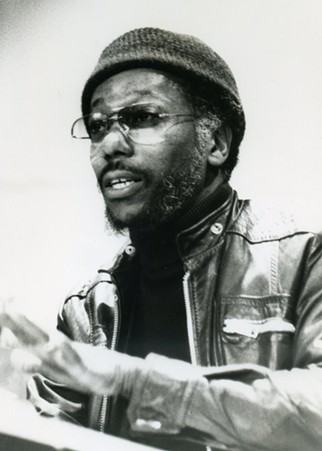

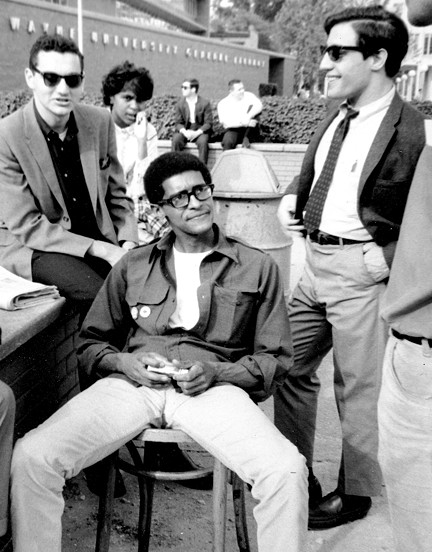

This perspective on the events of the summer of 1967 comes from a few Metro Times fellow travelers in the form of John and Leni Sinclair, and Fifth Estate staffers Harvey Ovshinsky, Peter Werbe, and Frank Joyce. We also sought out John’s old pal Pun Plamondon, as well as author, activist, and longtime MT editorial adviser Herb Boyd, and scholar, journalist, and Hush House co-founder Charles Simmons. Additionally, we talked with Reggie Carter to represent the teenage black radical contingent of the day. Between all of these folks, we hoped to gain some insights into what political radicals and the “hippie counterculture” — a phrase many of them privately grimace at — have to say about that time.

In our interviews, we heard the words “rebellion,” “riot,” and even “ri-bellion” to describe what happened 50 years ago, but the “rebellion” in the title of this feature is not a reference to the incident. It’s rather an allusion to the subversive spirit of those who were generous enough with their time for this entertaining oral history. Find more detailed narratives from this uncommon group of freethinking Detroiters here.

Charles Simmons: Why did '67 occur? What led up to that? When I start thinking about it, well, the coming of Columbus was the beginning of it. There's an unbroken continuity of struggles against injustice all the way back to that period. [laughs]

Harvey Ovshinsky: It started when we took Belle Isle from the Indians. It's inherent. Detroit was an American city. It has American problems. And slavery is the curse of America. Until we work it out, it's just going to bite us all in the ass.

Charles Simmons: It's like Langston Hughes said: "What happens to a dream deferred? Does it dry up like a raisin in the sun? ... Or does it explode?"

Harvey Ovshinsky: It was incremental. It was both big and incremental, but mainly it was incremental. I mean, how much shit can you put up with before ... You put a pot of water on the burner, and if you don't lower that heat it's going to boil over. And that's what happened.

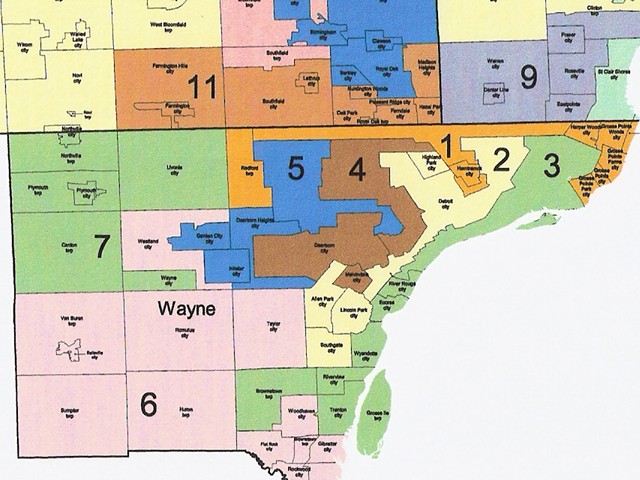

Charles Simmons: There were so many issues. Economic issues: At that moment, you've got the speed-up in the factories with the new technology. There was also the Vietnam War. And we're seeing this war on television, and then we've got the soldiers going back and forth, and they're sharing their experiences about racism in the military, as well as the racism at home. Discrimination: We didn't have any black foremen or any black people working in the offices. And then you've got the housing stuff. We were paying high rents. And, earlier in the decade, the City Council had actually voted to support segregated housing.

