Even for a state accustomed to navigating heavy snow and frigid winters, the polar vortex that pushed over Michigan in late January jarred the region. Temperatures in metro Detroit plunged to record lows of -26 while a dangerous wind chill hit -43 degrees in some spots, forcing school and workplace closures while confining residents to their homes.

But as the region tried to stay warm, Consumers Energy blasted out a startling warning to Michiganders' cell phones on Wednesday, Jan. 30. "Emergency alert," the text read. "Due to extreme temps Consumers asks everyone to lower their heat to 65 or less through Fri." A fire at a compressor plant deeply stressed its system, and the company didn't have the infrastructure in place to handle an emergency in extreme weather.

Consumers placed its customers between a rock and a hard place: turn down the heat during the frigid weather — or risk a system collapse that would leave southeast Michigan without natural gas to keep people warm.

Enough people cooperated that a crash was avoided, and the company said customers could turn their thermostats up on midnight on Friday. But months later, the utilities did fail. In July, powerful thunderstorms downed the region's electric service, this time as heat peaked at 96 degrees. More than 800,000 customers lost electricity, and tens of thousands would be without power for up to a week. In another 45 days, more storms pummeled DTE Energy's and Consumers' lines — 100,000 lost power, and thousands sat in the dark for days.

Public outrage followed each incident, and state leaders like Gov. Gretchen Whitmer raised questions about the utilities' preparedness as she ordered a review of Michigan's energy supply: "It's important that we get a handle on what's happened here," she said.

A Metro Times analysis of the issues found the dangerous outages are a symptom of deeper problems at DTE and Consumers. State documents show both utility companies failed to upgrade aging infrastructure, despite collecting billions of dollars annually from Michiganders during recent decades. Now, equipment in the region's decaying grid is as many as 40 years beyond its functional life. As a result, DTE and Consumers customers spend more time in the dark than those of most utilities statewide or nationally.

Moreover, Michiganders pay some of the nation's highest rates, and DTE is proposing $351 million in rate hikes — its largest yet — for 2020.

A large piece of the high bills can be attributed to wasteful overhead. At DTE, customers pay an additional $650 million annually to the company's investors, bloated executive salaries, and political contributions — that represents a 13-percent jump in costs for the average customer.

"We're stuck in this quandary with some of the fastest growing utility bills alongside the worst provision of services ... and people are really angry with DTE," says Michelle Martinez, an activist with the Michigan Environmental Justice Coalition, which advocates for utility customers in low-income areas.

While the situation is partly a result of gross mismanagement and regulatory failure, critics like State Rep. Yousef Rabhi say it's an unavoidable result of the utilities' flawed investor-based model. DTE and Consumers "exist to make money for shareholders," he says, and not to provide Michiganders with clean, reliable energy at the lowest price possible.

‘We're stuck in this quandary with some of the fastest growing utility bills alongside the worst provision of services ... and people are really angry with DTE.’

tweet this

Rabhi says municipalization — or switching to publicly owned utilities, as opposed to investor-owned — is the answer.

"If you have public control, then the utilities are accountable to voters and ratepayers instead of investors," he adds. "Right now, DTE and Consumers don't care about customers — they care about profits and bottom lines."

The idea isn't as radical as it might seem. About one-third of the nation's power is generated by publicly owned utilities, and U.S. Department of Energy data shows their customers on average pay about $18 less each month and spend about 200 fewer minutes without power annually.

As local leaders around the country grow frustrated with private energy companies, more are pushing for publicly owned utilities. Among those are San Francisco and San Jose, which are attempting to municipalize their respective grids after Pacific Gas and Electric similarly failed to upgrade its infrastructure or trim trees near its lines. Its downed wires sparked destructive fires that have killed dozens, burned entire cities, and resulted in ongoing power shutoffs.

In statements to Metro Times, DTE and Consumers defended their records on reliability and argued that their customers' bills are below the national average.

"The regulated utility model has never served our customers better," Consumers spokesperson Katelyn Carey says. "Necessary investments are required to maintain a safe and reliable system. A publicly traded, regulated utility is best equipped to raise capital in the most cost-efficient way."

