Looper| B+

So close to being a great movie is Looper that I want to go back in time and chat with writer-director Rian Johnson (Brick, The Brothers Bloom) about the parts of the film that come up short.

When it comes to time-travel thrillers, Terry Gilliam's 12 Monkeys looms large. And not just because, like Looper, it stars Bruce Willis. The 1995 movie, based on Chris Marker's La Jetee, was the complete entertainment package: humane, tragic, exciting, surprising and comical. More importantly, it was science-fiction film that didn't define itself through gee-whiz production design and digital effects instead of character and story (ironic given Gilliam's résumé).

Looper has many of those same instincts and ingredients, yet struggles to make them whole. Johnson has crafted a smart and suspenseful tale of identity and redemption but, unfortunately, has placed at his story's center a protagonist we never truly get to know.

Joseph Gordon-Levitt is Joe, an assassin who lives in the crumbling urbanity of 2042 Kansas City. Working for the mob, he kills and disposes of people that have been sent back in time by his employers. It's good-paying work, but he knows that one day he'll have to terminate his future self. The mob doesn't like loose ends. Can he do it when the time comes? The answer becomes moot when his 30-year-older self (Bruce Willis) manages to escape. This puts both versions of Joe in the cross-hairs of his boss (a casually wicked Jeff Daniels). Young Joe holes up on the farm of single mom Sara (Emily Blunt) and her 6-year old telekinetic son, Cid (Pierce Gagnon). Old Joe hunts for the child that will eventually grow up to be the biggest, baddest mob boss of all. Can you see where this is going?

Johnson's cat-and-mouse thriller keeps the futuristic affectations believable as he deftly navigates through inventively staged action scenes and cerebral pretense. There are hover bikes, a few nifty weapons, and older model cars retrofitted with solar panels, but the world pretty much looks like a bleaker, poorer version of today. Smartly, he keeps the pace up and the dialogue sharp. In one cleverly self-referential scene Daniels berates Young Joe for his fashion sense, stating, "The movies that you're dressing like are just copying other movies. Be new." In another, Looper acknowledges the futility of explaining time travel mechanics with Daniels spitting, "Time-travel shit fries your brain like an egg," and Willis refusing to play along because, "... we'll just be here all day making diagrams with straws."

Looper's biggest narrative stumble, in an otherwise effectively plotted yarn, is Cid's telekinetic subplot. It's one thing to ask an audience to swallow time travel. It's another to throw such mental powers into the mix. Creating believable science fiction is tricky business, and the mantra of "less is more" is something Johnson should have taken to heart.

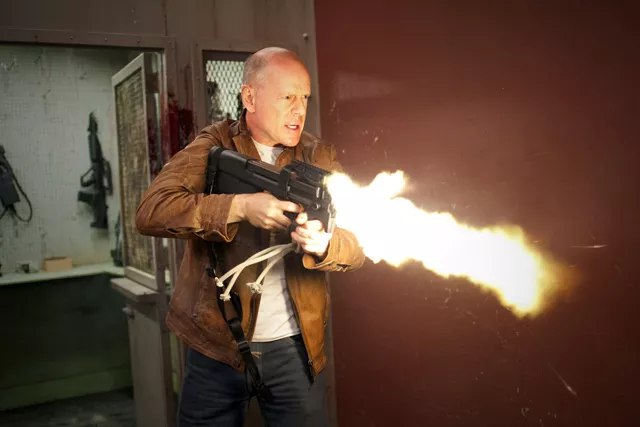

Still, he has a terrific cast to sell his more outlandish ideas. Willis delivers the same burned-out, sad-eyed machismo he's been peddling for the last decade, and it works perfectly here. Blunt brings layers of humanity to a character who says more than she's given an opportunity to show. And Levitt pushes aside his boyish charisma to adopt Willis' hard-nosed, smirky core. More than just an impression (and good make-up job), he convincingly portrays his older version's past self, the man before man.

But it's not quite enough. Johnson seems boxed in by his man-tries-to-kill-himself conceit. Levitt may be an effective precursor to Willis' haunted and homicidal Joe, but, emotionally, he never registers as his own man. His relationship with Blunt is more about potential than connection, undermining the film's half-hearted stab at romance. Worse, Young Joe is so tightly coiled we have a hard time feeling the impact of his final decision and, thus, Looper's tortuous ethical quandary.

Not only does Looper raise questions about how far people will go to protect their loved ones, it also asks whether someone can do good by doing wrong. What are consequences when a person decides to kill a child they believe is fated to grow up into a monster? To wrap a serious moral question in a futuristic shoot-'em-up is a noble and nifty idea, but you've got to make us care about the outcome. While there's no denying Johnson's intellectual ambitions, a little more heart would have given his film the punch it needs.