The Oakland Avenue Farmers' Market in Detroit's North End is one of those small-but-mighty neighborhood markets that accomplishes a lot with a little.

Each Saturday, it offers fresh fruit, vegetables, and other healthy foods in a historically low-income and black neighborhood where such options aren't readily available.

Just as important is its contribution to the neighborhood's economy. Most of the profits generated since it launched in 2009 fund the adjacent Oakland Avenue Farm. That operation provides 13 full- and part-time time jobs that pay a living wage — also rare in the North End — in addition to teaching residents to grow and cook their own food. So supporting the Oakland Market is a small contribution to the neighborhood's economy.

However it has competition from another farm, and the Oakland Market can't beat its prices. That's because the other farm — Michigan Urban Farming Initiative — is giving away free produce every Saturday. It's run by Tyson Gersh, and, for obvious reasons, his decision to hand out produce when the Oakland Market sells food creates tension.

But it's not an isolated situation. Oakland Farm executive director Jerry Hebron and other leaders in the urban farming community say MUFI's approach and practices — intentionally or not — are undermining the city's entire urban farming movement.

Gersh brings in a lot of corporate volunteers and others from around southeast Michigan to work on several acres of city-owned land, and he receives donations from companies like GM, BASF, MiracleGro, and Stanley Black&Decker. So he's in a position to give away free food.

MUFI is also different from the Oakland Farm and Detroit's other urban farms in that its mission doesn't appear to be about food security as much as development. Instead of just a farm, Gersh is attempting to engineer an "agrihood."

Simply put, an agrihood is a fashionable urban planning concept in which a community is designed and built around a functioning urban farm that Gersh says "drives up real estate values." They exist to some degree in Detroit on Farnsworth Street or Banglatown, minus the focus on real estate value. Elsewhere in the nation, people usually build agrihoods in rural settings. Gersh's development is billed as the first sustainable agrihood and is the first in the city with an active public relations component, so he gets a lot of positive media attention from local, national, and worldwide outlets.

"I want to be Elon Musk when I grow up," Gersh says with a laugh when we discuss MUFI's branding during an interview at the North End house he rents.

But his approach and ideas are raising questions about the purpose of urban agriculture in Detroit. Should it aim to improve food security, strengthen local economies, provide jobs, and empower longtime residents? Or is it about giving away free food?

The latter charitable model may be well-intentioned, but it only addresses the symptoms, not the root causes of poverty, says Shane Bernardo, a former farmer who now works as an independent food justice and racial equity consultant.

"Neocolonial projects like MUFI demonstrate that well-intent is not enough to address the systemic issues around food security and poverty. Food security and poverty have less to do with access and more to do with structural and historical disparities around power," he says. "That's what sets charity programs like MUFI apart from more grassroots, self-determined models like Oakland Avenue, D-Town Farms, and Feedom Freedom. As long as we only address the symptoms of food security and poverty, we also perpetuate the disparities of power that create them."

It's also leading to discussion about whether urban farms should be a development tool that's wielded in struggling neighborhoods. If Gersh is successful, will other developers replicate the model and ultimately cheapen an important grassroots industry? Is Gersh — as one gardener put it — "gentrifying the urban farming movement" while getting and taking an outsize portion of credit for it?

Beyond the farms, multiple sources say they're concerned about Gersh's attempt to lead the North End — in which he arrived around six years ago — and perceived disrespect for black-led organizations and longtime residents.

Those issues sometimes play out in the North End's block clubs and association meetings, of which Gersh is a part. Pam Martin Turner, executive director of the Vanguard Community Development Corporation, alleges that Gersh is trying to derail a mixed affordable and market-rate housing project that the CDC is developing, and regularly disrupts its other neighborhood improvement efforts. (Gersh acknowledges that he strongly opposes the project.)

Turner, Hebron, and other sources we spoke with characterize him as disrespectful to and confrontational with those who don't support his agenda. Emails provided to Metro Times support that, and a Vanguard employee filed for a personal protection order. The order wasn't granted after the first filing, and was withdrawn after the second, but several women tell Metro Times that they now have men present when meeting with Gersh. Gersh says the filings are "completely ridiculous" and claims he has never put anyone in danger.