However, federal data tells a different story. In Michigan, DTE's and Consumers' poor reliability and high prices are highlighted in reports from the National Energy Information Agency, which tracks the nation's utilities' rates and performance.

DTE and Consumers serve about 85 percent of the state, and Michiganders had the nation's 14th most expensive electric and gas bills in 2017. But the state ranked second worst in terms of time to restore power after an outage, according to an analysis of federal data by the Citizens Utility Board of Michigan, which advocates for residential customers. (West Virginia is No. 1.) At the state level, CUB found DTE and Consumers have among the state's most expensive electric bills, but their customers on average spent the most time without power in 2017, the last year for which data is available.

Advocates also say the current situation illustrates what happens when the state fails to adequately regulate power companies. The Michigan Public Services Commission is a state agency charged with approving or rejecting rate increases while monitoring the utilities' performance and service. The commission approved a whopping $779 million in DTE rate hikes over the last four years. That accounts for the nation's second-highest jump, yet the outages continue.

With the Public Services Commission's blessing, DTE and Consumers successfully shifted the cost burden from industry to residents over the last 10 years. While residents' electricity costs increased by about 50% statewide, industry's costs remained about the same. Consumers and DTE also convinced Michigan's Republican-controlled legislature to kneecap the state's rapidly growing home solar industry with a 2016 set of laws that devalued solar energy.

Meanwhile, Michigan's power plants are dirty. CUB's analysis found the state's plants emit more carbon dioxide, sulfur dioxide, and nitrous oxide than the national average, while renewables account for only 8.4% of the state's power — also below average.

The litany of problems, Rabhi says, all boils down to the investor-based model's need for profits.

"We are not well served by a system that puts investors first and ratepayers last," he says. "We need a system that does the opposite."

As bills go up, wealthy investors get richer

DTE's and Consumers' monthly electric rates have increased each of the last 10 years. The average Consumers customer paid $72 in 2007 and $102 in 2017 — a jump of about 41%. Those figures don't include large increases over the last two years. DTE customers saw similar increases while its next proposed hike would add about $10 more to the average residential customer's bill as soon as May.

"The report shows how residential rates have gone up steadily over the last decade ... and residential customers have an overall feeling that they're now paying really high bills and not getting the service that they paid for," says CUB executive director Amy Bandyk.

Part of what’s behind DTE’s and Consumers’ high bills are profits that go to investors, as well as executives’ salaries and political spending. DTE’s customers will pay an extra $650 million — or $13 per month for an average customer — this year to satisfy investor obligations. That means Michiganders pay an extra $13 each bill that does nothing to improve service. It simply goes to investors.

"The large companies have some higher overhead costs that the municipal utilities and cooperatives don't have," says Douglas Jester, a partner at consulting firm 5 Lakes Energy, which consults for CUB.

While executive salaries don't account for much of the overall costs, they're a point of frustration among the companies' critics. Consumers Energy CEO Patti Poppe's compensation package topped $8 million last year, while former DTE Energy CEO Gerry Anderson, who stepped down in July, received a package worth nearly $11 million. DTE's combined top executive salaries total nearly $25 million. By comparison, Mike Hummel, general manager of Phoenix's Salt River Project, one of the nation's largest public utilities, earns $1.04 million, and its top executives' salaries total less than $4 million.

Michigan's loose campaign finance laws make it difficult to determine how much DTE and Consumers directly contribute to campaigns and dark money nonprofits that attack politicians who opposed their agenda. Just several days before the polar vortex, the state ordered Consumers to stop giving money to dark money groups after it gave $43 million to a dark money nonprofit, though the companies claim ratepayers don't fund political spending. To put that in perspective, the state in September approved $143 million in rate increases for Consumers.

Some campaign contributions are made via Consumers' and DTE's political PACs, which don't use ratepayer money, but illustrate the length to which the companies spend to influence the political process. A Metro Times analysis of state campaign finance records found DTE's PAC gave to nearly every member of the Michigan Legislature during the last three years, spending a total of about $964,000. Consumers' PAC spent about $690,000 in the same period.

