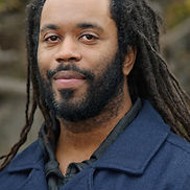

![Earlier this year, Montoya Givens was found dead in an abandoned Detroit-area building ]along with aspiring rappers Amani Kelly and Dante Wicker. - Courtesy photo](https://media2.metrotimes.com/metrotimes/imager/u/blog/33417956/received-918464116178445-copy.jpg?cb=1709161561)

Admittedly, she was eavesdropping.

Catina Fogle, 50, confesses that the mom in her was concerned about the movements of her adult son, Montoya Givens, whenever he left home. Givens had been released from prison just a few weeks short of a year and, though he seemed determined to stay on a positive track, Fogle kept as close of an eye on him as possible.

“He was loyal to the wrong people,” she says. “His loyalty was the best thing about him.”

Tragically, Fogle’s worries would prove well-founded: Givens, 31, was found dead in an abandoned Detroit-area building days later, along with aspiring rappers Amani (better known as “Armani”) Kelly, 27, and Dante Wicker, 31. The story of their Jan. 21 disappearance and triple-murder drew national attention and sparked significant social media buzz, including speculation by amateur sleuths. In five months authorities have announced no arrests connected to the killings, with Michigan State Police appealing to the public for help with their investigation back in mid-March.

As Fogle listened to Givens from nearby, she heard him debate with himself. She didn’t know much about the invitation her oldest son pondered, but she heard him say, at least, three times, “Naw, I’m not going.”

Then, moments later, he would change his mind again.

“Fuck it,” she heard Givens say. “I might as well go. I don’t have nothin’ else to do.”

Not long afterward, Givens received a phone call.

“What up doe?” he asked in popular Detroit-ese, meaning, “How you doin’?” or “What’s going on?”

Fogle’s translation from her son’s end of the chat let her know he was leaving his decision to fate. Givens told the caller he would go out with his girlfriend if the caller didn’t arrive to pick him up first.

Fogle wishes his girlfriend had come quicker.

Three roads traveled

It has been said that Givens, Kelly, and Wicker met in prison, but only Givens and Kelly served at the same facility from August 2017 to March 2022, according to Michigan Department of Corrections records. Kelly had been paroled barely six full months before his disappearance. Of the three men only Wicker had been home from prison for more than a year — since 2015, in fact.

Of the victims’ families and associates, only Fogle agreed to be interviewed by Metro Times.

Kelly, who released rap tracks under the names Marley Whoop and 37 Marley Whoop, apparently was the caller inviting Givens to attend a show at a storefront night spot that doubles as a hookah lounge on Detroit’s east side. In a Facebook video from what’s believed to be the night of the men’s disappearance Kelly tells two other young men there is “no solider dude” than Givens, and that he will be picking Givens up. The posting — while since removed from Kelly’s Facebook page, it has been “screenshot,” excerpted and dissected by social media users thousands of times — shows Kelly video-chatting with the unidentified men, all three of their faces concealed by ski masks.

Michigan State Police (MSP) have said the killings were gang-related and spokesman Lt. Mike Shaw says the investigation is active, declining an interview request. But most public speculation about motives for the killings has focused on Kelly and statements he makes during the video. His comments range from a monologue questioning those who fail to call out informants in prison to references to various men known by street names.

Kelly, who was paroled from Baraga Correctional Facility after serving seven years for armed robbery, was described as artistic and creative.

“Dreaming did not escape Armani,” reads an online obituary posted before Kelly’s Feb. 26 memorial. “He worked hard and had a strong desire of becoming a famous rap artist.”

“A natural comedian, he was always able to make people laugh,” states the tribute. “Armani had a heart of gold and would give the shirt off his back to help someone in need…He believed there is good in everyone, and he never met a stranger.”

After his release from Baraga, Kelly enrolled at Alpena Community College and worked for Cooper Standard, an automotive supplier, according to the obituary. He lived with his mother and stepfather in Oscoda, a town of fewer than 1,000 residents, three hours north of Detroit, and certainly not a hotbed for rappers.

But Kelly, it seems, got around, and whether they were in Oscoda, Detroit, or parts in between, he spoke of having enemies, real or perceived.

“Bitch, I’m back!” he raps on a Spotify track from the HardRoad EP. “No more state blues, back to drippin’, back to niggas sayin’ they gon’ kill me!”

Though aggressive in tone, the lyrics of “I’m Back” are, otherwise, no more provocative than those of countless other rap songs, and probably wouldn’t raise an eyebrow if not for Kelly’s tragic fate.

Wicker, of whom less seems publicly known, and who appears to have no social media profile of significance, was said to rap using the stage name “B12.” He pleaded guilty to armed robbery and felony firearm in 2011 but, like Kelly, loved ones say Wicker was much more than his criminal record suggests.

“My brother was a great boyfriend, amazing son, super uncle, and the best brother you could ask for,” reads a GoFundMe campaign page, launched by Chris Coleman, identified as Wicker’s “God brother.”

One of two GoFundMe efforts to raise money for Wicker’s burial, Coleman’s appeal adds, “I don’t care how you personally feel about him. Think of his mother and the woman he chose as his own. Help them sleep better. Please and thanks.”

A resident of Melvindale, Wicker’s name wasn’t familiar to police, according to a media report early in the murder investigation.

Givens’s name, on the other hand, was familiar to both the media and Detroit Police because of the high-profile carjacking and robbery of which he was convicted in 2012: The victim was Marvin Winans, Detroit pastor and member of the renowned family gospel group, The Winans. Givens, who was 19 at the time of the crime, pleaded guilty along with Christopher Moorehead and Brian Young in connection with the incident, during which the pastor’s SUV, Rolex watch, and $250 were taken.