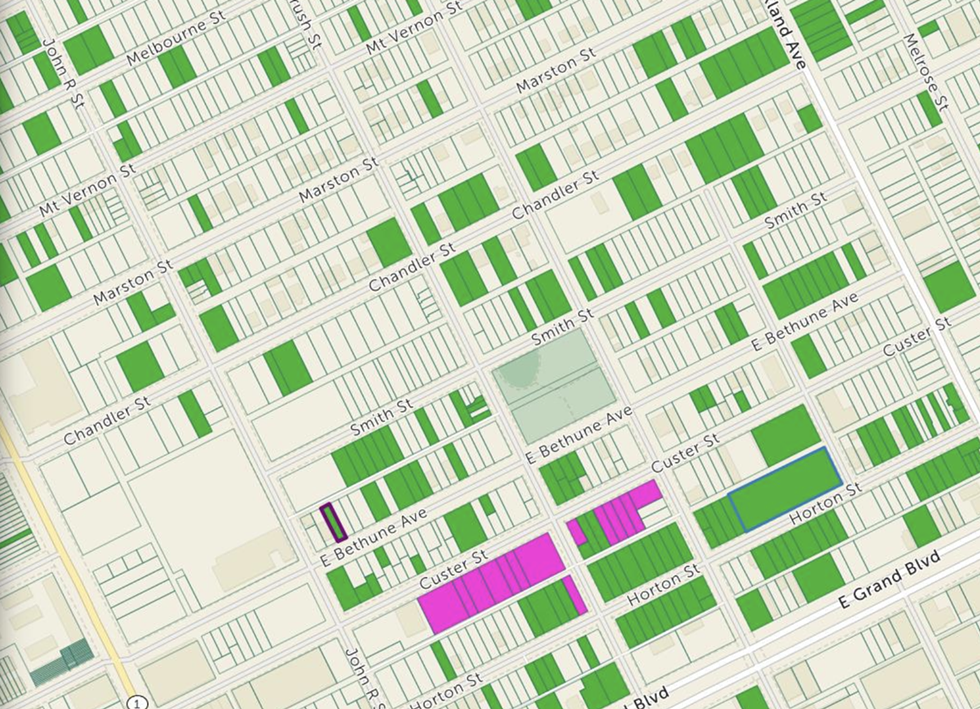

And there's a larger issue: Gersh may have plans for an agrihood, but North End residents we spoke with say there are mixed levels of support. When asked about support, Gersh pointed to a thick stack of petitions filled with signatures of those who back the project. He also pulled out one of the many North End parcel maps he created. This one was color-coded to show which neighbors had the opportunity to support him and which didn't.

However, one resident we spoke with said they signed the petition to avoid confrontation. Others say the farm is an asset, but don't approve of Gersh's approach, or that he is trying to take over city-owned land.

"Tyson puts himself out there as the gatekeeper" of the North End, Hebron says. But there's concern about the coronation of a 28-year-old white man from Ann Arbor who is trying to execute a neighborhood-changing plan in a roughly 90-percent black neighborhood. Several sources likened it to "colonialism."

"I'm not in favor of putting a wall around the North End and not letting any white people in, but people need to come here in a way that shows a humility and respect for those who live here already," a North End property owner tells us.

In that way, this is much more than a hyper-local fight. The themes at play are deeper and the same as those found across Detroit that are rooted in power, gentrification, class, race, and economic stratification. It's a story of new Detroit meeting old Detroit.

Gersh's Farm

Still, there's plenty of strong support for MUFI inside and outside of the North End. That includes people of different backgrounds, races, and socioeconomic statuses, as well as many longtime residents. Gersh worked closely with Dolores Bennett, "the godmother of the North End," before she passed earlier this year, and still works with her daughter.

The neighborhood is a historic area that many consider the city's next "it" neighborhood, much like Corktown and Woodbridge have been in recent years. Notably, it's composed of more vacant than active land, which is mostly the result of decades of depopulation and demolitions. The remaining housing stock holds the kind of beautiful, old homes that developers purchase for relatively little and rehab. Its conditions are perfect for full-on gentrification, and many of the North End's residents are working to mitigate those issues.

