with other fully vaccinated people indoors without wearing masks or physical distancing

• Visit with unvaccinated people from a single household who are at low risk for severe COVID-19 disease indoors without wearing masks or physical distancing

• Refrain from quarantine and testing following a known exposure if asymptomatic

• Resume domestic travel and refrain from testing before or after travel or self-quarantine after travel.

• Refrain from testing before leaving the United States for international travel (unless required by the destination) and refrain from self-quarantine after arriving back in the United States.

For now, fully vaccinated people should continue to:

• Take precautions in public like wearing a well-fitted mask and physical distancing

• Wear masks, practice physical distancing, and adhere to other prevention measures when visiting with unvaccinated people who are at increased risk for severe COVID-19 disease or who have an unvaccinated household member who is at increased risk for severe COVID-19 disease

• Wear masks, maintain physical distance, and practice other prevention measures when visiting with unvaccinated people from multiple households

• Avoid medium- and large-sized in-person gatherings

• Get tested if experiencing COVID-19 symptoms

• Follow guidance issued by individual employers

• Follow CDC and health department travel requirements and recommendations

Source: CDC

Lorie Turner, founder of God’s Path Community Services in Detroit, says she believes vaccine hesitancy in Detroit’s Black community is fueled by misinformation on social media, as well as barriers to access. Many people don’t watch or read mainstream media, she says, and while vaccinations have been offered at pharmacy chains like CVS or Meijer, many neighborhoods in Detroit don’t have them — in Detroit, for example, there are only two Meijer stores, and both are on the border of Oakland County. She thinks that the state should be partnering with everyone from social media influencers to longtime church leaders to help spread the word about vaccines.

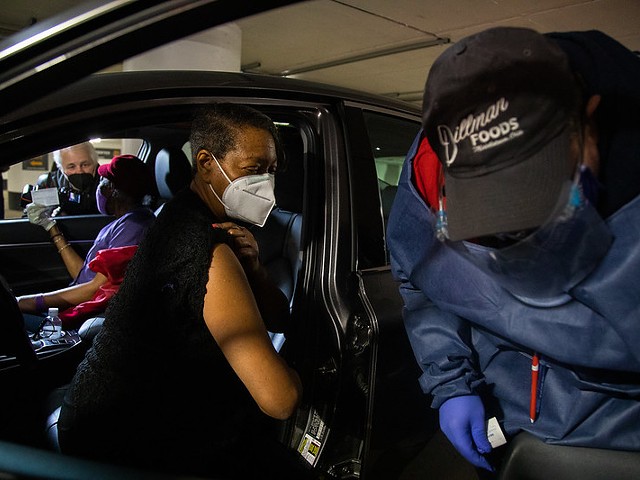

Earlier this year, Turner partnered with the Detroit health department to offer vaccine clinics at her church, Lemay Church of Christ, where she says she’s on track to vaccinate about 330 people in her community. “We should be getting that vaccine like everybody else,” she says. “If you can give it to Walmart and CVS, you can give it to us so we can help the community, as well.”

Turner says she hopes that more vaccines can become available for her church to do more clinics. “We had a big turnout of people to get that vaccine at this little church that has been here since 1916,” she says. “We need to meet people where they’re at.”

In that spirit, on Monday, Mayor Mike Duggan announced the opening of eight more vaccination sites in the city’s neighborhoods next week in hopes of getting residents to roll up their sleeves. The new sites will offer the one-dose Johnson & Johnson vaccine for one day at Henry Ford High School (Monday, April 12), Western High School (Monday, April 12), Philip Randolph Career and Technical School (Tuesday, April 13), Brenda Scott Academy (Wednesday, April 14), Cass Tech High School (Wednesday, April 14), Breithaupt Career Center (Thursday, April 15), Islamic Center of Detroit (Thursday, April 15), and East English Village Preparatory Academy (Friday, April 16).

There is another group that is associated with vaccine hesitancy. Another survey, by NPR/PBS News Hour/Marist, found that nearly half of Republican men, or 49%, say they won’t choose to be vaccinated. Among those who said they supported Donald Trump in 2020, 47% said they wouldn’t choose to be vaccinated, contrasted to about 6% of Democratic men and 10% of Biden supporters. And even before the COVID-19 pandemic and Trump, metro Detroit was identified as an anti-vaccination hotspot, with Wayne, Macomb, and Oakland counties included in a list of counties with the most unvaccinated kindergartners in a 2018 study by PLOS Medicine. Some states allow kindergartners to enroll without getting the required vaccinations on non-medical, or philosophical or religious grounds, including Michigan.

To that, I say it’s certainly your choice if you don’t want to get vaccinated. But one thing to remember is it’s really not about you — it’s about the safety of the larger community. I have never gotten vaccinated for the seasonal flu because I wasn’t personally worried about getting sick from it. But after this pandemic experience, I now understand that it’s not about my own risk — it’s about doing my small part to prevent an illness from spreading to more vulnerable people in my community. From now on, I’m going to start getting an annual flu shot. Similarly, getting vaccinated for COVID-19 is a small thing you can do to help end the pandemic.

Registering for vaccinations at Ford Field is easy. (Did I mention it’s also free, no health insurance necessary?) You can register online at clinic.meijer.com/register/CL2021, by calling the Michigan Department of Health and Human Services COVID-19 hotline at 888-535-6136 (and pressing 1), or by simply texting “ENDCOVID” to 75049.

The Ford Field site operates from 8 a.m. to 8:30 p.m., seven days a week. The program is running through mid-May, so you should register as soon as you can. I’m glad I did.

Stay on top of Detroit news and views. Sign up for our weekly issue newsletter delivered each Wednesday.