The companies also spend big to win over residents with everything from barbecues in low-income communities to large charitable donations. The DTE Energy Foundation spent $15.4 million in 2017, donating to a range of groups from the Michigan Historical Society to the Arab-American Civil Rights League.

At the federal level, DTE's and Consumers' PACs each spent nearly $3 million lobbying and on campaign contributions during the 2018 campaign cycle, according to OpenSecrets, a nonprofit, nonpartisan Washington, D.C.-based research group. Publicly owned utilities don't contribute to politicians.

While there's no way to calculate how much of Michigan's sharply increasing utility costs are a result of DTE and Consumers' failure to replace aging equipment during prior decades, experts say it's likely hundreds of millions of dollars annually.

The high level of funding DTE sets aside for emergency repairs sheds some light on the issue, says Ariana Gonzalez, a senior policy director with the National Resources Defense Council, which intervenes in DTE rate cases on behalf of residential consumers.

DTE told the Public Services Commission that it spent $345 million on emergency repairs in 2018 — nearly twice what it planned to pay.

‘If you can't provide energy to poor people — which is a critical service — then the whole business model is broken.’

tweet this

"If customers have already paid for this, then it should be hard for [DTE] to ask them to pay again for something that should've been fixed a long time ago," Gonzalez says.

The private-utility business model also incentivizes spending on large projects over efficiency. State law mandates a 10-percent return on investment for shareholders. If DTE spends $2 billion on a gas plant, then customers spend an additional $100 million that goes to investors because half the investment is funded with debt. Since DTE's investors are its first priority, there's more incentive for the company to spend on large, centralized factories instead of promoting, for example, efficient community solar production.

While DTE is planning several wind farms, it's investing far more heavily in natural gas infrastructure, even though methane released from gas plants is a more destructive greenhouse gas than carbon dioxide. That means Michiganders will largely be forced to buy natural gas in the coming decades, even if renewables like wind are cheaper in the long run.

"What these business models are incentivizing isn't an efficient service — it's incentivizing more building and putting things in the ground," Gonzalez says.

Prices are also high because DTE and Consumers are legally defined as "regulated monopolies." In many states, companies like DTE and Consumers would own the distribution infrastructure — the poles, lines, substations, generators, and other equipment that gets power from the plant to a house — but customers choose the company from which they buy power, Gonzalez says. That means customers could buy electricity from a hypothetical wind farm in northern Michigan instead of DTE's dirty, expensive coal plant.

In Michigan, DTE and Consumers own the distribution networks and the power plants. Because they own both and have a monopoly, most DTE and Consumers customers must buy from dirty gas and coal plants, and prices stay high.

"There's no competition to drive down cost, so it's at the discretion of Public Services Commission to decide if what the utility is proposing is reasonable," Gonzalez says.

Downed wires and toxic coal ash ponds

The power to Kiava Stewart's neighborhood near Warren and Southfield roads on Detroit's west side cuts out about three times annually. The blackouts are a part of life in the neighborhood, where many residents are low income and DTE's infrastructure is in particularly bad shape.

But when storms blew through in 2017, the lights at Stewart's neighbors' homes stayed out for nearly two weeks. Among those living directly across the street was a family with nine kids, and the food in their refrigerators quickly went bad. Stewart and the families in those homes pooled their resources, and she cooked big pots of spaghetti and chili for them while offering up her outlets.

But she wasn't done there. Stewart also organized a social media campaign, called the #BlackoutChallenge, in which she solicited donations of candles, flashlights, and food from local residents, restaurants, and grocery stores. She calls working with her neighbors to help one another a "beautiful experience," but also says it was a "severe time" that they shouldn't have been forced to endure.

The utility poles in her neighborhood look like "trees that are about to fall over," she says, and the lines are regularly on the ground.

"It's affecting us," Stewart says. "We care enough to take care of each other when this happens, but DTE should care about us enough to make sure we have what we need."

