This much is known: Justin Pope is dead.

Pope was a 25-year-old with tours of Iraq and Afghanistan under his belt as a corporal in the Marines before being honorably discharged and taking a job with DynCorp International, a private military contractor that provided security at the U.S. Embassy in Iraq in 2007.

It was supposed to be an auspicious employment turn for the metro Detroit man — the job suited him perfectly, according to his family — but just two years after signing on, Pope was dead, killed amid his friends and colleagues in early 2009 on the DynCorp base.

His family has spent the last six years looking for answers, asking politely at first, but eventually battling with DynCorp in a three-year legal battle when they discovered the officially sanctioned and ever-changing narrative of the fatal evening never lined up with what the family had found.

The company line for the events of March 4, 2009, goes like this: A night of roughhousing and binge drinking led to an unfortunate incident. According to DynCorp, Pope — whose toxicology report later revealed he was stone cold sober — and his best friend, Kyle Palmer, were in a room on the Erbil base. A 9 mm semi-automatic handgun was pulled out. The two "playfully" fought. Palmer, who was two bottles of wine, a few beers, and several shots of Jack Daniels deep, fired off a round within inches of his best friend's face. The bullet passed through Pope's brain and out the back of his head. It was all an accident. A sad, tragic accident, but an accident nonetheless. (Palmer pleaded guilty to voluntary manslaughter and was given a three-year federal prison sentence in 2010.)

Pope's family — his widow, their 14-year-old son, mother, stepfather, brothers, and sisters — wholly disputes that account, pointing to inconsistencies in a lengthy U.S. State Department investigation into the incident as well as evidence of what they say was the contractor's attempts at covering up what really happened. (DynCorp, the State Department, and lawyers for Palmer did not respond to requests for comment for this article.) To start with, DynCorp initially told them Pope died alone. They'd later learn there were about a dozen people in the room, the size of a small office, at the time.

The tragic details are contained in a thick file in U.S. District Court in Detroit. It also includes official accounts of the homicide, handwritten letters, sworn testimony, and depositions. The trial is slated to begin later this year, and though the family remains open to a settlement — a mediation conference is scheduled in the coming weeks — they're committed to seeing the trial through to the end if it means they can finally learn the truth.

DynCorp was "coming up with whatever stories sounded right at the moment to give to the family," says Julie Hurwitz, who represents Pope's family along with William Goodman and Katie Kalahar. "As that turned out to not be true — which didn't take very long — they would come up with different stories. And every story was tainted with this overlay of, 'We have to make sure that we don't look bad. We have to make sure it doesn't come back to point at us for being blamed for what happened to Justin.' Whatever the truth is, they didn't care what impact it had on this family."

Pope's family wants what every family wants: a chance to grieve, which they haven't been able to do in the face of the uncertainty.

The lawsuit is not about "what caused Justin's death," says Hurwitz. "It's what's DynCorp did to cover up its responsibility for Justin's death, and its emotional impact this would have on the family."

'It was just a matter of time'

Torture.

That's the word Pope's mother, Patricia Salser, uses when asked to describe the feeling of being unable to cope with her son's death.

"It's torture," she says, repeating the word several times in an interview last month at her lawyers' offices.

The son she lost was an upstanding individual, a guy hell-bent on protecting others from the moment he could walk.

"Ever since I can remember, he always loved action figures," Salser says. "And he was like the sweetest little kid — he was just very kind. As he became older he just seemed to be more into camouflage and G.I. Joe and army men and wars and tents. [That] escalated into being into special books about wars and et cetera."

And that early fascination led to an early declaration that he wanted to join the Army.

"As he became older he changed it to a Marine," Salser says. "I always thought he'd outgrow it because all my children said they wanted to be something and those things changed."

But Pope was committed and his patriotism inflected all points of his life — his closet was awash in camouflage clothes, his desk adorned with a bevy of books on war.

Even as a kid, "he would wear my police shirt and badge and he would patrol the neighborhood and stop kids from walking across the street without looking, and then let them go," says Bill Salser, a former police officer who married Patricia when Pope was 7 years old. He and Patricia would hear stories about Pope's heroic career in the Marines, when he spent time patrolling the streets of Iraq and Afghanistan.

