Like many of us this year, I’ve found myself searching for hope anywhere I can find it. I’ve found it, in part, in Detroit’s arts community.

Listen, I know it gets said all the time that Detroit’s creative commonwealth is “vibrant” and “thriving” and “rich” and all the other adjectives that, while true, have become cliche from hollow overuse. There is, however, one word that can’t be said enough: Detroit’s arts community is essential.

Detroit’s arts community is not essential because it buoys the economy, or makes Detroit welcoming and desirable to outsiders, or brightens the walls of our city with pleasant decoration. It does do all of those things, which are important. But those positives don’t rise to the same significance as a bus driver shepherding people to work or a farmer keeping food on our tables.

Where it does — why Detroit’s arts community is essential — is because the act of imagination is the first step in creating a new world. It seems almost too obvious to state, but so simple as to be frequently missed: If we’re unable to first envision a new way to live, we will be unable to create one.

Artists are professional imaginers, and art — especially in Detroit — is not simply agreeable window dressing to a city and culture. It is the initial act of creating a new, better world. And this year has shown us how desperately we need one.

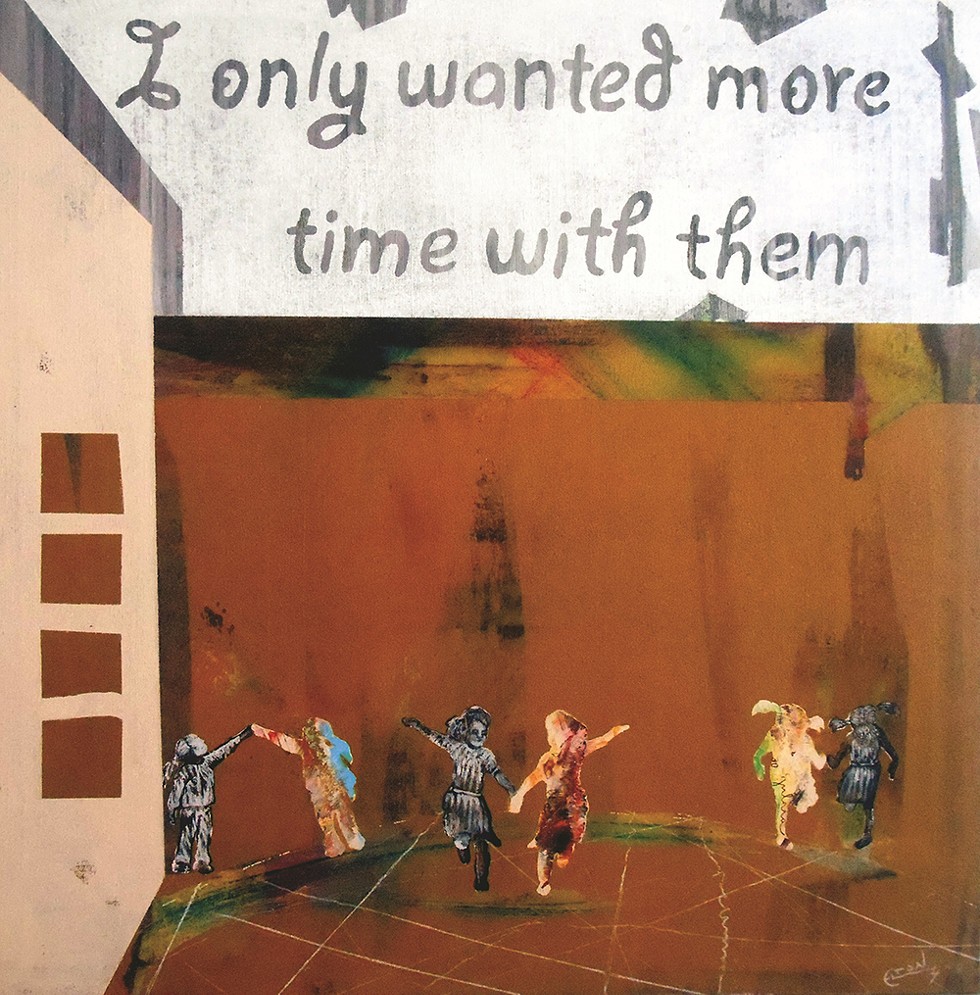

While hope and beauty and aspiration make up the bedrock of these stories, there’s a vein of anguish running through them this year, as well. The theme these artists were asked to create around is “connection,” and many of these pieces highlight life in its absence: the grief of lost love, of coming home to a home you no longer recognize, of wanting more time.

But these are the lamentations that only grow from the deep soil of interrelation itself. They are the cries of mother-responsibility, the spirit of Detroit demanding to be heard, the songs that rattle the cage-bars of complacency and punch the bitch-warden of America’s unique brand of arrogance and irresponsibility square in his fat, red nose. These stories are the dark soil of possibility in which the light is nurtured and grown.

It is in the voices and names within these pages, the voices and names across our region, relentlessly creating in the face of disease and death and all of our other contemporary nightmares who weave our ashes into the beauty of what comes after this profound sorrow.

Listen to these voices of our creators. It’s in them our salvation lies.

