The plan, early on, was to hide the letters in the church. The tight recesses at the ends of the pews or the dusty corner of the room would provide ample cover for a folded slip of paper. Everyone at church, directing their attention to casual conversations and prayer, would be too busy to notice. Only the writer and the recipient would be aware of the letters' existence.

Moving into digital communication would be challenging. Emails left a digital trail. And there was a larger concern with emails — adults could access emails, especially when those adults are parents to an 11-year-old boy. And if they did get access, secrets would be exposed and explanations would be in order.

So the letter writer and his recipient created a complex code in their emails, a safeguard for future conversations and a way to expand upon the letters exchanged within the walls of the church.

But in spite of all these protective measures that Patrick McAlvey went through as a young boy, all in hopes of curing himself of his homosexuality, he did not feel helpless at first.

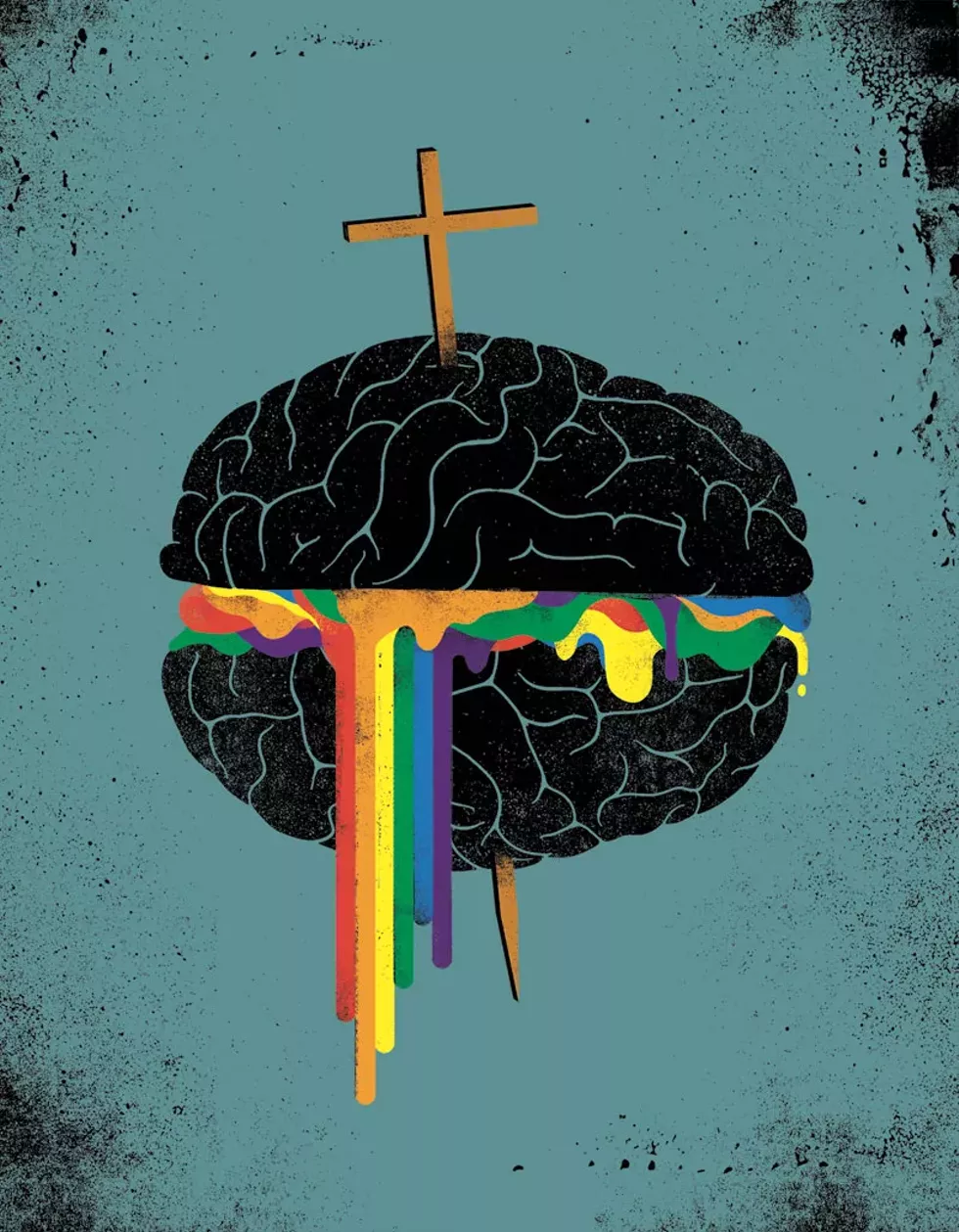

Patrick already knew he was a sinner; he had been having thoughts of "same-sex attraction," and the church community that he was raised in had always made it a point to condemn homosexuality. Same-sex attraction, he was told over and over again, was wrong, sinful, and unnatural.

But he was also told he could be changed. At the same time that the church espoused the evils of homosexuality, it also offered a path for salvation. God could change you. God could cure you. And if God ever needed any assistance, there was always Mike Jones.

Jones was a member of University Reformed Church, the East Lansing church that McAlvey once attended. He was respected and well-liked. But Mike Jones also billed himself as an expert in a practice known as conversion therapy — the pseudoscientific practice that attempts to convert a person's sexual orientation to heterosexual.

Patrick was 11 years old when he first reached out to Jones to fix the thoughts of same-sex attraction that had been flooding his mind. The clandestine system of communication they established — the tucked-away letters in the church, the coded emails — began a therapist-patient relationship that would stretch more than nine years.

Their relationship was centered on converting Patrick by reminding him of the evils of homosexuality, and by reinforcing that, with some counseling, he could rid himself of it.

"The worst part about what he did to me at that young age was to really reinforce and teach me that it is bad to be gay," McAlvey, now 33, says. "That everyone who is gay is addicted to drugs and alcohol and random sex. That none of them are happy. That a lot of them die of AIDS. But he also told me that change was both possible and necessary, and that I could and should change."

