Audio By Carbonatix

[

{

"name": "GPT - Leaderboard - Inline - Content",

"component": "35519556",

"insertPoint": "5th",

"startingPoint": "3",

"requiredCountToDisplay": "3",

"maxInsertions": 100,

"adList": [

{

"adPreset": "LeaderboardInline"

}

]

}

]

Most of Tracie McMillan's book is devoted to her undercover work in America's industrial food system. But this excerpt comes from her time in Detroit, where she spent several months meeting people involved with the city's urban agriculture, and chronicling its history. Though these city gardens may not be Detroit's savior, they offer an inspiring example, and alternative to the corruptible food system, providing health, produce and bringing communities together.

This passage opens with McMillan living in southwest Detroit.

In the balm of springtime evenings, I'd watch my neighbors work in the community garden, crouching low to yank out weeds or ambling up the sidewalk behind a creaking wheelbarrow in the long shadows of twilight. Our garden wasn't that big, maybe half a lot, but there were hundreds of them throughout the city in backyards, vacant lots and parks, most of them growing food not in the city soil but in raised beds atop it — a bid at doing an end-run around any industrial contamination that gets past a standard soil test. Since the early 2000s, Detroit's limited supermarkets and an overabundance of vacant land have inspired city residents to start growing their own food, in gardens ranging from tiny corner lots with collards and tomatoes to a four-acre expanse complete with a mushroom patch. They've churned out such an abundance of greens, herbs and tomatoes that the most prodigious among them have formed a cooperative, Grown in Detroit, to sell their excess at farmers' markets and restaurants around town. In all, Grown in Detroit grossed around $60,000 in produce sales in 2010. One neighborhood gardener, Greg Willerer, was so enthralled by urban farming's potential that he founded a farm in 2010, using his own yard before expanding to a couple vacant lots to grow an array of herbs and salad greens. He started selling to restaurants, got himself a stand at Eastern Market, and in 2011 he launched a community-supported agriculture project catering to city residents. In exchange for greens and vegetables all summer long, locals pay Willerer in a number of ways: in full in March, piecemeal through the season, or even by donating labor. Across town, on the city's east side, Carolyn Leadley and Jacob Vandyke founded Rising Pheasant Farms in 2009, selling produce wholesale through Grown in Detroit. In 2011, they expanded and paid for a retail stand at Eastern Market, where they sell sprouts next to Willerer on Saturdays.

In the Detroit of 2010, even people whose primary concerns were profit and jobs had begun to think pairing the city's vacant land with large-scale agriculture could make sense. In 2009, a local financier, John Hantz, announced plans to establish a 50-acre pilot project to establish large-scale commercial farming in the city, arguing that it would gobble up vacant, blighted land while generating profits. A local drug-treatment organization has begun drafting ambitious plans for Recovery Park, an agriculture, housing, and community development project designed to employ recovering addicts and other residents in living-wage jobs growing and processing food. And Majora Carter, a renowned urban advocate for green space, announced plans to recruit the city's urban farmers for a new produce label, American City Farms, conceiving of the effort primarily as one of economic development and job creation.

All of these larger players will be capitalizing on Detroit's long history of urban agriculture, which has been a part of the city's fabric for more than a century. In the 1890s, poor Detroiters were encouraged to grow food on 430 acres of vacant land by the mayor, Hazen S. Pingree. Precursors to the Victory Gardens of World War I, these early plots were dubbed Pingree Potato Patches, and by their third year, the value of food grown in the patches outstripped the cash aid distributed to the city's poor. Backyard gardening has always been strong in Detroit, a city where 79 percent of all homes are single-family, but local urban agriculture got a boost in the 1970s from a federal program that set aside money to encourage food production in urban settings. A brainchild of a liberal New York City congressman, Fred Richmond, the Urban Gardening Program gained the support of conservative Southern representatives in 1976, when Richmond made them a pitch they couldn't refuse: Help people in cities grow food and they'll start to appreciate how hard it is to grow it — and they'll be more open to the issues that matter to agricultural states. In 1977, the program launched in six cities, including Detroit.

The program revived a link between the nation's agricultural extension offices, the public venue for America's agricultural policies, and urban soil. During World War II, extension offices had helped to set up Victory Gardens in cities, but after their demise, extension's agricultural efforts became strictly rural affairs. A joint program between the country's land-grant universities and the USDA, extension offices can offer advice to anyone who wants to grow food. At the biggest universities, extension offices run massive research and resource programs; the extension at University of California-Davis, for example, helped develop the tomato harvester machine. Extension, as it's called colloquially, is where America's public agriculture gets made and shaped. Typically, it supports and expands on the conventional methods already in practice, further refining the industrial agriculture that has fueled America's food supply for generations. Techniques outside that purview do sometimes trickle up into extension's repertoire, but only when people push for them. That's how sustainable agriculture got a toehold in a handful of offices in the 1970s, a move that amounted to minor but official acceptance of the practice. Even so, extension offices have rarely led the pack on new ways of farming, focusing instead on refining existing ones and responding to farmers' current needs — which are, of course, defined by the way they already farm.