—Drew Philp

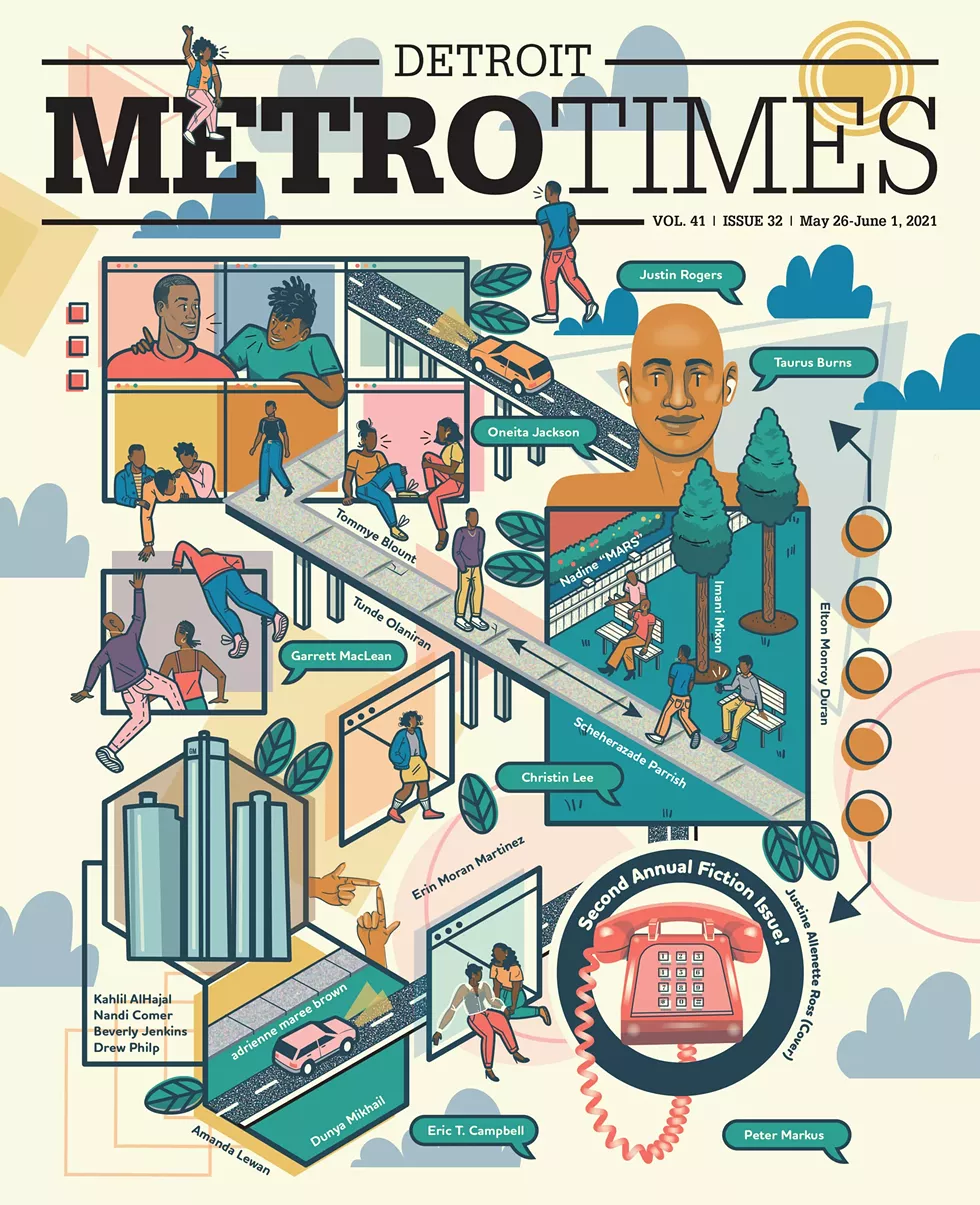

This yearly Fiction Issue receives generous financial support from Kresge Arts in Detroit. Drew Philp is this year’s editor and Nandi Comer the deputy editor. Justine Allenette Ross is the cover artist.

Kresge Arts in Detroit is generously funded by The Kresge Foundation and administered by the College for Creative Studies. The goals of Kresge Arts in Detroit are to enrich the quality of life for metro Detroiters by helping artists provide a broad spectrum of cultural experiences; celebrate and reflect the richness and diversity of our community in all its aspects; heighten the profile of arts and artists in our community; and strengthen the artistic careers of local artists.

That Place

By Dunya MikhailI want that place

and you in it as always:

how you remember my flower

kept in the refrigerator.

I want that place

and I in it as always:

the candy moon we put

under our pillows

to dream of those who will love

us tomorrow.

I know the trees

in your garden and how they grow

quietly like grandmothers,

and how the gravity pulls light

into your hands.

Dunya Mikhail is an Iraqi-American poet and writer. "That Place" originally appeared in In Her Feminine Sign, published by New Directions in 2019.

Fly in a Coney Island

By Khalil AlHajalPulled in by a gust of wind through a doorway propped open to cool customers, a housefly zips around a Coney.

Disoriented by the indoors, he lands on a balding head, nestled safely between stray hairs.

He gains his bearings and listens for a moment.

"You ever eat a pickled egg with pop rocks in your mouth?" his jovial host asks another diner seated two stools to his left.

"No," the man replies, plainly.

This won't do, the fly decides, retaking flight in search of something more comfortable.

He lands on a muffin.

"Everything is horrifying, and it's a wonder we aren't all running around screaming with our hands in the air all the time," says the muffin's owner, to no one in particular, before shoving the banana muffin in his mouth.

The fly escapes just in time and moves on down the counter, eavesdropping on one halfway voluntary conversation after another.

"If squirrels had thumbs, they'd be way ahead of us as a species. They'd have spaceships and sugarless sugar by now," he hears from atop a soggy french fry.

There's some polite laughter, and the fly moves on.

He eventually finds the perfect spot, on a drop of spilled, sugary tea, next to an aromatic bowl of tomato basil soup.

"God is good," says his latest host, closing his eyes thankfully before spooning into his soup.

A quiet moment is broken by the next man over.

"Is he?" asks the next man down the counter, shaking his head energetically. "I'm not so sure, sometimes."

"The devil is a liar," the religious man responds, softly.

"Sorry," the other replies, sipping his coffee. "I just can't relate. I'm an atheist. I'm a non-believer — but I respect religious people, I do. You know? I don't advocate for atheism.

"I don't want to convince ANYONE else not to believe in God. That's horrifying. We need religion, you know?"

The religious man nods quietly.

"We take for granted," the talker goes on, "that we aren't all slitting each other's throats in the night to steal each other's salt.

"We think, 'Do people really need religion? Do we have to believe in fairy tales in order to be motivated against killing and stealing? Are we really that low-down as a species, that we have to make up a higher power just to keep us from cheating and swindling and murdering our neighbors every chance we get?

"But you know what? The answer is yes. Yes, we do. We do need a real reason to be decent. A reason to be afraid to do wrong."

The religious man slurps loudly, as does the fly, hoping to drown out the talker.

"Maybe some people don't," the talker goes on. "Maybe if you've lived a sheltered life, you have a natural inclination to be good to other people ...

"But some of us ... some of us will kill you."

The religious man, for the first time, stops slurping his soup, slightly turning his thick neck for a side-eyed glance at the talker.

"If there's no God, and no Heaven," the talker goes on, "I'm not mowing my lawn. Why should I? If a person doesn't believe in divine reward and punishment, but still feels the need to respect his neighbor and his neighbor's property, just because you happen to have been raised well and believe it's the right thing to do — THAT's the cult. That's the weird crackpot phenomenon that saps get suckered into — not religion. Religion is the rational way to go.

"If there's no God, I'm coming for your jewelry. I'm coming for your women. I'm coming for your throat. I'm getting ahead ... Sorry. Is that scary? Sorry."

"You wanna know what the really scary part is? I am an atheist!"

THWACK!

The religious man, scowling from head to toe, annihilated the poor fly with a rolled-up newspaper, clutched tightly in his hand as he glared directly into the eyes of the talker — who could see the fury of God in the religious man's wide brown eyes and flared nostrils.

The talker, now quiet, wide-eyed, but meek, goes back to sloppily eating his coney.

A waitress disdainfully slaps a pair of bills in front of the talker.

"You're paying for his lunch, Al. It's the right thing to do."

Al nods.