Fogle vividly remembers the phone call she received from Givens, following the carjacking at a gas station. Her son was hiding in the closet of a house, Fogle says, and telling her that cops were closing in on him. He was about to flee, Givens told her.

“I said, ‘Son, please don’t run. If you run they’re going to kill you,’” recalls Fogle.

When their phone call ended Givens stepped out of the closet and turned himself in. It would be 10 years before Fogle saw him outside a courtroom or an inmate’s visiting area.

Prescient premonition

Though petite and youthful in appearance, Fogle had turned 50 on Jan. 19, two days before “Monty,” as Givens was called by relatives, went missing. He had struggled to find work since his release from Baraga, his mother says, as factory jobs in outlying areas of Detroit where the bus line was restricted were tough for him to keep.

Givens presented Fogle with a $10 pair of earbuds as a birthday gift, saying that he wished he could do more.

“It ain’t much,” he told her.

“That’s OK, son,” she said. “It’s the thought that counts.”

Givens smiled in response.

When he didn’t call to check on her, days after leaving home Jan. 21, Fogle knew something was wrong.

Until the lure of the streets captured him as a teenager, Givens helped raise four younger siblings while Fogle, a single parent, worked and went to school. Even during periods of homelessness when she says they all slept “on the street, in the snow,” or snuck onto strangers’ porches at night, Givens had been a dependable, young lieutenant.

At one point, the family survived by selling candy, a side hustle that eventually blossomed into an enterprise netting about $350 a day.

“God was so good to me that that one thought turned into a business for 10 years,” adds Fogle.

It was only when college professors found her need to bring Givens and the other children to classes with her too inconvenient that she began leaving him in charge of the family.

“I wanted my kids to understand: No matter what it is you go through, don’t give up on what you’re doing,” says Fogle.

So, despite obstacles in stability after 10 years in prison, Fogle says Givens was still making an effort. His brother produced music, but unlike Kelly and Wicker, Givens turned down the opportunity to rap, saying he’d rather find steady employment, notes Fogle.

She says “Marley” was a name Givens mentioned when referring to friends and associates, but she’d not heard of Wicker until the trio went missing. Her last glimpse of her son was when he walked out to the vehicle reportedly driven by Kelly. There were already two other passengers, possibly three, Fogle says, not sure if one of them participated in the crime that took her son’s life.

By the time she heard from two detectives after filing a missing person’s report, Fogle says she’d had a vision of three figures in a basement “under something.” She told the investigators about it.

“They both looked at each other in such awe...” she says. “After I told them that, that’s when they told me that he was buried under some rubble, or ‘debris’ as they called it.”

Givens’s body was discovered along with those of Wicker and Kelly, all reportedly frozen. They had been shot to death.

Clues and communication

A common pastime of inmates is chatting about what happens outside prison gates. Particularly among men and women who’ve walked the same halls or maybe even shared cells with parolees like Wicker, Kelly, and Givens, there tends to be a sense of connection and interest.

In prisons as far away as Saginaw Correctional, about 100 miles from Detroit in Freeland, inmates discussed the three bodies found in “the Pilla,” a nickname for the city of Highland Park.

“Don’t go down there” reportedly had been the warning on the street, apparently referencing Kelly’s distance from Oscoda to the Detroit area, but speculation about who was the main target abounds months later.

“If you exclude domestics and robberies, murder is also a form of communication. So somebody was talking to somebody,” says Ellis Stafford, a retired MSP inspector.

While MSP has offered no recent updates, Stafford says details about the crime reveal information that should result in it being solved.

The men were probably killed at a different location than where their bodies were found, he says.

“I don’t see a reason to go to a non-heated building in winter time,” Stafford adds. “There’s nothing there, but a rat-infested building, so why would you go there? You wouldn’t.”

There’s also the potential that the bodies would be discovered more quickly if left at the initial murder scene, Stafford says, as opposed to transporting them elsewhere.

Based on statistics and experience, he doubts the men were killed one at a time, and says there was likely a “flash to bang” scenario — meaning that there was an emotional spark or escalation that preceded the actual killings.

In order to get into the “social space” of Givens, Wicker, and Kelly, there were probably multiple killers, at least one of whom was known to one or more of the victims, Stafford says: “You know how hard it is to kill three people by one person? You’re not going to get three grown men, all of good, fighting age, in a place by yourself.”

The greater likelihood of someone escaping or struggling with a single shooter and possibly surviving the attack also points to multiple suspects, he says.

Vast attention to Kelly’s Facebook page and his social media comments as factors in the crime might also be valid, as followers of the case have suspected, adds Stafford.

“Absolutely,” he says, “tons of beefs start on social media.”

he adds, “Remember: What we’re dealing with is a code of the streets. It’s a mindset that says, ‘My reputation is worth more to me than my life itself.’”

Statistically, a majority of people will spend most of their daily lives within a 10-mile circle, whether going to convenience stores, a friend’s house, or wherever their frequent destinations might be, says Stafford, adding that, at least, one suspect likely crossed paths with a victim engaged in his usual routine.

“They knew the person they went with” when they disappeared, Stafford says.

Fogle hears lots of rumors about who is behind the murders, but she has gathered much more from street sources than from police. Due to ongoing personal and health challenges, she says she hasn’t had time to properly grieve Givens’s death. But just as he was punished for victimizing Winans, Fogle says it’s only fair that Givens be remembered as a victim who didn’t have a chance to complete his redemption.

“The main message I want out of this whole thing is, ‘Stop judging people by their past,’” she says. “Judge them by where they are.”

Subscribe to Metro Times newsletters.

Follow us: Google News | NewsBreak | Reddit | Instagram | Facebook | Twitter