Truthfully, it's left to the outlying innovators — the organic pioneers, the urban farmers — to come up with a meaningful agricultural practice outside the industrial model. Big, industrial growers have to persuade extension services to help them, too — but they're often the ones funding research, which gives researchers a strong incentive to meet big growers' needs. (Most big agribusiness companies have their own research departments as well.) Accordingly, extension has had little incentive to suggest radical changes like leaving behind pesticides, adopting new labor practices, or making smallscale growing profitable. For seventeen years, the Urban Gardening Program, small as it was, bucked that trend and put money toward figuring out how to use city land to grow food instead of flowers and shrubs.

In 1994, the Urban Gardening Program ended, a victim of a funding reorganization that made it an optional part of another agency, instead of having its own specified place in the budget. Some cities continued to promote urban agriculture for food production, rather than beautification; in New York City, the local cooperative extension figured out how to keep its urban agriculture agent, John Ameroso. Now retired, Ameroso proved to be a relentless advocate for food production over recreation in garden spaces, pointing out that gazebos, after all, take away growing space. In the federal program's final year, the gardens grew $16 million-worth of food, the last year official records were kept. It was considered a nice, but ineffective, effort; all well and good, but not worth its own place in a budget. Productive agriculture was big; you could never make money doing it any other way.

I first meet Malik Yakini on a warm morning in May, at D-Town Farm, two acres tucked within a massive city park on the city's northwest side. (By 2011, they had expanded to four acres.) Yakini, the founder and principal of an Afrocentric charter school, founded D-Town Farm in 2007 as chair of the Detroit Black Community Food Security Network. The idea was to provide access to fresh, healthy food grown without chemicals while putting vacant land to good use, as well as to encourage the city's black community to "do for self" by providing jobs and income. Giving people the means to feed themselves, went the thinking, was one way to help mitigate the city's sometimes sparse options for fresh food. At first D-Town was more an idea than a place, with Yakini and fellow activists farming one plot of land one year, a different one the next. In 2008, after two years of negotiations with city officials, Yakini and his colleagues managed to strike a deal for two acres tucked into a park on the city's northwest side.

The day I visit is perfect spring: blue skies, breeze rustling through glossy poplar leaves, sun pouring down. Yakini meets me at the farm's gate, near a little wooden signpost with a placard explaining the city's food access problems — and the hope that D-Town's fields can provide a partial solution to them. Other signs dot the property, stopping points for the volunteer tour guides who take visitors like me around. He gestures at the tall wire fence encircling the growing area, adjusting the knit cap keeping his dreadlocks in place as he looks up at it. "We had a pretty severe problem last year with inventory shrinkage," he says wryly, explaining that both humans and wildlife helped themselves. We pad around on tilled earth inside, his shell-top Adidas sinking into furrowed ground between adolescent greens. When a half-dozen urban gardeners from New York show up, in town for a conference, I tag along on their tour of the mushroom patch and beehives, where our guide, Aba, informs us that they are "raising some strong Detroit bees that'll make it through the winter."

Much of what has kept urban agriculture from generating money has been its small scale; it's hard to make up the cost of growing food, which requires daily work no matter how little you grow, if you're harvesting just two tomato plants. Commercial production requires balancing larger-scale production (which means more food to sell) against the cost of the inputs required to grow it (compost or fertilizer, tractors or pitchforks). The conventional wisdom about selling food just the way it comes out of the ground is that to do so profitably requires either massive, Walmartian scale or very high prices. Trimming back the vast network between farm and plate — the marketing system — is one way to get around that equation; that's why growers like Willerer, who sell directly to the customers eating their produce, can charge affordable prices. Another way to boost profits is by making food more appealing to customers — or, to use food-business lingo, to add value to it. "Once you wash something, cut it, put it in a bag, it gains a lot of value," says Yakini.

Currently, very little of the produce grown in Detroit has much done to it at all. For the Grown in Detroit label, produce has to follow basic industry standards; you don't wash raspberries, because the delicate fruits will disintegrate, but you do wash lettuce — a step that in turn requires facilities in which to do the washing. Then it's taken to market as quickly as possible, because the only cooling facilities available tend to be people's home refrigerators. "Growing produce is our thing, we've gotten fairly good at that," says Yakini. "But you have to be able to move it, move it quickly, and clean and pack it, and that side is kind of underdeveloped. We need to work much more on the infrastructure."

