Royal House Recording studio sits snug within an unassuming commercial area on Delemere Boulevard in Royal Oak, but walking into the $3 million studio feels like you're checking into a suite at the Sheraton in Dubai. It's as if owner Roger Goodman took his 15 years experience as a sound engineer and combined it with the best episodes of Lifestyles of the Rich and Famous. (Amenities include a car garage, workout room, and basketball court.)

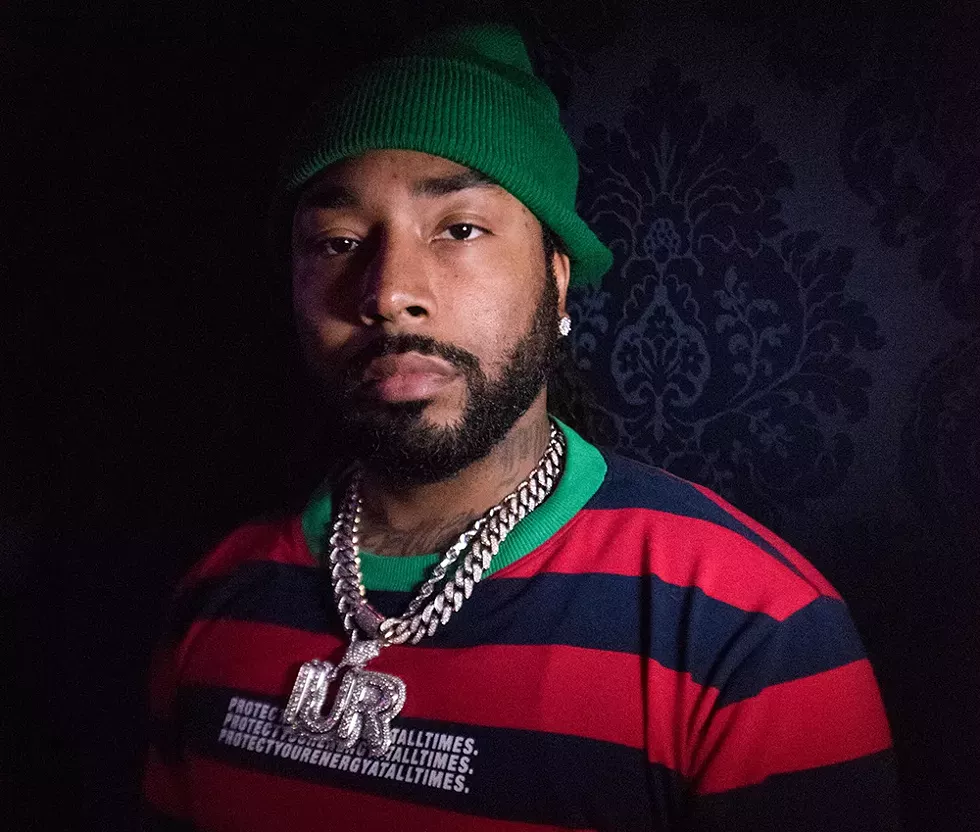

Beneath a panel of six spotlights in the studio's granite-top kitchen, Detroit emcee Icewear Vezzo is dressed in ripped jeans, Gucci glasses, and a peacoat. He's talking to his manager Chanel Domonique and the studio's operations manager Brandon Suwinski about old releases, new projects, and his recent signing to Motown Records.

He's soft-spoken, sometimes animated, but also serious. "This shit is legendary. That's history," says the emcee, who turned 30 on Halloween. "We're talking about Berry Gordy. That shit is iconic."

"They felt, 'Behind the stupid shit this brother says, he has got a story to tell,'" he says.

The passion that Icewear expresses over his deal with Motown is understandable. For one, he's the first Detroit hip-hop artist the label has signed. In fact, after 60 years and several acquisitions and mergers, Motown has only just recently truly embraced hip-hop: Icewear joins the label alongside top-selling hip-hop acts like Migos, Lil Yachty, the City Girls, Lil Baby, and OG Maco.

But it's also a radical reversal of fortune for the rapper. In April 2016, Icewear took a plea to serve two years, of which he would do 18 months, in a federal correctional facility for illegal possession of a firearm. It wasn't the first time Icewear would be incarcerated — he had four previous felony convictions and 15 misdemeanors — but it would be the longest and costliest.

At one time, it seemed like Icewear was heading to the prison pipeline. Born Chivez Smith, Icewear moved to Detroit from Minnesota when he was 5. "My mamma married my stepfather. He's from Detroit," he says as he leans back in his chair. "He was on parole so he couldn't leave the state of Michigan. They had got married and shit when he was in jail. My mamma was solid, she rolled with him the whole way. He ended up doing 6 and a half of 15 years and mama did all that with him. When he got out of prison they had to move to Detroit."

The family initially moved to Seven Mile Road and Fenmore Street on the west side for a summer and then moved east to Mt. Elliott Street and Gratiot Avenue, ultimately settling in a home on Six Mile Road and Gunston Street on the east side.

