In Terence Davies’s Benediction, poetry’s treated as alive a medium as any. That’s as it should be, for the biographical film, which tracks the real-life English wartime poet Siegfried Sassoon, accounts for the weight and passage of time and the enduring vitality of artistic expression without caving to nostalgia. Written by Davies himself — who, at 76, is known as well now for his Emily Dickinson-centered A Quiet Passion as for his luminous autobiographical works — the film splits the difference between history and diary with an air of elegant decision. Regarding its historical subject from a perspective that feels miraculously firsthand, Benediction exudes a sense of presence through its subjective portraits of community, country, and Sassoon himself, culminating in a shared picture that feels both bright and damning.

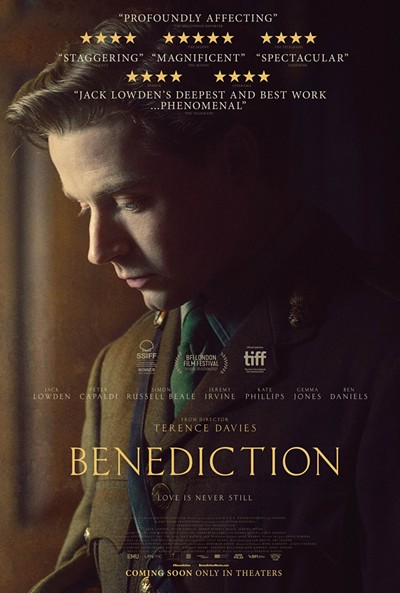

Benediction’s sense of immediacy can be attributed not just to Davies’s skill as an artist but to its intimate proximity to his own life. Raised Catholic in the 1940s, Davies knew he was gay from a young age: a concrete reality he worked for years to escape. For Sassoon (played with earnest, nearly stern force by Jack Lowden as a young man — then as an old one by Peter Capaldi), this reality was one he wrestled with as well in ways shaped strongly by his own environment. In Sassoon’s case, though, identity provided a window into a certain world, allowing access to experiences he was allowed to feel with more than a sense of embattlement or affliction.

Gay identity is never presented as Sassoon’s only source of perspective or of voice onscreen — and it’s not nearly enough to explain his artistic work or the person that he was. Between Lowden’s performance and Davies’ direction, Sassoon’s antiwar convictions are granted plausible sources rather than definite ones. Drafted into the Army in World War I alongside his brother, who died there, Sassoon gained notoriety by publishing a scathing objection to the conflict in 1917, before its end: an action that saw him shipped off to a psychiatric hospital rather than discharged from service.

From this point, portals begin to open. While nominally in confinement, Sassoon meets both a sympathetic doctor and a fellow patient (the poet Wilfred Owen, played by Matthew Tennyson), who edits an arts journal at the clinic. Through a web of sly euphemisms — Benediction’s humor is one of its best features throughout — these men recognize one another as gay, carving out a small, sheltered space of fairly open expression. This bubble of relative safety, introduced within the hospital, becomes a steady stream of new, quite youthful experience after Sassoon’s release. Through a winding circuit of upper-class parties in the years after the war, Sassoon moves through a succession of well-connected lovers while riding a current of national fame until, eventually, this lustrous world ebbs. Portending a future and family life we encounter in Capaldi’s sparse but purposefully deployed scenes, Benediction spans time and ruminates on aging with a sense of constant presence, treating memory as just one section in the broader palette of emotional experience; to the film’s credit, retrospective experience is never tinged in any single fashion.

Much of the interplay between these sections — capturing Sassoon’s experiences of youth and aging — casts them with a greater weight than they’d have alone, while never feeling melodramatic. The film presents wartime experience solely through archival techniques (a similar effect was used for the Civil War in A Quiet Passion), a distancing effect that renders it ineffable; by contrast, the physical and psychic wounds sustained within it are given space to quietly and more visibly fester.

These psychic burdens are rarely addressed or “treated” with an end in mind — but their effects are ambiently felt, constantly expressed. The most striking emotional discharges are found in Davies’s renderings of a small, privileged gay artistic communityof composers, theatrical entertainers, and poets like and unlike Sassoon — parties not above rivalry with one another and of varying degrees of artistic accomplishment. Within this space, both friendship and romance are prone to a kind of tonal whiplash, with the film’s intellectuals frequently deploying their considerable powers against one another in bouts of vicious verbal fencing. Presenting Davies’ remarkable wit as both a unifying expression of a scene and — humbly — a kind of surface entertainment, much of Benediction’s power lies in the way its experiences accrue a new meaning when strung together. The sharp, sometimes superficial prettiness of Sassoon’s peacetime world curdles and seems to sour well before it more visibly rots from age and time.

For his own part, Lowden’s Sassoon participates in this opulent environment while seeming largely un-seduced by it. While willing and able to defend himself in arguments and appearing often at parties to the delight of his artistic admirers, his presence both at public events and within a more private gay milieu is made to feel ephemeral — until it doesn’t. When he does speak out, stepping outside the role of chronicler or observer, he does so as his own artistic self; with a classicist’s authority and an activist’s conviction, his lines are delivered from a decisive posture that lends gravity to both his utterances and silences.

Davies’s film sidesteps the kind of boosterism common in queer screen depictions. Both sympathetic and critical, it allows Sassoon to be as severe (if still embattled) critic of both preening and philandering partners as he was of military leadership in the film’s first act: a man who seems to be caught always on the fringes of cultures, scenes, and times. The difference, of course, is that these intra-community conflicts are intimate and cultural whereas Sassoon’s wartime activism was public and political, and thus easier to vent on or step away from. In Davies’s depiction, the film’s close-knit community proves susceptible, thanks to a blend of insularity and competitive ambition, to petty gossip and cruel squabbles — stemming from a more sympathetically rendered sense of co-dependency and need.

Davies cuts to the quick of not only Sassoon’s but a much broader array of experience, allowing longing, reflection, and change wrought by time to be chief subjects. Arranging its shuffled catalog of experience with a skillful writerly and editorial hand, Benediction’s winding procession finds a sense of authenticity in pursuit not of plotlines or universal themes but of personalized and resonant experiential and emotional truth. That’s the job, too, of quite a bit of poetry — and it works as well here as it’s likely to anywhere else.

Benediction opens locally for at least a week at Phoenix Theatres Laurel Park Place on June 2; if we're lucky, it will receive a longer and more expanded run.

Film Details

Stay connected with Detroit Metro Times. Subscribe to our newsletters, and follow us on Google News, Apple News, Twitter, Facebook, Instagram, Reddit, or TikTok.