Khalil AlHajal, a news editor at MLive.com, lives in Southwest Detroit with his wife, Emily, and cat, Moonshine.

What I Only Want

Elton Monroy Durán is a muralist working on community-engaged public artwork that highlights Detroit history and cultural identity.

Motes (an excerpt)

By Christin Lee

In the beginning I thought with some relief: I will no longer have to have friends. The man I loved had some version of this thought, too. The day that everything became untouchable, my courage took the form of visiting three grocers for chicken. Suddenly everything was under a slip of disease. WIPE DOWN YOUR PHONE, my friend messaged, it's 10 times dirtier than a toilet seat. The man didn't come to dinner that night. The next day he told me that his mother was sick, and there were many things that were important to him. On this invisible list he kept in his head, he told me I was last. Everything else was so pressing that he only managed to post one photo on his Bumble profile that day.

There was a morning I looked out my window to the Lodge and nothing moved. For long stretches of time, the valley was empty and silent. The groundhog was in no hurry to scuttle across the yard. I noticed that I was waiting, like I was seated for a test. I guessed an answer: Americans drive out to the quiet, it isn't supposed to come for us.

Strange reports registered on the body. A rash across the arm, an ache under the skin that roved like a ghost in your house, frantic and eternally tethered. My eyes hurt, they just hurt, from trying to understand too much. In the mornings I sat in a soft wingback chair and read every news item through to the last sentence. I read medical journals and comprehended nothing. No exceptions, I thought, now this is your holy work.

One day I saw a woman I knew waiting outside the grocer's. She was a writer, married with young kids. When she picked apples on the other side of the citrus island, mask tight, I looked at her to say hello. I sensed she kept her eyes down deliberately. Her body was tense and I understood. The rules were different now. I could see that our suffering would remain separate, and I could feel a new logic of emergency taking hold.

Another day, I cradled my phone. One more emergency resolved, house quiet. I'd stopped taking amphetamines in the morning. I wanted a truce with slowness. Gone were the litanies I'd recited to myself, gone was any bitterness, the soft music of my fears and slights against me. For the moment, each intimate friend was safe, housed, fed. I was overcome with love. I felt the gold dust of serenity settle over me, but then the future went slack. There was still a frantic animal in me panting at the door. Thoughtlessly, from bottom to top, I licked the smooth black screen of my iPhone.

I tried to understand why I loved the man so much. It had to do with seeing. I had come to believe that everything I saw in the world, he saw too. Two eyes collapsing into one field of vision, making everything deeper, sharper. There was great happiness; I had never known this kind of trust.

Washing dishes with the news on, I looked down from my kitchen window to see a boy playing in Bob Sestok's sculpture park. Cicadas made their jazz, and Bob's welding buzzed along in the middle of the morning. The boy was absorbed in some fantastic, invisible world. He had chosen the tallest sculpture in the park to be his enemy. He was ecstatic and guileless with some stick or sword. I watched him stab and retreat until he would fall to the ground, wounded, defeated, dead. Then he would jump up, circle, stab, and fall victim to the towering assemblage again. I felt convicted by a bad metaphor. Everyday I wear myself out on the unchangeable. I thought, hey kiddo. You and me, why do we issue ourselves so many defeats?

The season grew warmer. The anguish ... for now there's no writing it down. If you put your hand on your chest, you can still feel it. You could rake and dig and water, but the anguish was the only thing that grew.

The more I saw my friends in squares, the more frightened of them I became. Two inches by two inches. All that flitting by. Was it that I knew them to be so much bigger? Did seeing them miniaturized disorient me? I lost my talent for touch. I slept in the shape of a cannonball.

On the Fourth of July, my dad called me as our small party devoured the bread, salad, potatoes, and lamb. We passed the shrooms. I excused myself and walked into an empty side lot. I paced the perimeter of the chain link fence as we spoke and slung my tears away from my chin. The house party down the street smelled like hickory smoke and sugar. The fireworks were deafening like war. When I came back to the picnic table someone asked, Do you guys talk very often? No, I said, I thought he was calling to tell me he was dying or something, but he just wanted to tell me that he loved me and he was sorry the past between us was so hard.

The next day I drove to Belle Isle. On the bridge I saw a man sitting on the roof of a Tahoe, legs dangling through the sunroof. The car went faster and faster as he punched the sky, joyful and alive, riding his catharsis like a chariot into the sun. I met my friend at the beach when the shadows were going long, the crescent bellies had burned, and heads lolled back on lawn chairs. She waded into the water and laughed to brace against the cold. A boy drifted toward us on a pool noodle. He wanted to know our names. Hello, we said. More children came, pushing my friend to the periphery as I stood in the middle and tried to keep up with their questions. It was six conversations at once. One boy was five, one boy was six, one girl was seven, two girls were eight. It's your birthday? Happy birthday! How long have you been swimming? I see why you think Spiderman is the best, but I disagree. No, I'm much older than that. Do you know how to float? I crouched down with the water at my shoulders while my friend waved to the mothers on shore. Did they want us to play? It seemed all was well, the children could stay in the water. The girls drifted off and I pulled the boys back and forth on the noodle. Let me show you something, I said. I'll teach you how to float. Both boys shivered in the water. I opened my palm and the youngest fell back and stretched his arms out, eyes big and trained on the sky, blinking. I've got you, can you hear me? Yes. Do you hear the river? Yes. What does it sound like? He laughed, I don't know! Arch your back, chin up, relax. The small of his back grew lighter on my fingertips. You're doing so well, do you want to keep floating? Yes, he said. He closed his eyes. I was grateful for what touch can't say: I wanted a child so badly, but the right man never came. For the hour, the gods of shame and violence looked away, and the sky gathered its purple clouds around us. We all swam under small, evaporating lights.

Christin Lee, director and founder of Room Project in Detroit, received her MFA in fiction from the University of Michigan.

EIGENGRAU

By Nadine "MARS"you sleep and your father

appears with half a face

sits in a corner of your bedroom

and watches your body

tense, just as it did when

you were twelve waiting

for his belt to strike your

flesh for your tired mouth

failing to say good morning

in a night filled with the restless

song of crickets you wish

to ask him what it's like to die

alone

to fall amongst the prick

of freshly cut grass and

simply disappear

even here, your father never

loses his gaze toward you

doesn't extend his gangly arms

to beg you to come closer

what do you call a man who is there

and still absent

spectre

what do you call a dead father you wish

could speak

phantasm

*

you search

for remnants of a woman

once known to you

who sang you to sleep

with a honeyed voice

her arms rocking you

in the half light

you call out to her

yes I was

once your daughter

and I am no more

or yes I want to fall

in love too and document

the Hyacinths in spring

your mother, who is no gardener

says you make her proud

in spite of all that goes without

saying you wish to bring her

close so close

you wish

to ask if she'll ever return

Nadine "MARS" is a writer and cultural organizer born and raised in Detroit.