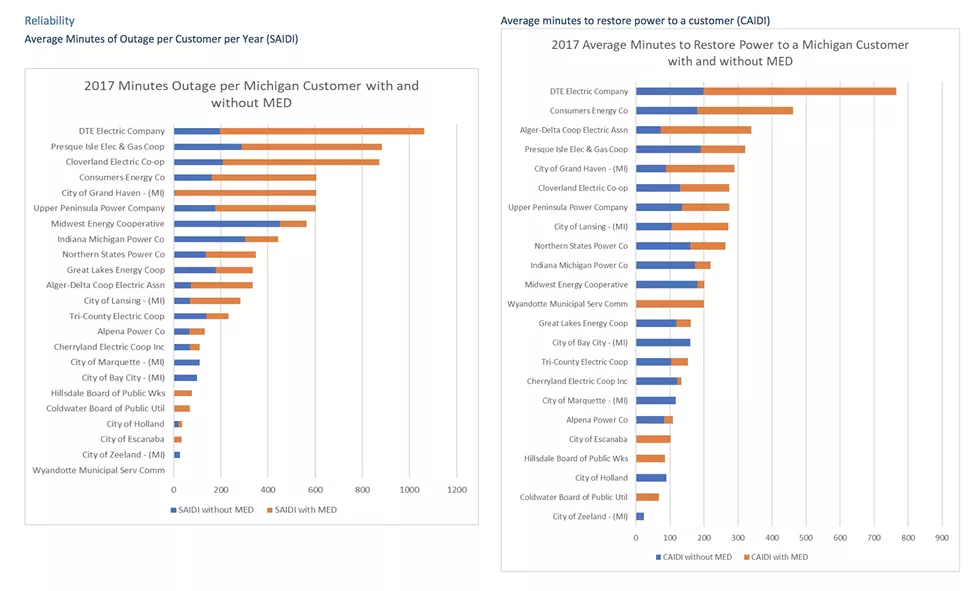

Federal data examined by CUB shows DTE customers like those in west Detroit spent more time in the dark on average in 2017 than any other state utility — about 1,060 minutes for each of its 2.2 million users, while Consumers' customers on average spent about 600 minutes without power. Data also shows that once the power is out, it takes DTE and Consumers much longer to re-establish service than the state's other utilities, and the numbers have been consistently bad over the last five years.

On the whole, Michigan's utilities are consistently performing worse than those in most other states, and DTE and Consumers are among the state's worst.

"You can see in the trends in our report that this isn't a one off problem — it's been continuing to get worse over the years," CUB's Bandyk says. In a statement to Metro Times, DTE claimed its poor performance was the result of wind storms in 2017: "Excluding major repairs, DTE power restoration times are actually better than the industry average." However, federal data shows its record when storms are excluded is also among the state's worst.

Residents in Detroit and the city's older suburbs bear the brunt of the companies' abysmal service. Many of the newer suburbs built in the 1970s and later have underground wires that aren't impacted by storms, while the infrastructure in older neighborhoods hasn't been replaced, Jeffers says.

"That part of the distribution system is in fact very old and has a lot of deficiencies," he adds. "Everyone pays the same rates for distribution but the reliability is different depending on where you are, and it's lower income communities that have the worst service."

DTE acknowledged the infrastructure issues in its 2018 rate case, but said it won't replace the old system for another 10 years.

It's now planning to "harden" the grid in low-income areas. That involves trimming trees and replacing some pieces of aging equipment. However, that solution doesn't solve the problem — it's basically a Band-Aid — and doesn't include a legally binding commitment to replace the aging system in 10 years, says Jackson Koeppel, director of Soulardarity, a Highland Park-based intervenor in DTE rate cases.

"It's a massive expenditure to harden, and for a whole decade everyone in that footprint has to deal with subpar service," he says. Ultimately, the investor-based model is inherently "classist and racist" because it disincentivizes investment in low-income, minority areas, Koeppel adds.

Despite that DTE and Consumers are responsible for the poor service and skyrocketing rates, DTE is carrying out mass shut-offs among those who can't afford to subsidize their blunders.

Data that the Michigan Environmental Justice Coalition pulled from DTE's latest rate case shows that the company regularly shuts off power to between 5,000 and 25,000 customers monthly.

"The cost of energy is so high and the resources to be able to help those who are truly in need aren't there," says MEJC's Martinez. "If you can't provide energy to poor people — which is a critical service — then the whole business model is broken."