Gersh's farm sits near the intersection of Woodward Avenue and Grand Boulevard on what's considered some of the neighborhood's best real estate. Sweeping drone shots that accompany articles on MUFI show an orderly farm carved out of an area exhibiting signs of decades of economic distress. MUFI's "agricultural campus" holds a two-acre farm and 200-tree fruit orchard. The nonprofit is renovating a vacant home for student intern housing, building a two-bedroom shipping container home, and building a healthy food cafe.

Since 2011, MUFI – which appears to be run nearly solely by Gersh – distributed around 70,000 pounds of produce to over 2,500 local households within two-square miles of the farm, by the organization's estimation. Around 10,000 corporate volunteers have helped grow and harvest 300 varieties of fruits and vegetables, and the plan is to continue turning the area into an agrihood.

But that's complicated because MUFI doesn't own around 2.5-acres of land on which the farm grew — the city does. It also acquired around 1.5 acres of land that it does own through private sales or foreclosure auctions. Gersh started turning the once-vacant city-owned land into a farm starting around 2011 without official permission, so some call what he is doing "squatting," while others say he is a "steward."

The city appears to want denser development on the land since it's two blocks from Woodward and the QLine streetcar. It's also asking Gersh to agree to sale terms that he says he finds unreasonable before it will sell land to MUFI. Until the sale happens, Gersh can't move forward. The situation led a string of Facebook posts on Dec. 2 in which he publicly criticized the Detroit Land Bank Authority and city, with comments like, "The way the government in this city sabotages its citizens.... reason 104828105728 why I am really starting to hate the City of Detroit."

The farm's location and the public disputes are the sort of things farmers cite when discussing how MUFI damages the urban agriculture movement. We talked to over 10 of its leaders who expressed a litany of concerns, starting with the spot on which Gersh built MUFI. (It's worth noting that many residents and farmers declined to speak on the record to avoid a confrontation with Gersh.)

Urban farms' locations are typically carefully planned and designed to complement adjacent land uses. There's consideration for how one might impact the surrounding city, and there's a real effort to avoid the kind of battles Gersh fights with city hall and some North End residents.

That's because it reflects poorly on all of Detroit's urban farms. As Ashley Atkinson, co-director of the nonprofit urban farm Keep Growing Detroit put it: "The investment that farmers and gardeners have in the land that they tend is often significant, however no one should be exempt from feedback from community institutions and residents. There needs to be a willingness to compromise when it comes to city planning efforts. If everyone operated like Tyson, then our community would be wiped out — no one would want to work with us."

The face of urban farming

There's a general feeling among those we spoke with that Gersh presents himself — or is presented — as the face of urban agriculture in Detroit, as is evidenced by all of the positive press. If the face of a movement is regularly angering or feuding with the city, organizations, and individuals in the community, then there are consequences for other farms.

"When he presents himself as representing all of Detroit's urban ag movement, people get a bad impression of us, and it ends up being detrimental to all of us," one farmer tells us.

Alice Bagley — who runs a garden on Clairmount just across Woodward from the North End — says the narrative MUFI is pushing, that it's "the first or biggest and best," runs counter to how the urban agriculture community ideally functions.

Farms regularly work together toward a common goal. For example, Hebron says her farm and others aim to grow two percent of the produce that's consumed in the city.

"Part of the value of urban agriculture is the collaboration and sense of community ... and that important collaboration does not fit his narrative of 'We're the first and only,'" Bagley says. She adds that it should be presented as "an important, long-term part of the city that needs to be preserved, that benefits everyone in the long run. That is more honest."

That also becomes an issue of respect for those who have been at it for decades.

"People have been here farming and working through the struggle when it wasn't even legal, when we were underground trying to do it," Hebron says. "How dare you not even give homage to the fact that many of us have been doing real work for much longer."

Post-colonialism

During the warmer months, bus loads of people from corporations and suburbs arrive in the North End to do their good deeds at MUFI. They work the farm instead of neighborhood residents who need employment and work experience.

MUFI's model of relying on corporate volunteerism over employment eliminates an important benefit of urban farming, and is one of the central issues with the farm, Hebron says.

