John McLane guides his dirt-caked crew cab pickup along the dirt and asphalt roads of Osceola Township. A former surveyor who worked for the oil and natural gas industry for 30 years, he knows these back roads well enough to show where they intersect with the marshes, lakes, and streams that lead into the Chippewa and Twin creeks.

He stops every few miles or so to point out another waterway to his passenger, Peggy Case, board president of Michigan Citizens for Water Conservation. McLane joined the board of the organization to oppose food giant Nestlé's efforts to pump more groundwater out of the county, and as he points out inconsistencies between Nestlé's permit application and his fact-finding, you'd practically need a diamond-tipped drill to cut through his sarcasm.

He hops out of the truck on Eight Mile Road where a cross culvert pipe flows underneath into a swamp that joins the Chippewa. "We'll each estimate how much flow there is, and then I'll tell you what Nestlé says," he proposes.

"See that water down there?" he says, pointing to a squashed pipe leading into the field. "What's the flow per minute? I've got an idea in my mind."

Case steps down into the "swamp," which is not all that wet, in fact, and looks at the rust-colored water pooling in front of the pipe. She says it looks like zero flow. In fact, the water is so placid that a bug crawls along a twig that sits under the surface — and then defiantly turns upstream.

"They're saying that's 195 gallons a minute," McLane says. "I'd say that's exaggerated."

Less than a mile to the west, McLane points out a nameless but picturesque creek running under the road behind a homestead, ambling in a zig-zag fashion.

"To me, this looks more like 195 gallons per minute," he says. "You know what Nestlé's numbers say? They say 2,058 gallons per minute. That means you couldn't hardly stand in there without it knocking you flat."

As Case ambles down to inspect the creek bed, he mock-warns, "Don't stand down there or it'll knock you flat on your ass!"

Looping back across Seven Mile Road, he finds where Twin Creek passes underneath, impounded on the upstream side by a failing weir. He estimates the surface of the water is down a few feet, and points out a stand of cattails that wouldn't be able to set down roots in what used to be a lake.

"This is evidence of a drawdown that they don't want to admit to, because this has occurred since 2001," he says. "That was a lake! And they've drawn it down enough where you're back to the original channel."

For almost three hours, McLane shows off dry escarpments where springs used to flow, and anemic creeks that are too warm and lazy for the brook and brown trout that thrived there 15 years ago.

He even notices the change farther downstream, in the city of Evart, where Chippewa Creek dumps into the Muskegon River. "I did a survey for Shore Nursery right there in town," McLane says. "It's right by the well head for Evart. You couldn't walk in that swamp. It was wet. This was in 2000, before Nestlé charmed these folks. Now you could walk in it with your street shoes."

"If you calculate out 400 gallons per minute, it's a lot of water over a year."

tweet this

The battle of the 'Sanctuary'

The story of how Nestlé, specifically Nestlé Waters of North America, became involved in pumping water out of Michigan started almost 20 years ago. As some tell it, after facing pushback from trout fishers in Wisconsin back in the 1990s, the international food company began looking at Michigan's Lower Peninsula, particularly in Mecosta County, which borders Osceola County to the south.