That's already on the agenda for the Grown in Detroit farmers, who have begun remediating a few acres of soil a few blocks over from Eastern Market, planning to use the space as a training facility, producing food for market. They also plan to build a packing house and cooling shed, and with that infrastructure in place, they expect to harvest and prepare even more food for sale. At the same time, they'll be operating as something of a de facto extension office, expanding on established agricultural practices for urban areas and developing new ones; testing different varieties of crops that suit the city's hot, wet summers and can be grown in tight spaces; and using intercropping so that one stretch of land can grow two kinds of food. Although there's little real estate pressure in Detroit, land still costs money, and spreading multiple inputs like water and compost over vast acreage can be tricky.

The question comes up again and again: Could you feed Detroit from farms within its limits? In 2010, researchers at Michigan State University decided to try to answer it, and they found that urban growers might not be able to supply the city with everything it eats — but they could make a significant contribution. Nearly half the nontropical fruit eaten by city residents could be grown here, and three-quarters of their vegetables; a similar study of Cleveland suggested residents could meet all their produce needs by cultivating vacant land and industrial rooftops. In both studies, the most interesting finding of all was how little land these farms would require. Take Detroit, for example. Researchers estimated that if growers practiced conventional industrial agriculture, they'd need 3,600 acres of land to produce that much food — nearly three-fourths of the vacant city-owned land in Detroit. But if they practiced biointensive agriculture — the kind in use at most of the urban farm plots, with compost, intercropping, and diverse crop plans — researchers found they'd need 568 acres, about 12 percent of the city's vacant land. (For comparison, Manhattan's Central Park is 843 acres.) Feeding Detroit most of its fruits and vegetables wouldn't require remaking the city into the endless cornfields of the Heartland, or the massive vegetable monocrops of California's Central Valley. Instead, it'd look more like a giant backyard garden, with lettuces giving way to tomatoes giving way to spinach in the same plot.

Yet urban farming gets pitted against redevelopment constantly — at least in Detroit. In 2011, a successful dog day care in the city's redeveloping Midtown neighborhood ousted a longstanding community garden, buying the city lot on which the garden sat so that it could expand. The two abutted each other on a stretch of Cass Avenue, a one-time thoroughfare now lined with boarded-up storefronts. Officials jumped at the opportunity to turn it into a tax-paying property; the garden was more of a neighborhood effort than a commercial farm plot. "If we all think about where we want Detroit to go . . . we don't want it looking like a farm in Kansas," said Councilmember Ken Cockrel. "We want it looking like Manhattan."

Yet most of the farmers I met in Detroit aren't envisioning Kansan cornfields so much as they're hoping to bring truly good food into their neighborhoods and maybe eke out a living doing it. Over toward City Airport, in one of Detroit's roughest neighborhoods, Mark Covington farms a couple blocks of land down Georgia Street from his house, the same one he grew up in. He moved back home a couple years ago, after losing his job as an environmental technician, cleaning oil tanks and commercial buildings. To keep busy, he started growing food for himself and his neighbors. Covington is something of a local celebrity for his work, but that hasn't made him sanguine about farming's prospects in his hometown. "Urban agriculture won't save Detroit," Covington told me matter-of-factly when I visited. But after seeing the work being done here, it seems possible that the city's farms could go a long way toward meeting the city's demand for fresh produce. They might even begin to help answer the biggest question of all when it comes to everyone's meals: How are we going to grow food for more people with the same amount of land? Either way, it seems a good idea to me.

The American Way of Eating

by Tracie McMillan

Scribner, $25, 338 pp.

Excerpted from The American Way of Eating: Undercover at Walmart, Applebee's, Farm Fields, and the Dinner Table. Copyright © 2012 by Tracie McMillan. Excerpted with permission by Scribner, a Division of Simon & Schuster, Inc.

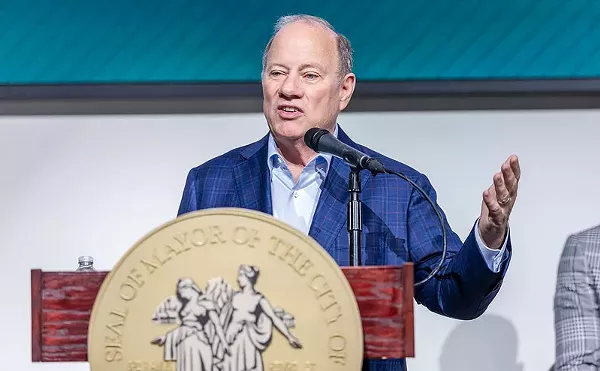

Tracie McMillan will appear noon to 1:30 p.m. Wednesday, April 4, at U-M Dearborn's College of Arts, Science and Letters, 3035 CASL Building, Dearborn; 313-593-5490.

McMillan will also kick off the new Talk Soup series at Colors, a series of conversations with food system and social justice thinkers, dreamers, and doers open to the community and public. The event takes place from 6 to 9 p.m. Thursday, April 5, at 311 E. Grand River Ave., Detroit; 313-496-1212; colors-detroit.com.