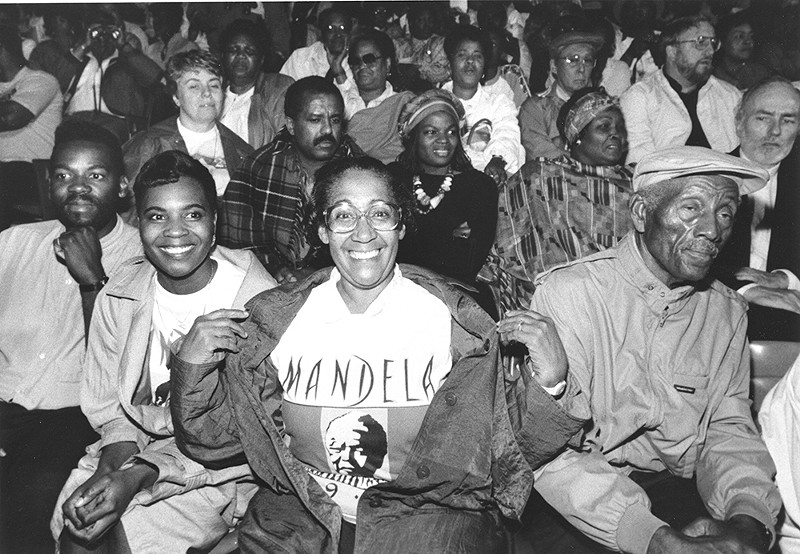

Courtesy of the Walter Reuther Library

Solidarity house: Some of the 49,000 people who came to see Nelson Mandela at Tiger Stadium June 28, 1990.

Last week we commemorated the 30th anniversary of Nelson Mandela’s historic visit to Detroit. As Metro Times readers know, South African president F.W. de Klerk freed Mandela in February 1990 after the Black anti-apartheid leader had spent more than 27 years as a political prisoner of the country’s white minority government.

In June of that year, Mandela embarked on an 11-city North American tour to bolster support for his African National Congress and to urge foreign leaders to continue their sanctions against Pretoria in the effort to dismantle South Africa’s racist apartheid system.

Shortly after he arrived at Metro Airport onboard one of Donald Trump’s short-lived shuttles, Mandela was whisked away to Corktown, where 49,000 jubilant supporters eagerly awaited his arrival.

For the 30th anniversary of Mandela’s visit to Detroit, Metro Times spoke with dozens of people who attended the rally at Tiger Stadium.

Shahida Mausi, Aretha Franklin Amphitheatre:

In the summer of 1990, Shahida Mausi was director of Detroit’s Council of the Arts. At Mayor Coleman Young’s request, Mausi planned a star-studded concert and booked the entertainment for the Tiger Stadium rally. Performers included Aretha Franklin, Stevie Wonder, the Winans, Frankie Beverly & Maze, and Dr. Teddy Harris Jr.

“We pulled that together in about three weeks,” Mausi recalls. “That was the first Ticketmaster event ever done at Tiger Stadium, so we had to just start from scratch.

“The entire thing was just illuminating,” she says. “It was elevating. “Reverend [Edgar] Vann was working hard to bring that 2,000-voice choir together for Aretha. He was bringing everything he had to bear, and everybody just gave 127 percent. You could feel the impact of that event palpably in this city for several days afterward. The way people came together. Everybody rose to the occasion to welcome Mr. Mandela.”

The Motor City, Mausi says, raised more money than any other city in the country for Mandela and the African National Congress. “That’s indicative of who Detroiters have been and the role that we’ve played in the fight for justice over decades,” she says. “Detroit led the labor movement, Detroit led the civil rights movement, and Detroit led the anti-apartheid movement. We have that as part of our DNA. That’s something that I want young Detroiters to know — we have a legacy here that is substantive.”

Regarding the racially divisive history of Tiger Stadium under former Tigers owner Walter Briggs, Mausi sees a parallel to today. “The changing of the name from Briggs Stadium to Tiger Stadium (in 1961) correlates to the changing of the name from Cobo Center to TCF Center (in 2019).”

Photographer David Turnley:

Former Detroit Free Press photographer David Turnley became a friend of the Mandela family after photographing Winnie Mandela in 1985 for an essay for Life magazine in South Africa, where he was based covering the struggle.

