Michigan senators Gary Peters and Debbie Stabenow are among 16 Democrats who've joined with Republicans to advance a bank deregulation bill that progressives say would pave the way for another financial meltdown if approved. And they got a whole mess of money from the financial sector before voting to do so.

The so-called Economic Growth, Regulatory Relief and Consumer Protection Act would roll back or eliminate some of the regulations and protections put in place by Dodd-Frank after 2008. Democrats who support the bill, including Peters, a co-sponsor, say its intent is to provide regulatory relief for community banks and credit unions.

A cheat sheet on the bill provided by Peters' office suggests part of the regulatory relief for "Main Street" would come in the form a provision to increase the threshold at which banks face stricter oversight. Right now banks with more than $50 billion in assets are subject to tougher regulations from the Federal Reserve. The bill would up that amount to $250 billion, which means restrictions would be loosened for regional, mid-sized banks including Suntrust and Fifth Third.

“It was big banks and Wall Street that caused the financial crisis – not Michigan’s credit unions and community banks," Sen. Peters said in an emailed statement. "In fact, Michigan credit unions and community banks stepped up and helped keep Michigan families afloat during the financial crisis by offering credit when big banks wouldn’t."

Stabenow's talking points were essentially the same.

“Our member-owned credit unions and community banks—who did not cause the crisis—are vital to small businesses and families," Stabenow said in an emailed statement. "Unfortunately, they are starting to disappear from cities and small towns across Michigan and are facing unnecessary regulations."

But it's unclear how Michigan credit unions and community banks will benefit from an increase in the asset threshold for stronger oversight. No Michigan credit union has anywhere near $50 billion in assets — the most any of them have is around $1 billion, according to Daniel Curren with the Michigan Credit Union League, which has come out in support of the bill. The provision doesn't seem to help out community banks either; the New York Times reports the nation's more than 5,000 community banks also generally have $1 billion dollars in assets or less. The change does reportedly help out 25 of the country's 38 largest banks.

And while the 25 banks in question are smaller than behemoths like JPMorgan Chase and Citigroup, progressive Democrats like Sen. Elizabeth Warren of Massachusetts charge that they are big enough to threaten the economy if they fail. A report by The Hill points out that mortgage lender Countrywide Financial had $200 billion in assets when it became one of the key players in the financial crisis — "a stark reminder to regulators and Congress that mid-sized, regional financial institutions can put the financial system and economy at risk."

A Congressional Budget Office scoring of the bill found it slightly increases the possibility of bank failures and would likely mean more public funding for bank bailouts. The CBO projected those bailouts would cost taxpayers an estimated $671 million over a 10-year period.

Still, some provisions in the bill would be a boon for the little guys. Those include rules that would allow more small banks to operate with higher levels of debt and engage in certain kinds of speculative investment once prohibited by the Volcker rule under Dodd-Frank. There are also cuts in certain reporting requirements for banks with less than $5 billion in assets.

But for progressive Democrats, the benefits do not outweigh what they see as the larger cost of hooking up Wall Street in the wake of the financial meltdown.

"We’ve been down this road before," Sen. Warren said on Twitter. "Whenever things are going OK in the financial system, the lobbyists flood the halls of Congress & convince politicians to roll back the rules – because what could possibly go wrong?"

Warren and others have derisively dubbed the bill "The Bank Lobbyist Act" due to a provision that looks like it could help mega-banks like Citigroup and Chase take on more risk. (Peters and Stabenow, for their parts, claim the bill does not roll back any regulations on the largest banks that caused the financial crisis.) The CBO determined there's a 50 percent chance that lobbyists for the big banks will convince Federal Reserve regulators to allow them to do this (and remember, the Fed currently operates under Trump). It's complicated, but The Intercept explains it well:

Among other parts of the bill, CBO analyzed Section 402, which would change the supplementary leverage ratio, or SLR, a simple calculation of total equity divided by total assets. The section lets “custodial banks,” which do not primarily make loans but instead safeguard assets for rich individuals and companies like mutual funds, to eliminate reserve funds parked at central banks from the calculation, reducing leverage by as much as 30 percent. This would juice returns for these banks but also layer on additional risk, by allowing them to hold less equity to offset losses in a crisis.

As first reported by The Intercept, Citi lobbyists successfully engineered a change to Section 402’s language. While the definition of a custodial bank used to stipulate that only a bank with a high level of custodial assets would qualify, it subsequently defined a custodial bank as “any depository institution or holding company predominantly engaged in custody, safekeeping, and asset servicing activities."

The 16 Democrats who support the measure include centrists (Joe Manchin from West Virginia) and Senators running for re-election in swing states or states won by Trump (Joe Donnelly of Indiana, Heidi Heitkamp of North Dakota, Jon Tester of Montana, and Claire McCaskill of Missouri). Stabenow finds herself in the second category.

Both she and Peters have received quite a bit of money in campaign donations from the financial sector in recent years. According to the Center for Responsive Politics, Peters has in the past five years accepted approximately $650,000 in contributions from the securities and investment industry and nearly $175,000 from commercial banks. That's out of a total $12 million in donations that he received in that period.

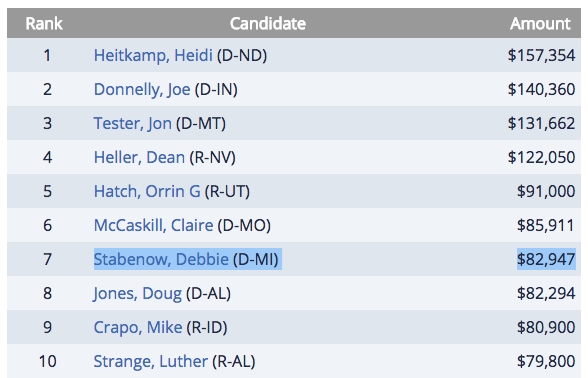

Stabenow, meanwhile, has seen a recent spike in campaign contributions from commercial banks. This election cycle, she has so far accepted at least $83,000 in contributions from commercial banks, the fifth-highest amount accepted by a Democrat and the seventh-highest in the Senate overall. More specifically, Stabenow counts Goldman Sachs and CitiGroup among her top ten donors. She has also received $485,000 from the securities and investments industry over the past five years.

Source: Center for Responsive Politics

Commercial bank donations to U.S. senators this election cycle.

Both senators missed our deadline for comment on whether the contributions influenced their vote to advance the bank deregulation. About five hours after this story was published, an unidentified spokesperson for Peters offered this quote via email:

“Senator Peters’ policy positions are driven by what’s best for Michigan’s middle-class, working families – not by campaign contributions."

With the Democratic support, the bill could pass the full Senate by the end of the week.

Stay on top of Detroit news and views. Sign up for our weekly issue newsletter delivered each Wednesday.