The dynamics at play in the new pop art exhibition at the Detroit Institute of Arts are perhaps best exemplified by a work from Sister Mary Corita, a lesser-known Los Angeles artist who also happened to be a nun at a Catholic school. In "Enriched Bread," Corita appropriates the bold colors and patterns of Wonder Bread packaging, added a quote from philosopher Albert Camus, and gave the piece a name that nods to the Catholic eucharist.

"Great ideas, it has been said, come into the world as gently as doves," the Camus quote reads, in part. "Perhaps then, if we listen attentively, we shall hear amid the uproar of empires and nations, a faint flutter of wings, the gentle stirring of life and hope."

"She has this fabulous quote in there, which is telling artists to engage with the world," says Clare Rogan, the museum's curator of prints and drawings. "You have somebody who you would think wouldn't be very engaged with the world — you know, a nun — who is actually incredibly engaged with contemporary pop art and its latest possibilities, and with existentialist philosophy, and with advertisements."

The image was made in 1965, and the DIA acquired it in 1966 — which shows how the museum was on top of the Pop Art movement, when the fine art world was reacting to the rise of mass media. Rogan, who joined the museum in late 2017, says she was inspired by the museum's collection for her first exhibition in her new role.

"When you come to a collection, one of the great joys is finding out what the strengths are," she says. "I started looking through the whole collection of prints and drawings, and quickly realized that this was an area where not only did we have great material, but we had a history of collecting from the very early 1960s and had a chance to bring out some pieces that haven't been on exhibition in 20 years." Since many of the works are on paper, they can only be on display for short periods of time so as not to get damaged by light. The show marks an opportunity for visitors to see many of these works together for the first time in a generation.

Rogan says she chose the period of 1960 to 1975 for the show because it was the apex of the movement. "I think the thing with Pop is it's a really interesting transition, especially in the history of printmaking, because it's a moment when artists are engaging with the everyday world — with the modern, the new," she says. "We have to remember advertising as we know it today was just new and exciting in 1960. This was very much a youth revolution as well as an art revolution." It was also a marked move away from the work of the older generation of Abstract Expressionists, whose art was more about the internal vision of the artist.