Residents in poorer ZIP codes also pay with their health. Several of the dirty coal plants DTE operates are in River Rouge, Trenton, and Monroe. The River Rouge plant belches particulates blocks from Southwest Detroit. Asthma rates in children in those neighborhoods are four times that of most neighborhoods on the city's north side, according to a University of Michigan School of Public Health study.

State utilities also built 37 toxic coal ash ponds throughout the state that are contaminating groundwater. Testing near the sites found lead that's six times federal limits and arsenic 52 times the federal limit. The state is now monitoring the sites and imposed fees on the utilities to cover cleanup costs.

"So despite residents carrying the additional burden of the rate structures, there are also externalities that we've been carrying with the poisoning of water and air," Martinez says.

Kneecapping solar

No city in Michigan and few across the country convert the sun into energy at the rate seen in Ypsilanti. The city's solar arrays sit on residential rooftops, in city-owned land next to a graveyard, aside a high school, and on top of its city hall, fire department, and more.

All told, Ypsilanti generates 1.2 megawatts of clean, green energy across 51 installations — a per capita rate on par with San Francisco. "We're booming," says Dave Strenski, director of SolarYpsi, a group that promotes solar locally. While many residents generate solar energy because "it's the right thing to do," Strenski says, there's always been a financial incentive — a solar array could pay for itself after a few years and virtually eliminate one's DTE bill after that.

However, DTE- and Consumers-developed rules that the GOP-controlled legislature approved as part of a 2016 energy package are designed to seriously hobble the home solar industry blooming in Ypsilanti and around the state.

In short, DTE and Consumers don't want people generating their own power because the companies would lose money. The new rules devalue small-scale solar to the point that the financial incentive is significantly reduced, and that eliminates the appeal for people who aren't only in it for what's best for the planet.

"I think it'll hurt a lot," Strenski says of the changes. "It hurts the return on investment. It's as simple as that."

In a hypothetical example, a solar array owner who used 100 units of power while generating 80 units of solar energy would only pay for 20 units. That system is called net metering.

Under the new inflow/outflow system, the same person sells the 80 units they generate to DTE or Consumers at a wholesale rate, then buys 100 units back at a retail rate. However, DTE buys at rates that vary depending on the time of day, so it's still possible to earn full value, but it's far more difficult.

Regardless, it's not a good deal, says State Rep. Rabhi, who along with a bipartisan group of legislators introduced in October a package of bills that would undo the 2016 changes.

DTE and Consumers claim the changes more accurately reflect the cost of producing solar. They contend those producing and distributing energy tap into the grid without paying for the infrastructure and maintenance. The companies also attempted to tack on a $15 per month charge just for solar users to tap into the grid, but the Public Services Commission shot that down.

Rabhi says DTE and Consumers aren't considering the benefits of small-scale solar — for example, the arrays provide energy to the grid at peak times, such as on a hot summer day when the utilities have to kick on expensive "peaker plants" that provide the grid with extra power.

The companies are also targeting other sources of similar "distributive generation," or small-scale producers of renewable energy. DTE similarly devalued power generated by the city of Ann Arbor's two hydroelectric dams in the Huron River. Prior to the changes, the city used the electricity it generated and put the money it saved aside so it could fund improvements to the dams. Now, the energy it generates is purchased by DTE for $.05 per kilowatt hour. Ann Arbor then buys back power for between $.07 and $.13 per kWh.

At those rates, the city is no longer able to save as much money for dam repairs, so the dams could become a financial burden, says John Fournier, Ann Arbor's assistant city manager.

"It could force a really hard conversation about the future of one or both of our dams," he says.

Despite what distributive generation proponents say are the obvious environmental benefits of small-scale wind, solar, hydroelectric, and biomass energy, the utility companies seem intent on destroying the industries. Rabhi says that's because small-scale production is "a threat to the companies' business model and corporate profits."

"They're not concerned about the environment — they're concerned about their bottom line," he says.