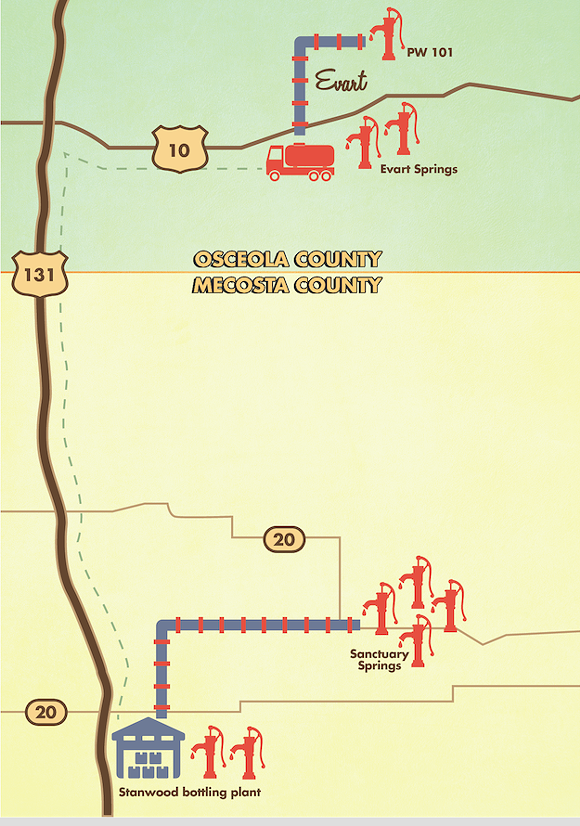

The company settled on a spot in Morton Township called Sanctuary Springs, near the Dead Stream. Nestlé filed the appropriate permits with the Michigan Department of Environmental Quality to drill four high-capacity wells, pumping 400 gallons per minute (GPM) or 576,000 gallons per day. It also built a pipeline to a plant in nearby Stanwood, where the water would be bottled under Nestlé Waters' Ice Mountain brand.

In 2001, Michigan Citizens for Water Conservation sued Nestlé Waters over the takings, embarking on a lawsuit that would result in a landmark 2003 ruling by Mecosta County Circuit Court Judge Lawrence C. Root.

By most accounts, Root was unlikely to sympathize with a citizen-run nonprofit environmental group. After Nestlé spent millions of dollars building all that infrastructure, would a fiftysomething conservative county judge make them stop pumping?

But as the MCWC's lead counsel Jim Olson, now of Olson, Bzdok, and Howard law firm in Traverse City, recalls, "He was conservative with ethics, because he didn't like the fact that Nestlé wasn't honestly representing what turned out to be serious harm to a stream, lake, and wetlands."

The ruling was probably the most closely watched in the history of the county court, and it was delivered in conversational prose that can be read by a layperson. The judge, himself an avid canoeist, angler, and outdoorsman, found the damages to the river would include warming harmful to existing species, excess nutrient loads and shrinking channels, and an impaired ability for upstream wetlands to filter water, control erosion and flooding, and provide important habitats for wildlife.

In November 2003, Root ruled that Nestlé's Sanctuary Springs wells caused substantial harm, were unreasonable under groundwater law, and violated the Michigan Environmental Protection Act. He ordered Nestlé to completely stop pumping water from the Sanctuary Springs site.

It was an unexpected legal rebuke. Nestlé Waters spokesperson Deborah Muchmore blasted the ruling as "quite extreme" and "very unwarranted."

One of the researchers who watched the case closely was Mark Luttenton, a professor of biology and associate dean at Grand Valley State University. He points out that while monitoring flow downstream can paint a favorable picture of a groundwater extraction operation, it's often upstream areas that bear the brunt ecologically.

"If we lose large segments of those upstream tributaries, then do we potentially lose the nursery habitat that's pretty critical to those juvenile trout and other fish species?" Luttenton says. "And I don't think the DEQ or DNR ever spoke to that issue. They seemed comfortable looking at kind of the system in total, especially farther downstream, which is where my understanding is they typically do their flow-measurements to determine potential impacts."

Nestlé naturally appealed Root's ruling, and Michigan Citizens for Water Conservation found itself fighting a drawn-out legal battle with the food conglomerate. In 2005, an appeals court upheld Root's findings of environmental harm, but ruled that a "balancing test" must be applied between "riparians" (area residents who enjoy surface and groundwater use) and Nestlé. Nestlé appealed that ruling as well, but the Michigan Supreme Court remanded the case back to trial court, which modified the injunction to ensure protection of the water and to determine what level of pumping could be allowed.

Rather than dispute the matter in court, in 2009 Nestlé and MCWC reached an out-of-court settlement establishing a limit of 218 GPM in winter months and an average of 125 GPM in the summer.

