Leaving his Upper Peninsula house on Nov. 9, 1986, a cold Sunday night, Frederick Freeman drove down to metro Detroit through Wisconsin, Illinois and Indiana. He needed to limit his time on Michigan's roadways. He was a wanted man in this state.

Stopping at roadside pay phones, he checked in frequently with his pregnant girlfriend, Michelle Woodworth, back at the couple's rented house in Rock, about 20 miles north of Escanaba. He called from restaurants, gas stations and rest stops for any news.

The only information Freeman had came from a lawyer in Escanaba and was wrong. The attorney, a friend's father, told Freeman he was wanted for murder in his hometown of Flint. Freeman thought the victim was a childhood friend who had recently left Escanaba after he and Freeman had a falling out.

Freeman also called Flint police to ask them what he could do to help prove his innocence. After all, he'd been in the Upper Peninsula for several weeks and couldn't have killed anyone downstate, he says.

Flint police finally told him to stop calling. They didn't have him on record as a suspect for anything and didn't have a murder victim with the name he was giving.

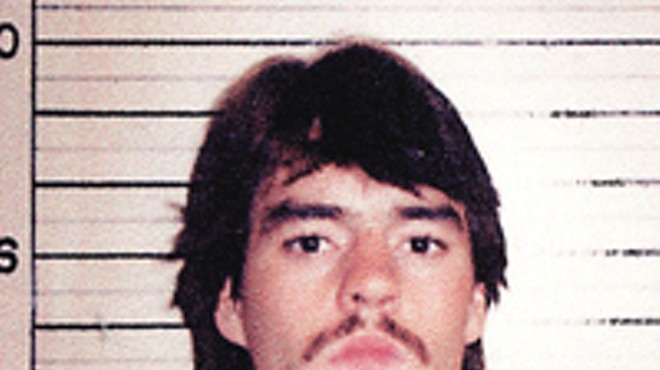

Freeman reached a female friend's house in suburban Detroit after two days of driving his red Mercury Marquis, happy to have avoided cops. At 23 years of age, he was no stranger to the law. He had a conviction for bad checks in Washington state and an assault charge pending in suburban Detroit after a tussle with his ex-wife's boyfriend. He also had a pending perjury charge in Ann Arbor for using a friend's driver's license. He'd been living under two aliases to avoid arrest. He'd been getting by up North by selling vitamins.

When he called Woodworth on Thursday, Nov. 13, she told him Port Huron police were at their home with a warrant. He was a murder suspect. She was scared. Freeman asked to talk to one of the officers.

It wasn't his childhood friend who was dead, a detective named John Bowns told Freeman, it was Scott Macklem who'd been gunned down. Macklem, 20, was the son of the mayor of Croswell, a small town northwest of Port Huron, and was engaged to a woman named Crystal Merrill who was expecting his child.

Freeman had lived recently in the Port Huron area, and had a relationship with Merrill for a few weeks the previous spring; they met when he rented some videos from the Port Huron store where she was a clerk. Freeman knew Merrill had previously dated Macklem, but he hadn't spoken to her since July, and he'd moved north around Labor Day. He says he didn't know of the couple's renewed relationship, pregnancy and pending marriage.

Still, Merrill was Freeman's only connection to the case, and he needed to know why police thought he'd killed Macklem. So Freeman called her that night from the pay phone in the back hallway of a Troy coffee shop. She was at her parent's farm in Croswell.

"I wish to god that phone call was recorded," Freeman told Metro Times last month during an interview at the Saginaw Correctional Facility where he is serving a life sentence for the first-degree murder of Macklem. He's changed his name to Temujin Kensu to reflect his Buddhist faith. "I said, 'What the hell is going on?' ... I was trying to find out why they thought I did this."

The two talked for hours with a Sanilac County deputy listening in on a second phone in the house. Merrill's and Macklem's parents were there as well as other officers.

The call began with Freeman offering condolences. "I'm sorry about Scott, I did not bear any malice for him," he told Merrill.

Freeman has always contended he was in the Upper Peninsula the morning Macklem was gunned down in the St. Clair County Community College parking lot and he told Merrill as much during the telephone call.

"I didn't do this," he says he told Merrill. He reminded her he didn't own a gun. He talked about several witnesses in Escanaba who would help prove he was there.

The officer listening in, Sanilac County Sgt. Dave Hall, later recalled Freeman discussing "several different reasons why he may not have been involved."