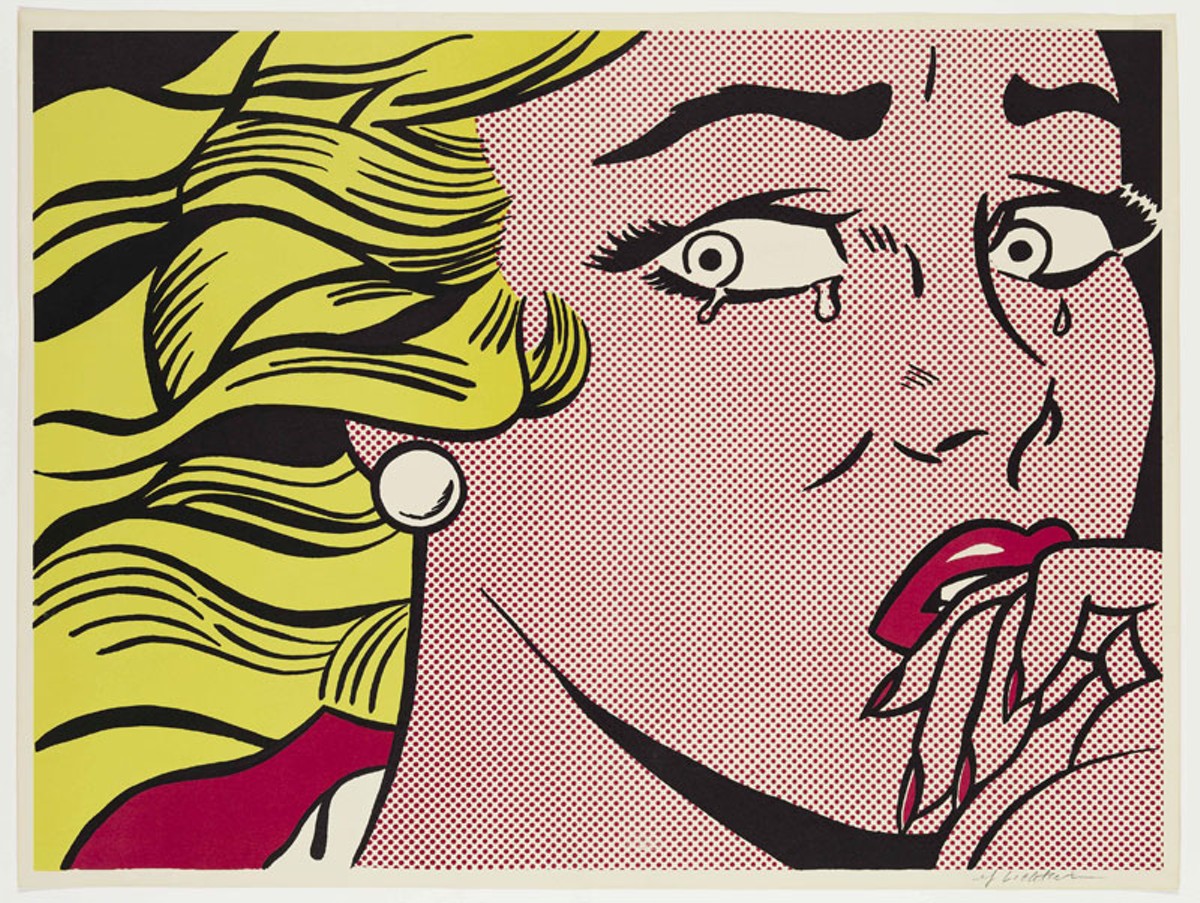

By then, artists were looking to pop culture for inspiration, whether it was Claes Oldenburg's ode to Good Humor ice cream bars or Roy Lichtenstein taking comic book panels and enlarging them, forcing the viewer to see them in a new perspective. "That's part of a lot of the energy and the vibrancy of pop art, is that embrace of contemporary life," says Rogan. "This idea of appropriation — the idea of taking something and making it larger, stranger, highlighting it, critiquing it, turning it around, making it be seen in a different way."

At the time, a crop of fine art print shops had emerged, which could help artists mass produce their works. Some, like L.A.'s Gemini G.E.L., experimented with new techniques to create editions of three-dimensional works out of plastic, as they did with Oldenburg.

It also turned the idea of what is considered "fine art" on its head. Lichtenstein's "Crying Girl," for example, was printed as a poster to advertise a show at New York's Leo Castelli Gallery. "If you went to see the show you'd get one," Rogan says. "And there are all these stories about people who collected them and put thumbtacks in them and stuck them up in their bedrooms and never thought about it. And now it's in a museum collection."

By grouping the work chronologically, Rogan is able to tell the story of the context the work was created in. In this case, that was the turbulent 1960s and '70s, as Space Age optimism made way for political upheaval — hence the show's name, From Camelot to Kent State.

"A lot of the work in the earlier part of the decade is really embracing the modern and the new, with a very positive, very celebratory embrace of mass culture," Rogan says. That all changed by Richard Hamilton's 1970 print series "Kent State," which features a grisly image of a college Vietnam War protester shot at the hands of the National Guard. Hamilton sat in front of the TV with a camera on a tripod for a week in search of a subject for a print edition when the image flashed on the BBC.

"It seemed right, too, that art could help to keep the shame in our minds," Hamilton said at the time. "[The] wide distribution of a large edition print might be the strongest indictment I could make." The image, then, is also exemplary of Pop Art — taking the ephemeral and immortalizing it. The show runs through Aug. 25.

From Camelot to Kent State: Pop Art, 1960–1975 opens on Sunday, Feb. 17 at the Detroit Institute of Arts; 5200 Woodward Ave., Detroit; 313-833-7900; dia.org; Free with museum admission, which is free for Wayne, Oakland, and Macomb county residents.

Get our top picks for the best events in Detroit every Thursday morning. Sign up for our events newsletter.