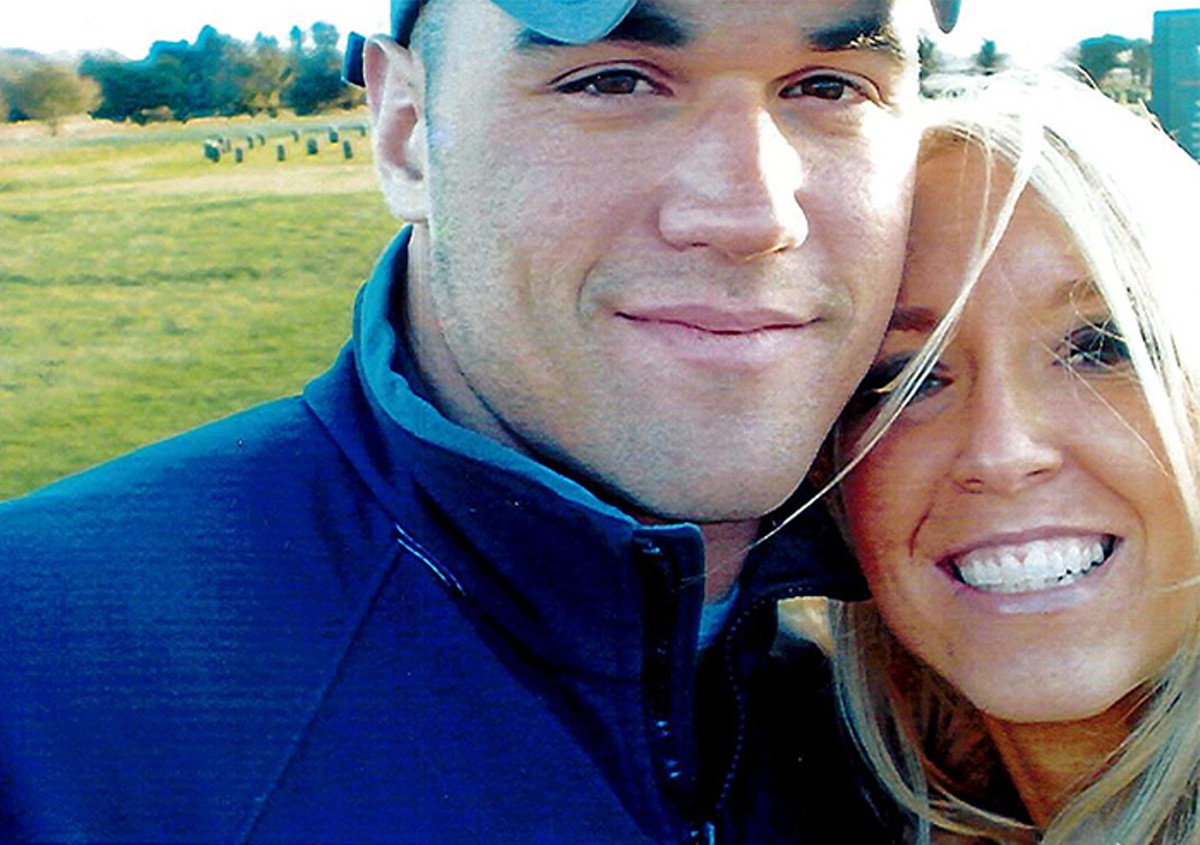

The family was studiously religious. Pope met his wife, Ashley, at a church event in Riverview when they were both 15. They married in March 2003, soon after Pope graduated from Marine boot camp. The family spent the next few years living at Camp Lejeune in North Carolina.

They moved to an upscale Commerce Township subdivision after Pope joined DynCorp in 2007, which gave the couple a $180,000 salary that afforded the move. While he was across the Atlantic, Ashley told the U.S. State Department she talked with Pope by phone at least twice a day, and the couple chatted via instant message constantly.

She'd hear all about the life on the DynCorp base. It was that environment, some employees interviewed by the State Department say, which served as a catalyst for his death.

Contrary to DynCorp and State Department policies, drinking was not only common on the base in Erbil, Iraq, but rampant. In this light, the alcohol-fueled shooting wasn't just an accident, but an end-result of DynCorp facilitating such a living space, as one employee put it. (DynCorp says in court filings that a State Department policy banning drinking on base was not "directed" at the company.)

"In my opinion, it was just a matter of time until something happened," Jeffrey Black, a DynCorp employee, said in a deposition last September. "Something — that type of behavior is not just going to continue until something bad is going to happen. It was just a matter of time."

It's also the reason, according to Palmer, why he shot someone he called his best friend, a guy he'd known since the pair met at infantry training.

Pope's death "probably wouldn't have happened if I hadn't been drinking," Palmer told Special Agent Scott Banker of the U.S. State Department on Sept. 14, 2009.

One shot

From the onset, the investigation into the aftermath of Pope's death produced a picture of a frenetic scene.

Prior to the incident, according to the State Department's file, the night of March 4 was a seemingly banal evening: Some employees went out to a restaurant for a meal. Others checked their email. Another group washed and cleaned company vehicles.

Palmer spent some time alone before the incident. Around 10 p.m. that night, he left a meeting and went to his room, popped the cork on a bottle of wine, and proceeded to watch a handful of episodes of Sons of Anarchy. He drank the wine out of a coffee cup. After finishing one bottle, he opened another.

DynCorp employee Cory Igo recalled in a deposition that when Palmer stopped by his room, he was drunk to the point of "slurring his speech" and generally very "hyper." Igo told federal agents that a group of about a half-dozen employees then moved to Pope's room and began to drink heavily.

Around 11:45 p.m., according to Igo's version of events, Palmer and Pope were wrestling on one side of the room. Soon after, a 9 mm Glock 19 was pulled out. DynCorp contends it belonged to Pope. Witnesses offer conflicting accounts of who grabbed the gun — that's the case with any number of the details in the file — but according to Igo, that man was Pope.

"Pope gave him a look of confidence that it was OK to handle the weapon and it was at this point Igo decided to move over to [the other] side of the room," the State Department's file says.

When the shot was fired, Igo said he was standing near the fridge talking to other DynCorp employees. The State Department's report says Igo recalled Pope making "a statement about the gun prior to it firing that didn't seem funny but rather sounded dangerous."

Igo couldn't clarify when asked by agents if he recalled the statement.