America is a lot of things to a lot of different people. To some, it represents life, liberty, the pursuit of happiness — all of that groovy stuff. To others, it’s a dream deferred. Artists have always had a lot to say about our country because our right to free speech welcomes the expression of these different views. It’s easy to forget, though, that not all countries afford their citizens that right. To celebrate the Fourth of July, we decided to take a tour of different views of America by looking to Detroit’s street art, graffiti, and murals. What we found was both celebratory and critical, solemn and silly. Clearly, we, as Americans, have the ability to make America whatever we want it to be.

“Mano de Obra Campesina (Hand of the Peasant Labor)”

Dasic Fernandez

Located on the west wall of Hacienda Mexican Foods at 6022 W. Vernor Hwy., just east of Livernois Avenue

This impressive mural by Chilean painter Dasic Fernandez might not scream “red, white, and blue,” but it’s certainly every bit as American as any of the other murals on these pages. The towering farmer — who could very well be a migrant worker from Mexico — is harvesting corn, a crop native to the Americas. His giant, outstretched fingers looks like they’re worked to the bone, yet the wedding ring and the look of both hope and satisfaction on his face suggests he’s happy. While we couldn’t reach Hacienda Mexican Foods or the artist, it seems safe to say that the mural celebrates the idea of the American promise, the freedom to work hard and be able to provide for your loved ones.

This work, painted several years ago, wasn’t the only mural Fernandez was commissioned to paint with a sense of national pride in Detroit; last year he returned to paint Yemeni-themed murals in Hamtramck to celebrate that community’s presence.

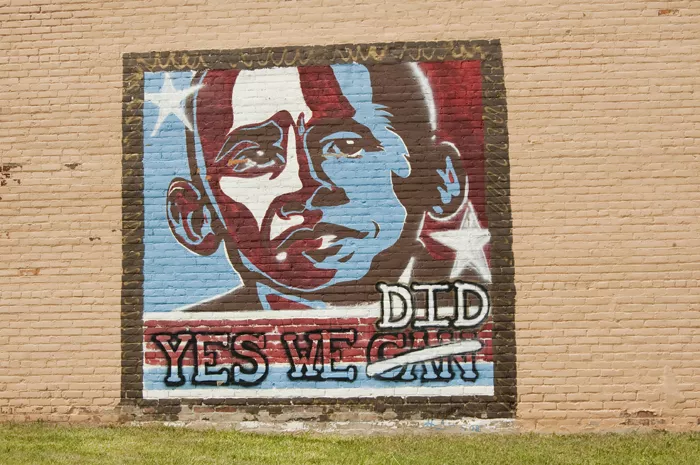

“Yes We Did”

Halima Cassell

Located on the south wall of Eric’s I’ve Been Framed at 16527 Livernois Rd., Detroit

In 2008, street artist Shepard Fairey designed the Obama “hope” poster, whose colors and style made it an instant icon. It became a work of true folk art, getting widely imitated during the campaign season, an example of the democratic powers of art, as well as the ability of art to mobilize and inspire. Eric Vaughn, shop owner of Eric’s I’ve Been Framed in Detroit, commissioned this copycat painting from local mural artist Halima Cassell to show his support for Obama during that first campaign. The slogan “yes we can” was updated once Obama won the election to read, “yes we did,” and the mural has remained through Obama’s second term to show solidarity with the president.

Cassell has held an art show at Eric’s shop since then. Today, she works with youth on outdoor artwork, with plans to transform a stretch of Oakland Avenue in Detroit’s North End neighborhood into an entire mile of community art.

“Tribute to Matty Moroun”

Marms and Skip

Near Recycle Here, 1331 Holden St., Detroit

A bald guy in a suit who looks like he could be a youthful version of Rich Uncle Pennybags (the guy from the Monopoly game) points at some coins floating in the sky. Dollar bills, stacks of gold bricks, and a bag of money can be found elsewhere in the scene, while a disembodied eagle talon clutches a diamond, draped by a banner that reads “RICH 4EVER.” The only depiction of the “American dream” more garish than this might be the film Scarface.

We asked artist Matthew Naimi, who heads up Recycle Here, if he could shed any light on what it might all mean. He was about to head into the Electric Forest Festival, where he would have no cell phone signal, so all we got was a short text reading “tribute to Matty Moroun.” Lo and behold, there’s the Ambassador Bridge in the upper corner — the bridge to Canada Moroun runs with an iron fist. This mural is not a celebration of wealth but rather a critique of greed.