Icewear says the music bug bit him early. By the age of 12, he was writing his first raps and recording songs off the radio. "The first one was [Jay-Z's] 'Jigga What,' he says. "Nigga was rapping so fast I wanted to know what he was saying so I would record it, rewind it, hit play, and stop every three words, and write the lyrics down. I would write the whole verse down so that way when it came on I knew it word for word."

By the time Icewear was 16 he was calling himself Young Vez and trying to balance street life with his aspiring rap career. His talent was obvious, but he was racking up court cases faster than he could put out mixtapes. After getting convicted of unarmed robbery in 2007, he was ordered to submit to drug testing and not enter places that serve alcohol, but managed to convince the judge to remove a curfew from his sentence so he could continue to pursue his rap career.

Icewear pulls up his chair and rest his elbows on the counter. "Niggas was 20 and 21 rapping about living in condos and having five, six cars and wearing Rolexes, but I actually had all that shit," he says.

Icewear is just as brash as his music — confident and cocky. He's fully aware that the truths within his experiences are what separate himself and his brand of hip-hop from others. "My niggas was like, 'You got everything these other niggas rap about. The streets gon' fuck with you more because niggas see you,'" he says.

So at 21, Icewear doubled down a little harder. He started to spend less time in the streets and more time in the studio and promoting his music. That's when his Icewear moniker — named after his penchant for wearing diamonds — was born.

"I was promoting a mixtape called Young Vez Presents Icewear Vol. 1," he says. "One (of) my homies who was managing me told me I should make an Instagram page with that name. It ended up getting popular and they started putting the name on flyers for the act name instead of 'Young Vez.' I was complaining at first, but my homie told me I need to run with that shit."

He also came up with a novel way of promoting his music. "My come-up mainly started in the strip clubs. In Detroit, the clubs we party at are all strip clubs," he told Mass Appeal in 2016. "I would go to the strip club and throw money to my own music and pay the DJ to play my music. I did it so much to where my song became a regular song at that club ... to where other people would start throwing money to my music when I wasn't there."

Now, Icewear has close to 20 projects under his belt. His sound has always been classified as upper level Detroit basement sound, or Detroit trap. His approach to street lyricism is comparable to the Game, with a cadence similar to 2 Chainz, while his aura drips wet with Detroit swagger. He gives out heavy doses of witty couplets on songs like "Band Up" and "Light Show" (off 2013's Clarity 2) but has made his biggest splashes with his knack for making addictive street anthems such as "Money Phone."

"When I listen to a beat, I listen to what that beat is saying to me," he says of his process. "I made it cool to rap on some different shit. You know, 'Money Phone' is a Three 6 Mafia beat. I made it cool to switch shit up and be yourself."

"Before I came out everybody was rapping like drug dealers and wearing minks," he says. "Everybody wanted to look like the Great Lakes Ruler," he says, in reference to the late Detroit rapper Blade Icewood, "and act like Chedda Boyz," the east side rap crew engaged in a beef with Icewood that turned deadly when Icewood was fatally shot in 2005.

"I've always tried to make sure I'm really rapping, I believe in content," he says. "I intentionally try and separate myself when I do music."

At the same time, Icewear was trying to clean up his act. In 2015, he opened Chicken Talk, a carry-out chicken wings restaurant on the east side, and had plans to open a car wash nearby. As part of a community service sentence, he participated in a Crime Stoppers march, encouraging people in the community to speak up and report crimes.

But even as Icewear's catalog, followers, and views were growing, he continued to struggle to evolve completely away from street life. There was an allure and thirst that was hard to break, and it was hindering his music — although he didn't know it at the time.

Icewear pauses to gather his thoughts. "It was a real long transition," he says through a sigh. "I'm the hottest rapper at the time. I got all these songs out, but I can't stay out the streets."

"I was just so caught up on street shit. Dealing with this nigga and that bitch and just frivolous shit," he admits. "Eventually that shit led me to prison again."

In September 2015, Detroit Police officers spotted Icewear among a group of men gathered in a parking lot at an east side gas station. As they approached the group, they saw Icewear walk away, lift up his shirt, and pass a handgun — a .45-caliber loaded Glock — to someone else in the group.

As a felon, Icewear was prohibited from possessing a firearm. "I was scared, your honor," Icewear told the judge at Detroit's U.S. District Court in 2016, according to court transcripts. "I was scared of my life. My daughter was only two weeks old. Growing up where I grew up — even when you get close to making it out of the neighborhood, you get a lot of love from fans, from kids, from everybody, but the same amount of love you get is the same amount of hate you get from guys who have no hope. They don't have no future."

Meanwhile, his 2015 Moon Walken mixtape was highlighted by another viral Detroit anthem, a track by the same name, and thanks to YouTube and Instagram, Icewear's popularity outside Detroit was at its highest. His 2016 Purple City mixtape continued to explore themes built around getting money, having massive amounts of sex, and revenge against enemies.