During the call, Merrill informed Freeman she had told police about his martial arts training. He had taken classes in tae kwon do, karate and kung fu beginning in grade school.

"I had a bunch of martial arts weapons, and she told her mom that I belong to some kind of mafia group or something," Freeman told police following the phone call. "She blew the whole thing out of proportion and made it sound like I'm some kind of Japanese ninja mafia guy or something. I never threatened Scott. I never said a word about this guy."

Freeman told Merrill that police were after the wrong guy. "The police should look at somebody that Scott had made mad." Hall later remembered Freeman saying detectives should be looking for people who, "made [Macklem] mad or aggravated him. That's who I [should] be looking at."

The conversation wandered between Macklem's death, what Merrill had told police, the reasons why Freeman couldn't have killed him and martial arts. At one point, talk was winding down, but police told her to keep Freeman on the line.

Merrill says she cried, took time to go to the bathroom and talked about things that interested Freeman to keep him on the line while police traced the call and sent officers out for the arrest.

Freeman's continued assertion of innocence is not his only argument that he was wrongfully convicted of first-degree murder in St. Clair County Circuit Court in May 1987. And he's attracted a team of volunteer advocates who've been digging into the case, some of them for 15 years. They've found that crucial evidence and testimony either were not considered, not believed or not known to the jury of seven women and five men that convicted Freeman. The jurors also overlooked inconsistencies in testimony and evidence, ignored a lack of evidence in some cases, didn't hear from some key witnesses, including Freeman and Woodworth, and didn't know about other possible misconduct and conflicts of interest of police and attorneys involved in the trial.

These are some of the key elements of Freeman's belated defense:

• No physical evidence would ever link Freeman to the crime. Prints on a shotgun shell box found at the scene didn't match his. One shell turned in to police weeks later had no prints and was a different gauge than the one that killed Macklem. Freeman's clothing didn't have gunshot residue. The shotgun used to kill Macklem was never found nor was Freeman ever proven — or even reasonably suspected — to have owned a shotgun.

• Freeman had an alibi corroborated by several people. Two witnesses confirmed he was in Escanaba having car trouble between midnight and 1:30 a.m. the day of the shooting. Freeman's girlfriend, Woodworth, told police they were at home in Rock the morning of the murder and slept until at least 9 a.m. before heading into Escanaba. Two witnesses confirmed Freeman was in Escanaba by noon and four more testified he was there during the afternoon. Woodworth did not testify at trial, saying she was afraid. Police had threatened her, she reported a few months before the trial, saying she could lose custody of her infant child by Freeman if she testified.

• The prosecution presented a wild theory to counter the alibi witnesses. St. Clair County Prosecutor Robert Cleland, now a judge in U.S. District Court in Detroit, told the jury it would have been possible for Freeman to charter a private plane to fly between Port Huron and Escanaba. He introduced no pilot, no receipt of Freeman paying for the flight, no flight plan or other record of the journey, nor did he provide an explanation of how Freeman, who had little money, could have paid for the flight.

• The single eyewitness to put Freeman at the shooting scene identified him under a questionable police lineup procedure. That witness, who had seen a man driving from near the murder site, recognized two of the six people in the lineup as police officers. Another woman who saw a man driving away could not identify Freeman as that man. A witness who saw a "suspicious" man in the parking lot an hour before the shooting picked a different man out of the lineup although he had earlier picked Freeman out of a series of mug shots.

• A jailhouse snitch lied about Freeman confessing and then received help from the St. Clair County prosecutor's office. A few weeks before his trial, Freeman shared a jail cell for a few hours in Port Huron with Philip Joplin, a career criminal. Joplin testified at Freeman's trial that Freeman confessed to killing Macklem. Joplin would later recant in a letter and on videotape, saying he had lied to get a better deal on his sentence. Another man who was in the cell at the time testified that Joplin, who died in 1998, was lying about Freeman's confession. "[Freeman] was saying that he didn't do it," Booker Brown, the other prisoner, said at Freeman's trial. Documents show Freeman's trial judge and a St. Clair County assistant prosecutor assisted Joplin with a preferred placement in the Department of Corrections. In front of the jury Joplin denied getting any deal.