"There are some people who'd say that Nestlé taking 218 gallons instead of 400 is a victory," MCWC vice president Jeff Ostahowski says. "Well, they couldn't have taken 400 gallons. They've almost dried the aquifer as it is."

Despite MCWC's "victory" in Mecosta County, Michigan's legislature stepped in to make allowances for future bottled water projects. In 2008, Michigan passed a weaker Great Lakes water withdrawal law that allows water to be shipped out of the basin as long as the container is less than 5.7 gallons and doesn't harm fish populations in Michigan's lakes and streams.

Attorney Olson says one of the most ominous turns in the case was the "balancing act" ruling, in which Nestlé argued that the economic promise of an out-of-state water extraction business could be "balanced" against the groundwater rights of other landowners and the people of Michigan.

"We, as a state, fell short in 2008 when we adopted our groundwater withdrawal law," Olson says. "We didn't look at the bigger picture of where we're headed."

Case puts it more bluntly. "This balancing act that was an open door for Nestlé," she says. "They could claim they were offering jobs and anybody could come in and put a straw in the state and say, 'This is for economic development.'"

As proof, they offer the example of what happened in neighboring Osceola County, where Nestlé had gone 20 miles up the road to court new suitors in the city of Evart.

Water City, U.S.A.

Readers of the Grand Rapids Press on Sunday, March 6, 2005, were treated to the ultimate feel-good story: Big things were happening with the arrival of Nestlé in Evart. The high school softball teams were getting 14 acres of new fields in the coming year, a new bullpen, and brand-new locker rooms a few paces from the field.

Superintendent Howard Hyde was quoted as saying, "I'm tickled. It's like Christmas. Our current fields are pretty nice but these are going to be better."

The "windfall" came courtesy of Evart's water, and the mayor's desire to sell excess capacity formerly used by a factory to Nestlé. The article noted that, "unlike in Mecosta County, there is little opposition to selling Evart's water for distribution elsewhere. Community leaders believe there may be a bonus down the road: a second Ice Mountain bottling plant and scores of new jobs."

Looking back on Nestlé's honeymoon with Evart, Olson says, "I think what happened was at that time the city was falling over backward to help Nestlé because they had contributed some money for new athletic fields, and promised that a utopian plant would bring lots of jobs, so at that point the climate was nobody wanted to go against the grain, so to speak."

Drawing on his memories of the Mecosta County legal battle, Olson continues, "My view is that Nestlé let that one go. They didn't get their permit due to Judge Root's decisions, so they ran up and started dating city of Evart, got the approval, and started hauling water out, which essentially made up for what they lost at the Sanctuary."

According to a Nestlé spokesperson, the company's agreement to purchase water from Evart pertains to two Evart wells that are disconnected from the city municipal water system. The company considers itself just another customer of the city, much like previous companies that had used city water for industrial applications.

Nestlé's Christopher Rieck says the company pays the same per-gallon rate for water as residents, including any rate increases. The original rate was 88 cents per 1,000 gallons. The current rate is $2.30 per 1,000 gallons.

Rieck also eagerly points to all the contributions Nestlé has made to the mid-Michigan city. "Nestlé Waters' 10-year-plus partnership with the city has resulted in many opportunities for continued investment in the city," he says — contributions to new ballfields, the replacement of aging water infrastructure, improvements to watershed protection through enhancements to the city's wellhead protection program, improvements to the city's well houses, educational programs, river cleanups, highway cleanups, and community events.

"We are proud of our partnership with the city of Evart, where we both share in benefit of supplying natural spring water for our Michigan operations, drawing from the talented workforce in the area and enhancing the quality of community life," he says.

To the ever-sardonic John McLane, such proud claims ring hollow. Continuing his tour, he asks, "How many communities of 2,000 people have two water towers and nine wells, with water lines heading way outside of city limits? What's occurred here are a lot of what I'd call 'sweetheart deals' between Nestlé and the city fathers of Evart. And it would have been nice to have been a mouse in the room when these deals were made. ..."