Chapter 1

By Beverly Jenkins

Central Africa

1800

Aya loved being human. As the daughter of the Sun and the Moon, she had the ability to take on any form: an eagle in flight, a leopard chasing prey, a honeybee seeking nectar. By shrouding herself in flesh, she could walk among the people of the villages, relish the warmth of her mother rays, enjoy the gentle kiss of her father's night breezes, and savor the solid strength of Africa's soil beneath her feet. As a human woman, she'd witnessed childbirth, learned the art of cooking, planting, and the songs that mourned the dead. As a male, she'd joined the hunts, woven bolts of beautifully colored cloth, and posed as a warrior to a king. Her mother, the Sun, cautioned her against spending so much time as someone other than herself, but Aya, filled with youthful arrogance and hubris, chose not to listen.

On the day that would change her life, she learned a local village would be naming its king's infant son. She especially enjoyed celebrations. No matter the occasion, there were always delicious foods to eat, skilled musicians, songs, and dancing. As night fell, and her father, Moon, rose in the sky, torches were lit and the revelry began. Aya had just joined the circle of women for a dance to honor the child's mother when a horde of men brandishing swords and guns rushed into the torch-lit village. The king's warriors took up their spears and shields to meet the foe. Chaos ensued. People ran. The screams of women and children filled the air. The intruders were slavers, a pestilence that had been scouring the continent for decades. Aya was forbidden to intervene in human affairs, but seeing the newly named baby snatched from his wailing mother, she raised her voice to chant down the whirlwind, only to be felled by a crushing blow to the back of her head.

When she regained her senses, she was lying on the ground. The sun was high in the sky. Groggy, head throbbing, she started a chant to return to her true form, but pain doubled her over instead. There was iron encircling her ankles. It was the only man-made substance capable of binding a Spirit, and it burned like hot coals against her skin. Fear grabbed her. Looking around, she saw that she was not alone.

Seated nearby were hundreds of men and women shackled by leg irons and tethered to each other by lengths of heavy chain. Slavers stood over them, guns at the ready. Her fear increased. To her shock, shimmering behind the faces of some of the captives were other Spirits of wood, air, fire, and earth, who'd apparently been masking as humans, too. Now, like her, they were caught and powerless. There were also demon spirits, who though bound, smiled greedily from within their human facades in anticipation of feeding upon the misery and terror. Aya closed her eyes and sent up an urgent plea to her mother for help but received only silence. She pleaded, begged for forgiveness. Again, nothing. The enormity of her plight was staggering. She had no idea where the slavers were taking them or why. Being immortal and considering herself above the petty worries of humans, it hadn't occurred to her to enquire about the fate of the thousands of Africans taken captive before. Now, she wished she had done so. A short distance away sat scores of chained children. Their anguished cries tore at her heart, and she wondered about the fate of the king's son. But it was her own fate that was most chilling. Until she found a way to be free of the iron, her true self would remain trapped.

She and the other captives were dragged to their feet and forced to march days on end, their destination unknown. Some died along the way. Those who balked or could not keep pace were shot and left behind.

Weeks later, she and her exhausted companions found themselves on the coast and were fed into the belly of an enormous wooden ship bobbing atop the water like a waiting beast.

Beverly Jenkins is the recipient of the 2017 Romance Writers of America Nora Roberts Lifetime Achievement Award, as well as the 2016 Romantic Times Reviewers' Choice Award for historical romance.

Poor You, It Isn't Going to Be Easy to Slake Me

By Tommye BlountRetouched, a double-tapped vision:

this white man's countenance;

then, underneath it, another: monument

of whiteness—one makes room

for another; one jawline rightward

shifts; the gaze of the other eyes

me, as if it wants to put to rest

not a lesson in pillage. An admission

—don't make me

say it—to say there are waves of bodies

shifting, a bed rocked by the "primitive,"

loopholes in their biology, no holes

in the white sails, more holes in the sheets,

the held ghosts of so many

forced entries and exits negotiating

each other; a future made of nothing

but churned whiteness. Is it not a chain;

this historical feed of I want

what I want? And do I not want to be

more than witness, to be closer

to this white chin, under its cover,

a white with which to lie. Can you hear me,

blond head? Lie against me in the bed

you didn't make. Like your great great grandfather,

touch my unmastered face—

I promise to know nothing—check my teeth,

my nose—don't I too have your nose?

Oh, baby, you've got my nose

opened in your eyes' deep blue

of good boy, good boy. It's too late to leave,

come back to this bed; get back under

the soiled sheet. After all this time,

am I not still thirsty for your hooded cock?

Tommye Blount is the author of What Are We Not For (Bull City Press) and Fantasia for the Man in Blue (Four Way Books), a 2020 finalist for the National Book Award, a 2021 finalist for the Lambda Literary Award in Gay Poetry, a 2021 finalist for Publishing Triangle's Thom Gunn Award, and others.

The Pause

By Amanda LewanSomething dangerous was in the air. Stay home, they said. It was safer there. In an effort to keep busy, they walked at lunch or at dusk. The light shrunk faster in the fall. The trees, gold and glowing, were lowering and releasing to the ground. There the dead leaves gathered. The cold set in.

Walking they saw their alley, filled with weeds to the knees. The spaces near them were often left overgrown. This was Detroit, post-bankruptcy, a city in repair. Elena didn't like to think about the alley. Tucked behind a tall privacy fence, she had grown used to not looking at it.

"It's unused. Let's do something," her husband said.

That next weekend they trimmed it down. Elena went inside and strung old balcony lights, big bulbs hanging down a black line. She found two folding chairs and a table. She brought out beer. They sat down, pleased with themselves.

"What will I do now?" she asked.

"You'll find something," Mattie said.

"I wish I could just be a stay-at-home mom."

"Don't. It will happen again."

Elena thought of her layoff. It had come no matter how hard she tried. She worked underneath the donor director of the museum. Her boss laid out the virtual events revenue. People didn't want to pay for a screen. The dollars and visitors were gone. Mattie made enough to hold them over. She knew they were lucky, but the words wouldn't come out.

Soon, neighbors came to their alley. They saw the lights on and brought their own chairs. They sat spaced apart to avoid the airborne disease. It came and went quickly and silently, symptoms or no symptoms. They were afraid to touch one another. A hand shake, a hug was all it took to pass it between people. Outside, it was safer. Their neighbors Marsha and Raphael sat across from her.

"We closed the dining room today," Raphael said.

"That must be hard," Elena said.

"They're like family to me," he said.

"Remember what this place looked like before?" Marsha asked. "Businesses on every block before the fire."

"They never rebuilt it?" Elena asked.

"Nope. My grandfather lost his grocery store that year," Marsha said. "We'll survive. We have to."

Raphael leaned across, grabbing another beer.

