Mutate, don’t stagnate: Mark Mothersbaugh in conversation

[

{

"name": "GPT - Leaderboard - Inline - Content",

"component": "35519556",

"insertPoint": "5th",

"startingPoint": "3",

"requiredCountToDisplay": "3",

"maxInsertions": 100

}

]

Mark Mothersbaugh is a composer, musician, and visual artist from Akron, Ohio. He is best known as the co-founder and leader of Devo, a band formed around the concept of de-evolution: the idea that our species has stopped evolving and started going back the other way.

His body of work has recently been collected in a traveling exhibition featuring drawings, paintings, videos, postcards, musical instruments, rugs, and other materials. The retrospective and its accompanying book are titled Myopia, referring to the fact that Mothersbaugh is legally blind.

This Thursday, Sept. 29, Mothersbaugh will visit University of Michigan as part of its Penny W. Stamps lecture series, where he will be in conversation with Myopia’s curator Adam Lerner.

The event takes place in the Michigan Theater — also home to the Ann Arbor Film Festival, which in many ways helped launch Devo’s career. As art students at Kent State, the band made a film called In The Beginning Was The End: The Truth About De-Evolution, which won first prize at the Ann Arbor Film Festival in 1977.

Metro Times: What do you remember about the Ann Arbor Film Festival?

Mark Mothersbaugh: I didn’t go to it. That would’ve cost money, like fifty bucks or something, and then I would’ve had to find a place to stay, and I didn’t have any money at all. Nobody went because we weren’t really expecting anything. So we just [entered the film], cause what do you do with a film that has songs in it back in those days? There was no MTV back in those days, and no television that would be interested in an unsigned band’s seven and a half minute film. There was no such thing as a record company in Ohio as far as we knew.

MT: When you made that film, was it conceived as a promotional video for Devo, or more of an art film? What was the idea behind it?

Mothersbaugh: We didn’t think of ourselves as a rock band, we thought we were an art movement. We were art students and we were doing visual art before we were doing musical art together. And then Chuck Statler, who had gone to school with Jerry [Casale] and I, suggested we get together and make this film. So Jerry and I wrote the film and created it, and we thought it was just all part of being art De-vo.

MT: What were the effects of winning that award?

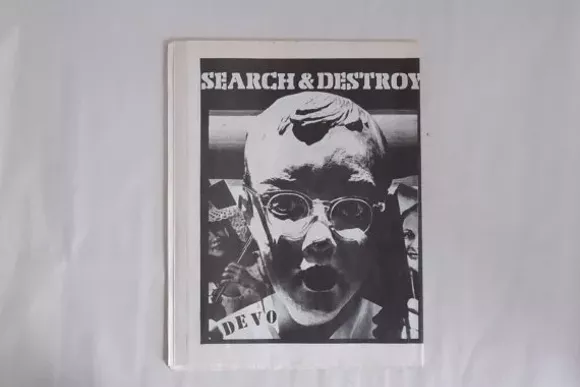

Mothersbaugh: It had a profound effect on our career. We were in Ohio, and we would on every other weekend or so, get in a van together, put our equipment in it, and go to New York City and play CBGB’s and Max’s Kansas City, and come back to Ohio. In Ohio, no one was really interested in hearing original music. They wanted to hear bands in a club playing cover tunes. After the film [won an award at the AAFF] someone put it on a collection of film shorts that were touring the country. When that collection of shorts got to the west coast, we were then on the radar of the local music scenes - the punk music scenes which were kind of new at the time. The art music and punk music were kind of blurred and mixed together, so we kind of fit in. Slash magazine, which was a punk 'zine that was documenting what was going on in LA in the mid 70s, late 70s, and the [SF-based] magazine Search and Destroy, which was an excellent publication that still holds up to time as interesting reading. Both became fans and they reprinted photos that they took off the screen of the film in both their magazines, and so the local punk scenes knew who we were.

But at the same time the commercial music scene [also saw the film]. An A&R guy from A&M records, who came to a screening of these short films, when he saw the Devo film he was like, ‘Wait I just signed the Tubes. These guys look like they’re a lot like the Tubes!’ So this guy gave us enough money, which was $2000, so that we could afford gas and we could drive from Ohio to Hollywood, and he put us in some apartments for one month while we were here.