Little by little, the letters and emails grew more frequent. Soon, Jones was providing Patrick with resources and books that further emphasized that homosexuality was sinful and demonic. Though their relationship began as one more impersonal and distant because of Patrick's young age, it grew more intimate as Patrick became older and felt even more helpless and defeated in his struggle to change his sexual orientation.

"For nine or 10 years, just changing myself became the focus of my life," Patrick says. "And really as time passed and I didn't change, I learned to hate myself because I felt that there's this thing about me that is bad and that I can change it, other people can change it, and if I can't change it, it must be because I have not tried hard enough or I am not faithful enough to God."

McAlvey left Michigan and Jones behind after he completed high school for a missionary training school in Philadelphia. But he was kicked out in less than a year after he had disclosed that he struggled with what he called same-gender attraction.

Now even more lost and more desperate to "cure" himself, McAlvey returned home and contacted Jones once more to finally fix him. It was when he returned home that he met with Jones more intensively, several times a week for often the entirety of the day, over the course of four months.

"That's when a lot of the weirder stuff happened," he says.

Jones would allegedly implore McAlvey to confront his sexuality with graphic images and probing questioning. He had to describe his penis, his pubic hair, and his sexual fantasies in detail to him. He played a movie that had full-frontal male nudity. One day, Jones told Patrick that they would try something that he called holding therapy, in which Patrick lay in Jones' arms for an hour, locking eyes with him and smelling his body.

"I felt I had no choice but to — he had a lot of power over me," McAlvey remembers. "I felt like I had to do whatever he said because I was so desperate to change and he was the one who knew how to change me."

In 1935, an American mother wrote to Sigmund Freud, the father of psychoanalysis, asking him to treat her son's homosexuality. In a letter that would later become famous, Freud wrote back:

"I gather from your letter that your son is a homosexual. ... It is nothing to be ashamed of, no vice, no degradation; it cannot be classified as an illness; we consider it to be a variation of the sexual function, produced by a certain arrest of sexual development. ... By asking me if I can help [your son], you mean, I suppose, if I can abolish homosexuality and make normal heterosexuality take its place. The answer is, in a general way we cannot promise to achieve it."

