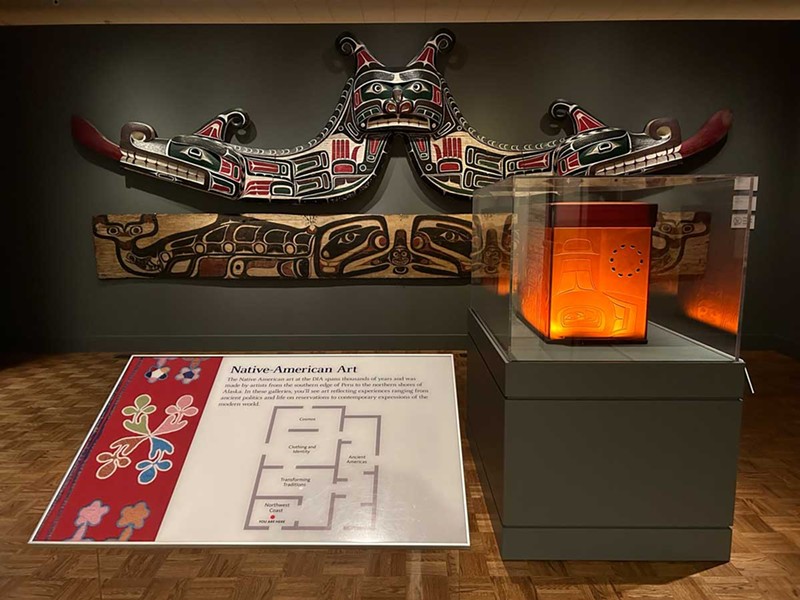

During a visit to the Detroit Institute of Arts in February, I noticed a section of the Native American Art exhibit was missing with signs that read, “Gallery work in progress. We are preparing something new for you. Come see in March!”

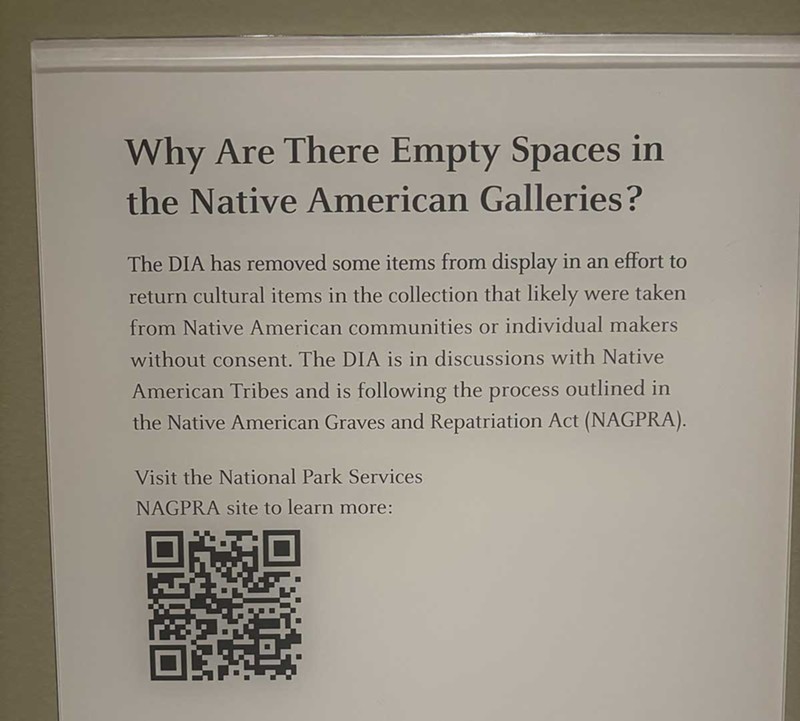

A new exhibit of contemporary Native American art had been unveiled in the DIA’s Cosmos Gallery upon a second visit. Next to it, a sign says the museum removed items that had been displayed.

“Why Are There Empty Spaces in the Native American Galleries?” the sign reads. It continues, “The DIA has removed some items from display in an effort to return cultural items in the collection that likely were taken from Native American communities or individual makers without consent. The DIA is in discussion with Native American Tribes and is following the process outlined in the Native American Graves and Repatriation Act (NAGPRA).”

The DIA tells Metro Times the NAGPRA notices were installed in the Native American Art galleries in early 2023.

Across the nation, museums have been removing items from Native American exhibits or dismantling them entirely in response to updated federal regulations that require institutions to obtain informed consent from Indigenous tribes, lineal descendants, or Native Hawaiian Organizations (NHOs) before displaying, possessing, or conducting research on culturally significant items.