He adds: "Because I don't know where Nestlé ends and Evart begins."

He stops briefly at West Seventh Street and Lauman Road, just off Evart's main drag, to point out Nestlé's hauling station, where the water goes into tankers bound for Stanwood. Then he drives more than a mile, past Evart airport with its 4,185-foot runway, to a well straddling a rails-to-trails state park. It's outside of city limits.

Trying to think of something to compare Evart's water infrastructure to, he finally says, "Big Rapids has four wells, and Big Rapids is 10,000 people with a college. So do you see something odd there?"

Between the official pronounce-ments about "enhancements" to "infrastructure" and McLane's tour, it's hard to avoid concluding that Nestlé has basically given Evart a gold-plated water system.

"In exchange for their souls," McLane says.

Pushing to pump more

Years before Nestlé cemented its relationship with Evart, it was already looking for more spring water in the vicinity. In 2001, Nestlé built a well north of Evart near the SpringHill Christian Summer Camp. It stands there today, at the end of 500 yards of two-track south of Nine Mile Road, a quarter-mile west of 100th Avenue.

After operating at its baseline capacity of 150 gallons per minute, in 2015 it bumped up pumping to 250 gallons per minute. In late 2015, Nestlé requested permission to raise pumping to 400 gallons per minute, the water flowing through a three-mile pipeline with a booster pump to the hauling station in Evart. In application language, Nestlé has said "surface waters, wetlands, aquatic communities and other nearby users of groundwater will not be adversely impacted or impaired by the proposed withdrawal."

That's hard for professor Luttenton to swallow. "If you calculate out 400 gallons per minute, it's a lot of water over a year: into the hundreds of millions of gallons per year," he says. "For me, from a biological standpoint ... I have a difficult time being able to come to that conclusion that there won't be any impacts at that point."

In fact, when Nestlé made that request, the company ran into a bit of light trouble with something called the Water Withdrawal Assessment Tool, a computer modeling program that was part of the 2008 revamp of the state water laws.

The program is designed to determine the potential impacts groundwater extraction might have on nearby rivers and streams. Olson points out that MDEQ notified Nestlé that the Water Withdrawal Assessment Tool had determined that pumping at 400 gallons per minute would have an adverse effect. When it ran the numbers on Dec. 4, 2015, it gave the plan a D — the lowest grade possible.

Nestlé got around this by requesting a site review, and the state department overruled the model's assessment, calling the program "overly conservative." When asked by a reporter how the failing grade wouldn't apply, Jim Milne, the shorelines unit chief of MDEQ's Water Resources Division, said it's not uncommon for staff to overrule the computer. The program had been run 350 times between July 2015 and July 2016: Of those, 227 earned passing grades; the other 123 were authorized by site review.

Such statistics suggest the Water Withdrawal Assessment Tool is overruled whenever it offers a failing grade.

It is widely acknowledged that the computer model is a conservative one: It presumes the aquifers don't have protective layers of clay to insulate their impact on nearby groundwater.

And yet Milne agrees the aquifer under PW 101 is glacial sand and gravel.

"We look at available information," Milne says. "It's not just the geology, although in this case it is an unconfined aquifer, but when we looked at the aquifer pumping test data. ... The aquifer has a higher storage capacity than what the tool had assumed."

Milne says MDEQ was able to arrive at these new determinations thanks to pumping test data Nestlé provided from 2001, when the well was first drilled.

In other words, beginning in late 2015, Nestlé was trying to gain approval to pump 400 gallons per minute from its PW 101 well. MDEQ seems to have carefully walked the company through the approval process, sweeping unfavorable assessments out of the way based on 15-year-old data.

On Jan. 5, MDEQ granted Nestlé permission to raise pumping to the magic number of 400 gallons per minute. But there was still one hurdle to get over before a permit could be placed in Nestlé's hands: Section 17 of the Michigan Safe Water Drinking Act. Nestlé submitted an application package for approval in July 2016. And before finally issuing a permit, it's customary for MDEQ to offer the people of the state a chance to comment on such decisions.

