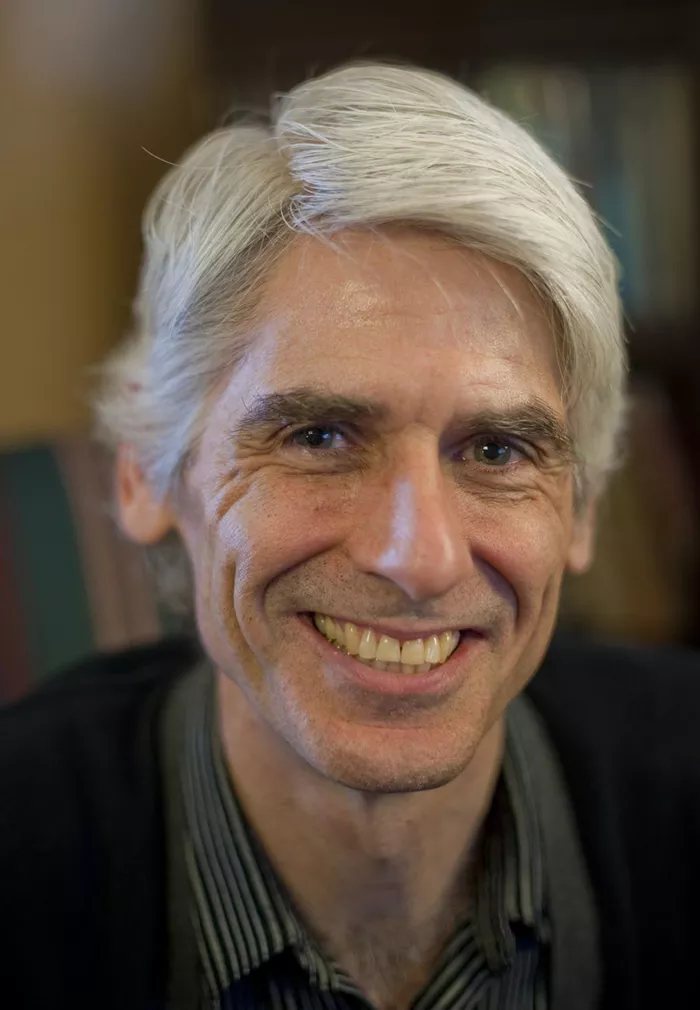

An Interview With Poet Jim Daniels

'I carry the city around inside me no matter where I go.'

Audio By Carbonatix

[

{

"name": "GPT - Leaderboard - Inline - Content",

"component": "35519556",

"insertPoint": "5th",

"startingPoint": "3",

"requiredCountToDisplay": "3",

"maxInsertions": 100,

"adList": [

{

"adPreset": "LeaderboardInline"

}

]

}

]

Jim Daniels’ first collection, Places/Everyone appeared in 1985. I was 19. I came upon this book by chance killing time at a used bookstore in Ann Arbor. Up until that moment, I thought I knew what a poem was, what a poem could be about. The poems in Places/Everyone were unlike the poems I’d been told to read. They didn’t feel like poem poems. They didn’t sound like poem poems. These were poems about the everyday, about the commonplace, poems, in short, that made me want to write poems and poems about the places and the “everyone” I thought I knew. These kinds of poems are the best. They invite us in to the daily conversation, giving us permission to speak about what it means to be a part of this world. And Jim Daniels has practiced that art in the 13 poetry books that have since followed, including his most recent collection, Birth Marks (BOA Editions, Ltd.).

Metro Times: This new book opens with these lines: “I am not a minister’s son or a former pro boxer, but I have a few things to say.” What is it in the world, what is it about the world, that keeps Jim Daniels saying?

Jim Daniels: I guess I’m situating myself between the sacred and the profane, and I’m arguing for the ordinary in poetry — for the most part, that’s been my world in terms of my writing. I want to say, there’s poetry in these lives — the ones you and I know, the families that grew up in the Detroit area. No gimmicks, no pyrotechnics — just the hard work of decent, flawed people trying to stay alive.

MT: In that same poem you also write, “There’s no predicting when you’ll find a tiny shell in a pile of gravel.” I can’t help but to think of that image as a metaphor for your poetry.

Daniels: Yeah, it is a kind of ars poetica poem, I think, that’s why I opened with it. You don’t always find that shell, but if you stop searching, then what’s the point? One of the jobs of a writer I think is to find the extraordinary in the ordinary. Sometimes the shell looks a lot like a piece of gravel. Sometimes what looks like a shell is just a piece of gravel. The shell: It’s something hard that contains — or at one time contained — something alive. You’ve got to stop and look hard at this small thing.