A revised version of NAGPRA went into effect on January 12, 2024 with stricter guidelines for institutions to return human remains, funerary items, sacred objects, and objects of cultural patrimony to the tribes they originated from. Museums have five years to consult with tribes, update their inventories, and return the remains of ancestors and funerary objects.

NAGPRA isn’t a new law that suddenly appeared in 2024, however. It has been the federal law since 1990 and regulations requiring institutions to consult with Native American tribes went into effect in 1995. Unfortunately, as Chief Executive and Attorney for the Association on American Indian Affairs Shannon O’Loughlin explains, several loopholes in the previous iteration of NAGPRA allowed museums to get away with non-compliance.

“There was no definition of what consultation meant,” O’Loughlin says about the faults of NAGPRA as it was previously written. “So what we saw is, institutions who didn’t want to comply would simply send a letter or an email, and that’s all they would ever do to communicate with tribes. Then they would make their own determinations without true consultation.”

She adds, “The law has been in place for more than 30 years saying, you don’t have a right to these items. You’re supposed to be repatriating these items, but institutions haven’t done that... If you want to do an exhibit or you want to do extractive research and pull DNA out of my ancestors, you need to ask permission first because it’s native nations who are the primary experts of their cultural heritage and the rightful holders of these materials.”

In 2021, DIA Assistant Curator for Native American Art Denene De Quintal “encountered” the remains of 13 Indigenous ancestors and six funerary objects in a storeroom for the museum’s Indigenous Americas collection during a “comprehensive inventory,” according to transcripts from a NAGPRA Review Committee meeting on June 7-8, 2023. De Quintal joined the museum in 2019 after the position was vacant for nearly a decade.

The American Museum of Natural History in New York City removed two of its Native American exhibits completely following the updated regulations. The Cleveland Museum of Art and Chicago’s Field Museum of Natural History covered display cases with Native American items in response, and the Peabody Museum of Archaeology and Ethnology at Harvard University vowed to remove all funerary items.

The DIA has a history of consulting with tribes and has worked to return the remains of at least 21 ancestors and several cultural objects in its possession over the past several decades, including the ancestors discovered in 2021.

Despite a month of back and forth with the museum via email prior to the unveiling of the new exhibit, the DIA would not provide Metro Times with additional information on what items were previously displayed in the Cosmos Gallery “out of respect for the tribes.”

A representative for the museum wrote about the new exhibit, “This gallery has been planned for more than a year. The galleries have been installed since 2007, [and] the new gallery is a chance to highlight contemporary art and contemporary voices before a full reinstallation of all the galleries can be planned.”

The DIA told Metro Times it was consulting with local tribes and “[deferred] to them to share that information.”

“In our commitment to adhering to the Native American Graves Protection and Repatriation Act (NAGPRA), we have and continue to welcome consultations with Native American tribes,” a statement from the museum reads. “Consultation has been used in the recent past and will continue to be used by the DIA to determine what items are and will be on display. The museum will make every effort to ensure its compliance with the new NAGPRA regulations.”

I also observed in February that an item described as a “model of a Shaman’s guardian figure” from the Central Council of Tlingit & Haida Indian Tribes of Alaska had been removed from a display case at the DIA. A placard in its place notes “this item has been temporarily removed” and is dated August 1, 2022.

O’Loughlin says museums covering up and removing collections is a red flag that shows which institutions haven’t been compliant with NAGPRA all this time. O’Loughlin sat on the NAGPRA Review Committee from 2013 to 2015 and is a citizen of the Choctaw Nation of Oklahoma.

The DIA’s history of repatriation

At the June 2023 NAGPRA Review Committee meeting, De Quintal and other DIA staff received the committee’s approval to repatriate the remains of 11 ancestors and six funerary objects to Michigan’s Sault Ste. Marie Tribe of Chippewa Indians.

The museum needed approval because the 11 ancestors had been deemed “culturally unidentifiable,” an egregious term O’Loughlin says museums have used to claim they couldn’t trace the ancestors’ origin and, therefore, didn’t know what tribe to return them to. The other two ancestors out of the 13 that were discovered were determined to be affiliated with Michigan’s Upper Peninsula.

One of the updates to NAGPRA was removing the “culturally unidentifiable human remains” category.

“It’s a lie under the law,” O’Loughlin says about Native American ancestors being culturally unidentifiable. “Most of these institutions, the inventories that they’ve produced have plenty of information, including geography, to affiliate those ancestors with their nations. But, they determined that — because they didn’t consult [and] they just sent a letter — ‘I guess they’re not identified with anyone, so we’ll keep them.’”

