Image use courtesy of Walter P. Reuther Library, Archives of Labor and Urban Affairs, Wayne State University

Mobs of white rioters on Woodward dragged black motorists from cars, tipped them over, and set them ablaze.

Last year, Detroit abounded with memories of the city during the tumultuous summer of 1967. Call it “the riot” or “the rebellion” as you prefer, but you must agree that the event was scrutinized as never before, the subject of a surge of articles, books, panel discussions, guided tours, museum exhibitions – even a bona fide Hollywood movie. The retrospective sometimes probed the boundaries of good taste, at times feeling like a gala event. But the best of it invited us to look past some of the traditional narratives about “the riots” and see things from another point of view.

Those myths clearly still loom large in metro Detroit, where many still believe the city's white flight officially kicked off at 9125 12th Street on July 23, 1967. Last year's long look back gave many people a chance to challenge that mythology, laying out the factual conditions that led inexorably to the disorder: grinding poverty, discrimination, and police brutality. Presenters took care to explain that you don't have to agree with arson or looting to understand what stoked the anger that inspired such acts. And if a year's worth of effort was able to dispel a myth or two in our deeply divided metropolis, we should be grateful that the occasion was exploited so thoughtfully and fruitfully.

Today, however, as we mark 75 years since the 1943 Detroit race riot, we wonder if maybe we might have devoted a bit more energy this year to remembering that episode. In a way, it's very much the same old story you've heard a thousand times before. It takes place while the country is at war. Riots in Detroit prompt local officials to request military intervention. The president declares Detroit to be under martial law and military vehicles roll down the city's streets in an occupation that lasts weeks.

But the war was against the Axis Powers, the president was FDR, and the majority of the rioters were white.

Related

Anxieties and hopes ran high all over Detroit. If many black Detroiters seemed more militant during the early 1940s, it's because they were. Many of them took the wartime propaganda at its word, embracing a “Double V” campaign of victory against fascism abroad and against racism at home. They had advocates at the NAACP, including future Supreme Court Justice Thurgood Marshall, who investigated cases of discrimination, or incidents of police brutality, which abounded in Detroit. The civil rights movement, most often considered a 1950s phenomenon, got off to a head start in Motown.

Among Detroit's white reactionaries, a kind of panic had set in, as they had just watched interracial labor unions win a five-year war with Detroit's automakers. Anxieties about integration often drove white workers and homeowners into the arms of demagogues. It didn't help that Detroit had long been a recruiting ground for the Ku Klux Klan and the lesser-known Black Legion. Or that radio listeners tuned in to hear the anti-Semitic broadcasts of Father Charles Coughlin of Royal Oak, or the tent revival-style sermons of Southern fundamentalist J. Frank Norris. Least of all that many newcomers were Southern hillbillies who'd always viewed white supremacy as 100 percent Americanism.

This simmering conflict erupted in hundreds of flashpoints across metro Detroit, ranging from individual scuffles on streetcars to massive hate strikes when black workers were promoted, or even small-scale riots, as when black residents moved into the Sojourner Truth housing projects in 1942. In truth, the Detroit riot was only one of a series of riots that swept through the country in 1943, from New York to Los Angeles. But it was the worst of them all, and the one that had been most widely predicted.

The riot began on Belle Isle on a hot summer Sunday. Tens of thousands of Detroiters, black and white, had sought relief from temperatures that had, by mid-afternoon, soared to 91 degrees. As the sun began to set, and as crowds jammed the Belle Isle Bridge headed home, a fight broke out between whites and blacks. Soon, hundreds of white sailors were running in to join it from the nearby naval armory, touching off a fracas that soon spread across Gabriel Richard Park. It took several hours for police to restore order.

But the evening's upheaval would flare up again almost immediately, driven by pernicious rumors spread by provocateurs throughout the city. White people heard that blacks had killed white sailors, or attacked a white woman. In a crowded black nightclub, a report that whites had beaten a black woman and thrown her baby off the bridge caused pandemonium. The false news did its dirty work quickly. By the early hours of the morning, on the all-black east side, mobs were shattering storefronts and attacking hapless white motorists. On Woodward Avenue, young whites accosted and attacked black patrons leaving the city's all-night movie theaters.