"White people go to MUFI and do their mission work and they leave and feel good, and the impact is good. But my thing is, 'Where's the community support? If this is a community space, what did the community put into that?'" she asks. And even people who can afford to pay for produce are grabbing it for free at MUFI on Saturdays.

"The free food is a mechanism that MUFI uses to gain community support, but at the same time ... when you give needy people food on a continuous basis they become dependent," Hebron adds. "We don't believe in that strategy."

Beyond that, there are concerns with Gersh's partnerships with companies like MiracleGro or chemical company BASF. While Gersh notes that the latter develops green technologies, others label it a multinational corporation with a poor environmental record.

But Gersh dismisses the idea that his model impacts others. Those who think it does are "on another planet," he says, and urban farms boosting the local economy "is not a thing." He says he doesn't believe Detroit farms are money makers or job creators, and pulled up documents with his detailed MUFI pro forma that he says supports his position.

The revenue on three acres of produce is relatively low, Gersh says: "When you talk about what kind of revenue an apartment complex can generate [on three acres] — overnight it's more."

"Our stance has really evolved to be that urban ag in and of itself is not this jobs creator," he adds. "But we do believe in addressing structural inequality in the food system through simply the increased access to produce. You talk about people who are parading around creating jobs, well you have two part-time employees and you're occupying how many acres? This isn't a sustainable, long-term revenue model. ... This is transitional land use at best."

"This isn't a slight," he adds.

Hebron concedes it's tough to make money, but says that's why farms must develop multiple revenue sources. She points out that her 5.5-acre farm provides 13 full- and part-time jobs, and it's a place where those with employment barriers go to learn skills and build a resume before moving on to bigger things.

Gersh's North End

Ette Garth's family has called Horton Street home for two generations. She graduated from high school when she was 16 years old and started at Wayne State University, so her dad gave her the house at 250 Horton in which she still lives. She's now an administrator in Detroit Public Schools, owns nearly every parcel on her block, and speaks about her street with pride.

So she was caught by surprise a few years ago when Gersh — whom she hadn't yet met — and two women knocked on her door early one Saturday morning to ask if Garth wanted to sell her house.

"I proceeded to walk outside on my front porch because I thought this might be some kind of a practical joke," Garth tells us. "I walked outside and looked around because I thought one of my girlfriends put a 'for sale' sign out there as a joke. I realized they didn't, so I looked at him and I said, 'Wait a minute. There isn't a sign? Joke's over. Why would you want think that I want to sell my house?'"

The incident left Garth shocked and angry. Imagine if a black woman moved to a largely white city and tried the same thing, she says.

"It's his white entitlement that's throwing me for a loop. I don't understand it because nowhere in the world can an African-American set up shop like this, take over land, and it be OK. I don't understand it, and it's leaving a bad taste in the community's mouth," Garth says. (Gersh claims it was a former MUFI partner who approached Garth.)

That was Garth's first impression of MUFI, and the relationship hasn't improved since. She tells us that she isn't interested in an agrihood, and she's concerned with how MUFI is attempting to take over land. She considers it "squatting," and alleges that Gersh also tried to take over private lots in the neighborhood. In one incident, her neighbor arrived home to find that Gersh had covered his yard with black tarps and dirt, Garth says. The neighbor ordered Gersh off his land.

It's these sort of moves that sources say raise lasting suspicions. When we spoke, Gersh noted that MUFI attracted a couple from Seattle who bought a historic house and spent $400,000 to renovate it. Asking longtime residents to sell their homes, then boasting about attracting wealthy out-of-towners is perhaps not the best look.

Another Gersh-related flashpoint is a few blocks north of the farm, where Vanguard is planning a 130-unit mixed affordable and market-rate housing project. Turner, Vanguard's executive director, tells Metro Times that Gersh purchased two properties across the street from the site. He doesn't own any other land in the North End, and Turner says she suspects he bought the parcels because of their proximity to Vanguard's project. Local law grants him a legal right to object during the rezoning process.

Turner and others charge that Gersh is against the development because it doesn't fit with his agrihood, and she characterizes Gersh's move as the latest in a series of ongoing "attacks" on Vanguard. She says those are rooted in a desire to control the neighborhood.