She continues, “Harvard is a great example of this because, unless an ancestor was deemed affiliated, they would continue to do extractive DNA research and other types of research on human remains and cultural items even though they had no legal right to do so… So the new regulations are really important, not just because they’ve now defined clearly what consultation means, but they’ve also eliminated this concept of ‘unidentifiable.’”

De Quintal said at the June 2023 meeting that the DIA invited “43 Indian tribes, as well as the two Michigan State Historic Tribes whose aboriginal land includes Michigan” to the museum for consultation and “no one objected to a culturally unidentifiable determination based on a lack of evidence.”

According to De Quintal, after monthly meetings with NAGPRA representatives of Michigan’s Anishinaabe tribes and the Michigan Anishinaabek Cultural Preservation and Repatriation Alliance (MACPRA), the Sault Ste. Marie Tribe requested the remains be returned to them.

The DIA confirmed to Metro Times that the ancestors had been returned.

Marie Richards, who was the Repatriation and Historic Preservation Specialist for the Sault Ste. Marie Tribe at the time, was responsible for removing those ancestors from the DIA and bringing them to the Upper Peninsula. She now works for the federal government as a Tribal Relations Specialist.

“I made a trip from Sault Ste. Marie to [the] Detroit Institute of Arts that Wednesday before Thanksgiving,” Richards recalls to Metro Times. “I met with staff and was able to, under the language of the law, take possession [and] have stewardship, and [I] escorted those ancestors up to Sault Ste. Marie… It’s a culturally sensitive thing but we try to help them continue their journey back to the spirit world after having that disturbance the best that we can, and part of that is reburial.”

Richards explains that the Sault Ste. Marie Tribe is often the designated caretaker for “unidentifiable” ancestors in cases like these, as decided by the Michigan Anishinaabek Cultural Preservation and Repatriation Alliance.

“Sault Ste. Marie Tribe of Chippewa Indians is based out of Sault Ste. Marie, [Michigan]. It’s the gathering place, where on different occasions, bands of Anishinaabe from all over the Great Lakes would meet,” she says. “Because of that historical role that we played in our culture as the host to people from many nations, we continue doing that… Those ancestors do have a right to something, so it’s just a matter of figuring out how we can do that in a good way.”

Richards says the Sault Ste. Marie tribe has also received the remains of ancestors repatriated from Michigan State University in a similar situation where they were deemed “culturally unidentifiable.”

According to ProPublica’s Repatriation Database, the DIA has made all of the 23 Native American remains that it reported having to the federal government available for return to tribes. The same database reports that Michigan State University has made 100% of 544 ancestors and over 84,900 associated funerary objects it reported possessing available for return to tribes.

However, making the remains and funerary objects “available for repatriation” doesn’t always mean those ancestors and sacred items make it back home.

“That’s one of the problems that we tried to correct with the new regulations [is] that you don’t really know what actually happened or not,” O’Loughlin says.

After an institution submits a “notice of intent to repatriate” on the federal register, the affiliated nations then have to submit a request for repatriation, O’Loughlin explains.

“So there has to be that formal, ‘yes, please give these back,’” she says. “This signifies kind of an administrative return… but there’s no notice that will tell you if something’s actually been physically returned.”

On January 16, 2024, days after the NAGPRA updates went into effect, the DIA filed a notice with the National Park Service’s federal register to repatriate seven objects of cultural patrimony and four funerary items. These were reportedly removed from “unknown locations in Alaska'' and have been traced back to the Central Council of the Tlingit & Haida Indian Tribes. Some of the objects include a Gooch Shádaa (wolf headdress), a Weix’ S’eek Daakeit (sculpin tobacco pipe), a Xixch’ S’eek Daakeit (frog tobacco pipe), a Kaashishxaaw S’eek Daakeit (dragonfly pipe), and a bear tooth amulet.

The DIA confirmed that the Shaman guardian figure removed from display in 2022 (and whose space was still empty during our visit) is one of the items it intends to repatriate.

“The museum’s work on this gallery continues,” a DIA representative told Metro Times. “In addition to tribal consultations on the collection, items are often removed from display or rotated as is common in museums. As that continues more items may be removed from the galleries and may through the process established by NAGPRA. Out of respect for the tribes and their preference on how this process should be handled, the museum will not make an announcement every time this happens, but the work is ongoing.”

Four of these items are believed to have been placed “with or near individual human remains” as part of a burial rite or ceremony, and all were determined to have ongoing historical, traditional, or cultural importance to the Tlingit and Haida Tribes.