“Detroit Industry” murals

Diego Rivera

Detroit Institute of Arts, 5200 Woodward Ave., Detroit

Oh, the irony. Initially criticized as Marxist propaganda when Mexican muralist Diego Rivera painted them for the Detroit Institute of Arts in the early 1930s, Detroit Industry was designated as a national landmark this year. The murals offer a heroic, idealized look at Ford’s River Rouge Plant (actually tour Ford’s plant today and you’ll find things to be far less dynamic in real life). One of the panels transforms the iconography of a traditional nativity scene into an ode to scientific triumph. A child gets vaccinated, surrounded by three scientists and the animals from which the vaccine was derived. Elsewhere, one of the factory’s machines looms tall and foreboding, like a god. All this earned Rivera the condemnation of the church, which of course only boosted the murals’ popularity. The murals are considered the best of Rivera’s work in the United States (another mural Rivera had done in New York was destroyed by order of Nelson Rockefeller).

During the 1950s, the DIA posted this sign outside the court:

Rivera’s politics and his publicity seeking are detestable. But let’s get the record straight on what he did here. He came from Mexico to Detroit, thought our mass production industries and our technology wonderful and very exciting, painted them as one of the great achievements of the twentieth century. This came after the debunking twenties when our artists and writers found nothing worthwhile in America and worst of all in America was the Middle West.

Rivera saw and painted the significance of Detroit as a world city. If we are proud of this city’s achievements, we should be proud of these paintings and not lose our heads over what Rivera is doing in Mexico today.

The national landmark designation doesn’t change the ownership status of the murals or grant any new protections or rights, leaving its place among the rest of the DIA’s art in possible bankruptcy negotiations in jeopardy. When we spoke to DIA director Graham Beal earlier this year, he was skeptical of what this new federal designation could mean for the museum. “I know from previous experience that these designations can come with real restrictions,” he said. “I wanted to find out what those restrictions were, but I was told, ‘Too bad, you don’t have any standing. Get used to it.’”

American Flag

Askew1

8600 Joseph Campau, Hamtramck

This mural, painted by New Zealand street artist Askew1 as part of the Detroit Beautification Project, takes the familiar colors and shapes of the American flag and abstracts them, creating a psychedelic trip that spans the entire length of this long wall.

“I come from a country with a red, white, and blue flag also — most of us former dominions of England have that, as the flag is based around the use of the Union Jack,” Askew1 explains via email. “I was thinking a lot about the cultural influence of America, and for us [who] grew up on a remote island deep in the South Pacific, U.S. media and entertainment was a beacon of everything we thought was relevant and cool growing up.”

However, the use of the darker red and black suggests the colors of the Yemeni flag. The message is clear — Hamtramck’s Yemeni population is as American as apple pie.

Askew1 tells us via email that the double meaning wasn’t intentional. “I’m very spontaneous with how I work on outdoor paintings and often I seem to draw subconsciously from the vibe, history and people of the area,” he says. “I’m not a spiritual person and, as hippie as it sounds, I feel everyone and everything is connected […] if you’re switched into it on an intuitive level, you can feel the vibration and resonance of life around you.

“That particular corner there were a significant number of Yemeni kids playing football on the vacant lot, hanging around and asking me loads of questions,” he says. “Their families were often in the mosque across the street and while they were, the boys particularly seemed to have a lot of freedom to hang out and get up to all sorts of fun.”

Askew1 thinks his status as a foreigner gives him certain perspective on the United States. “I don’t know if it’s unique, but it is certainly informed by being an outsider with a close group of friends out there, people I consider family,” he says. “I can have a degree of cynicism about the opulence, wasteful and cavalier attitudes — and often very bad foreign policy — but then again, so do my American friends, so I’m not that unique in that sense at all.”

Similar to America being a “beacon of cool” for the rest of the world, Askew1 thinks what’s happening in Detroit could be a warning of things to come, such as the current water issues in the city, for example. “In my personal opinion, these are indicative of battles that will occur worldwide over the next decade or so,” he says.

Native Americans

Sintax

Grand River Avenue and Vermont Street, Detroit

“I’ve got a lot of indigenous people on my father’s side,” says street artist Sintax. “I’m real in tune with indigenous people in Michigan. I paint my ancestors because I think it represents not only Michigan [but] America — they are the forefathers of the land. We should always pay homage to that. A lot of this land is sacred burial ground.”

Sintax’s paintings certainly have a provocative, confrontational quality about them, especially when compared to more cutesy, cartoon character street art. “A lot of street art is cliché to me,” he says. “There’s always a message to what I paint, no matter I do.”