And he had arranged for a showcase. We were opening up for a band that had just gotten a record deal called the Clowns, and they played Van Halen music before Van Halen. And nobody saw them, but as their opening act, all these kids that had been reading Search & Destroy and Slash, the local scene, showed up and filled the place up for Devo. The guy from the record company was kind of shocked and confused cause all these kids were there to see Devo and he didn’t even know how they knew we were gonna be there. People like Iggy Pop showed up that night. The next day though, he called us into his office and he said, ‘That was so weird last night. The Clowns didn’t have anybody there to see them, but you guys had a full house. I don’t know how these people know about you and found out about you but it must have been how I did. But I’ve gotta tell you, I listened to your music and I went home and I tried to remember some of the songs so I could play em on the piano, and I just couldn’t remember any of your melodies. They weren’t memorable. Your stuff just wasn’t something that was catchy.’

So we didn’t get signed by him, but we refused to go back to Akron. After we got thrown out of the apartment that he had rented for one month for us, we kind of lived by our wits. People would come to a Devo show and say, ‘What are you guys doing after the show?’ And we’d go, ‘We don’t have anywhere to go.’ They’d go, ‘You can stay at my place.’

We existed like that for quite a while, but the film was really our entrée into the world of both the world of street music and art, but also it had this other side where it was our introduction into the world of pop music and this eviler side. People would come see us in New York and they’d go, ‘Ok, you gotta go see this band, it’s the weirdest band. They put a sheet in front of the stage and they play films of them performing songs, and then they take down the sheet, and then they perform the songs!’ People heard “Secret Agent Man” and “Jocko Homo” twice – first on the film and then we played it live.

So the film really had a lot to do with us getting people interested in what Devo was doing. We got introduced to both the high art world, everybody from Salvador Dali and Andy Warhol and those kind of people, to the low world, which was Warner Brothers, Virgin Records - that whole scene also became interested in it.

MT: After you were kicked out of the apartment in LA and were just crashing wherever, what happened?

Mothersbaugh: We just looked for places to live. I had nowhere to go, and Iggy Pop said, ‘Well you can come sleep in my living room.’ So I moved to Malibu with Iggy Pop. I lived in his living room and Devo rehearsed there. He would be up all day making painting of himself naked, larger than life size paintings, and Devo would come over and rehearse during the day at the same time.

So things like that happened, and then eventually we went back to New York and played, and Brian Eno and David Bowie came to see us, and Brian Eno said ‘I wanna produce you guys,’ and we said, ‘We don’t have a record deal,’ and he said, ‘Don’t worry about it, I’ll pay for the record. In fact, let’s go to Germany. There’s a studio I like in a city called Cologne where all the electronic bands from Germany like to record.’ I think he had done his Music For Airports there just a couple months before that. Brian flew us over to Germany and we recorded an album, and David Bowie was with us the whole time.

Then the film comes back because at the end of that, right before we left Germany, I got a phone call that was from Kraftwerk. And they said ‘We’re about to do our tour, and we want your film to be our opening act.’ So The Truth About De-Evolution was the opening act for Kraftwerk on their tour.

They just loved the film, and like I said, there was no such thing as music video at the time. So somebody making films out of their songs was a big deal. Now, my kids have done that. They’re 12 and 14. The world changes really fast, it’s so much more democratized now. It’s not like it used to be, where it took us like a year to make our first film, and it’s only seven and half minutes long. It’s kind of sad, but we had no funds. Now, if you can get access to an iPad, you can write the music right there, record it, and if you like what you did, you can make a film to go with it, all in one weekend if you want to. I love that, I love the way the world is. I think it’s such an amazing time to be a kid, I would love to be a kid right now.

MT: What do you tell your kids about de-evolution?

Mothersbaugh: Use it or lose it. Choose your mutations carefully, that’s the important thing with de-evolution. Rather than let other people choose them for you, you choose the ones that are best suited to you.

MT: What did your parents thing of your work?

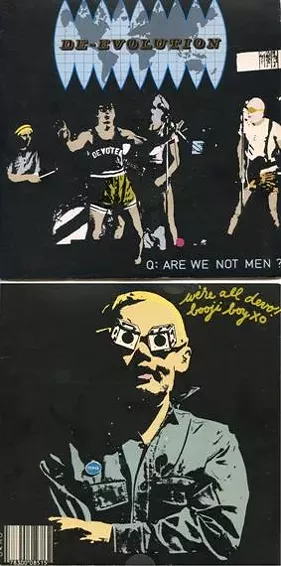

Mothersbaugh: They both passed away, but my father was in not only the first film we made but at least half if not more of all of the films that we made. He was Booji Boy’s father — he was General Boy. He loved it, he really liked Devo and he wanted to go on tour with us as General Boy. When you’re a kid the last thing you want is your dad to come along with you on tour. I’m thinking, that would be the last thing I want. So we didn’t take him. But in retrospect I think, Wow, what if we would’ve? That would have been kind of cool.

