I’d always thought there’d be a chance to hear Mal Waldron and ask about the two of him and the space in between.

He’d come to town — eventually, though no one had booked him here since the early ’80s — and there’d be, as we say in the newspaper business, a “peg” and a reason for a long interview. Or I’d be on a trip and pick up a local paper to find in the small print: “Pianist Mal Waldron appears tonight at … ” And I’d rush there, saunter into the backstage throng after the set and squeeze in a question or two.

The career of the first Mal alone encompasses much of the 1950s and early ’60s jazz scene. Born in New York, he was inclined to a career in the European classical tradition but wound up in the company of hard-stomping players like Big Nick Nicholas and Ike Quebec. He played with Charles Mingus’ Jazz Workshop, including the recording session for “Pithecanthropus Erectus,” the extended tone poem where Mingus summed up the rise and fall of the human race.

Waldron was Billie Holiday’s accompanist for the last two years of her life and co-wrote “Left Alone” with her. Frank O’Hara froze both of them in time in his poem “The Day Lady Died,” which records the small events of a 1959 New York afternoon (shoeshine, trip to the bank, gift shopping) interrupted by the sight of Billie Holiday’s picture on a newspaper’s front page:

and I am sweating a lot by now and thinking of

leaning on the john door in the 5 SPOT

while she whispered a song along the keyboard

to Mal Waldron and everyone and I stopped breathing.

Waldron played on Max Roach’s salute to the sit-in movement, The Freedom Now Suite; he co-authored the song “Straight Ahead” with Abbey Lincoln, and in the words of his former student Ran Blake, mastered shades of anger when he performed with her: volcanic, suppressed and “cool and calculated.” Blake put “Straight Ahead” on his short list of “the most harmonically sophisticated ballads ever written.”

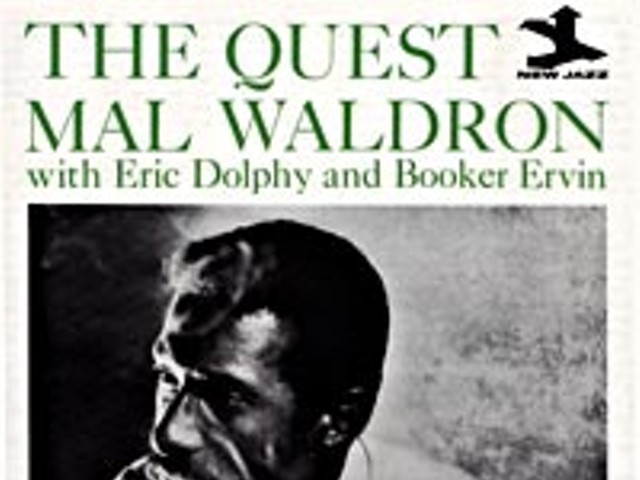

Waldron recorded with the likes of Oliver Nelson, Eddie “Lockjaw” Davis, Eric Dolphy and John Coltrane. He penned dozens of beautiful tunes, including the jazz standards “Soul Eyes” and “Fire Waltz”; he turned out three film scores and wrote music for the productions of LeRoi Jones’ The Slave and Dutchman.

And in 1963 he cracked — variously attributed to overwork or drugs. No longer able to play, he had to listen to his old records to re-create himself. He relocated to Europe. And his later records tend to a freer, sparser, often more ruminative, heavier style.

Lots of artists were moving further and further away from the old song forms in the mid-’60s, often turning to repetitive, mantra-like figures. (John Coltrane’s “My Favorite Things” was the movement’s first and biggest hit.) But Waldron’s figures were his own as was his manner of wringing and ringing all he could from them. Satie and Monk were among the composers he cited as influences, and if you listened you could hear them clearly, particularly in those second career phrases. In one interview, he tied his “economic approach” back to his childhood: “We were never rich people and never threw anything away. So, when I have a note, I make use of it and milk it in every possible way.”

Among his many sessions in Europe, he recorded the first disc on Manfred Eicher’s upstart ECM label. He reunited with old friends from the states, including Jeanne Lee, Jackie McLean, Marion Brown, Jim Pepper, Max Roach and, most often, the soprano saxophonist Steve Lacy. (Where others danced across Waldron’s musical architecture, Lacy seemed to meticulously explore the insides, room by room.)

None of Waldron’s later compositions has caught on the way “Soul Eyes” and “Fire Waltz” did decades earlier, though “Snake Out,” a wild, bumpy sleigh ride of a melody he often rode with Lacy should. At the very least, a number of his later works deserved to be better known.

I’ve often marveled at “The Seagulls of Kristiansund,” from his 1989 Soul Note recording of the same name. He said it was inspired by the morning ballet of birds on a Norwegian beach. It’s somewhere between a ballad and a dirge, with an aching, wistful beauty on which the musicians elaborate for nearly half an hour. In recent years I’ve been struck, too, by the personnel: trumpeter Woody Shaw, saxophonist Charlie Rouse, drummer Ed Blackwell … all original, all deceased.

A little more than a week ago an e-mail from a Waldron associate in Brussels bounced and zapped among jazz fans and listservs around the world, carrying the word that Waldron that evening had “slipped away, quietly and without pain, after a very brief illness.” He was 77.

Scanning the credits on Seagulls the next day, I sadly realized that only the bassist, Reggie Workman, now survives.

Check out George Tysh's review of Mal Waldron's The Quest. W. Kim Heron is the Metro Times managing editor. Send comments to [email protected].