Intimate and personal in a manner belying its scale, James Cameron’s work on Titanic holds up as well as ever, making its new 25th anniversary re-release an opportunity well worth prioritizing. Fully self-aware as a work of high melodrama, the film opens with a disarming sort of confessional frame. Cameron deploys Bill Paxton (potent as ever) as his maximally earnest stand-in, playing a research scientist investigating the ship’s wreckage for reasons of obsession as much as enterprise (specifically, chasing after the Heart of the Ocean), reflecting nakedly upon his own fixations and aspirations without disregarding his own craft’s financial side. (For evidence of this enduring fixation, just try the documentary Cameron released six years after: Ghosts of the Abyss, in which he explores the wreckage of the Titanic firsthand.) A form of quasi-direct address opening the film, the film’s frame narrative plays from the outset with a kind of promise: an assurance that he’ll speak, even through fiction, plain and from the heart.

But amid the decaying ruins of the ruptured vessel, there’s an air of stale haunting without a bite accompanying the perception, making the long, historically distanced dead little more than a statistic: the ship but a rotting antique inviting historical projections. In restoring the vessel in a lavish feat of historical re-enactment, then, there’s more at stake for Cameron than rewinding the clock; the film’s not just a matter of adding life and flesh to old bones, as a certain strain of mannered docufiction might so often be.

Structuring the film as much as history or romance (surely some part of the rationale in an anniversary re-release circa Valentine’s Day) is a biting critique of class I’d remembered but only so well. Beneath its more gentle, blunt, and sometimes limited verbal satire of upper-class pretensions (Cameron, dialogically speaking, isn’t quite Jane Austen) lies a fiercer attention to inequity, and the deep lies and structures that render people unequal to one another. While quite a white movie racially speaking (one imagines it might be less so now), the film’s lack there leaves it with a sense of unfettered authority, confidence, and focus that comes with a full and firsthand knowledge of its terrain (Cameron having been, by this point, both very rich and very poor.) While lacking in considerations we’d call intersectional now, Titanic takes aim squarely at divisions erected along class lines, presenting them as a web of linked fictions dividing passengers and crew alike from one another.

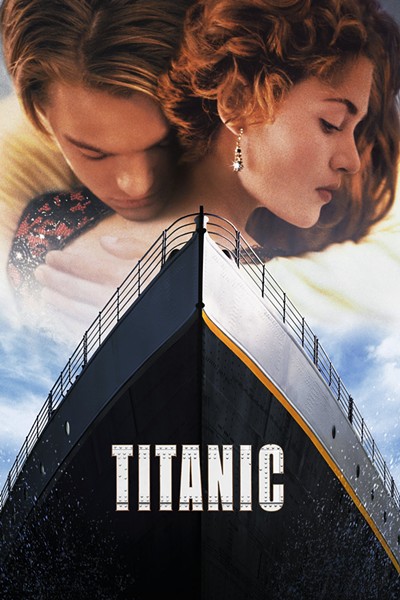

This is plainer nowhere, of course, than in the film’s central romance — which mourns the instrumentalization of marriage and courtship in the interest of money and presentation, both at the steep expense of chemistry and love. With Kate Winslet as Rose DeWitt Bukater battling for her freedom against the prim forces of her confining mother (a fine, credible Frances Fisher) and an oppressive brute of a fiancé (ever-sneering Billy Zane), the introduction of Leo DiCaprio as a boyish rapscallion, Jack, makes it clear she has quite a bit to lose. But these familiar, tangled dynamics make up but one constellation in a broader sea of stars that paints class as all-encompassing, routinely a matter of life and death.

From the bright glow of Rose’s dress amid the haze of the engine room to the many scenes of the film’s key pair darting from floor to deck to floor, what freedom exists is found in this: a transgression of the ship’s (and thus society’s) demarcated lines of class. Able to partake in a tony meal one moment and dance drunk in a storeroom the next, it’s not just youth that liberates the film’s leads but a disregard for our class society’s cruel, divisive nonsense.

It’s easy to take a film like this for granted, to experience it as a set of clichés even as it helped set them up (though Cameron’s extraordinary bullishness, taken alongside his confidence and sense of grandeur make him a hard man to copy well). In rewatching, moments which might have been dulled by remembrance after some six or seven years felt startlingly sharp; so much of what the film accomplishes (as with Cameron’s latest Avatar film) seems near-impossible to pull off. The scene where Jack supports Rose climbing up the ship’s bow is enlivened by their physical chemistry and the way they seem to clutch at one another; their verbal banter over his portfolio of drawings is likewise buoyed by the way that, even in what’s unlikely to be an early take, Rose seems so genuinely disarmed. Key to this — somehow, I think — is the fact DiCaprio’s performance is so eagerly striving, verging on the ungainly. (There’s something disorienting, too, about the way he, even at 21 when they started two years of shooting, looks a bit too young for the role.) In this sense of wily resourcefulness, Cameron finds another avatar (lowercase this time), a figure armed with the bold, brash luck of a decent gambler — able to bluff or elbow his way to a win.

But Cameron, a refined and solid stylist — a visionary, even — doesn’t need to bluff. Sure of what he’s doing as he must be of who he is, he’s an artist fully in control, often in ways that seem mysterious. What Rose’s present-day narration, delivered from the standpoint of her life as an elderly widow visiting the research vessel, gives the film remains — outside of certain flickers near the film’s start and finish — hard for me to make a claim about, save for the fact it provides some freedom in Titanic’s structure. But barring its naked presence as a kind of “device,” albeit one enriched by Gloria Stuart’s warm and careful performance, I’m inclined to think that Cameron would have found some other workaround to take the movie anywhere he wanted. Laying out the ship with studied precision only to lay waste to the whole thing later, he’s a director whose sense of control seems often to be in almost perverse opposition to any sense of traditional refinement.

Even with Cameron being at once an earnest populist and a surefire egomaniac, it’s hard to believe now — when most works are given over either to self-seriousness or to the limpest strains of glib irony — that anyone could make a movie this vast and eccentric, and still so deftly balanced in the time we live in now. There’s Cameron’s singularity as a director, sure, that makes this kind of thing so rare. But then there’s the forceful whims, too, of the industry’s idle rich — who block most films worth making. If the film’s class allegory were just a little truer, they’d be stuck waiting for — as the elder Rose describes quite late — an absolution that will never come. Given how few fictions lend this and so many other kinds of comfort, we’d best cherish the ones we’ve got.

Film Details

Coming soon: Metro Times Daily newsletter. We’ll send you a handful of interesting Detroit stories every morning. Subscribe now to not miss a thing.

Follow us: Google News | NewsBreak | Reddit | Instagram | Facebook | Twitter