Peter Werbe: Just 24 years earlier, there had been this horrible race riot in Detroit, and so the contradictions of race were still really throbbing. You add to that the beginning of the disintegration of the economic structure and this brutal, corrupt police force, and it's a prescription for what we saw.

Herb Boyd: Relations between police and black Detroiters have a long and troubled history.

Frank Joyce: Enough can't be said about the politics of the white police as an occupying force in the city of Detroit. This notion that it was the job of the police to sort of keep control of the black community in general, and black males in particular, was a very entrenched feature of life at the time.

Harvey Ovshinsky: There were two policings of Detroit citizens. If you were black, you got one style of policing, and if you were white, you got another style. If you were white, you didn't worry, you respected the police. If you were black, it was another story.

Peter Werbe: We always got treated very badly by the Detroit cops. Even when I was 13 and 14 years old, these cops regularly would stop us and steal our cigarettes. They'd say: "Got my pack today, Pete?"

Frank Joyce: Joining the civil rights movement was eye-opening in many ways, including being with black people when they had police encounters, which were, of course, nothing like anything I'd ever experienced, in terms of the hostility, the fear.

Peter Werbe: We began running into cops when we were with the civil rights movement. When they attacked the group, they didn't discriminate then.

John Sinclair: I don't know if they had 10 percent black officers. I'll bet it was less. Certainly in the command structure, there might have been two blacks.

Reggie Carter: The police department was overwhelmingly white, and even the few blacks that they had on the police force had a reputation for viciously assaulting blacks.

John Sinclair: They knew they were wrong, too, in terms of policing the populace in a rough, and rude, and illegal manner. So I guess they expected something to happen. They had to. They were probably shocked that it took so long. [laughs]

Some of the roughest, most illegal policing came from elite units known as "the Big Four."

Frank Joyce: The Big Four were beefy white guys who rode around in Chrysler 300s. They were correctly reputed to have in the trunks of their cars an arsenal of shotguns and other weaponry beyond the pistol and nightstick of the average beat cop.

Peter Werbe: They were just the meanest, ugliest, stupidest guys you'd ever run into.

John Sinclair: The Big Four could do whatever they wanted. They were patrolling the black community to make it safe for the white merchants, and landlords, and city government, and white people in the suburbs.

Charles Simmons: I knew of the Big Four since childhood. And I witnessed them beating up people, young teenage boys. Young black guys would stand out in front of the pool halls. Standing outside, in the black community, is a cultural thing. But the police would threaten you and curse at you and say, "If you don't give me that corner, I'm going to kick your ass when I come back, motherfucker." That was their style. The composition of the Big Four was one uniformed white dude and three big brutes in suits, and they had baseball bats, billy clubs, brass knuckles, all sorts of torture stuff, and they would whip your ass. And God forbid they should take you to 1300 [Beaubien St., Detroit Police headquarters]. You'd just get stomped, and you were lucky to leave there alive.

‘He was throwing a bottle because of slave ships and chains and whips and what have you that coalesced right in that moment.’

tweet this

Herb Boyd: You knew when the Big Four was cruising around the neighborhood, really harassing and intimidating people, saying, "You're kind of dark over here, gang. You better get away from here." It was like a continuation of the plantation experience, you know — unlawful assembly: too many black people in one place. We may be plotting, scheming to do something. So we were always wary of that growing up, even in our little doo-wop sessions under the lamplight in the North End. Because we knew: They come through, they'll hit you upside the head if you disobey.

Harvey Ovshinsky: We had been reporting on the relationship between the police and the black community for a while. The troubles that were brewing were not a surprise to us.

John Sinclair: They just harassed you at all times. And the thing about hippies was, like black people, you could see them. You could tell them by their long hair, different clothes, headbands, so we stood out against the landscape, and that was all they needed for "probable cause," you know? In our neighborhood around Wayne State, you couldn't walk from one side of the expressway to the other without getting stopped. And they'd go through your pockets. "He's gotta have some weed in his pocket." And usually you did.

Leni Sinclair: They would stop and frisk anybody they didn't like. They called us names, like "longhairs." But we just kept on doing what we were doing. The only thing that they could hold against us — and did us in eventually — was the marijuana laws. I mean, making poetry and music were not against the law. But smoking a joint is. And it was so much against the law that they used that to bust John three different times.