The Detroit Police Department sprang into action. It sent dozens of cars, cruisers, and wagons into the east side for an almost-24-hour spree of collective punishment. Michigan Chronicle editor Louis E. Martin grimly surmised that the department's riot plan was for “police to swarm into the area occupied by Negroes, disarm the residents and then proceed to outdo the Gestapo in killings and brutalities." Shouting racial epithets, beating up innocent pedestrians – including at least one man in uniform – police not only shot blacks in the back, they sprayed whole buildings with automatic gunfire. After a police beating, one black victim asked police to be taken to a hospital. “Niggers don't need doctors,” the cop told him.

Meanwhile, on Woodward Avenue and downtown, most police winked at the growing crowds of white marauders, who by morning had graduated to attacking unsuspecting blacks venturing onto the city's shared main thoroughfare. By noon they were pulling black straphangers off streetcars and bashing them into unconsciousness. Black motorists were snatched from their cars by white mobs, their cars turned over and burned in the middle of the street.

Image use courtesy of Walter P. Reuther Library, Archives of Labor and Urban Affairs, Wayne State University

Detroit firefighters respond to a car fire on Woodward Avenue.

Some police were decent enough, and did what they could to quell white violence and protect black Detroiters. And many Detroiters, white and black, took the risk of wading into the violence across the color line to rescue victims from certain death. But there were not enough of them to stop the situation from spiraling out of control.

City and state officials were little help. Detroit's playboy mayor, Edward J. Jeffries Jr., largely frittered the day away in meeting rooms, either waffling on whether to call in the U.S. Army or, along with Gov. Harry Kelly, trying to hammer out a “modified martial law” that wouldn't supersede city and state functions. These talks continued all afternoon, into the evening, until almost nightfall, even as they were interrupted by white mobs rampaging on the street below.

By evening, those throngs were 10,000 strong, with some of the worst violence between Mack and downtown. That's where crowds were bold enough to begin challenging the one thing Detroit's police believed worth defending: the color line at John R Street. Great masses of people spilled up and down John R, swelling around Watson Street and Edmund Place. Through it all, police used nothing stronger than tear gas on the crowds. But when blacks gathered behind them in defiance of the white rioters, police turned and shot at them.

Balked by police, the crowd pushed down John R. One eyewitness said a police officer led them down Brush Street, closer to the heart of Detroit's downtown black business district. At Adelaide Street, they set a house on fire. At Vernor Highway, they threw bricks at black apartment houses and shouted epithets. Just down the block, police exchanged gunfire with a black attacker outside the Vernor Highway Hotel. That's when the law enforcement massed at the corner of Brush and Vernor trained its spotlights on the hotel, shot it full of tear gas, and sprayed the building with 1,000 rounds of ammunition. Police then cleared the building, and stole cash, liquor, and other valuables from the residents while they were detained on the sidewalk.

As the violence reached this climax, the mayor and governor had finally found conditions agreeable to a declaration of martial law, and the U.S. Army arrived and largely ended the bloodshed by calmly but firmly pushing white and black rioters off main roads without firing a shot. By 11 p.m., Woodward Avenue had been cleared at bayonet-point, and the city was restored to relative order by 2 a.m.

The riot had raged for almost 24 hours, claiming millions of dollars in damages, hundreds injured, and 34 dead – as well as 1 million man-hours of lost industrial production. But it took its most brutal toll on black Detroiters. Not only did white gangsters probe their neighborhood from both sides all day long, the city's police treated it as a free-fire zone. Of 25 blacks killed, 18 were shot by police, many in the back while fleeing, or for making an insulting remark – or for nothing at all. Police arrested more than four times as many blacks as whites, though blacks were just 10 percent of the population.

When confronted with demands for an independent grand jury to investigate the riot, Detroit's white leadership, conservative and liberal, closed ranks. The blame for the riot lay, they said, with aggressive black leaders and the troublemakers at the NAACP.

Detroit Police Commissioner John H. Witherspoon said it only made sense that police arrested so many blacks, since he said they were responsible for 71 percent of the crime in the city. “If the NAACP would devote the same amount of time to educating its people to be good citizens and respect the law as they devote to alleged charges of discrimination and police brutality," he said, "they would be a helpful organization instead of a detrimental one.”