The days passed with less and less to do. The warnings remained the same. Stay home or outdoors. Do not invite others into your house, where it spreads faster, contained and encouraged. Elena hated being indoors too long. She found solace in the alley, a usefulness, hosting neighbors here. Mattie worked late instead.

"I'm worried about you," he said.

"I'm on a pause."

"When will this be over?"

"God only knows."

"Not the pandemic."

One night she sent a text, and no one came. Raphael was working carryout. Marsha resting for a big story. Elena drank alone in the alley until she heard the sound of an engine's distant thrumming. Drag racing was not rare. They saw it before, a block of cars, a self-made barricade for the sanction of the race. Elena leaned down and felt the cold dirt vibrating. She looked up expecting a headlight, but saw only dark sky. She wasn't sure how far or close it had been.

She went inside, shaken. Mattie was asleep. When she looked at her husband, eyes closed, she saw their baby girl. He had stopped talking to her about their stillborn. This was the silence in the house between them. Elena had held her once. She had touched each finger, kissing them. Elena had known her daughter alive, kicking inside her. Then, the kicking paused. Without a warning, she knew. Something had gone wrong inside of her.

***

"When tragedy hits, it never makes sense."

Marsha was telling her the story she just reported, a sixteen-year-old shot and killed.

"Does it ever hurt? Telling these stories?" Elena asked.

"What hurts is hoping for change. Sometimes you can taste it like it's coming. Then, you taste nothing. Things stay the same."

"Maybe they will get better."

"Maybe is more heartbreaking."

Marsha had lost her aunt and cousin to covid. Her cousin managed a grocery store and took the disease home. It spread to her aunt and uncle; only her uncle survived. Marsha counted sixteen members of her Black community she had lost. As much as things changed, Marsha feared the same. As much as they were neighbors, they knew two different worlds crossed here. Marsha was Black, and Elena white. Marsha lived it. Elena sat at a safer distance.

"Do you think the mother could have saved her boy?" Elena asked, tears beginning.

"Are you alright?"

Marsha held her as they cried, masks wetted at the edges.

"I can still see her eyes closed."

"I can still hear my cousin's voice," Marsha said.

"Mattie says we have to move on."

Marsha sighed loudly.

"He thinks differently," Elena said.

"He fills his day with work."

"I have nothing left to fill."

Outside, Elena could breathe. She could remember. The baby in her arms. The fear in her belly. It had switched. It had stirred in her glass. It had sunk her. Inside, Marco saw her puffy eyes. He closed in.

"It wasn't your fault," he said.

Elena nodded, letting him hold her.

When winter arrived with the first snow, Mattie closed the alley bar. The chairs went back in the garage. The lights turned off. Elena stood outside staring at that tall hovering wooden fence, the alley behind it. She watched her breath turn to fog. She'd live through this, somehow, she knew.

"When you're ready," he said.

"I know."

"500,000 deaths and counting," he said. "We're lucky."

"We are," she said.

They were still alive. Her daughter was still born. Elena was still waiting, but the pandemic continued. Mattie found her in the kitchen when he told her the latest news: her grandmother had it. He reached for her hand. She felt an urge to vacate her body, to find the alley. Instead, she looked at Mattie. She gave in, holding him.

Amanda Lewan is a writer and small-business owner living in Detroit. She is currently writing a fiction series exploring privilege during the pandemic.

Sweet Violet and the Heartache of Sacrifice: A Story to Be Read Sunwise

By Erin Martinez

“I willfully take of the most precious, grace-filled beauty of Creation, for the sake of preserving my own life; yet when I attempt to reciprocate, my sacrifice seems so trite and insignificant in comparison. I am left in a state of longing to give all of myself. This heartache is without reprieve, so long as the sun rises and sets; so long as I breathe.”

Erin Martinez is a mother, homeschooler, visual artist, crafter, educator, singer, dancer, arts administrator, and feminist entrepreneur, who has been living and hustling in Detroit for the past 13 years.

What Feathers We Might Find There

By Peter Markus

Those places that he walks alone

or with his dog are like rivers

you can't step into twice.

The tracks left behind in the snow

or mud are mostly his own.

What if the birds crossing the sky

left evidence of wing-flap,

of beak-song. How would star or sunlight

break through such abundance?

What fine lines of symmetry

might we find there. What symbols

to decipher. The desire to choose

between water and air, tree and dirt.

To rise suddenly, largely unseen,

when what is a not-bird comes too near.

How we stop and look skyward with an envy

that plucks the heart of its feathers,

that pulls the not-winged among us down.

The rubber muck boots we walk in

sinking deeper into the mud.

Peter Markus is the Senior Writer with InsideOut Literary Arts and has a new book, When Our Fathers Return to Us as Birds, forthcoming in September from Wayne State University Press.

Untitled

By Eric T. Campbell

Editor’s Note: On the very day Metro Times was to ask Eric to participate in this issue, he had a stroke and was incapacitated. He is regaining his strength, but this space has been intentionally left blank in honor of Eric and his commitment to the Detroit community, as well as in remembrance of all of those who, over the last two years, have had health issues, all those we have lost, and those lacking health insurance.

Excerpt from Grievers

By adrienne maree brown

[Excerpt from Grievers, a novella by adrienne maree brown, set for release in fall 2021 to launch the Black Dawn Fiction imprint at AK Press]

Dune let herself get close to the model city, the four tables covered in little plastic trees, patches of green felt for open space, small buildings gathered from board games, trinket stores, her own abandoned toy collections. It was always summer on the model. It was her first time really taking it in as an adult.

Standing north of the city, the basement stairs behind her, she could look down Woodward all the way to the blue silk scarf that was the Detroit River, the city's southern border, a major barge thruway. She moved around in a circle, walking down the eastern edge of the model. Standing at the river, Canada at her back, the tall GM/RenCen buildings were at her waist, the Greektown casino near her right hand. Opposite her, beyond the North End, waited the wooden stairs up to the open basement door and her mother's world.

This was her late father's realm.

Brendon had done an amazing job of re-creating the city. Downtown was built to scale. Dune recognized the massive L shape of Cobo Hall, the Westin a few inches north, the People Mover frozen on its useless circuit. There was a switch somewhere that was supposed to turn it on, but she couldn't remember if Brendon had ever gotten it to successfully chug its loop.

Her prescient father had argued on behalf of real public transportation. It had come, imperfectly, in the form of a light rail a couple of years after his death. It was supposed to expand to the west and east this year, actually reach neighborhoods beyond the gentrification zone. She wanted to tell him.

Though, maybe nothing would happen this year. Beyond the newest virus making her people sick, Detroit had been rationing water for some time — not for lack of water, but because of greed and mismanagement. Two years ago, the city council had finally implemented a rightsizing plan, denying services beyond the downtown area, creating havoc and resistance north, southwest, east.