Though Freud questioned the ethics behind conversion therapy in the letters, his theories on homosexuality were more complex. Both opponents and proponents of conversion therapy would cite Freud as justification for their beliefs well into the 19th century.

After Freud's death in 1939, however, many psychoanalysts diverted from the Freudian view of a normalized homosexuality and instead adopted views based on the work of Sandor Rado, a Hungarian psychoanalyst who believed that homosexuality was unnatural and a consequence of inadequate parenting. This new school believed homosexuality not only to be unnatural, but also mutable.

This group of psychoanalysts published studies that concluded that changing an individual's sexual orientation was possible. The studies provided an intellectual backdrop for the aggressive conversion therapy experiments performed on homosexuals in the period between Freud's death and the Stonewall Riots in 1969. Experiments ranged from electroshock therapy to "aversion therapy" in which LGTBQ people were given vomit-inducing chemicals when they looked at their lovers. Conversion therapy was widely accepted in the medical, academic, and social world. Time magazine even published a 1965 article titled "Homosexuals Can Be Cured" that praised a group therapy session of homosexuals led by psychiatrist Samuel Hadden.

But the Stonewall Riots and the ensuing LGBTQ rights movement in the decades to follow chipped away at the acceptance of conversion therapy. In 1973, the American Psychiatric Association removed homosexuality from its manual on mental disorders. A flurry of influential studies into the 21st century dismantled the case for conversion therapy.

In many respects, the gay rights movement that started at Stonewall has been successful in its crusade against conversion therapy. The practice is now universally understood to be pseudoscience and damaging to mental health by health care professionals, gay rights groups, and politicians alike. The APA now states its opposition to conversion therapy more forcefully, saying, "The potential risks of reparative therapy are great." The former United States Surgeon General David Satcher in 2001 issued a statement that "there is no valid scientific evidence that sexual orientation can be changed." And after the 2015 suicide of Leelah Acorn, a 17-year-old transgender teen who had undergone conversion therapy, the Obama administration spoke out against the practice. "As part of our dedication to protecting America's youth, this administration supports efforts to ban the use of conversion therapy for minors," wrote Valerie Jarrett, a senior adviser to President Barack Obama.

Even in many Christian groups, historically among the strongest supporters of conversion therapy, the tide seemed to be turning. After spending $600,000 on pro-conversion therapy ads in The New York Times, USA Today, and other publications as part of a 1998 campaign that Robert Knight of the Family Research Council referred to as the "Normandy landing in the culture war," Christian support for the practice withered. There was no longer new science to provide the empirical backdrop for the therapy. Just as the APA had done in 2000, other large medical organizations had forcefully come out against conversion therapy, debunking it as pseudoscience that was detrimental to one's mental health.

In the 2000s, high-profile Christian leaders of the movement had also come out themselves or had been exposed as gay. John Paulk, who had been a vocal advocate of conversion therapy on behalf of Exodus International, the now-defunct, influential, pro-conversion therapy organization, was photographed at a gay bar in 2000. Ted Haggard, the former president of the National Association of Evangelicals who unsuccessfully attempted to convert himself, was revealed in 2006 to have hired a male prostitute on numerous occasions.

A surprise announcement from Alan Chambers, the president of Exodus International, seemed to signal the end of the Christian pro-conversion therapy movement. At the organization's 38th annual conference, Chambers, who for years was a leading ex-gay voice in the country, announced that he no longer believed that sexual orientation could be changed.

"I am sorry for the pain and hurt many of you have experienced," Chambers wrote in a letter at the time. "I am sorry that some of you spent years working through the shame and guilt you felt when your attractions didn't change. I am sorry we promoted sexual orientation change efforts and reparative theories about sexual orientation that stigmatized parents." Conversion therapy in the 21st century appeared to be on its last legs.