(After this story was published, a DTE Energy spokesman sent us a statement saying the 2016 law was “created by a multi-stakeholder process with input from groups across all spectrums of the energy industry from environmental advocates to the utilities.” The spokesman says existing net metering customers are grandfathered for 10 years from the time they signed on under the distribution generation tariff established by the 2016 law, and that the company continues to receive applications for customers under the new distributed generation tariff. The spokesman also claims utility-scale renewables are more cost-effective than small-scale renewables.)

'We don't want to end up like California'

The crew of about 12 employees in the city of Coldwater's electric department provides power to the town's approximately 7,000 meters, and do it better than most utilities around the state.

CUB's analysis of federal data shows Coldwater residents enjoy what are among the state's lowest electric prices, while enduring among the lowest amount of time in the dark.

The department is able to provide a reliable service at low prices for several reasons, says utility director Jeff Budd. It's a publicly owned utility, so there's no profit motive to consider during planning. The utility is a manageable size, and it's proactive in replacing aging infrastructure and trimming trees.

"We don't have to have a return on investment, so when we're planning for five years out we make decisions that are best for us," Budd says. "We know our customers a little better and their needs, so we can plan a little better."

Coldwater is hardly alone — about 2,000 publicly owned utilities operate nationwide, and their prices are on average about two cents per kWh lower than those at private utilities, which translates to roughly $18 per bill for an average Michigan customer, according to the American Public Power Association.

Federal data shows customers of the nation's largest publicly owned utility, the Tennessee Valley Authority, pay some of the nation's lowest rates, as do those in Nebraska, which is the only state 100 percent served by publicly owned utilities. When New York formed the Long Island Power Authority in the late 1990s, its 1.6 million customers received a 30% rate cut.

Meanwhile, public utilities are typically more reliable and are moving toward renewable energy much quicker than investor-owned utilities. An analysis of federal data by the Next System Project shows that public utility customers spend about 200 fewer minutes without power on average.

Municipalization, while a challenging step and by no means a panacea, at the very least eliminates the profit motive and makes utilities responsive to its customers instead of to its investors, Koeppel says.

"Public utilities are far from perfect, but the decision makers can be accessed and there's a way to get them out of power if they're not acting in line with community needs," he adds. "The other piece is public utilities don't have a profit motive ... or an incentive to build as much big stuff as they can to make as much money as possible."

While there's nothing in the way of plans for new public utilities in and around metro Detroit, state leaders are taking some serious steps in pressuring DTE, Consumers, and other power companies to improve performance. Michigan Attorney General Dana Nessel is regularly intervening in multiple rate cases, which has helped keep rates lower for customers around the state. On Tuesday, Nessel called for DTE to decrease its rate, arguing its requested 9% increase is excessive and unnecessary.

“As the state’s chief consumer advocate on utility matters, I have a responsibility to ensure any rate increase is in the best interest of our state’s residential ratepayers. This one isn’t,” Nessel said in a statement. “A 9% hike request when DTE already exceeds its return on equity year over year is simply unjustifiable and unsupportable.”

Earlier this year, Gov. Whitmer announced the MIPowerGrid initiative, which asks residents and other stakeholders for input on how to improve the grid.

Those intervening in the utilities' rate cases also praised the Public Services Commission for being more responsive to residential customers' needs in recent years. Part of that has to do with a transition from the Commission having a majority of former Gov. Rick Snyder appointees on its board to a majority of Whitmer appointees.

Moreover, it's only in recent years that the National Resources Defense Council, CUB, and Soulardarity began intervening in rate cases and advocating for customers and the environment. Before that, it was mostly industry and large corporate interests that steered the rate case process.

But all the regulation in the world doesn't change the simple, base equation that forces DTE and Consumers to put profits and investors before Michiganders' needs.

"If we don't want to end up like California, then the state needs to get active fast and start thinking about" public utilities, Koeppel says. "We keep running up against this utility model that is fundamentally designed to do one thing — build a bunch of infrastructure, and this is a point in history where we need to do everything as efficient as possible."

Updated 2:45 p.m. on Thursday, Nov. 14: This story has been updated with additional comments from DTE Energy.

Stay on top of Detroit news and views. Sign up for our weekly issue newsletter delivered each Wednesday.