And beyond the city borders? The country was imploding along fault lines of race and fear. The norm was stolen elections, rampant corruption, a bought-and-sold media, gutted and turbulent schools, and a never-ending and unclassifiable world war.

A crumbling age. Maybe nothing would ever be built again.

Dune leaned closer. North of the defunct train, I-75 cut a path along the upper edge of the stadiums. Brendon had spoken of hooking up light and sound to the model and being able to recreate game nights, though Dune didn't get it. He'd always said it was the worst thing that happened in Detroit, getting swarmed by drunken White people from the suburbs who threw beer cans all over the downtown streets and stopped up traffic, honking in tones that were identical in victory or defeat.

Maybe, probably, games were canceled due to the Syndrome.

Dune hoped. A shadowy upside.

Just above 75 was an area Kama and Brendon used to take her often, to look at, to long for: Black Bottom. The stunning houses were mostly empty, boarded up or shelled out by arson, but Kama had told Dune stories of the elegant Black people who had lived out of those homes, where each family was a part of the city's glamour. Kama had often spoken of growing up and having one of those homes, on the block where Joe Louis and Sugar Ray Robinson had been neighbors, or the home where Delloreese Early was born years before she became Della Reese.

Brendon had glued multiple smaller house pieces together with curved Lego attachments to approximate the unique structures they loved. His makeshift neighborhood signposts had the oldest known names of places on the bottom, moving up, each slip of paper a newer name, occasionally with gentrified hood brands in sardonic quotes. In the center was the largest sign, which said, "Detroit (pop. 1,942,567)." Under this was "Fort Pontchartrain du Détroit," then "Le Détroit du Lac Érié," and finally "Anishnaabe/Kickapoo territories, Mound Builders."

Who were the Mound Builders? Dune didn't want an internet search response. She knew she missed her father when she came across these questions that would never be answered, not in his way. He told stories to say a word.

Above the highway, maybe 1/4 up the model, was Mack, which became Martin Luther King Boulevard once it crossed the central meridian of Woodward heading west. It was no fancier for the formal name. The entirety of Mack/MLK was pockmarked with potholes that were refilled each spring, re-formed each winter, strewn with drug detritus and napping drunks, so that's what her father had recreated.

Her father had done a particularly good job recreating Eastern Market, the largest open-air farmer's market in the country, tinfoil and brick sheds with lots of small flowers and fruit piled underneath. Dune and Brendon had volunteered at the Grown In Detroit stand together every summer of her teenage years, Brendon interviewing every customer about their Detroit stories, Dune rolling her eyes and gathering cash.

Back across 75, two blocks west and six blocks north, stood the house she'd grown up in, the house she sat in now, nearly alone on its block. Gerald and Nina's bright purple house sat across the street, with two languishing apartment complexes on opposing corners, fenced in, as if they had valuable things inside.

Dune touched the model house that her father had made into their home — it was just a little Monopoly game house glued on top of a flat Lego, but Brendon had brought her and Kama downstairs when he painted it. She could see him now, his face soft with pleasure as he gripped the little building in tweezers, dipping it into the actual sunbright yellow paint they'd used on the house's facade, and placing an X on top with a mangled paper clip. Detroit was his treasure map, home was his gold.

His placement was specific. Dune knew her parents had been proud of this house, of holding a radical enclave in the heart of the Cass Corridor. They had never adopted the "colonizer name" of Midtown that was cast over the neighborhood in the erasure trends of gentrification. Her parents had loved their outpost, even as they watched the heart of Detroit go pale outside their windows.

Now sunlight was shining on the model house. Dune looked around, trying to see if there was a hole in the wall or ceiling somewhere. There were no windows down here ... but there was sunlight, a bright, active beam on the small house. Dune waved her hand over the house, but could not block this light.

adrienne maree brown is a writer living in Detroit.

Meyers & Plymouth | Detroit, MI 2004

By Justin RogersMe and my friends lived on

Meyers a two lane street lined

with leaning trees and bungalows

connecting major streets

Joy Rd.

and

Plymouth.

We lived too far from Joy Rd. to call it ours—

instead we praised Plymouth—

"P-Rock"

Chanted this on playgrounds.

Painted it on industrial dumpsters.

We wanted to own something

Our piece of Plymouth was unheard of

but we knew P-rock was the rawest

way to consume all of Detroit:

Liquor store pizza and hot fries.

Traps posing as penny candy stores.

Boys on the bus draped in Pelle Pelle.

When the Pistons won the '04 finals

our parents stood in the potholes singing

"We Are the Champions"

loud enough for the Joy Rd. boy's

candy paint Caprice Classic

to prowl down Plymouth playing

the song in-between Slum Village and Jay-Z.

That summer we were only left wanting time

to stop so we could steep in our joy,

so we could own a version of Detroit filled to the brim

with victory

Justin Rogers is a Black Detroit writer and author of Black, Matilda (Glass Poetry Press 2019).