• The star witness was Crystal Merrill, who'd dated Freeman briefly before getting back together with Macklem. Merrill spent the first two days of trial on the stand, testifying that Freeman raped her on their first date but that she continued to see him for several weeks, never telling anyone about the alleged assault. She described his cache of ninja weaponry and a way he said he could make door keys from clay. She said Freeman was a "higher up" at a secret organization that fought prostitution and drugs where he could "call contracts out on anybody." She said he had listening devices and could hear conversations across parking lots and camped out in cornfields around her family farm to learn what kind of tractors they owned. "He told me he could read my mind," she said. Most of her testimony would go unsubstantiated by other witnesses.

• Freeman's defense attorney and the lead investigator had a history that presented a conflict of interest. David Dean, Freeman's attorney, had previously represented the lead detective, John Bowns, after he was fired from the Port Huron police department. Court records show that, in 1981, a special agent for the Michigan State Police was conducting an investigation at the Midway Inn, a Port Huron motel where sports betting, bookmaking and high stakes poker games were suspected. The State Police investigator reported that Bowns was there but the officer made no arrests and reported no suspected violations of gambling or liquor laws. In 1982, Bowns was fired for conduct unbecoming a police officer and neglect of duty. Dean would represent him in a legal battle for unemployment benefits, which they lost. Bowns was reinstated with Port Huron police about a year before the Macklem murder.

• Dean was a cocaine user, and drug abuse led to problems in the courtroom for him. He pleaded no contest in a bust, a year before Macklem's murder, for using coke in an Ohio park. In 1990, he was forced to withdraw as the court-appointed lawyer for a murder defendant who testified he had sold drugs to Dean. In 1991, one of Dean's clients earned a new trial for a 1989 murder; a judge ruled that Dean's substance abuse had affected his status as defense counsel in that case. During those proceedings, Dean's assistant testified that Dean was using drugs at the time of Freeman's case. In 1993, the Michigan Attorney Grievance Commission Board suspended Dean from practicing law and ordered substance abuse counseling. According to newspaper reports, board investigators charged that Dean had purchased cocaine or had it purchased for him at least 19 times during the summer of 1990. In 2001, the Michigan Attorney Discipline Board denied Dean's reinstatement petition. Dean, who now lives in Florida, recently told Metro Times he hasn't used in a decade and was not using at all during the Freeman trial.

• Freeman's team has identified another man as the shooter. A man Freeman met in prison says he knows who shot Macklem. The motive, he says: a dispute over cocaine dealing. Freeman's investigators and lawyers have confirmed new information from this source and can place the new suspect in the same circles as Macklem and in the Port Huron area about the time of the murder. As far as they know, police never questioned him.

But that 1986 evening, as Freeman spoke to Merrill, the cops had locked in on Freeman as their only suspect, court records and newspaper accounts show. Merrill, who was working at Macklem's father's insurance office in Croswell at the time of the shooting, had told police she suspected Freeman as the shooter at the hospital just hours after Macklem died.

Investigators never had another suspect, they eventually admitted during trial. They pursued their case against a single person of interest. Nothing from Macklem's background was investigated.

Since then, Freeman's volunteer advocates — former FBI agents and Michigan State Police investigators, attorneys, private investigators, a documentary filmmaker and a veteran television journalist, Bill Proctor from WXYZ-TV (Channel 7) — have uncovered what they say is evidence of widespread corruption in the Port Huron and St. Clair County criminal justice systems at the time of Macklem's killing and that ties Macklem's death to his involvement in cocaine dealing.

Having exhausted his state appeals, Freeman this year filed a habeas corpus motion in U.S. District Court in Detroit that will force a judge there to determine if the conviction and imprisonment violate Freeman's constitutional rights. His team is hopeful about the petition's chances, which is before Judge Denise Page Hood.

"There wasn't the evidence to convict him. It just wasn't there," says Hank Glaspie, a 24-year FBI special agent who has worked pro bono for Freeman's release. "There's a lot more information behind what appeared at trial. ... It's some scary shit."

Glaspie and the team have identified a new suspect as the alleged shooter, and he is a man who is free and living in metro Detroit. These volunteer investigators have detailed inconsistencies in the police investigation and prosecutors' arguments and documented new or different testimony of key witnesses that would have helped Freeman's case. Some of it they won't talk about on the record.

Former Michigan Supreme Court Chief Justice Thomas Brennan read the 13-day trial transcript this year after learning of the case from a student at Cooley Law School in Lansing. "Reading the trial transcript as an outsider, you just had this smell of the whole thing," he says. "I don't see how they could convict the guy. ... Had I been the trial judge, I hope I would have had the guts to throw the case out."

