My roommate's alarm buzzes. It's the second weekend of my first year at the University of Michigan, and I could swear it's still the middle of the night. I look out our dusty window to the East Quad courtyard; students in spirit gear are packed into every available space. I smell takeout from the nearby Ray's Red Hots and hear the Chainsmokers' "Closer" blaring from an old-fashioned boombox.

"Happy game day!" my roommate chirps, hopping out of bed.

I glance at the clock. It's 7:35 a.m.

It's no secret that Ann Arbor is one of Michigan's buzziest cities. U-M's home base is an ever-growing hotbed for tech start-ups, yoga studios, and kitschy coffee shops. According to 2016 U.S. Census data estimates released in March, Washtenaw County led southeastern Michigan in population growth last year.

But there is an elephant in the room: As the university celebrates its 200-year anniversary, state residents are reminded that the institution once called Detroit home. The bicentennial celebration prompts the question: What could have happened if U-M had stayed in Motown?

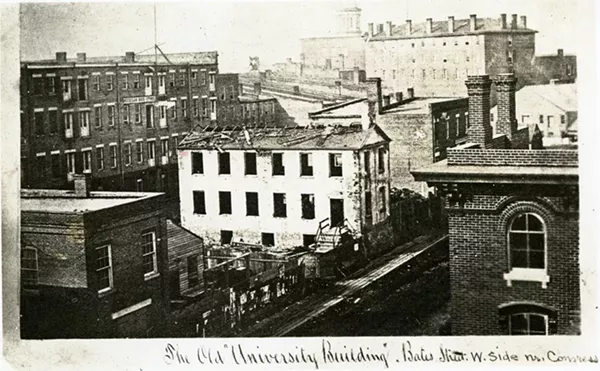

Michigan became a territory in 1805. The University of Michigan was founded by Augustus Woodward, Reverend John Monteith, and the Rev. Gabriel Richard on Aug. 26, 1817 as the Catholepistemiad, or University of Michigania. Its first building was erected on the corner of Bates and Larned streets in downtown Detroit on land conceded to the university by several Native American tribes through the Treaty of Fort Meigs.

"There's only about 4,000 people in the entire state, and so there isn't an awful lot going [on]," says Brian Williams, the lead bicentennial archivist at U-M's Bentley Library. "Detroit's the biggest city out of all of that, and it's really populated by traders, trappers, missionaries just passing through, and there's a pretty big Native American population. ... So they settled on Detroit. I think it's just the fact that it was the biggest thing going at the time."

But just 20 years later, in 1837, U-M moved to its current residence in Ann Arbor.

The city was much different back then, with a population of just a couple thousand people. Williams says land speculators offered a package of land to entice the university to move there in 1837. The university had two options: 40 acres, or what's the core of the central campus today, and an area in the hills near the river. They opted for the 40 acres that are now central campus.

Today, it appears that the University of Michigan has provided Ann Arbor with a buffer against everything that Detroit suffers from: a falling population, a sputtering economy, poverty-driven crime, and neighborhood decline.

According to Larissa Larsen, an associate professor of urban and regional planning at the university, institutions as powerful as U-M can make even the most desolate areas desirable. She points to the University of Pennsylvania's impact on west Philadelphia and the University of Chicago's impact on Hyde Park.

"The neighborhood in west Philadelphia, there was terrific deterioration, and beginning in the '80s, there were a lot of efforts that partnered the University of Pennsylvania with community members or organizations, nonprofits, in an effort to improve the neighborhood — and selfishly, because they wanted their university institution to be desirable," she says. "You can measure the outcomes of what happened as far as new retail spaces, higher home values, reduced crime rates, new public amenities, and improved K-8 schools."

The same thing happened in Chicago. "Woodlawn was, is, a poor neighborhood, but because [the University of Chicago] wanted to continue to attract good students, good faculty, and maintain the University's position, they invested a lot of money into it," she says. A 2015 memorandum between the University and the city of Chicago pledged to invest $750 million in the Hyde Park area over the next three years.

Sure, Ann Arbor was never in shambles, but it didn't have a chance to be; U-M moved there just 13 years after its creation.

Today, it appears that the University of Michigan has provided Ann Arbor with a buffer against everything that Detroit suffers from.

tweet this

"U-M drives so much; it's such an economic engine to [Ann Arbor], but it fosters all these other little research innovations around it, its connection to the auto industry, just all of the research, technology, innovation, all that's going around with it, and what it does for the employment," Williams says. "If you look at the staff members, some 30,000 staff members. You've got the [U-M] hospital employees; that's a huge employer for the city."

Yet it's not all peaches and cream in the college town. According to The Michigan Daily, the median rate for rent in Ann Arbor increased 14 percent from 2010 to 2015, and now sits at about $1,075 per month, though the amount of high-density housing area has also risen by 32 percent.

What, then, would Detroit have done with a double-edged sword like the University of Michigan?

Today, there are 44,718 students on the Ann Arbor campus. The University is home to one of the largest health care complexes in the world, along with one of the most extensive university library systems in the country. Though we will never know for certain whether a maize-and-blue Detroit would have been better or worse, we can guess that it would have been vastly different.

Larsen cites the book Detroit Resurrected by Nathan Bomey, which discusses Detroit's bankruptcy. While the city suffered from government mismanagement, Bomey argues that the situation could have been helped by a "constellation of institutions."

"Would [U-M] have saved Detroit? I don't know we can say that ... But it would have had a big impact," says Larsen. "I think you would have seen an impact on transit; with students, we generally like to make sure there are options that aren't just [cars]. Also, too, the housing quality adjacent to where the university is. I look at Wayne State as a bit of a stable point in the city. I think a U-M would have been much bigger and more pronounced."

In Williams' mind, a location in Detroit would have provided students with more opportunities in the auto industry and the arts.

"If [U-M had] stayed in that current location, I think that would have been geographically constrained, so I'd imagine the University would have expanded," he says. "And [I don't know] whether it would have expanded to the same degree, they might have been bound by other land developments in Detroit, but you can see that maybe the connections to the auto industry would be even tighter, just being situated within all of that."

After the tailgating festivities have died down, I decide to call it a night. When I return to my dorm, I peer out the same courtyard window. Students continue to fill the space, laughing and dancing, celebrating a well-deserved win. Someone topples over; her friends bust out laughing, running to her aid. It is 1 in the morning.

It's just another night in Ann Arbor, filled with a special kind of bustle that almost belonged to Detroit.

Tess Garcia is an editorial intern at Metro Times.