Against the backdrop of repressive policing, Detroit was a fermenting hotbed of liberation groups. Far from dampening the expectations of inner-city residents, the unfair conditions seemed to radicalize people.

Reggie Carter: In 1967, I'd had some exposure already to radical politics. I had an older brother at the time who was involved, and I was heavily influenced by him. Detroit, primarily because of the Great Migration, was a center for social movements. It had [the] Nation of Islam, the Republic of New Afrika, black Christian nationalism with Albert Cleage, the All-African People's Union, Grace and Jimmy Boggs, Dan Aldridge, what emerged as the Dodge Revolutionary Union Movement, the Pan-African Congress. Ed Vaughn's bookstore on Dexter was a hive of activity, where anybody with a social conscience came through at one point or another.

Charles Simmons: There was something wrong with the economic and political system that had to be changed. Organizations like the Black Panther Party, Uhuru, and the League of Revolutionary Black Workers, and some of the SNCC [Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee] people, the activist youth of the 1960s, raised some fundamental questions about the system that our elders in the civil rights organizations did not address. NAACP and CORE — their position was that desegregation was the solution, period. And after that, we'll live happily ever after. But they couldn't restrain the young people. In the '50s and '60s, the youth didn't want to hear anything about "go slow." Martin Luther King appealed more to the older people and the Southerners. But Malcolm X appealed more to the young men in the North.

Herb Boyd: We realized we could go ahead and flex our muscles politically and otherwise. We were empowered and emboldened, I think, to a great degree. And of course it was happening internationally too. We were being fed and energized globally because of the winds of change that blew across Europe, Asia, South America, and, of course, the African continent, and many of us began to connect with revolutionary movements across the globe. Those were very powerful symbols of change and self-determination, and many of us bought right into that. Hey, we thought the revolution was right around the corner.

Charles Simmons: So you've got the Vietnam war, you've got economic conditions that are physically brutal, and racism, and, because of segregation, we generally only interacted with whites who were police.

It's cumulative. You could never say, "It's going to happen this year." Every year they would announce, "Well, there might be a riot this year, when it gets hot." You know: Negroes like to come out and riot in the hot weather. [laughs]

The mostly young and white radical contingent had created a small community at Warren Avenue and the Lodge Expressway, with the Detroit Artists Workshop, the Fifth Estate offices, the Committee to End the War in Vietnam, and a couple of Victorian townhouses dubbed "the Castle." The group's own troubles with the police were already boiling over.

Leni Sinclair: On Jan. 24, 1967, the whole Detroit police department came swooping down, "Lightning Dope Raid on Wayne Campus: 56 people arrested for marijuana." Oh, man. Including myself. The next thing I know I've got handcuffs on, and I'm off to jail with 55 other people. [laughs] And my case got thrown out by Judge Cockrel. And everybody else's case got thrown out. They were only after John Sinclair. They had to arrest 56 people just to arrest John. Yeah, those were the "good old days."

John Sinclair: At the end of April we'd had our maximum hippie event, a Love-In on Belle Isle. The police raided it and drove everybody off the island. So that was our relationship with the police. We hated them. And when the black people rose up against the police, nobody could have been happier than us.

Leni Sinclair: I remember how it started. The evening before the rebellion, we were invited to a party by people who had a house on Grosse Ile that extended over the water. I remember it was kind of the very tasteful, classy, laid-back atmosphere of the beautiful people. The lady of the house had a long dress on that was topless. At the time, even fashion was rebelling. And then at midnight somebody took us on an enchanted walk through this incredible garden at night. It was just mind-blowing. And then we went home, and then the next day it started. I just remember that it started with such a beautiful evening.