But the Michigan criminal justice system has taken no real second look at Freeman's case. And Freeman is left wondering what happened to his right to a fair trial and if he will ever be freed.

The Crime

Twenty-year-old Scott Macklem was living with his parents and routinely drove his 1973 Plymouth Turismo along two-lane country roads to reach St. Clair County Community College. The Macklem family was well-known in Croswell, a farming community with about 2,000 residents then. Scott Macklem's father, Gary Macklem, had been mayor since 1982, and the Macklem family name appears in local newspapers as far back as 1878.

During the fall semester in 1986, Scott Macklem was a general business student and worked as a stock clerk at a men's clothing store in Port Huron. In 1984, the year he graduated from Croswell-Lexington High School, other students voted him "most popular" and "best dressed." He'd been captain of the basketball and golf teams. But that fall 1986 semester, his algebra teacher would testify at trial, Macklem's attendance had been irregular.

The morning he was killed he was scheduled for an 8 a.m. gym class, but he didn't attend. Instead, at about 8:55 a.m., he was at the side of his car in a campus parking lot when a shot rang out. Other students heard it, possibly echoing off buildings.

A shotgun blast tore through Macklem, ripping a one-inch hole in the left side of his jacket, traveling through his back rib cage and continuing upward through his lungs. It penetrated both lungs, grazed his heart, damaged his spleen and liver and fractured two ribs. Medical staff at Port Huron Hospital, where he was pronounced dead, would remove a filler wad from the shell of a 12-gauge or larger shotgun and seven pieces of buckshot, according to a Michigan State Police lab report. An autopsy later that day showed he had died of "internal injuries and hemorrhage due to gunshot wound." He would be buried in the Croswell cemetery where 25 other Macklems rest today.

Forensic tests on Macklem's red jacket, lavender sweater and striped shirt would indicate the shotgun had been fired from about 6 feet away. His car keys were found in the driver's door, his gym bag on the ground. He was on his left side with an arm outstretched when a student attempted CPR before emergency medical workers arrived. The student described to police a "deep gurgle sound coming from down deep within the victim" as he did mouth-to-mouth resuscitation, according to reports.

Several witnesses heard the shots but their descriptions of people and cars in the area would conflict. Some matched Freeman, others didn't.

Wanda Crowe, a 45-year-old student, noticed a woman in a red sweater walk "right by" Macklem's car about the time the shot went off. Because the woman "made no effort to help Macklem," it stuck in Crowe's mind that whatever was happening was some kind of hoax. Crowe also told police she saw someone sitting in a bright yellow car directly across from hers. "She turned in a plate number and we don't know if it was run or not," according to police notes at the time. The report submitted the day of the murder by lead investigator Bowns makes no mention of the car or the plate.

Another woman, Jean Anter, approached Det. Harry Hudson at the scene when police arrived after the shooting. A full-time student during the day, she worked at the St. Clair Inn as a waitress with a 5 to 11 p.m. shift. When she got out of her car that morning, she noticed a tan or brown medium-sized vehicle driven by a white male through the parking lot at what she thought was a "faster than normal rate of speed," Anter said.

As she walked, she saw Macklem walking by his vehicle but crouched over. "Help me, help me. I'm hurt," she heard him say. She continued toward class but noticed a blond-haired woman getting into a car parked on the opposite side of the curb from Macklem's car.

Of the four students police interviewed in the parking lot shortly after the shooting, three reported seeing a white man driving a car that was either medium-sized or small and tan, brown or reddish brown in color. Two of the four said they saw a woman near where Macklem was found, possibly driving away.

In the weeks and months after the murder, police would eventually talk to additional witnesses or reinterview the original witnesses about the parking lot scene. Five mentioned seeing a woman and four mentioned seeing a man either near Macklem or driving a car away from the lot. The witnesses gave descriptions of cars in the lot just after the shots that included seven colors: yellow, blue, tan or brown, gold, black and reddish brown.

Port Huron Police Officer James Carmody was one of several officers dispatched to the scene who talked to students there. He met Kathleen Ballard and Rene Gobeyn, who shared a morning philosophy class. Ballard, who worked an afternoon shift at a Wendy's restaurant, parked about 60 feet away from Macklem's car that morning. As she walked through the parking lot, she heard what she thought was a firecracker. When she got closer to Macklem's body, she saw a "small" vehicle pulling out of the parking spot next to his car.

