Carla Bley is legendary as not only a pianist and bandleader who's played with everyone under the sun, but also as a composer and arranger for bands ranging from duos to big bands and orchestras. Crucially, she was there for many pivotal moments in music history over the last 50-plus years.

Bley performs at the Detroit Jazz Festival on Sunday, Sept. 6 at the main stage, leading the Charlie Haden Liberation Music Orchestra, in what is only their second performance since legendary bassist and bandleader Haden's death in 2014. As the band's longtime arranger, Bley was an obvious choice to take over its leadership.

Born in Oakland, Calif., in 1936, Bley has been playing music her entire life. She started getting lessons from her father, a church organist and piano teacher, at age 3. As a teenager, she connected with jazz, and moved to New York City to be a part of it.

"I had to be where the music was, and at that time [New York]'s where the music was," Bley says. "So I went there immediately; there was no one to stop me. We drove across the country in a borrowed car. We had no money whatsoever but we just wanted to go see Miles Davis at the Café Bohemia. First I had to find a place to sleep. I ended up in Grand Central Station sleeping on a bench. But the next night I went to Café Bohemia. It was pure heaven.

"I got a job as a cigarette girl at Birdland, and I got to stand in front of the music stands and hear all the bands. I got to hear everybody. That was my education."

Within six months, she was composing. "I always managed to live somewhere with a piano," she says.

In the early 1960s, George Russell and others started to perform Bley's compositions. It was, to say the least, rare at that time for a woman in her early 20s to have her compositions recorded and performed by others. Many people didn't take her seriously when she approached them with pieces she had written. But she persevered. "Nothing could stop me," she says. "I'm still writing things. The music can't be stopped; it's always been that way. I can't be discouraged."

Bley was on the New York scene when artists first began to experiment with free playing. "It wasn't very good. There was a lot of people trying out things. Nothing really very palatable," Bley says of this oft-mythologized era. "I was trying out that kind of playing too and I certainly sounded horrible. I don't think anyone really got it until Ornette [Coleman] came. That's where I first liked it.

"As soon as I learned to read and play changes, I went to another stage and became fascinated. There's certain times you still would write something free, but it's not called for very much anymore, for me."

Bley was a member of the short-lived but legendary Jazz Composers Guild, a cooperative organization founded to promote new music and facilitate bargaining power with club owners. Other members included Bill Dixon, Cecil Taylor, and Roswell Rudd. Bley remembers the meetings as chaos: "It was people yelling at each other or criticizing each other. I never really yelled at anyone, except maybe Sun Ra once or twice."

"People say, 'Oh you were there in the hotbed of new music!' But I had no idea it was the hotbed of anything. I thought it was life!"

With members of the Guild, Bley and then-partner Michael Mantler formed a big band called the Jazz Composers Orchestra. It ended up outlasting the Guild itself, but continued on as a separate nonprofit organization that established its own record label, releasing records by Bley, Don Cherry, Leroy Jenkins, and more.

An important and sometimes overlooked part of Bley's legacy is the New Music Distribution Service, which she and Mantler founded as the orchestra wound down. "We weren't the first people to [release our own records], but we were the first to get an international ring together of other musicians starting their own labels," she says.

"The [orchestra] really consisted of about ten concerts. That's a small amount of work musically that was accomplished, compared to all the music that we distributed. Hundreds and hundreds of labels, for other people that were like us and didn't have any commercial distribution."

New Music Distribution Service distributed the first records by Philip Glass, Sonic Youth, and Glenn Branca, among many others. "Anything that was called new music — that was difficult and had no support — we distributed it," Bley says. "At one point we said, 'We won't even listen to it!' That was our revolution — it wasn't musical so much as business. It served the music."

Bley says she enjoyed her work as a distributor, but doesn't miss it today. "In those days I didn't write very much, because I was so busy taking care of other people's music. And now I can just write for myself all the time. In those days I felt embarrassed doing things that were only good for me to do. I wanted everything to be for the good of mankind — but now I'm just selfish. When I'm home, I write every day. I live in the woods, and I'm a hermit pretty much."

Bley says she always has a few different compositions she is working on at her home in Woodstock. She spent many years writing for and playing with a big band, but she is now focused on writing for her trio.