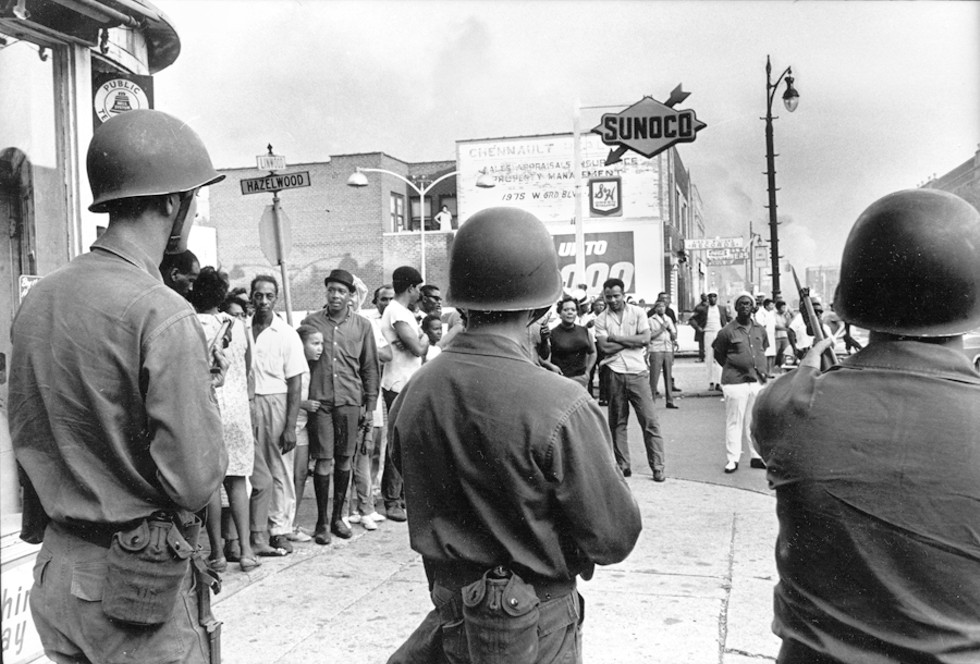

In the early morning hours of July 23, 1967, a crowd confronted a police raid on an unlicensed bar — or "blind pig."

Peter Werbe: There were longstanding grievances. When that man threw that bottle at the cop, it wasn't just because he was a little pissed off. He was throwing a bottle because of slave ships and chains and whips and what have you that coalesced right in that moment.

Charles Simmons: What happens in a riot is that all of those years, decades, centuries of abuse just explode.

Reggie Carter: When police went up in that blind pig, they found more people than anticipated at a party for returning black vets from Vietnam. Police made the decision to arrest these people. They went off and fought a war. You come back and this is how you get treated. You put your life on the line for a country that you come back to and nothing has changed.

John Sinclair: It was just a party at an after-hours joint. They weren't hurting anybody. Booting those people out of the blind pig at 5 in the morning into the paddy wagon, people just said, "Wait a minute. Fuck this!" and started throwing shit at them. And then they set some shit on fire and they overturned some police cars, and then people said, "Wow! Finally! It's bustin' loose!" That's the way I looked at it. You heard about this isolated incident, at 12th and Clairmount, and by the time you heard about it at noon it was already raging. Raging!

Pun Plamondon: The corner of John Lodge and Warren was a real center of the community in a lot of different ways, aside from being a gathering place at the Detroit Artists Workshop. It was the real heartbeat of the community, and I just happened to come down one morning and was asked if I heard about the riots.

Charles Simmons: I was sitting on the porch over [on Wabash Street] when it started. I saw smoke and then I saw people coming around with shopping carts full of stuff. [laughs] I ventured out ... I think neighbors told me there was a riot going on, and then I heard about the curfew.

Herb Boyd: When the thing went down, I was living on Richton between Lawton and Linwood, about 10 blocks north. That Monday, as soon as I heard it happened, I jumped in the car with my two sons. In fact, while we were driving around, we ran into Kenny Cockrel. [laughs] We ran into Kenny out there. And we had a nice discussion about what was going on, and then I drove on off and started to survey and look at all of the stores and people. I mean, there was still a lot of action in the street, because this was early, before the police or National Guard or any kind of Airborne could come in there and do anything.

Reggie Carter: I wanted to go out in it, and my stepfather stood at the back door and said, "You aren't going anywhere." He and I didn't get along the best, but I thank him even today for that. Because I had no reason to go out in it. Anything could have happened.

Frank Joyce: On July 23, 1967, I was in London, England, at the Dialectics of Liberation Congress, meeting with people from worldwide liberation movements. As news of what was going on in Detroit was reaching London, all of a sudden I became a person of interest in a way I had not before. Here I am at a conference where people are talking about anti-colonial struggles all over the world, and then come the headlines of Detroit in flames and troops being called in. And I was frantically trying to rearrange my travel to get back to the United States!

Harvey Ovshinsky: Where we were, the Warren-Forest area, the looting was more like a circus.