From what she saw, the driver was attempting to conceal his face, but she could tell it was a white male, maybe 19 years old, with dark hair. She told police the car was a Horizon or Chevette and reddish brown in color but she didn't see the plate. After Freeman was arrested and placed in a lineup, Ballard would be "unable to select anyone," according to a police report.

Her classmate, Gobeyn, eventually would be crucial to the prosecution's case but his first statement to police was similar to other students' that morning. In his initial interview with Carmody, according to the report, Gobeyn said the man driving the car was white and about 25 years old.

Gobeyn said the man appeared to be wearing an olive-green army jacket and a dark blue ski mask that was folded up over his forehead and may have had red trim around the mouth. "No further information on the physical of the driver," the report noted.

Gobeyn described the car to Carmody as being "a small, possibly foreign make vehicle. A pinkish-tan or dark tan in color," according to the report. "His first impression was that it may have been a Mazda," Carmody recorded.

Because he had heard gunfire and then saw the car coming from the direction of the shot, Gobeyn told police he made a mental note of the license plate of the car. He wrote it on a folder when he reached his classroom. When interviewed, he gave it to officers.

But a computer check failed to find a license plate matching Gobeyn's information.

According to Carmody's testimony at Freeman's preliminary examination three weeks later, Gobeyn had mentioned a beard on the driver. There was no record of that detail the day of the shooting.

At about 11:50 a.m., Carmody went to Port Huron Hospital to turn over information to Bowns, who was "in charge of the case," according to Carmody's initial report. The Macklem family was at the hospital where they were "notified of the incident."

Bowns got the blood-soaked shotgun shell wad from the doctor and eventually tagged it and put it in the Port Huron Police Department's property room to dry. He spoke to Merrill, Macklem's pregnant fiancee, who had known Macklem since kindergarten.

"She stated that she went out with the suspect in this matter," Bowns wrote. Crystal Merrill described her ex-boyfriend as "real heavy into ninja" and "always talking about going to kill someone or hurt someone. She stated at one time he beat her up just to see what her reaction would be, and to see how she could defend herself," according to Bowns' report. Merrill said she feared the man she named as his alias John LaMar and that he was "capable of doing anything." She described him as "strong" and "muscular" and having "no fear of anybody."

Later Merrill would call Freeman possessive and say he had wanted to marry her. She said he could read her mind and that he kept his chest tattoos puffed up "with some kind of quills." She would describe Freeman a few weeks later as a man who was enough in love with her to murder another man.

While Merrill talked to Bowns the first time at the hospital, her 16-year-old sister, Tracy, approached Carmody and said she knew the suspect whom her sister had dated. The Merrill sisters felt LaMar was responsible for the shooting, they told police.

Based on the teens' statements, Port Huron police had a suspect and they referred to him that way in police reports and to the media from then until trial.

Tracy Merrill had been to LaMar's house, she told Carmody. She didn't know the address but she could take the officer there. As they drove to it, Tracy Merrill told Carmody about her sister and LaMar. They had dated about six months earlier, and Tracy thought LaMar was a little unusual. Her parents did not like Crystal going out with him. Tracy went to find her sister at LaMar's house one night because she wasn't at the family's farm to milk the cows in the morning.

The teen told Carmody that another of Crystal's boyfriends, someone named Arnell, "had been beat up by this John LaMar." Later records show that Arnell Hope told police he "had never knowingly met this LaMar." Hope did not testify at trial.

After finding the house with Tracy, Carmody dropped the teen back at the hospital and called the owner of the property, Karen Shieman. On the phone, Shieman told Carmody about the tenant she also knew as John LaMar who had rented the house on April 17. She knew him as he had described himself when he arranged to rent from her: an engineer who did computer work over the phone and was a minister's son and law-abiding religious person. She rented him the house and would come to know Shelly LaMar who came from Flint and moved in with LaMar the next weekend.

Neighbors started telling Shieman her tenant was a little odd by their estimations, she told Carmody. He practiced karate in the yard. He used karate-style weapons. He had two or three cars around, including a small red sports car. They heard John and Shelly fight and suspected he beat her, Shieman told Carmody.

Around Labor Day, the couple moved out. While going through "junk" they left behind, Shieman found papers she believed identified LaMar as Frederick Freeman. She kept them and now she told police about them and other related incidents.