“The documents were published in January but the decision was made before that,” a representative for the museum said about the notice of intent to repatriate. “The process can take years from the initial consultation to the formal request from the tribe.”

Back in 2001, the DIA filed a notice of intent to repatriate a bear claw necklace of cultural patrimony from its collection. The necklace — made of 30 grizzly bear claws, glass beads, and otter fur — belonged to James White Cloud (1841-1940), a chief of the Iowa Tribe of Kansas and Nebraska. According to the federal register, the DIA purchased this necklace in 1981 from a man named Richard Pohrt of Flint. Documents and oral testimony show the necklace had passed through an Oklahoma pawn shop, Oklahoma’s Southern Plains Indian Museum and Crafts Center, and another man named Mildford Chandler of Detroit before landing in the DIA’s possession.

Judith Dolkart, DIA Deputy Director of Art, Education & Programs, told the NAGPRA Review Committee the necklace had since been repatriated to the Iowa Tribe of Kansas and Nebraska.

“[NAGPRA] is only 34 years old, and if everyone had followed it as they should have, the only issue would be new acquisitions. But unfortunately, that’s not the case,” Richards says. “With objects of cultural patrimony, that is the one where we’re seeing more changes in the federal law and that’s why many institutions immediately pulled objects they did not have consent for, or covered them. [The] DIA had already had such items not on display.”

Richards says the Sault Ste. Marie Tribe was invited to the DIA along with several other tribes to consult with the museum about patrimony objects in 2023.

“I’m very vocal about why consultation has to happen, why these conversations with tribes have to happen collectively,” she says. “There were several tribes present so we could talk with each other as well as interact with the items. It’s important for the institution to talk with the tribe and also for us to be able to interact with our colleagues who also want what’s best for the ancestors and those objects of cultural patrimony.”

According to transcripts from the June 2023 NAGPRA Review Committee meeting, the DIA submitted notice of having 10 “culturally unidentifiable” Native American ancestors in its inventory in the early 1990s that had been “removed from Detroit or the surrounding area.” After consulting with several of Michigan’s Anishinaabe tribes, Dolkart told the committee, those ancestors were returned in or after 2009.

She also noted that the DIA held monthly virtual meetings with Michigan tribes between October 2022 and April of 2023, who advised the museum on what items should be removed from display.

“Throughout those seven months, the tribes determined which images should be removed from the DIA’s website, which items should be removed from display, and which items the DIA collection staff should make available for examination during an in-person consultation,” she said.

At that same meeting, Veronica Pasfield, a NAGPRA Officer for Bay Mills Indian Community in Brimley, Michigan, commended the DIA for its efforts.

“I was involved in the Detroit Institute of Arts consultation and I just wanted to publicly state that I give a lot of credit to the Detroit Institute of Arts,” she said. “They and we were surprised to realize that the museum had some outstanding NAGPRA obligations, and the Detroit Institute of Arts really seemed to take seriously its federal legal compliance responsibilities, as well as the human rights imperative that Congress set forth when creating NAGPRA in 1990. And for any museum that’s listening or any tribe that’s listening, if you want an example of what is possible when you have the institutional will, the Detroit Institute of Arts, with the support of Jan Bernstein [of Bernstein & Associates NAGPRA Consultants] and her team, really stepped up in a way that was very admirable and, in my experience, quite rare.”

According to the Oakland Press, a ceremony to thank the DIA for its work returning Native American ancestors was held in February. At the ceremony, De Quintal was presented with a Healing Blanket and DIA Director and President Salvador Salort-Pons was given a plaque from South Eastern Michigan Indians, Inc., American Indian Health and Family Services Inc., and the Northern American Indian Association of Detroit, the Oakland Press reported.

In O’Loughlin’s eyes, closing entire Native American exhibits is taking the easy way out of a nuanced issue. Instead, she says, museums should do the work to consult with tribes so they can learn exactly what they have in their collections and display them accurately and respectfully.

“As we were all going into NAGPRA and institutions were often fighting against NAGPRA, the complaint was that all their shelves would be empty,” she says. “And what we found was that when true consultation actually happens between tribes and those institutions… they learn about the values of various and diverse native nations so that they can properly educate the public because that’s the mission of a museum anyway… They’ve only had information provided by an archaeologist or an anthropologist and it often does not include the primary experts, the original peoples where the items came from.”

She adds, “Native nations do want to educate the public about who they are, but they want to have control of it. They want to be able to be a part of that education, and they just haven’t ever been at the table until NAGPRA was passed… Also, there’s about 150 tribal museums that are owned by native nations and they are likely better places to go if you want to learn about them.”