For information on Frannie Shepherd-Bates' other theatrical project, the Magenta Giraffe Theatre Company, see magentagiraffe.org.

Frannie Shepherd-Bates sits in a hard plastic chair in the front row of what looks like a small school auditorium. Concrete walls painted an institutional white surround the DIY theater veteran, while a dozen orange-clad inmates sit attentively nearby. Shepherd-Bates exudes an air of serene confidence, an attitude that many folks might find hard to maintain at Michigan's only maximum-security prison for women. On top of that intimidating prospect, she's currently leading the group through a particularly difficult passage in Shakespeare's ubiquitous masterpiece, Hamlet.

Sure, everyone thinks they know the tragic end to the Bard's melancholy prince, but how many non-English majors have read it line-by-line? The fall of Shakespeare's protagonist through a deep existential crisis may take place in a medieval Danish court, but his words touch hidden nerves in the prisoners of the Huron Valley Correctional Facility.

Huron Valley is home to a little fewer than 900 women, whose convictions range from simple drug possession to first-degree murder. It's hardly a surprise that most of the inmates come from backgrounds plagued by poverty, abuse and other obstacles to education. These women have had to learn the skills to survive in heart-wrenching circumstances, and they're tougher than most before they even enter Huron Valley. Some inmates admit they've only been able to cope with these new, confined surroundings by developing thick emotional boundaries. It's necessary for the world that exists inside these walls.

In the auditorium, a young brunet inmate we'll call "D" (strict prison rules allow inmates to only be identified to outsiders by a first initial) shakily reads through Hamlet's soliloquy on life's questionable meaning and the enticing alternative of death. It's difficult territory for D, who looks no older than 22. She stands alone on stage, and, with a voice barely above a whisper, she stops to sound out words she's never encountered before. When D finishes, Shepherd-Bates congratulates her on getting through the unnerving task, and then asks D if she understood what she just read. With a small shrug, D replies, "Not really," and sits down with obvious embarrassment.

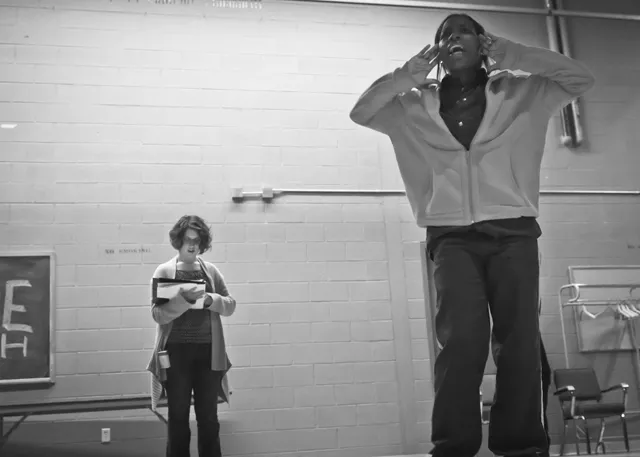

Here's where Shepherd-Bates shines as a teacher. With compassion and authority, she breaks the Bard's formidable prose down until it truly feels relevant, and most importantly, inspires a deep empathy for the character. D listens carefully, and then ascends the stage for another try. This time she reads in a loud and confident voice,

Whether 'tis nobler in the mind to suffer

The slings and arrows of outrageous fortune,

Or to take arms against a sea of troubles,

And, by opposing, end them?

She finishes to a round of applause from her fellow inmates. Suddenly D starts to cry. "I think about wanting to die all the time," she says and walks quietly back to her seat in the chilly auditorium.

That was the last time D came to class. Shepherd-Bates remembers that D "... came to the conclusion that the piece was about Hamlet wanting to kill himself and being too afraid to do it. She gave an incredible reading, then never came back. I think the piece hit her so hard ... those are very deep, difficult emotions to deal with. Not everyone's up to it."

This is the emotional connection that Shepherd-Bates wants all the women in her class to feel. To her, Shakespeare's themes of love, betrayal and revenge are still capable of resonating with a modern audience, and she's on a mission to change the lives of Michigan's female prisoners with his work.

Bringing America's often-forgotten prison population into contact with Shakespeare began in the mid-'90s at the Luther Luckett Correctional Facility in LaGrange, Ky. Theater director Curt Tofteland created the program, nationally known as "Shakespeare Behind Bars." The program inspired an award-winning documentary of the same name, and began a Shakespeare revolution at prisons across the country.

Inmates who have been involved in the program say they experience a profound personal growth through it, first by recognizing the depths of their own emotions, then by connecting with fellow prisoners through the camaraderie of sharing a stage. Those benefits are hard to quantify, but they have a big effect on a number that isn't.

Participants in the Shakespeare Behind Bars program have drastically lowered recidivism rates to a low of 7 percent, according to the Shakespeare Behind Bars website. Compare that to a 2004 Pew Center study putting the national recidivism rate at 43 percent. Then consider an estimate by the nonpartisan think-tank Center for Michigan that the state spends more than $32,817 per inmate, per year. It's easy to see why prison officials are opening the doors to theater teachers like Shepherd-Bates. Across the nation, there are currently five official offshoots of Tofteland's program, including one at the Brooks Correctional Facility in Muskegon. Numerous programs inspired by the original Shakespeare Behind Bars formula have taken root nationally, however, including the one at Huron Valley. Shepherd-Bates says she was personally guided by Tofteland during the creation of her program, called Shakespeare in Prison to differentiate it from others across the country.

Although it will take a few years to measure any success in decreasing recidivism at Huron Valley, the women involved are vocal about the ways they've been affected by their experience.

On a recent Tuesday morning, five female inmates rehearse a scene from Othello, when Desdemona, Othello's beautiful but luckless wife, attempts to defend herself against charges of adultery.

Acting the parts of both the abuser and the battered spouse in a violent relationship isn't far from reality for many female inmates, says L, who plays Desdemona. She says that, by learning to embody the character, she's been able to release some of the anger and pain of "... being in relationships with abusive men, where they run you down, make you hurt."

An older woman with a blond crew-cut says she's most drawn to Shakespeare's humorous side. Inmates, she explains, are not allowed to touch one another, "so there's few opportunities to laugh or play around. I can forget that I'm in prison when I'm on stage."

And that chance to momentarily forget labels like "inmate" or "prisoner" could be the greatest benefit from programs like Shakespeare in Prison, because all of society benefits when each of us is allowed to reclaim our humanity.

Amanda le Claire is a freelance writer and video producer. Send comments to her via [email protected].