And the news that the comment period was about to end might never have been widely publicized if not for an eagle-eyed reporter.

That journalist was Garret Ellison of MLive, who jolted the leadership of Michigan Citizens for Water Conservation with the news that the comment period would expire in less than a week.

It turns out that the state's Department of Environmental Quality had chosen to notify the public of the comment period in an obscure departmental calendar not widely read beyond the agency's staff.

It's the kind of move that rankles the nonprofit's old attorney Jim Olson.

"They get the thing approved for the withdrawal back in January. How come nobody knew about that?" he says. "Why wasn't this public knowledge last fall in 2015? Or after the site-specific review in January?"

The volunteer-run nonprofit certainly wasn't spoiling for a battle. In fact, it had just paid off a million dollars' worth of legal debt after 12 years. But the optics of publishing a public notice in a mostly internal calendar raised the group's ire, and they began a feisty campaign to write the department, and to demand extensions on the comment period.

So far, that crusade has paid off. The comment deadline has been extended to March 3, 2017. And MDEQ's Carrie Monosmith says her office has so far received 13,811 emailed comments, more than 100 phone calls, and plenty of letters. She says her staff will have to be supplemented with interns in the new year to help sort through it all. And she says she has yet to see a single comment that's favorable about Nestlé's plans.

But that doesn't mean the permit won't go through. "They never deny a permit," Case says. "That's the job of the DEQ is to permit. The money that they function off of comes from permits. The permit has already been written, it just hasn't been delivered to Nestlé yet. They had no intention of denying it, until people started to raise a stink about it."

Case believes many of the problems with the department date back to when it was separated out from the state's Department of Natural Resources. Indeed, when you look at the department's guidelines as posted on a state government web page, they are asked to do the seemingly impossible: To ensure a healthy environment while being "partners in economic development."

Even now, with the cat out of the bag, the department is still falling behind in other respects. When MDEQ posted Nestlé's application online in November, Olson called and wrote them to notify them that they hadn't posted the figures, without which it's impossible to fully understand the application. That was six weeks ago, and the application still appears online with no illustrations or maps.

"There are all kinds of flaws in that permit," Case says. "There are land issues that need to be investigated. ... We're finding all kinds of flaws in the permit itself in terms of facts, the locations of things." With a hearty laugh, McLane says the application shows water flowing uphill, due to incorrect control data.

In fairness to Nestlé, and hydrogeologists, estimations related to water and aquifers are at times as much art as science. Judge Root noted as much in his 2003 ruling. McLane is also aware of the ambiguities, saying, "You know what hydrology is? A bunch of guesswork."

But the sorts of consultants brought in by companies like Nestlé only have to present a plausible scenario that sounds good.

What it all boils down to, McLane says, is that "they have done a lot of stuff to favor the idea that there's more water here than there really is."

And when, economically speaking, a community has something to gain or lose, that's often enough to convince people that no harm will be done.

Olson points to Nestlé's $36 million expansion of the Stanwood bottling plant, which will almost double the size of it. And he isn't alone in believing Nestlé intentionally expands its capacity before the necessary permits arrive to use it as an argument for why speedy approval is needed.

"Their pattern has been to expand their bottling plants and facilities, anticipating that they're going to get a larger volume of water," Luttenton says. "Then when they hit a roadblock, they use that financial investment and the potential of losing jobs as leverage to improve their chances of getting larger amounts of water at each of their production sites."

That may not have worked with Root in 2003, but it's generally been a tactical advantage to expand your capacity in economically starved mid-Michigan and then claim it's Traverse City environmentalists who are holding good jobs hostage.

Rough water ahead

But Case believes that may be changing. "People in Evart are not as thrilled with Nestlé as they used to be," she says. "The people of Evart are feeling that they're not getting much out of this. They didn't get a lot of quality jobs. There are a lot of people who are not so happy."

