Audio By Carbonatix

[

{

"name": "GPT - Leaderboard - Inline - Content",

"component": "35519556",

"insertPoint": "5th",

"startingPoint": "3",

"requiredCountToDisplay": "3",

"maxInsertions": 100,

"adList": [

{

"adPreset": "LeaderboardInline"

}

]

}

]

Detroit Police Department Facebook

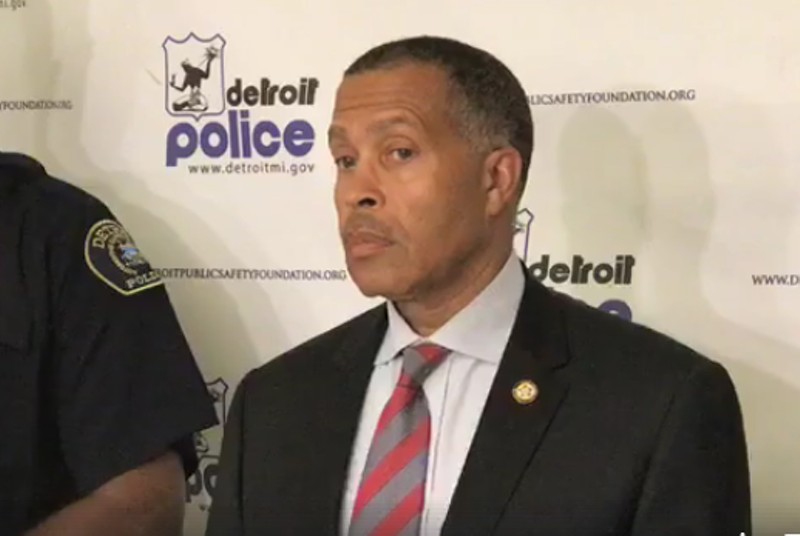

Detroit Police Chief James Craig.

We can understand that public officials want to put their best foot forward, but even our jaundiced eyebrows raised a bit during a Thursday news conference intended to tout what the Detroit Police Department says was a banner year for crime reduction.

According to the department’s self-reported data, crime fell across the board in 2017 when compared with the year before, with almost all crime categories showing their second straight year of reductions. Overall violent crime dropped 7 percent from 2016 and overall property crimes, like burglaries and larcenies, fell 9 percent. Cast as most significant, however, was the reported decline in the city’s homicide rate, a 12 percent year-over reduction to 267 killings — a low not seen in half a century.

“Certainly when I look at what it was like coming in the door in 2013, the morale was a big issue, [there was] a lack of trust, high crime, but today we’ve seen a major progression in overall decline in violent crime, and not by accident,” said Police Chief James Craig. “I’d like to emphasize not by accident.”

Surrounded by more than a dozen law enforcement officials from the city, county, state, and federal levels, Craig attributed the crime reductions to strategic partnerships with the various agencies present. The U.S. Attorney’s Office, for example, has significantly cracked down on gang violence in Detroit over the past two years as part of a multi-agency program called Ceasefire, indicting more than 100 alleged members from some of the city’s most notorious crews.

But when the chief and Mayor Mike Duggan, who was also on hand, turned their focus from strategy to staffing, claiming that the improvements had something to do with a more robust police force, we had to pinch ourselves to remember where we were. Wasn’t a similarly themed “things are improving” press conference also delivered at this time last year — the same year that the FBI went on to name Detroit the country’s most violent big city? Hadn’t the DPD hemorrhaged officers between 2000-2015, at a rate that far outpaced the city's population decline? Aren’t department-reported homicide numbers known to serve as an unreliable barometer for the amount of bloodshed in the city? And what of that cooperation with other agencies — wasn’t 2017 the year we saw an inter-agency brawl when some Detroit patrol officers thought a group of undercovers from a neighboring precinct were selling drugs?

We felt a fact-check was in order.

Detroit Police Department Facebook

Detroit Police Chief James Craig holds a news conference on the department's crime statistics for 2017.

“We couldn’t do this without the hiring of additional officers,” Craig said before going on to champion the department for hiring a whopping 662 officers over the past two years.