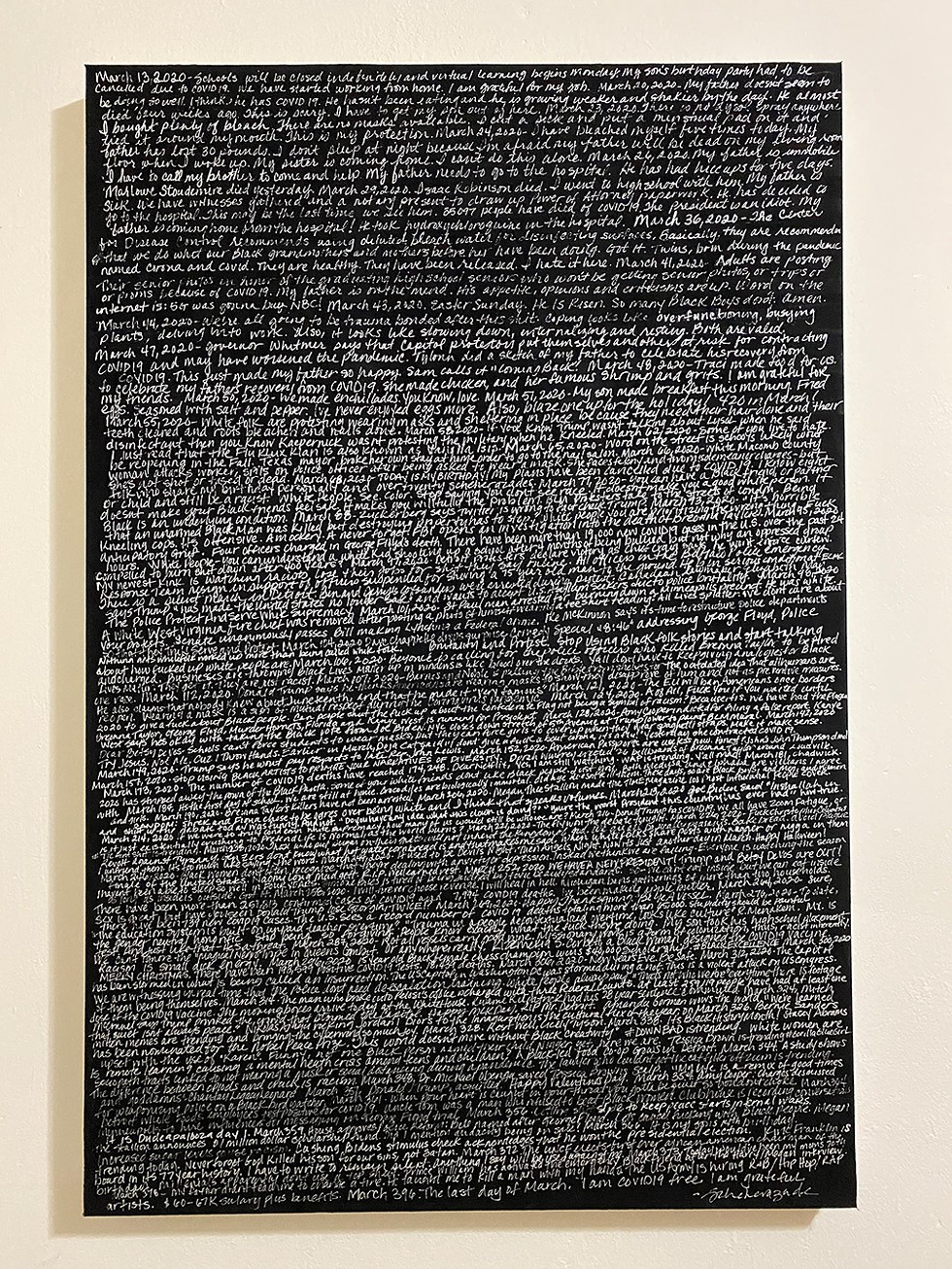

The Year of March

By Scheherazade Washington Parrish

“March 13, 2020-schools will be closed indefinitely and virtual learning begins Monday. My son‘s birthday party had to be canceled due to COVID-19. We have started working from home. March 23, 2020. There is no Lysol spray anywhere. I brought plenty of bleach. There are no masks available. I cut a sock and put a menstrual pad on it and tied it around my mouth. This is my protection. March 24, 2020- I have bleached myself five times today... March 55, 2020- White folk are protesting wearing masks and sheltering in place because they need their hair done and their teeth clean and roots bleached and nails done. March 58, 2020- if you know Trump wasn’t talking about Lysol when he said disinfectant then you know Kaepernick wasn’t protesting the military when he kneeled. March 62, 2020- some of you live to hate. I just read that the Flu Klux Klan is also known as Vanilla Isis. March 65, 2020. Word on the street is schools likely won’t be reopening in the Fall. Texas mayor broke her own stay at home order to go to the nail salon... March 93, 2020-“it’s horrible that an unarmed black man was killed, but destroying property has to stop“ White people you are prioritizing the wrong thing. Fuck kneeling cops. It’s offensive. A mockery. A never forget...March 112, 2020. Donald Trump says he thinks Americans are wearing masks to show they disapprove of him and not as preventative measures. He also claims that nobody knew about Juneteenth, and that he made it “very famous“. March 121 2020– the EU will ban Americans once borders reopen. Wearing a mask is a sign of mutual respect during the coronavirus pandemic. March124, 2020 - Fuck you if you waited until 2020 to give a fuck about Black people. March 149, 2020 - Trump says he won’t pay respects to late Rep. John Lewis. March 152, 2020 - American passports are useless now...March 173, 2020- the number of COVID-19 deaths has reached 174,248. Dear Netflix, yes, I am still watching.”

Scheherazade Washington Parrish is a mother and writer living and working in Detroit.

Fashion Forward

By Oneita Jackson

Mali Perrier backhanded her millennial colleague after she made an off-handed sartorial remark.

It was meant to be a compliment, but 50-something-year-old Mali didn't take it that way.

They were walking out of the morning meeting, a meeting about microaggressions — the irony! — when Lori Cavanaugh, the Detroit Dispatch's new investigative reporter said, "Don't you look lovely in your Natiki Dos Dos-like pantsuit?"

Mali was the "Delightfully Rude" manners columnist. During her 11 years at the newspaper, she received international journalism awards and was always on some TV panel as an etiquette expert.

The Natiki Dos Dos pantsuit was a Skittles orange, wide-legged, lined gabardine piece of ostentation with cream-and-cobalt blue Nigerian print in the front, cream in the back. Mali wore cream Balenciaga flats and a cream-and-blue, polka-dot silk Yves St. Laurent blouse with a big bow.

She looked at her MAD watch, tapped it once, and continued to walk to her office across the newsroom, pretending she hadn't heard Lori.

When her MAD watch didn't vibrate, Mali tapped it again, twice, hard. Nothing. Again. She tapped the MAD watch feverishly. Again, nothing. The batteries were dead.

Mali panicked. She intuitively felt that her tolerance levels were low, although she couldn't know for sure because her MicroAggressionDetector® was off.

Six months after moving to Detroit from Washington, D.C., Mali had been diagnosed with Post-Traumatic Negro Disorder. Her symptoms included anxiety after interacting with uneducated white people, anxiety after interacting with educated white people, and interacting with white people, in general, at bookstores, private events, fundraisers, professional events, especially in the newsroom. It seemed to Mali that white people did not do well with Black people.

Her psychiatrist started her on 65 mg. of Rebukanizol and ordered the MAD watch to keep her in check because of her inability to handle situations where she was the only Black person in the room. The MAD watch monitored the heartbeat and sent signals to the wrist to alert the wearer of increasing anger levels:

M - MILD

green dot, one vibration; ignore

A - AGGRESSIVE

yellow dot, several vibrations; address

D - DANGEROUS

red dot, hot flash to the wrist; act

The Rebukanizol-MAD watch therapy had worked.

When a new sports reporter asked her why she was in a meeting all columnists usually attended, the green dot appeared on her MAD watch. Mali ignored her colleague.

When Mali saw another Detroit Dispatch columnist at a private club she belonged to and he asked her to get his coat, a yellow dot appeared. She greeted him by name and gave him HER coat check ticket.

It worked, mostly.

Mali was suspended for a month and had to sign a nondisclosure agreement after what she did when the red dot appeared on her MAD watch; she absolutely escalated the situation.

Mali thought about how well she'd handled other uncomfortable situations with her colleagues while she rambled through her desk drawer. Lori would appear, though, before Mali could change the batteries in her MAD watch.

"I like your little Natiki Dos Dos-like jumpsuit."

"Thank you."