MT: You also write, in a poem that recalls going to a Black Sabbath show at the Michigan State Fairgrounds, “Poetry was all I had that wasn’t toxic.” Can you talk a bit about the “toxic” and how poetry was a sort of antidote?

Daniels: Yeah, the toxic. The drinking age was 18 in Michigan back then, which meant, back in my neighborhood in Warren, and in a lot of other places, that the “trickle down” drinking age was around 14. I started drinking, and drinking heavily, way before I should have — I didn’t know what the hell I was doing. Drugs were in the mix too, but at that time, drinking was really the problem. I was getting wasted a lot, and that really became the focus of my life to such an extent that I quit drinking right around high school graduation, when a lot of people were just getting started. I started again and amped up the drugs big-time, then quit again, started again, then quit for good, but my whole freshman year of college I was straight and sober. It was like college was my dry-out camp for me to try and get my life together and get rid of all the poison. I don’t want to go into a catalogue of all my little sins and crimes, but in general, my behavior itself was toxic. Cruel. Destructive. Selfish. It kept me from myself, if that makes any sense — it pushed me further from looking inward, where I needed to look. It was poetry that allowed me to turn inside and have a good look and rediscover my heart.

MT: Phil Levine writes, “We burn this city every day.” You write, “It’s never stopped burning.” There’s a question somewhere in between these two voices — if you can hear it being asked.

Daniels: Well, I will say a couple of things. First, Phil is great. I have a photo above my desk that Phil had my wife take a number of years ago at the Dodge Festival. He said he wanted a photo of two Detroit poets. Later, he mailed the photo to me. It was a great gesture from a great poet. One of my highlights was reading with him at Alvin’s in Detroit. A shout-out to the legendary M.L. Liebler for putting that together.

I would never try to speak for Phil, but what I was trying to get at was that long after the riots, the literal burning — and the Devil’s Night fires — that the city continued to smolder — economically, spiritually, in so many ways. That in some ways, the city’s never recovered from the ’67 riots. But also, fire as a positive force — I doubt readers would get all this, but I was also thinking about fire as a life force, that it can reflect the spirit of a people and place — defiance, the will to survive, the fire burning inside.

MT: I consider you a Detroit poet. You write, “In ‘68, when the wind blew in off the river, Detroit still reeked wet smoke from the riots.” Your poems reek of Detroit. You grew up in Warren. You live in Pittsburgh now. You’ve been living there for more than 30 years. And yet your poems are still very Detroit. In what ways do you see yourself as still being a Detroit poet?

Daniels: That’s a great question. Detroit, we can all agree, is a complicated place. I never think of myself as any kind of authority on Detroit — particularly since I haven’t lived there in so many years. I come back regularly to visit family, but it’s not the same thing. Phil Levine has his version of Detroit. I have my version. And all I can do is tell my stories as part of the larger complex story of the city.

Sometimes I ask myself, “What is it about Detroit? Why are you still writing about it so much?” That’s why I titled the new book Birth Marks, because where I was born, where I come from, literally and figuratively, has marked me and the way I view the world forever. And I think that’s how I see myself as still being a Detroit poet — I carry the city around inside me no matter where I go.

To address the other issue, I was born on the east side of Detroit, and when I was just a toddler, my parents moved to our house in Warren between Eight and Nine Mile off of Ryan, behind Bronco Lanes bowling alley, where they stayed for around 50 years. So, yeah, Warren is my place — and anyone reading this knows Warren is not Detroit by any stretch of the imagination. Nor is it Birmingham by any stretch of the imagination. … Actually, one of the things I often write about is the border mentality of growing up near Eight Mile. Long before Eminem, long before Coleman Young told the criminals to “hit Eight Mile,” Eight Mile was a symbol. My next book of short stories is called Eight Mile High — Michigan State University Press will publish it next fall — so I’m really zooming in on that territory. Of course, there’s no Eight Mile High, but that fictitious school is a kind of constant through the book. I write about other places — Pittsburgh had got a hold on me too — but Detroit, to paraphrase the writer Richard Price, is the “ZIP code of my heart.”

As part of the Scratch the Page series presented by the InsideOut Literary Arts Project, Jim Daniels reads from his new book of poems at 7 p.m. on Wednesday, Feb. 12, at the Museum of Contemporary Art of Detroit, 4454 Woodward Ave., Detroit.