My mom was just always worried whether we were getting enough to eat or not. She’d go, ‘Are you boys eating?’ We’d go, ‘Yeah mom, we’re ok.’ ‘Ok, I’m praying for you.’ ‘Thanks, it’s working.’

MT: In the Myopia catalog, you mentioned that there were some Booji Boy activities outside of Devo performances. What else was he up to?

Mothersbaugh: Well, the characters Booji Boy, China Man, Clown, and Jungle Jim, all started off as rubber masks from novelty shops in Ohio. We entertained ourselves in those days, back in the early 70s. I’d be Booji Boy all day — we’d just be these characters all day sometimes. I loved having an alter ego, because I found out that when you wear a mask, you can take on a whole other persona. It made me change the way I feel about myself in some ways, as a secondary effect.

Booji Boy ended up becoming the infantile spirit of de-evolution. Where Devo shows and Devo songs were really worked out ahead of time — we would really work hard to make them sound exactly right — Booji Boy was always the agent of chaos. He still comes out onstage in the final song, and he’ll do a rap or he’ll do music, he’ll tell a story in the middle of “Beautiful World” or “Words Get Stuck in my throat” or whatever we use as the final song. Nobody knows what he’s gonna start talking about til he starts talking, cause it’s stream of consciousness. He might one night talk about Michael Jackson getting out of his grave and marching over there to proclaim it’s a beautiful world. Whatever story he tells, we never know exactly what he’s gonna say, so it’s always kinda surprising, even for me, what comes out of his mouth. That’s kind of like the unpredictable part of Devo.

MT: Does Booji Boy still have any non-Devo performances these days?

Mothersbaugh: Very rare. There’s other people that have taken up the banner. I’ve never participated in one, but I’ve heard of marches on Main Street in Akron Ohio where there’s 30 or 50 Booji Boys all misbehaving together. The original Booji Boy totally approves of all of that. He likes to be reinterpreted, and he thinks that Devo sometimes was stronger in the reinterpretation — much in the same way that Mick Jagger, when he heard our version of “Satisfaction”, he told Jerry and me ‘That’s the best version of that song I’ve ever heard.’ Booji Boy approves of positive mutation.

MT: What was the songwriting process like in the early days of Devo?

Mothersbaugh: The songwriters were primarily myself, Jerry, and Bob Mothersbaugh, but we made a conscious decision to split the publishing side of the royalties equally between all five of us, so that would just help encourage the non-writers to participate and help make the songs better. We didn’t want it to be like a lop-sided thing where people were fighting over what songs to put on the record. We wanted it to be, whatever were the best songs, those were the ones that made it on the record.

We were two sets of brothers, basically. At one time it was my two brothers, and Jerry and I that were the only ones in the band. Then my brother Jim became obsessed with circuit bending and electronics and sound in general, and he stopped being a performer in the band and just became like our main audio scientist. Then Bob Casale came in, so it was two sets of brothers. And my brothers, we used to sleep in the same bed when we were in grade school, so we had to put up with each other from an early age. So it was pretty much always a collaborative work process.

And then why I think the early songs were stronger in a lot of ways than a lot of the later songs, that sometimes even had, you know, more interesting lyrics, I think [was] the technology. [Early on] we had a four track Teac tape recorder. So we would write four tracks, mix them down to two tracks, then we’d have two open tracks, so we’d have six tracks total that we could mix our music onto. So it meant everyone pretty much had one track for their instrument. You had to play something essential or not play at all. I think that made us think about the music in a really interesting way that involved reductive synthesis. What happened after that is, people got access to 24 tracks, and 48 tracks, and now [with] digital recordings they can have hundreds of tracks on a song. I think that was Devo’s downfall, that technology. While some of it went in a really good way for us, some of it went wrong, and I think multi-tracking made us make musical tracks that were less interesting.

MT: I read an interview with you where you said that all the music you compose for Devo and films and commercials and stuff has the same essential DNA.

Mothersbaugh: Yeah. I think it’s not uncommon for an angry young artist to make a statement, and basically do permutations on a theme afterwards. I just introduced [a film screening at] the Bruce Conner show at [the Museum of Modern Art] last weekend. [Conner made a film for the Devo song “Mongoloid”; it's embedded right above here.] I went upstairs and walked through the show, and you could see it. There was a thread that went from one end of his career to the other end. It wasn’t like there was a disconnect when he went into film; his films reflected a lot of his sensibility from his earlier paintings and cast shadows on what was to follow later. I don’t think that’s an uncommon element. There are artists that totally reinvent themselves, and some of them just say they do. David Bowie, even though he said he was reinventing himself every time, when you step back and take a look at who David Bowie was, I think it all fits into a logical trajectory.