She had come alllll the way across the newsroom to compliment Mali.

"Yeah, I seen one just like it in the Vogue magazine last week. Well, it wasn't just like it, it WAS it, you know? Not a knock-off."

"Oh."

"Yeah, I wouldn't pay all that money for a Natiki Dos Dos."

"Oh?"

"No. I would wait for it to get to the Rage & Rag on Cass — but I don't know how you got it so fast because they just came out."

"Oh."

Mali and Natiki Dosembe had gone to school together in Washington, D.C., first to the Bessemer School for Girls, then to Dunbar University. Mali was thrilled to learn Tiki's inaugural collection would be covered in a Vogue editorial and rejected her offer of a gift.

"I'll buy it, girl, as soon as it hits the stores," she had told Tiki.

The batteries were in the MAD detector, finally. Mali smiled and tolerated her little millennial coworker from Downriver.

The next day after the morning meeting on unconscious bias — the EYE-yer-nee! — Lori apologized.

"I didn't know you wore expensive clothes."

"Oh."

"No. I don't even know how you afford them."

In addition to her award-winning column, Mali had written three bestselling manners books about microaggressions and unconscious bias, Waiting to Impale, Close Encounters of the Unkind, and You're White, So What?

And there was oblivious Lori standing there in all of her oblivious privilege, bless her heart.

"No?"

"Yeah, Micki the frumpy librarian told me you wear the finest clothes. I grew up poor and we didn't have expensive clothes. Why do you wear all those expensive clothes?"

Mali Perrier had more grace than most, but in this moment she lost all her grace, and before she knew it, she had popped the reporter in her mouth.

It was the smack heard across the newsroom.

Mali's coworkers jumped. The yellow-dot dude from the private club barreled at her, linebacker style. Mali swiveled to the left, sending the reporter crashing into the wall. She ran through the newsroom dodging reporters and editors.

"STOP HER!"

One Balenciaga flat got caught in her cuff and she went down hard.

The sports reporter beat her with a pica pole. The frumpy librarian kicked her. The metro editor threw a stack of Sunday supplements at her (and missed). The graphics editor rendered aid to precious white Lori, whose lip was busted and bleeding.

Detroit Dispatch security detained Mali until Detroit Police officers arrived 48 minutes later.

Mali was arrested. Mali was charged. Mali spent the night in jail. Mali appeared in court. Mali pleaded. Mali got off on a technicality: The manufacturer of the MAD watch had issued a recall because of a red-dot malfunction. Mali quit the newspaper. Six months after she was taken off Rebukanizol, Mali released an international bestseller: Black Hostility: 911 Reasons We Get Offended.

No. 143: Like, "-like" is not a compliment. See: "Don't you look lovely in your Natiki Dos Dos-like pantsuit?"

Detroit bus rider Oneita Jackson is a write-in candidate for City Council and author of two satirical books.

Hunger Strike for Yemen

By Garrett MacLean

Iman and Muna Saleh (sisters, Detroit residents, and members of the Yemeni Liberation Movement) undertook a 24-day hunger strike in Washington, D.C., in an attempt to force the Biden Administration to stop its support of the Saudi-led blockade of Yemen. The blockade, which began in December and has prevented all food and fuel from entering Yemen, has led to a child dying of starvation every 75 seconds. These portraits were shot on Day 17 of the hunger strike after a candle-lit vigil, which took place in front of the barricade surrounding the White House.

Iman: "I don’t think I had much of a choice. Yemen is going through a genocide, and no one knew it was happening. I had to stand up for them in solidarity."

Muna: "We brought starvation to the doorstep of the administration. I used my voice as an extension of the people of Yemen to raise awareness and end the blockade."

Garrett MacLean is a Detroit-based photographer.

Tina Turner Holds Herself Together

By Imani Mixon

This poem was inspired by this doctored photo created by Ard Gelinck, @ardgelinck.

We been here before

Wrapping our arms around each other

Our lace gloved hands

Kissing our shoulders

Hair a honey black brown

Like the teacup terriers the fashion girls wear

In their big big purses

As they steal their way bigger

I dream my way

Out of Nutbush, onto the road

At center stage

Away from him

Away from home

And call it a miracle

They look at me

As I vaseline my glisten

I am all legs and hair but somehow not human

Just glimmer

Just legs and hair and shimmering somewhere

Not feeling

Imani Mixon is a best dresser, dream catcher, and storyteller.

The First Message

By Tunde OlaniranLet me step outside.

I can feel something, but it's hard to figure out what it is. I just knew I suddenly felt too big for my couch, and for my home. I needed more space around me. I walk down my driveway and into the middle of my street.

Let me raise both of my hands and spread my fingers really far apart.

Between them I see my battered street, the houses, some trees and grass and the sky. A few yards ahead of me, my road spills out onto a busier street. In my field of vision, a dark red SUV zips between my pinkie and ring finger.

Let me concentrate.

My hands glow with a bright, pale violet energy, and the air smells like burning latex.

My hands slice through the space in front of me, slashing a ragged tear across my street, the trees, the grass, the old green Ford truck parked in front of a neighbor's shotgun-style house. Inside the new opening, it's just endless black. Is it glistening or moving? Is the black empty space or is it brimming to the surface of the fissure?

Let me reach inside. Into that tear in space.

The guy across the street that comes to cut his grandma's lawn steps out onto her front porch. He's kind of watching, but I think he mainly just wanted to smoke.

OK, let me reach inside.

Oh wait ... the black IS brimming to the surface. It gushes out and down my arm, splattering onto the pavement. I'm probably not as scared as I should be (I lived through 2020), but I am wondering what might happen next.

Let me focus.

Do I feel anything? Yes, wait, yes. Inside of the liquid, my hand keeps sliding across something that feels smooth and firm. I dig my thumb into it and feel tendons flex. It's someone's arm! I slide my hand down to a wrist, then I can feel their fingers tentatively grasp mine. I look above the tear into my sky and it's full of dark clouds. What does the sky know that I don't?

Let me pull.

Bracing myself, I pull the arm further out from the churning opening in space. The shoulder comes next, and then the face. The face. I'm looking at myself. I stare into my eyes with bewilderment. The face is thinner, with a freshly healed scar that travels from my forehead and down into my left eyebrow. I watch myself slowly observe the street, with a growing recognition, then convulse, cough up black liquid, and stare back at me, opening my mouth to speak.

Let me listen!

Tunde Olaniran is a singer-songwriter, performance artist, and writer based in Flint, Michigan.

We Are One

By Taurus Burns

When we step into the deeply personal worlds in Taurus Burns’s art, we feel the painful history of racism, capitalism, politics, and violence erupting in the present moment.

Stay connected with Detroit Metro Times. Subscribe to our newsletters, and follow us on Google News, Apple News, Twitter, Facebook, Instagram, or Reddit.