Herb Boyd: The A&P and the Kroger, some of the larger outlets — they didn't have a chance. People running up and down, cars pulling up, loading up with all kinds of groceries. If you were near anything like that or a pawn shop, or jewelry store, or something like that, it was obviously like a domino effect.

Leni Sinclair: We published some fliers during the rebellion. One of the fliers said, "Loot: It's the American way!" [laughs]

Peter Werbe: On the front page of the Fifth Estate was the headline "Get the Big Stuff."

John Sinclair: We went over on Trumbull and did some looting. We had our Trans-Love Energy cars that we used to ride around the neighborhood and pick up hippies and give 'em free rides. We saw you walking down the street, we'd stop and pick you up. That was our concept, you know? We were hippies. On acid. [laughs] So we would give people a ride with their goods that they'd gotten from the store. [laughs] We'd drive them home. We got a few goods ourselves. I remember we went into a store on Trumbull by Forest. It was a yard goods store.

Leni Sinclair: I have a picture of someone from the Artists Workshop walking down the street with a bolt of material that he had liberated from the five-and-dime. For years afterward, we used that material to sew band clothes for the MC5. [laughs]

John Sinclair: If you showed a picture of them, I could tell you which parts came from the store.

Peter Werbe: Harvey and I were out in the streets and found no hostility toward us whatsoever. We were around Trumbull and Forest, which was an integrated neighborhood, so there was integrated looting. And I remember Mayor Jerry Cavanagh took a tour while the riot was going on and said he was horrified there was a "carnival-like atmosphere." And I always wondered, "What did he want? Did he want it to be like a race riot like 1943?"

Harvey Ovshinsky: The looting was biracial. [laughs] ... The looting was permission to fight back anonymously, in a way that you couldn't get caught. Because things were out of control. I mean, when Peter and I were down there, we couldn't believe what we were seeing. There was a picture in the Fifth Estate that covered the riot of this young kid — he must have been 13 or 14 – carrying a rifle around. That was weird. It was a Fellini movie.

Peter Werbe: At the A&P [supermarket] at Trumbull and Forest, there was a young black kid about 12 years old, the whole front window was shattered and people were entering, and he had all these bags. And he would snap open these bags, like a bag boy, and hand them to people going in. [laughs]

Herb Boyd: People wandering down the street with a mannequin? I mean, come on. Just to grab something. Like mismatched shoes!

Leni Sinclair: When the rebellion started, on the first or second day, I think, we had a ball. We thought that it was just the greatest. We could drive down the street ignoring all the traffic signs. There were no cops. There were hardly any people on the street. We would see fires and everything.

Pun Plamondon: I guess you could say this was thrill-seeking: John Sinclair and I rode for three or four miles on the wrong-way side of the Boulevard, which was just unique. It was just unusual; there were no cops around. Where were the cops? The cops were out protecting the white property or firemen putting out fires. So if you were away from the action, it was true freedom.

Peter Werbe: My favorite counterculture thing was that people were playing out of the windows, "Light My Fire" by the Doors. And the cops would go running into these apartment buildings on Prentis, which was, like, student housing from one end to the other, trying to find out who was playing it.

Pun Plamondon: Have you ever gone 100 miles per hour in a car, squealing around corners and throwing gravel, losing your hubcaps and then you end up at the bar saying, "Man, wasn't that cool?" That's what it is, it's just a rush of dodging the cops. If you get caught up in it, you either get grief from the police or get shot or firebombed.

Leni Sinclair: And some of the hippies who lived in the Castle took a TV up on the roof, probably a case of beer, and were watching the riots on TV, and at the same time you could see the fire. I thought, "Wow. This is great." [laughs] But you know, that was in the first moments of rebellion. You think this is the end of the old order and the beginning of the new!

Pun Plamondon: Me and my wife at the time, we crawled up through the ceiling; there was an access door in the attic, and we got up to the roof, where you could see what looked like about 12 blocks or 15 blocks that were on fire. When you looked to the east side you could see fires. And then in about two hours you looked back to the east side and those fires had doubled. Fires on the west side had doubled. When you looked down toward downtown, you could see Grand River was ablaze. We were just smoking joints, listening to tunes and making reports to each other.

Peter Werbe: That's right! I haven't thought about that. We went up on top of the roof of John's apartment. And people were dropping acid too, which wouldn't have even occurred to me to do. And I just remember seeing fires everywhere. It looked like a city that was being bombed. And I remember thinking this was the end of Detroit.