On Nov. 2, a man had contacted Shieman saying he was the father of the woman she knew as Shelly LaMar. The young woman was actually Michelle Woodworth, he said, and John LaMar's real name was Frederick Thomas Freeman and he was wanted in Washington for parole violations.

Carmody included this in his report that afternoon.

Within about 20 minutes of calling Shieman, Carmody found an investigator at the Olympia Police Department in Washington and asked about Freeman. He was told of Freeman's bad check charge and suspected assaults and breaking-and-entering incidents on the West Coast.

Carmody found the two felony warrants in Michigan for Freeman. One was for perjury in Ann Arbor, the other was for aggravated assault in Pleasant Ridge. A caution was attached: The subject might use martial arts weapons.

Captured

By the end of the week, Port Huron police had located Freeman in the Upper Peninsula. According to records obtained recently by Metro Times from the Delta County Sheriff Department, Port Huron police contacted officers there two days after the shooting and told them a suspect in a Port Huron homicide may be in their area. Records from Escanaba Public Safety show Bowns contacted officers there as well. A supplementary report from Escanaba police stated Freeman was an "expert in martial arts" and that he and two other people were evicted from an Escanaba house on Oct. 8.

Surveillance began. According to court records, police in the Upper Peninsula had Freeman's landlord identify him from photos, presumably mug shots from his arrests in Washington and Pleasant Ridge. Posing as deer hunters looking for a place to hunt, state troopers and a sheriff's deputy visited Freeman's residence in Rock on Nov. 10. Woodworth told them her "husband" would be back later, according to reports.

On Nov. 12 Port Huron police got a warrant for Freeman that notes the complainant was "Sgt. Bowns on info/belief." On Nov. 13, a Delta County judge issued a search warrant for Freeman's person.

That was the night Freeman called Merrill from the Troy coffee shop after talking to Bowns who was at the house in Rock.

Freeman clearly remembers his last moment of freedom. He leaned back from the phone to ask a server for another cup of coffee. He realized other customers and employees had left the shop. Then, Troy officers, alerted by Port Huron police, approached Freeman. They were backed by a SWAT team. "They walked up and said, 'We don't know what's going on,'" Freeman says.

They handcuffed and searched Freeman, saying, "We got a report that you've got a lot of weaponry." Police found nothing. The police report from the time notes, "Officers were advised to use extreme caution as suspect is a martial arts expert and may be armed with poison darts." Merrill had told Port Huron police Freeman was a ninja who carried poison darts in the tongue of his shoes.

Transported to Port Huron the next day, Freeman found himself the only suspect in the murder of a man he insists he didn't know. As he freely talked to any police officer or attorney he could, he told them how he'd been 450 miles away from the scene of Macklem's death. He'd have people testify to that. He didn't know the victim. He'd dated Merrill earlier that year, but he hadn't seen or spoken to her in months since he, not she, ended the relationship. The day of the murder, he'd been in the Upper Peninsula, trying to get his broken-down car to run, going to a martial arts school and hanging out with friends.

In a taped interview conducted as officers drove him Nov. 14 from Troy to Port Huron, Freeman made the same claims he would for the next 20 years.

"What makes me mad is I know where I was. I can prove where I was so I know they've got nothing against me except that Crystal said I did it. Crystal told them that I'm some underground guy," Freeman said. "I never threatened Scott. I never said a word about this guy."

Later that afternoon — the beginning of Freeman's two decades behind bars — Port Huron Police got a report from the Michigan State Police. An anonymous caller reported seeing the suspect in the Macklem shooting driving a red Ford Escort on Interstate 94 between Port Huron and Mount Clemens that afternoon. The caller told police he knew of Freeman and learned he was a suspect from newspaper reports.

It couldn't have been Freeman, he was in custody.

A man who closely resembled Freeman was out there, driving a red Ford Escort, which was one of the car models described leaving the scene of the shooting.

Nearly 20 years later, another source would claim to give Freeman's team of investigators the name of Macklem's killer.

The red Ford Escort described in the November 1986 police report would link to him.

Next week: In Part 2 of this story, Frederick Freeman's long shot for freedom and the unlikely team of advocates trying to see justice in this case.

Research assistance was provided by Metro Times interns Achile Bianchi, Caitlin Cowan, Jonathan Eppley and Alfred Ishak.

Sandra Svoboda is a Metro Times staff writer. Contact her at 313-202-8015 or [email protected]