But most importantly, Icewear had just got married and became a father two months before he reported to the Federal Correctional Institution in Lisbon, Ohio.

He says the reality of being a first-time father away from his child was the wake-up call he needed.

"At a certain point you choose who you gon' love. You gon' love yourself or love the streets," he says. "It's like overcoming any addiction. I was addicted to the streets, but my love for my family outweighed that."

‘It’s like overcoming any addiction. I was addicted to the streets, but my love for my family outweighed that.’

tweet this

His daughter, he says, changed that. "Love ain't no word, it's an action," he says. "I didn't love my child when she was born. I thought I did, but I didn't because my actions didn't show it. I just started loving my kids because I don't do things to put myself in that position anymore. And that's love."

Toward the end of his sentence this year, his manager Domonique began to set up shows and studio sessions so he could hit the ground running when he got released. A friend of hers booked a welcome home show at Saint Andrew's Hall. And an associate of that friend worked at Motown and expressed interest in Icewear.

Meanwhile, Motown President Ethiopia Habtemariam had begun rebranding the label by signing some of hip-hop's most powerful entertainers.

"When I met with her, she expressed how important it was to her and Motown to sign and actually breathe life into a Detroit artist that was truly from Motown," Domonique says.

Domonique contacted Icewear, and the minute he heard her say "Motown" he told her to "make that happen," she says.

Since Icewear was barred from traveling, Domonique flew to Los Angeles to meet with Motown's Habtemariam. "I called him for her and she offered him the deal right there," Domonique says. Finally, on Sept. 17, Icewear was able to fly to L.A., when "the deal was officially signed, sealed, and delivered," she says.

"Icewear Vezzo is someone who has solidified his place in the culture thanks to his realism and musical perspective that highlights a life lived and not just one seen," Habtemariam says in a statement. "Here at Motown, we are proud to help push this certified voice that we are confident will continue to grow in influence."

For an artist who's been at the height of his game for as long as Icewear has, a major label deal was perhaps long overdue. However, Icewear refuses to have a "What took you so long?" attitude.

"First time (I went to jail), I was focused on rap," he says. "Second time, I was focused on being a better man and better husband and a better father. The way the universe work, the way God work, He's going to align them stars if your mind right. The first time I had so much drive, but the universe wasn't aligned for me. I went at it the wrong way. I didn't get a deal then, it wasn't meant for me to get a deal then. I was focused on the things God wanted me to be focused on."

He also feels that signing to Motown will allow him to open up his musical playbook of sorts. He promises to rap with more perspective and insight, and tone down the persona that he's made himself known for. He even goes so far as to say he will leave the streets behind and only be "studio rapping now."

"I went from a real gangsta to a studio gangsta," he says. "I'm a married man with two kids watching Discovery channel now," he says, inciting laughter in the room. "There was a time where I wasn't trying to teach nothing. This time I can rap about the wrong shit, but I can turn back around and tell you what come from it in a way anybody can understand it. I want to show them young niggas what I did to stop getting high. I lost a lot of money. I didn't get fucked over, I was wrong," he says. "I fucked up and consequences came."

Icewear's new video for "2 Sides" features the rapper dressed in camo and royal blue, dropping bars about stacking money: "Counting dirty money/ Wash the bands detergent. Bitch, I been cuttin' up/ I got hands like a surgeon." Produced by Atlanta-based Zaytoven, the single is the first offering of his mixtape Clarity 6, which dropped Dec. 14.

"The beat was just so hard, I got so much love for Zaytoven," he says. "I wanted to feed the streets first. Most times when artists first get deals, their first song will be with some other multi-platinum artist."

With the signing, Detroit is at the doorstep of a possible hip-hop renaissance. Artists like Danny Brown, Chavis Chandler, Nolan the Ninja, Molly Brazy, and Sada Baby have huge followings and fanbases. Big Sean, Tee Grizzley, Dej Loaf, and Doughboyz Cashout's Payroll Giovanni are signed to major record labels, while vets Eminem and Royce Da 5'9" are still making a national impact. And as many of these artists are set to drop projects in the next 18 months, hip-hop listeners all over the world will be the recipients of the diversity and uniqueness of Detroit hip-hop more than ever before.

"There is so much talent here. The moment we come together, we're going to be unstoppable," he says. "The whole world listens to Detroit, it's so many artists from Detroit that's lit right now."

Although Icewear says he is completely focused on maximizing his current array of opportunities, he still sees his future self as a hip-hop elder statesman of sorts. He plans to reopen his Chicken Talk restaurant, which closed when he went to prison, as well as explore other entrepreneurial endeavors.

"In 10 years from now I'm going to be working with Motown, probably owning Motown with some other good people," he predicts with his signature swagger. "I'm going to be raising my children, I'm going to be working with the city of Detroit. I won't be rapping."

Stay on top of Detroit news and views. Sign up for our weekly issue newsletter delivered each Wednesday.