"Privilege plays a very big part in this," she says. "They act like they're just entitled. The North End is not empty land that they can come and colonize and shape into MUFI's vision."

Gersh takes a different view, however, and charges that Vanguard is the aggressor, while criticizing its leadership for not living in the neighborhood. He claims he bought the land before he knew of the plans, and also questions whether affordable housing is really effective as it doesn't lead to home ownership.

As for Garth's concerns: "Ette is not representative of anybody," Gersh tells us.

He adds that he's aware that some people view his aggressive pursuit of city-owned land and other property as "entitlement," and such charges have been leveled in multiple settings. But he says he has no choice if MUFI is to survive.

"This has nothing to do with being entitled," he tells us. "I cannot in good conscious invest resources into a space that is on a foundation that's so fragile."

Community support

When we met at his home, Gersh pulled out enough land use and parcel maps to put most city planners to shame. He referenced each as we talked about the agrihood. He's organized, he has a master plan, and he's methodically executing and tracking it. And this is the part of MUFI's mission that got Gersh most excited while we talked.

"We're the most active force in this location driving development. We already are an agrihood ... because that's what the city said they wanted. They wanted blighted houses rehabbed. We've done that," he says, pulling out a color-coded parcel map he created that tracks MUFI's and others' investment. "Here are people who would say, 'I would not have been here if this nonprofit didn't exist' ... so that was our initial, 'Alright, this is an agrihood.'"

But there's more to it.

"MUFI is a brand. I think MUFI started to cater to addressing structural inequalities in the food system, but as our understanding of the larger social context and social challenges grew, so too did our approach toward it, and we've branched into this rethinking of the urban living experience," he says. "As an entity that genuinely loves convening a large number of global brands and stakeholders toward a hyperlocal effort, I think [MUFI] is very uniquely positioned and has an opportunity to do so."

Though it's this type of thinking that attracts some criticism, it also attracts praise, including some from Mike Hammon, CDO of the Platform, a development firm involved in multiple large projects throughout Detroit. He's renovating a home in the agrihood, and applauds what Gersh is creating.

"I like the size and scale of [the development], as it's manageable. You can see across it, you can see around it. There's green space that has a use, and it's different," he says. "Sure, you can buy a house next to a park or golf course, but I don't know too many places where you can buy a house in an urban setting next to a farm."

Joanne Warwick, a North End resident and attorney who has lived or worked in the North End at different periods since the mid-1990s, similarly says that the farm is a "sanctuary" and a positive for the neighborhood. And Roger Robinson, who has lived in the North End since the 1970s, finds MUFI to be "an asset."

When asked about criticisms of Gersh, Robinson says that discussions of colonialism, for example, aren't true, and much of the disagreements in the neighborhood are a "pissing match" between Vanguard and Tyson.

"Sometimes he engages his mouth before he engages his mind and does things that aren't necessarily prudent," Robinson tells us. "But that doesn't change my general view of the project and what I believe is his good faith and intentions."

But others see the situation as part of the larger discussion around food security and poverty.

"This scenario belies how problematic the philanthropic industrial complex is, and how organizations like MUFI pose as false prophets, albeit well-intended ones," Bernardo says. "POC-led models like D-Town, Oakland Avenue and Feedom Freedom differ because they better understand the structural and historical inequities perpetuated by the dependency on charity."

"These ongoing issues are exasperated by disillusioned white-led orgs like MUFI that profess that simply creating more access to food is the answer to alleviating chronic hunger and poverty," he continues. "In actuality, they're merely sustaining the status quo and the structural inequities of power that characterize it. In a majority city of color, a predominantly black city like Detroit, 'Columbusing' is a huge issue that further adds insult to injury."

Part of the solution, Bernardo adds, is for funders and in-kind volunteers to "divest from charity programs and invest into work that actually shifts power and creates long-term structural change."

Similarly, Turner sees the situation as one that Detroit's issues facing longtime residents across many of the city's neighborhoods.

The fact is, there's a lot at stake for everyone involved.

"It's not just a disagreement about 'Build this here or build that there' — it's about race, class, power, and money," Turner says. "Real estate is how people become millionaires. It's a way that you can make a lot of money, and I hope that people understand it's not just a beef between Vanguard and Tyson."