What he failed to mention was that, during the same period, the department lost 444 officers due to attrition. Further, the DPD didn’t exactly hire 662 new cops, so much as it brought on 512 while shuffling things around internally to put 171 who were working desk jobs onto the streets, according to a spokesman for Mayor Duggan.

But a net gain of what the Duggan administration says is 239 officers over two years has hardly recouped the losses the department endured before and during bankruptcy. According to a 2015 Detroit News story headlined, “Fewest cops are patrolling Detroit streets since 1920s,” there were just 1,590 officers with the department by the middle of that year — a reduction of 37 percent over the previous three years. Today, that number has climbed to only 1,621, according to the city’s latest data. There are an additional 59 neighborhood police officers who function as community liaisons.

“The situation has not improved the way we’d like,” Detroit Police Officers Association president Mark Diaz said in an email last week. “The guys are still working double shifts because of manpower shortages. More often than not they are forced to work doubles because of officers calling in sick due to issues related to exhaustion.”

According to Diaz, a combination of these conditions and bankruptcy-era cuts to benefits has made it diffucult for the department to hold onto officers — particularly seasoned ones. While starting pay has increased for new officers, from about $27,000 a year during the bankruptcy to $36,000 today, Diaz says pay levels still max out below those of the police departments of neighboring cities and Detroit’s benefits aren’t as good. The elimination of longevity bonuses for long-time officers, for example, has sent more experienced patrolmen and women in search of better work. As a result, Diaz says that of the department’s approximately 1,621 officers, 700 of them have less than five years on the job.

“The mayor can proudly display what he’s done with hiring, but it’s a facade,” Diaz said in an email following the Thursday news conference. “The city is being protected by fewer and fewer seasoned officers every month.”

He added, “We are in a very dangerous situation.”

Numbers game

“Stats don’t lie,” Craig remarked at one point Thursday, as if knowing the improved crime data might illicit some head-scratching amid virtually unchanged staffing levels.

And while stats may not lie, they can certainly be manipulated, as evidenced by the aforementioned decision to portray the department as adding hundreds of officers per year.

In the case of DPD’s crime statistics, the department may be able to cloak a possible increase in crime through a discrepancy in the way it tabulates crimes across categories. For example, the total number of crimes in the categories of homicides, non-fatal shootings, and carjackings are based on the number of people victimized by each of those crimes. By contrast, the numbers for the remaining categories — which include violent crimes like robberies, aggravated assaults, and rapes — are based on incidents. That means that if, for example, three people are assaulted by one assailant on one occasion, that could count as one crime.

According to an investigative report published in October by Pulitzer Prize-winning journalist Charlie LeDuff, this discrepancy made it possible for Detroit to tell citizens it had reduced violent crime in 2016, while the data it submitted to the FBI, which counts crime based on total victims, showed an increase. According to LeDuff, when factoring in population declines, the FBI numbers show Detroit's crime rate has actually stayed much the same in recent years. At best, he says, there has been only a 1 percent reduction in crime per capita since Craig assumed the role of police chief in 2013.

Homicide stats paint incomplete picture

The Detroit Police Department’s homicide numbers are known to provide an incomplete picture of killings in the city, with the omission of homicides deemed “justified” standard practice. That means that if Joe pulled a knife on John and John shot and killed him, the slaying does not count toward the city’s homicide rate.

But the department has in the past also been found to incorrectly categorize some killings as justified in an apparent effort to cast itself in a better light. In 2008, for example, Detroit police incorrectly classified at least 22 of their 368 killings that year as “justifiable” and did not report them as homicides to the FBI as required, according to a separate report by LeDuff.

As recently as 2012, even Wayne County Prosecutor Kym Worthy expressed skepticism over the department’s homicide data.

“I know they don’t report with accuracy,” Worthy said in a story by MLive. “It’s self-reporting. All the things they call justifiable may not be justifiable, is what I’m trying to tell you.”

“As a general proposition, I believe that a lot of cities under-report (criminal homicides) because they don’t want to be seen as the most violent.”

This year there were 15 such “justifiable” killings, according to a Detroit police spokeswoman — the same number as last year. Worthy’s office will release its own 2017 homicide stats for Detroit in two or more weeks, a spokeswoman with her office says. The Wayne County Medical Examiner will also release a homicide total later this winter.