In fact, Evart is kind of on the decline. The same global forces that have brought Nestlé to town have swept away much of the manufacturing. Recently, the town even lost one of its major employers, a local dairy.

Complaints about what Evart-area residents have gained aren't the only problems looming for Nestlé. Neighbors are angry about a booster pump that has to be built into the three-mile pipeline, and the permit for that job was tabled at a recent township planning commission meeting.

And when it comes to compensation, the state gets little, at most a few thousand dollars in application fees. Other than the money Nestlé pays to Evart for being a regular customer, Nestlé has essentially pumped billions of gallons of water out of the state — and paid almost nothing.

In a decade, from 2005 to 2015, the company has withdrawn an estimated 3.4 billion gallons of water from its well fields. If you were to lay down the 5.2-gallon containers on their sides, they'd stretch from New York to Los Angeles — almost 70 times. All for a few thousand dollars in application fees.

And in light of crisis situations downstate, and even as far as Standing Rock, such takings resonate all the more loudly.

"This is particularly unconscionable when we're dealing with water shutoffs in Detroit and polluted water in Flint — and Nestlé's making a profit off the water in Michigan that should be part of the commons, it should be available to the people who need it," Case says. "They shouldn't have to buy it in bottles. Those people who've had their water shut off in Detroit should be drinking water from the aquifers that are part of the commons, and instead it's being privatized and shipped out of the watershed. It's just ridiculous."

"There is a disconnect here," Ostahowski says. "Nestlé is one of the largest food organizations in the world, and what they want from Evart is 400 gallons a minute. They will have to pay $200. That 400 GPM translates into 210 million gallons a year. So they're paying the state a whole dollar for every million gallons plus.

"Now you take that and you say to poor people in Detroit you've been disconnected for how long now for not paying for a few thousand gallons of water? There's a serious problem here."

In fact, at a meeting held Dec. 11 at the Evart Methodist Church, about 50 citizens of the township showed up to voice their concerns about Nestlé. Some local residents even expressed broad sympathy for downstaters. As reported in the Big Rapids Pioneer, a local business owner named Steve Petoskey said, "The people in this country need to learn about the people here in Evart as they learned about Flint. We need bumper stickers. We need to protest this."

Case hopes to be able to spread that message at a MDEQ hearing that will take place early next year in Big Rapids. But, like Petoskey, she feels the issue must be discussed more widely. Since the water is held in trust by every Michigander from Luna Pier to Iron Mountain, there should be hearings all over the state, and especially in Flint.

All that said, most of these "water protectors" speak of MDEQ staffers and the Nestlé people with a surprising civility that almost seems out of place.

"I do not hold anybody who's taken a job with DEQ responsible for their policies," Ostahowski says. "It's a problem with the people who direct that whole operation. ... And I like some of the people at Nestlé. They're nice people. They're doing their job. Nestlé's doing what corporations do. They're not saying, 'Let's go out and rape the environment today.' They're saying, 'Hey, we've got to get our production up! We want to grow!' and in business you grow or you die."

In the end, where Nestlé and other bottled water companies run into trouble is that they want to grow infinitely in a finite, closed system called Planet Earth.

"Everybody loves to say that Michigan has this huge untapped unlimited resource of fresh water," professor Luttenton says. "Yes we have a lot of groundwater, but more and more of it is becoming unusable for human consumption because of the high levels of contaminants. I think it's a real dangerous assumption to keep thinking we have this unlimited resource and not impose high levels of protection on that resource. "

"What does it mean to Michigan's future in a world water crisis, where world demand is going to exceed supply by about 30 percent in 15 years?" Olson asks. "We're headed down a really dangerous slope, and that slope is getting so steep, we won't be able to stop water going out of the Great Lakes."

For Case and her crew, fighting to protect Michigan's water is worth it. "Water companies are doing this all over the world. This is not just a Michigan phenomenon. They're sucking up water wherever they can find it and turning it into a huge profit."