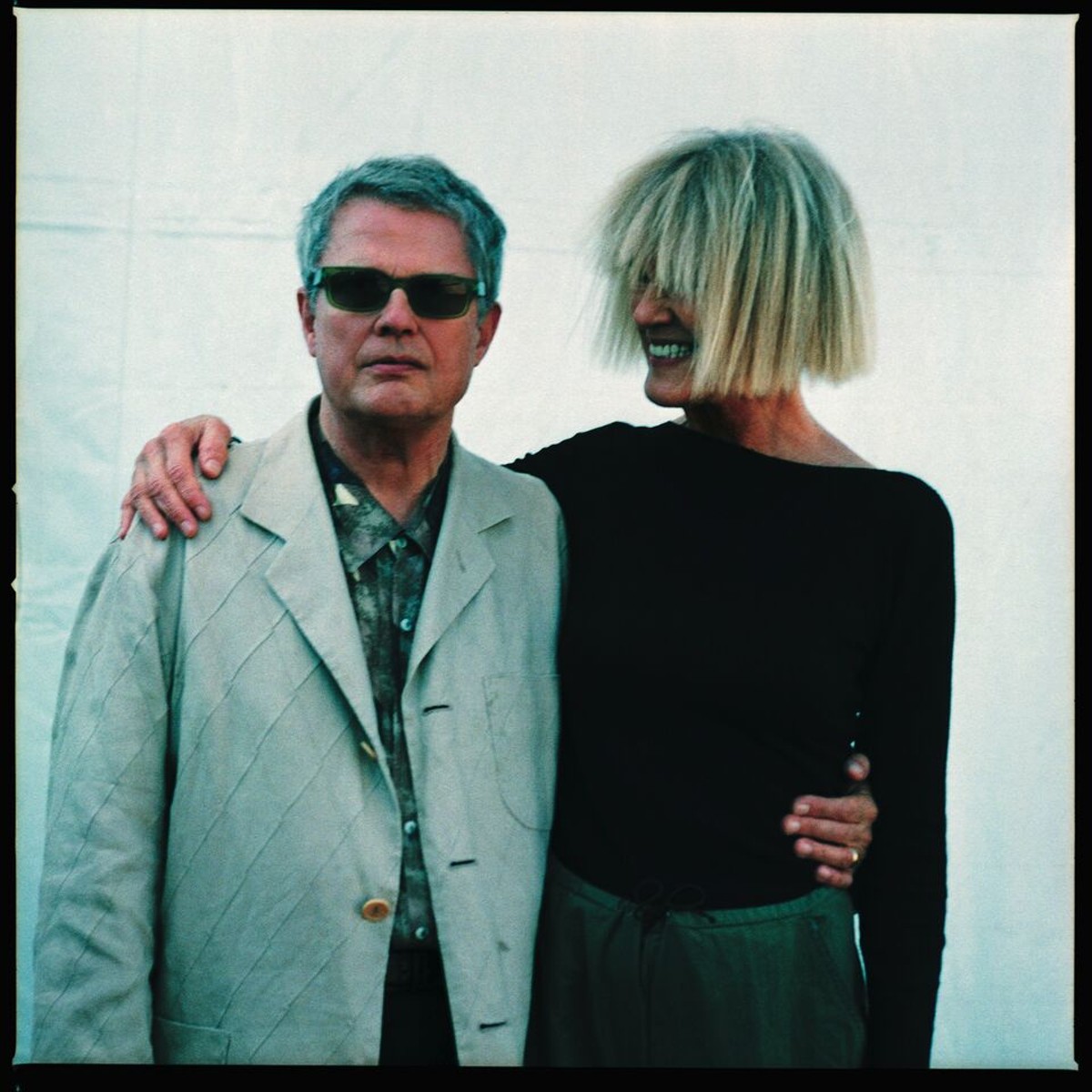

"When I write for the trio, it's really big-band music reduced," she says. "I want to work with the big band but I can't afford to do that anymore. My trio is me and two specific people, Andy Sheppard and Steve Swallow. I have to play way over my head and so do the guys. They have to take on a lot more than they would have to if I still had a big band."

The Liberation Music Orchestra is the only group Bley is working with besides her trio. She knew Haden for years in New York City before the first Liberation Music Orchestra record was recorded in 1969, and has played on and arranged for every record by that group.

"I had known Charlie because he was playing in Paul Bley's band. We had the same taste in music and had a lot to talk about, and we became friends. Paul Bley sort of collected bass players, so I got to meet a lot. But Charlie was my favorite," she says.

"Charlie wasn't doing any writing at that point; he was just working with Ornette and Don [Cherry]. And when he moved back to Los Angeles, he called me and said, 'I'm making my first record, it's for Impulse, and I'd like you to be the arranger.' And I said, 'Of course.' And it worked out really good, I thought. I'm still doing it!"

"The band that we have now is the same band that played on the last record we made when Charlie was alive, which was called Not In Our Name, and that recorded the next album which we made without Charlie, because Charlie couldn't do it anymore," Bley says.

Always a politically minded group, the upcoming album focuses on the environment, and is entitled Time Life. "We were preparing for that album and Charlie never made it; he just didn't get that far. The music was already written except for one piece. And Charlie's wife said [Haden] wanted Steve Swallow to be the bass player, and he was emphatic. Steve didn't play anything that didn't sound like Charlie. 'Cause Charlie always used to play very simply — that's maybe the hardest way to play. Everybody thought that was the perfect choice," she says.

"So I don't think there will be much difference except there's no Charlie to talk to the audience. He would talk sometimes for 15 minutes before we played. I'm a little worried about that because I don't have that skill. But this time in Detroit his wife, Ruth, is going to talk to the audience."

Bley says that after the new album's release, the Liberation Music Orchestra will be done, but she will stay busy writing and arranging, and that she has found new compositional inspiration.

"I have a new harmonic language that I'm using," she says. "I don't really know how to talk about it yet. It is really interesting to me, to the point where sometimes I'll play something and someone will say, 'That's wrong.' And I say, 'No it's not.' And they'll say, 'That's really wrong.' And I'll say, 'Thank you very much. I didn't know I still could be wrong. That does it, I'm gonna write some more of those wrong kind of chords.' That's really thrilling to me, to be really offensive after all these years."

Carla Bley conducts the Charlie Haden Liberation Music Orchestra at the Detroit Jazz Festival on Sunday, Sept. 6 at the main stage, in downtown Detroit. Admission is free. For more information, see detroitjazzfest.com.