Wes Anderson has always been an epicure at heart. From the layered pastries and rococo decor of Grand Budapest Hotel to Max's packed slate of extracurriculars in Rushmore, the filmmaker has produced a suite of works that are vehicles for both halting sentiment and formal pleasure, with an air of self-awareness often subverting their softest parts. These sensations, a signal trait, extend to the best moments well below his works' surface; they're not only felt by the films' makers but realized onscreen so that they might be shared. What many decry as self-indulgence in filmic craft becomes, when captured by the camera and given to us all, an act of generosity. Like any good host, Anderson is sharing what he loves, and has lovingly prepared; while viewers can accept the offering or not, resenting it (as seems common) scans to me as an odd tack.

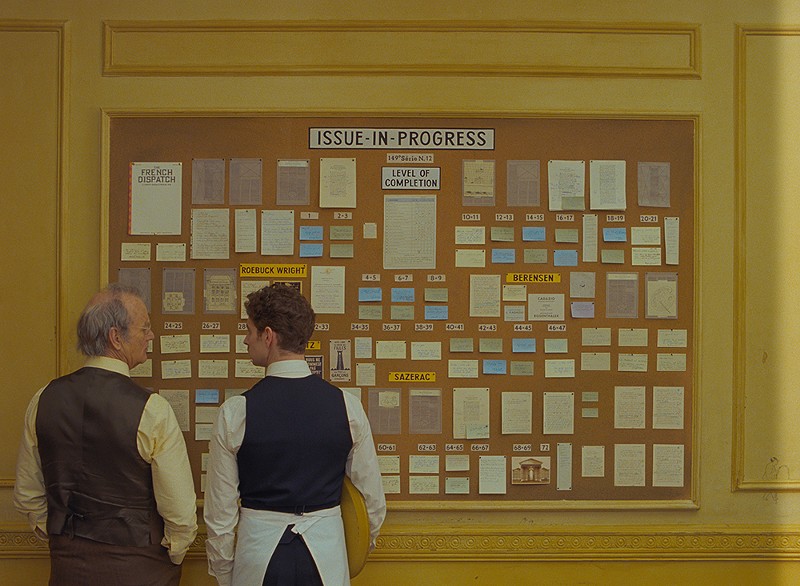

But The French Dispatch, his newest, is more than just a love letter. Capturing the workings of a New Yorker-style rag's compilation of a final issue in the mid-1970s, it devotes its time not only to the frame of editorial process — with Kansan expat Arthur Howitzer, Jr. (Bill Murray) putting the magazine together — but to the stuff the issue contains.

To that end, The French Dispatch is structured in vignettes styled after magazine stories rooted in the provincial town of Ennui-sur-Blasé (Dispatch was shot largely on location in the French city of Angoulême). A brisk, darkly comic tour of the area by avid cyclist Herbsaint Sazerac (Owen Wilson) provides an overture and sets the scene for the film's proceedings; three meatier stories follow, which take up most of the film, trailed by an obituary at the film's end.

This self-reflexive structure allows not only for variations on the film's themes but for a continuous, productive questioning (but let's not say doubt, for Dispatch is sublimely confident) of the movie itself as it hums along. Rare, purposeful pauses come amid and between the stories told, offering space for Howitzer's editorial input — with each article narrated in voices woven together from readings of a sprawling range of writers. Real-life writers like A. J. Liebling, Lillian Ross, E. B. White, and a host of others inform the film's historically rooted composite characters, who deliver a succession of driving, sharp, and credibly evocative voiceover performances: perhaps the film's best aspect and a serious achievement by Dispatch's stable of four writers. Howitzer's most frequent advice to the magazine's contributors is to convey the impression that they write as they do "on purpose": an attempt to frame irrepressible expression for readers as an outcome of deliberate artistic control.

Dispatch's default mode of metatext allows for its meditative aspects to be set into its story in a way that's tidily implicit, granting them a sense of focus as miniatures complete unto themselves. The magazine's features span a range of subjects, but each shares an attention to questions of intimacy, emotion, and the near-impossibility of journalistic and artistic distance. In the first story, an imprisoned modern painter (Benicio del Toro) besotted with a domineering prison guard (Léa Seydoux) as his muse winds up canonized by the fine art world while behind bars. In the second, an older journalist (Frances McDormand) struggles, and fails, to maintain her distance and neutrality while documenting an escalating student protest. In the third, a charismatic, musing food critic (Jeffrey Wright, evoking James Baldwin in the film's most radiant performance) attempts to profile a chef but gets caught up in an elaborate kidnapping plot. In each, the authority and sense of surety one might expect from formal writing is upended by the surprises and material realities of life — and the work — in owning up to the unexpected as journalistic truth. At the same time, the journalists' air of strained observational neutrality lets it hold certain things back, inviting a critical perspective on each segment and allowing the viewer to work on their own; it's never clarified, for instance, that viewers should take either the film's celebrated paintings as exceptional in nature — or even good.

More than the work of most directors Anderson might count as peers — and more than most of the world at present — The French Dispatch bears the hallmarks of being created by a person who reads, and reads often. Each article here's narrated with a separate sort of verbal style while feeling of a piece within the film, such that one could almost close their eyes and let the narration carry them along. While the stew of references cited here has already been denounced by some as book report-style showboating, that's a hard claim to square with the level of holistic consideration to what's onscreen, or with Anderson's willingness to question his own work. The separate segments' rhyming styles and contrasting meditations let each vignette serve as both rebuttal and complement to the rest in a way that's loosely existential. Little ever feels certain, few characters prove necessarily heroic, and any readings are contingent on a broader, often unshared context — what we're provided with here are meditations on glimpses into a fictive world. While some may take the film's various acts of withholding for coy avoidance (something Anderson's been guilty of before), what The French Dispatch offers viewers is a sense of agency instead, an ability to engage with each story's richly interrogative point of view.

Beyond the level of writing (always, in Anderson's case, a collaboration), the director's style has evolved to a level of finesse and personal peculiarity that leaves him stylistically alone among his peers, resulting in works that simply don't look like anyone else's. The Damien Chazelles of the world might ape the overhead closeups or flat-space compositions that served as stylistic signatures in his early work, and David O. Russell might try to echo his comic tone, but they can't keep up with Anderson's pace, range, or unending bag of tricks. On plain display here is a level of unforced agility and cohesive formal richness which can only be accrued over time: an artistic commodity that has to be worked for, impossible to buy. Dispatch's frames are at turns packed and spare but always deliberately composed, with the film's editorial and cinematographic techniques shifting between the dizzyingly rapid and the attentively still; its florid style is never jarring, cultivating a sense of self-awareness without being overly distant or removed. Zooms, tracking shots, elaborate freeze-frames, and slow-motion sequences are rolled into the film's fabric so finely that nothing seems like artistic affect or rootless homage.

This sense of density, balance, and authoritative grasp of form is depth in a film riddled with markers of a mature style: one in which most everything on screen (including the film's scant digressions) feels justified. Both examining and expressing the role and potency of artistic voice, The French Dispatch looks hard at the place of sentiment in writing, work, and life. The "No Crying" sign above Howitzer's door becomes by the film's finish more than just a gag, and Dispatch's few bursts of raw feeling aren't rewarded with much warmth. This withholding is no sign of shallowness but rather of thought, reserve, and care, trusting viewers to think for themselves rather than jerking at their heartstrings. Those who accept the invitation will find plenty of labor and reward here, but nothing resembling a chore.

Stay connected with Detroit Metro Times. Subscribe to our newsletters, and follow us on Google News, Apple News, Twitter, Facebook, Instagram, or Reddit.