Sintax is highly defensive of his paintings, and takes it as a sign of disrespect when other people paint over them (despite the fact that street art is widely understood to be, by its very nature, a temporary medium). “A crew from California came through and repainted this wall. You get these guys from other cities coming here and painting over our stuff, and making a big production and getting paid for it,” Sintax says of efforts like the Detroit Beautification Project, which attracts artists with international clout to Detroit.

“Why can’t local artists meet up with these out-of-town guys and work on a mural together? When you push people to the side, you’ve really made a statement,” he says.

Recently, Sintax was accused of pulling a gun on artists he found painting over his walls. “I have a permit to carry my protection,” he says. “I’m never going to be put into a situation unless I’m threatened. And that’s all I’m going to say on that.”

Captain America

fel3000ft

St. Andrew’s Hall, 431 E. Congress St., Detroit

Speaking of Sintax, he also organized this friendly graffiti battle in an alley next to St. Andrew’s Hall between his Detroit crew and a graffiti crew from Chicago. Sintax’s crew painted the characters from The Avengers on one side, while the Chicago crew painted the villains on the other wall. “I did the Incredible Hulk,” Sintax says. “Everyone picked their alter egos.” Captain America was painted by the street artist fel3000ft, who Sintax regards as an elder in Detroit’s graffiti scene. “I’ve been working under him since I was 16,” he says. “He’s one of Detroit’s original graffiti writers, and Captain America is one of the first Avengers. He’s like the oldest one. [fel3000ft] represents that Captain American attitude: ‘We can all do this as a team.’”

Fat Captain America

Sever

Grand River & Calumet Street, Detroit

Another take on the character Captain America as a representation of the United States offers a more critical view of America. L.A.-based artist Sever painted this obese Captain America, whose shield has been replaced with a corn dog in one hand and a Big Gulp in the other. “It’s a political message, funnily enough, directed at those same people who might not understand it, who just sit back and drink their Slushy and complain about the Mexicans moving in,” says Detroit Beautification Project organizer Matt Eaton. It looks like someone wrote something on his stomach, but whatever it was, was painted over in blue.

“United We Stand”

Artists unknown

Joseph Campau and Denton, Hamtramck

A simple, blocky American flag is painted with the words “United We Stand” scrawled beside it; tiny handprints around the flag suggest that children painted it. Locals say it went up shortly after Sept. 11, 2001. This painting has an innocent, naive quality that’s both cute and admirable.

“America United September 11, 2001”

Jeff Von Buskirk

Marquis Theatre, Northville, 135 E. Main St., Northville

This massive, photorealistic painting of the American flag was painted by local artist Jeff Von Buskirk and commissioned by Marquis Theatre owner Inge Zayti in the aftermath of the Sept. 11 attacks. The mural went up in summer 2002; ever since, it’s been one of downtown Northville’s most visible landmarks. There’s no political commentary here — just a stoic, straightforward memorial to one of the defining moments of a generation in American history.

Buskirk says great care was taken in creating the design. “There was this interesting chimney on the back, so there was this idea to get the flag to wrap around the chimney, and have depth to it,” he says. Buskirk also wanted something that would fit with Northville’s Victorian sensibilities.

After 10 years, the substrate it was painted on began to peel, and now the mural is slated to be updated this month after ongoing efforts by the community to raise the $19,000 necessary to refurbish it. Buskirk will once again paint it, and work is expected to take a month to complete.

Zayti died last year, but her mural lives on. “My wife has mentioned to me that she’s seen Vietnam veterans on Harleys pull up with a priest, also [on] a Harley, and they do a little service there in front of the mural,” Buskirk says. “It’s taken on a life of its own.”

Buskirk also remembers how three years after he originally painted it, the city wanted to build a parking garage in the lot behind the theater, which would render the mural invisible. “[Zayti] was this older German woman. She was really interesting — she’s such an important part of that flag,” Buskirk says. “We went to a council meeting with her. They were talking about the parking garage and she stood up, with her little tiny body, and said, ‘You will put this garage up over my dead body!’

“I think she really understood having freedom, and having free speech,” Buskirk says. “Every day she would park her car in front of her theater, and every day the police would keep ticketing her. She kept parking there, because she felt like it was her property. It’s interesting because now that she’s passed, you have all these people in Northville coming together to restore her flag. It’s like she’s exercising her free speech beyond her death.”

Check out a slideshow of a behind the scenes look at the creation of the cover art for this story here.