MT: So if you had to sum up what the DNA of your work is, what would you say?

Mothersbaugh: Mutate, don’t stagnate.

MT: What do you remember about filming Human Highway?

Mothersbaugh: Well, Toni Basil’s the one who told Iggy Pop we were playing in LA. Her boyfriend at the time was Dean Stockwell, who made movies. And they were working on Human Highway, and they told Neil about Devo, and Neil became fascinated and he wanted us in his film. So we said, ‘We’ll be in your film, but we wanna trade off. We want some footage for a song called “Shrivel Up.”’ And he said ok. So they were gonna shoot two songs and let us keep the footage for one of em. And we said, ‘You have the buy us some cowboy hats and cowboy boots,’ and he said ok.

And then we got there, and it was the craziest thing, it wasn’t like a real film! It was like a big home movie. These guys would get ideas and then they’d call everybody up and they’d head out somewhere to shoot something. But they had a rough idea for the film. [Neil] would’ve said fantasy, but the way it came out in the film, it looks like Devo is Neil Young’s nightmare.

We kind of pissed them off at the time. We were disruptive, and we referred to Neil Young as ‘Grandaddy Granola.’ But when I went back and saw the film, in the 90s in an art house, I was kind of impressed with it. I thought, ‘That’s a really good film.’ And I loved the footage where Neil’s jamming with Devo in a studio in San Francisco, and Booji Boy’s playing a synthesizer and singing “Hey Hey, My My,” and Neil starts crushing my playpen with the guitar, I love that. When I saw it in the film I went, ‘That’s pretty wild. Look at Neil Young; he’s doing something kinda crazy.’

We were kinda anti-hippie at the time, and I think it was like we were like not exactly what [Neil] was expecting. It’s funny because now I love it much more than I did.

MT: How did you originally become fascinated with potatoes?

Mothersbaugh: Well, I hated school. Public school was the worst thing that was ever invented. Cause I was the little kid with big glasses, I was the smallest guy in my class. Everybody else liked hillbilly music and I liked the Beatles, so they were allowed to kick the shit out of me whenever they wanted to. I was tortured for like twelve years, that’s just the way it was.

I kind of went to college by accident. I’m watching the news, and I’m watching all these Vietnamese people get killed, by Americans, and I said ‘I don’t wanna do that. I have absolutely no interest in killing any Vietnamese people.’ By some miracle, a teacher in Akron had filled out the form for me to get a partial scholarship, and that was enough to make me say, ‘Hey, I could try that.’ So I decided I would try going to school.

When I went to college, instead of being in a class of a hundred people, that were looking for the nerd today that they could beat up again just so they could prove that they were on top of the Darwinian heap, I was all of the sudden anonymous in a school of ten thousand people. I loved that. I found out in my freshman year that kids would be looking at their watches and as soon as it hit 3:30, they would bolt for their dorms and their sorority houses and wherever else people stayed and start partying for the evening. I had the whole art department to myself. I didn’t have to queue up in line with other students. That meant that in one night, I could just burn a screen, print a color, put it on racks to dry, burn a screen, print another color, put it on racks to dry. I could finish a piece of art in one night instead of in a month.

I was making all these small pieces that were like graffiti – I didn’t know what graffiti was at the time, but I was just putting up artwork all over the campus. So Jerry came – he was a grad student at the time and I was a sophomore. He showed up and said ‘Hey are you the guy putting up pictures of astronauts holding potatoes all over campus?’ And I’m like, ‘Yeah,’ and he goes, ‘What’s a potato mean to you?’ And we start talking about how the potato kind of represented the proletariat of the vegetable kingdom. Potatoes were dirty and asymmetric and they lived underground, but they had eyes everywhere, all over em, so they could see everything. And they were also the unglamorous food that was a staple of everybody’s diet. Nobody ever talked about potatoes, but they were on everybody’s dinner plate every day, whether they were mashed, or scalloped, or fried. So we kind of identified with potatoes, and we accepted our badge of proletariat standing and embraced our spud-ism.

The lecture occurs from 5:10 to 6:30 p.m. on Thursday September 29 at the Michigan Theater (603 E Liberty St in Ann Arbor). For those unable to attend, the event will be live broadcast on WCBN FM Ann Arbor – 88.3 FM in the Ann Arbor area or available to stream from anywhere in the world at http://wcbn.org.