When is a good time to talk about gentrification in Detroit?

That was the question a group of local stakeholders mulled over during a panel discussion held Saturday inside the Jam Handy on East Grand Boulevard. The consensus, overwhelmingly, was now. Gentrification is a topic that, especially in the case of Detroit, has prompted heated discussion. That’s not only because downtown Detroit’s rents have increased over the past year, but due to the highly visible instances of displacement occurring in Capitol Park .

And although some have written off worries of gentrification in Detroit as premature, organizers of the discussion hosted by the Michigan Citizen on Saturday (titled “Two Detroits? Gentrification”) felt it’s a discussion the city would benefit from having now rather than later.

While the slackers at the Hits crew surprised ourselves by arriving to the discussion in time for the panel’s early 8 a.m. start, we were immediately heartened by the diversity of the event’s audience. More than 100 attendees crawled out of bed on a beautiful Saturday morning to partake in a lively discussion — blacks, whites, hipsters, young, old, the well-dressed and the dressed-down.

It’s no question the city of Detroit needs to attract investment to boost property values and increase tax revenue in order to stay afloat. That was a point highlighted with surprising candor by former president and CEO of the Detroit Economic Growth Corporation, George Jackson, last year.

“When I look at this city’s tax base, I say bring on more gentrification,” Jackson told a crowd at the Grosse Pointe War Memorial during a forum on Detroit’s future. “I’m sorry, but, I mean, bring it on. We can’t just be a poor city and prosper.”

Well, sure, George, but the idea of creating a thriving city that’s inclusive of all of its residents seems to be a better endgame than generating new investment at all costs. Yes, Detroit needs to grow, but surely there’s a way to accomplish that goal without excluding those who have remained in the city through the thick of its worst days, no?

That was the initial point brought by Catherine Kelly, publisher of the Citizen, who also moderated the panel. Detroit is in the process of crawling out of bankruptcy court, with hopes of capitalizing on the increased development happening in certain Detroit neighborhoods including downtown, Corktown, and the Cass Corr — (oops, Midtown). With that said, it’s important to recognize that Detroit is a “changing city,” Kelly says.

And “the best way to manage gentrification is to plan for it,” she says.

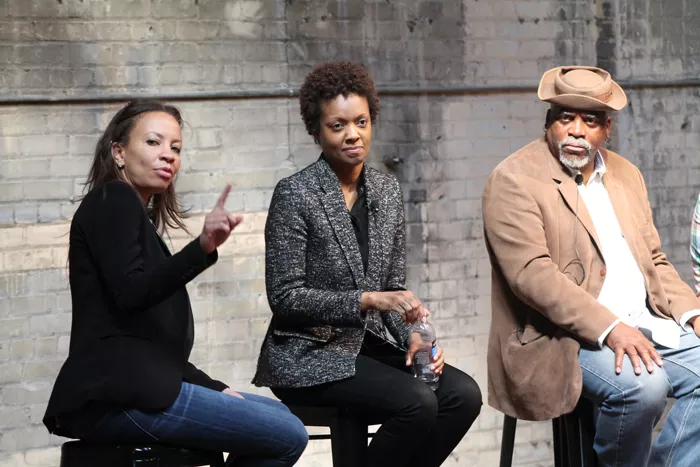

The speakers featured at the panel also included Lauren Hood of Loveland Technologies and Deep Dive Detroit, local hip-hop artist Khary “WAE” Frazier, George N’Namdi of the N’Namdi Center for Contemporary Art, Phil Cooley of Slows Bar-B-Q and Ponyride, and Kirk Mayes, deputy group executive of Jobs and Economies for Detroit under Mayor Mike Duggan.

Hood, a fourth-generation Detroiter, opened the discussion by acknowledging one of the textbook definitions of gentrification — that is, displacement — adding that, although it’s happening in remote cases, “If we don’t pay attention to it, it’d get out of control.”

Cooley, a self-described “cheerleader” of the city when he moved to Detroit 12 years ago, didn’t agree with the assessment, though he acknowledged the potential of gentrification happening in Detroit is real.

A former Chicago resident, the entrepreneur says he witnessed firsthand the negative aspects of gentrification in the Wicker Park neighborhood.

“I hope we do it much better, but I’ll be honest in that we’ll likely make mistakes,” Cooley said.

While there is an undeniably vast amount of vacant properties that need to be filled in Detroit, N’Namdi says there’s no question that gentrification is already occurring, although in a different form: psychological, evidenced by the stress that groups of people experience when a neighborhood changes rapidly.

“I think that psychological part of it is very real, and very scary for me,” he says.

That sort of impact is especially evident in Midtown. The changes occurring over the past couple of years to the neighborhoods surrounding Wayne State University have brought safer streets, new restaurants and additional businesses. As panel attendee Rachel Reed, a resident of the area since 2008, puts it, it’s now become difficult to keep tabs on new establishments.

Reed, 28, says: “I used to make it a point to check out” a new business when it opened. Now some open without registering on her radar. “It’s incredible, the amount of businesses that have popped up since then,” she says.

The dynamic, though — as N’Namdi zeroed in on — was the focal point of a column from Bill McGraw of Deadline Detroit last year on Midtown’s renaissance. McGraw focused on the corner of Woodward and Alexandrine avenues, site of the Great Lakes Coffee Roasting Company’s Detroit location.

“Music played from the house speakers, but some in the youngish and mostly fashionable crowd used ear buds as they worked on their MacBook Pros and read their tablets and iPhones. Beyond the large windows, it was a typical scene as well. Older people on three- and four-wheel mobility scooters negotiate traffic and potholes on a busy Woodward Avenue. A legless man in a motorized wheelchair, his urine bag and catheter hanging on the side, crossed the street. Younger people, huddled against the cold, some wearing worn clothes, walked past. A few ate food from the nearby McDonald’s. A woman carried a red gas can. The different scenes on either side of the glass illustrate a fact of life of the ongoing renaissance in Midtown and downtown Detroit. Neighborhoods are evolving, but they are located in the midst of one of the nation’s most impoverished cities. Gentrification is not new, but as the new Detroit expands, it keeps pushing against an old Detroit that has many residents without the means, or the time, or the inclination, to eat anchovies on toast.”

Although a majority of the panel members describe Detroit as a city ripe with opportunities for its residents, Hood points out that, in some instances, it’s been a less inclusive process than some might admit. It’s essential to educate residents about opportunities, she says.

“If there’s an opportunity there, and you don’t know about it, is there really an opportunity?” she asked.

It’s worth noting that the overall sentiment of the room after the panel concluded its remarks was one of hope. It was a conversation-starter, and the purpose now is to build upon those shared ideas.