This consensus satisfied anxious white homeowners, the police, and helped win Mayor Jeffries another term, freezing out the candidate supported by labor and black leaders. Meanwhile, police repeatedly failed to apprehend many of the white rioters caught in the act by newspaper photographers.

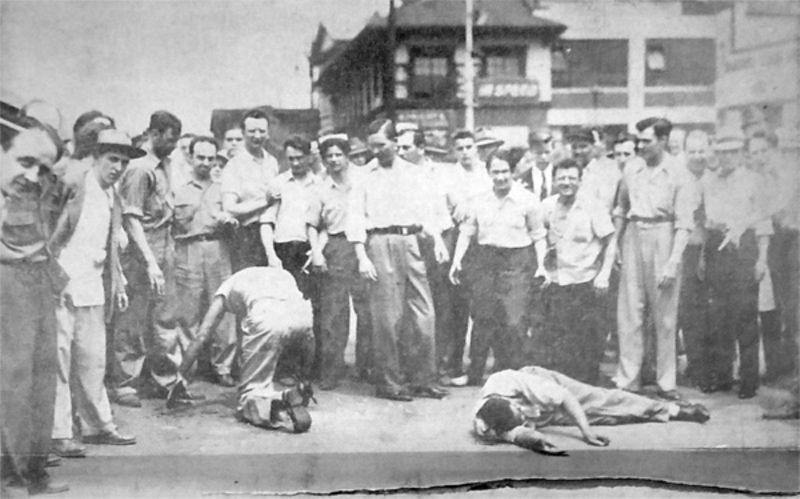

Unidentified clipping, 1943 riot folder, Burton Collection, Detroit Public Library

White rioters swagger over their black victims in front of a gas station at Erskine and Woodward in this newspaper photograph.

Yes, it appeared that many things were up for grabs in wartime Detroit, but the color line wasn't going to be one of them. The outcome cemented race relations in Detroit for another generation. Members of Detroit City Council would speak approvingly of segregation into the 1960s. The outcome also meant no reformers would tamper with the Detroit Police Department whose officers had conducted themselves like gangsters.

The aftermath also dealt a serious blow to black hopes for interracial fellowship. It's no coincidence that, after the race riot, black nationalism in Detroit enjoyed a resurgence that lasted into the 1960s. Michigan Chronicle editor Louis E. Martin diagnosed the situation in the riot's wake, writing: “We better be frank about this. The race riot and all that have gone before have made my people more nationalistic and more chauvinistic and anti-white than they ever were before. Even those of us who were half-liberal and were willing to believe in the possibilities of improving race relations have begun to doubt – and worse, they have given up hope.”

The feeling of settling in for a long and unfair peace seemed to motivate one Detroiter who wrote to Mayor Jeffries, “The thing that amazes me is why the Detroit Police was so quick on the trigger in the colored neighborhood and was so dumb and helpless when Negroes' cars were being burned out from under them. … I once was proud of the city officers but from now on I'm teaching my kids their real purposes toward our race. I think some of them are rotten through and through. ...”

It would be easy to merely suggest that the 1943 riot planted the seeds of what happened in 1967. In fact, the narrative of post-1967 Detroit – that Detroit finally elected a mayor who could reform the mostly white police force and make it more representative of the city – offers a tempting fable of good old American redemption.

But there's something about the 1943 riot that, in all its ugliness, is profoundly American. Yes, it's short on redemption, and it embodies the worst of who we are. It casts members of the Greatest Generation as the villains of the story. It complicates the mythology of World War II as an unblemished fight against white supremacy. It amply illustrates longstanding and often dismissed fears of police brutality among African Americans. And it offers an exceptionally revealing look at white violence in the American Midwest, especially among police.

Yet that's precisely why it should be remembered. As a sage once said, “Those who do not learn history are doomed to repeat it.”

Given how few know what happened 75 years ago today, that's a terrifying prospect.

Michael Jackman is working on a book about the 1943 Detroit race riot.

Stay on top of Detroit news and views. Sign up for our weekly issue newsletter delivered each Wednesday.