“I was with the Mandelas in the dining room for Madiba's first home-cooked meal, in Soweto, the first night he came home after 27 years of a life sentence,” Turnley says.

In the summer of 1990, Turnley traveled with the Mandela entourage on their first visit to the United States. When they landed in New York at JFK, the streets were lined with people as far as the eye could see. “In Brooklyn, Madiba asked the driver to stop when we passed a baseball diamond, where hundreds of Americans had gathered hoping he would speak to them.

“He got out and stood on a flatbed truck, and as he spoke about the struggle and inequalities of apartheid in South Africa, the crowd would scream in unison, ‘It’s just like that here!’ He said later that while the South African struggle had taken such inspiration from the American civil rights movement, that he had no idea the extent to which Americans of color identified with the struggle in South Africa so viscerally.

“In Detroit, I saw in the Mandelas a feeling that they felt very much at home. And one of the great moments for the Mandelas — in Detroit and throughout the entire journey — was when they met Rosa Parks. They were so happy to meet her as she was to meet them — the memory still brings tears to my eyes — it was like they had all met family.

“Detroit, of all of the cities we visited, was the one where the Mandelas felt like they were at home with such warmth from the people of Detroit. I also think that they really understood and respected the important role that Detroit has played in the American civil rights movement and the Industrial Revolution in America and the world.”

Former Detroit Free Press photographer David Turnley became a friend of the Mandela family after photographing Winnie Mandela in 1985 for an essay for Life magazine in South Africa, where he was based covering the struggle.

“I was with the Mandelas in the dining room for Madiba's first home-cooked meal, in Soweto, the first night he came home after 27 years of a life sentence,” Turnley says.

In the summer of 1990, Turnley traveled with the Mandela entourage on their first visit to the United States. When they landed in New York at JFK, the streets were lined with people as far as the eye could see. “In Brooklyn, Madiba asked the driver to stop when we passed a baseball diamond, where hundreds of Americans had gathered hoping he would speak to them.

“He got out and stood on a flatbed truck, and as he spoke about the struggle and inequalities of apartheid in South Africa, the crowd would scream in unison, ‘It’s just like that here!’ He said later that while the South African struggle had taken such inspiration from the American civil rights movement, that he had no idea the extent to which Americans of color identified with the struggle in South Africa so viscerally.

“In Detroit, I saw in the Mandelas a feeling that they felt very much at home. And one of the great moments for the Mandelas — in Detroit and throughout the entire journey — was when they met Rosa Parks. They were so happy to meet her as she was to meet them — the memory still brings tears to my eyes — it was like they had all met family.

“Detroit, of all of the cities we visited, was the one where the Mandelas felt like they were at home with such warmth from the people of Detroit. I also think that they really understood and respected the important role that Detroit has played in the American civil rights movement and the Industrial Revolution in America and the world.”

GOP strategist Wayne Bradley:“Mandela’s visit to Detroit solidified the connection between Detroit and the anti-apartheid movement and civil rights.”—Jamon Jordan, Black Scroll Network

tweet this

In the summer of 1990, Nelson Mandela and his entourage traveled across the United States on a plane owned by Donald Trump.

Rev. Wendell Anthony, president of the Detroit NAACP and emcee of the Tiger Stadium rally, calls Trump’s involvement “the irony of ironies.”

But Wayne Bradley doesn’t see it that way. “It’s not all that ironic if you look back at the real history of Donald Trump in the ’90s,” says Bradley, former state director of African American Engagement of the Michigan Republican Party.

“Back then, no one labeled him what they label him now, until he decided to run for president as a Republican. And some of that was obviously because Trump went after President Obama and the birther thing, but if you look back at Trump’s record before he decided to run for president, he was known for working with Black entrepreneurs.

“If you really look at his background — even when it comes to the reality shows and giving people like Omarosa an opportunity — I don’t think that Trump looks at race as a determining factor on whether he’ll work with you. I think the only real color he’s ever seen is green.

“If you don’t like [Trump’s] language or you don’t like that he’s abrasive, that’s fine — that’s fair — but throwing that label on there … it numbs people to reality. When you start calling someone a racist, that’s the only thing they’re gonna focus on.”

Former state Senator Coleman Young II:

“Nelson Mandela put everything on the line so that Black people could have equality and equity in South Africa,” Young says. “To see my father on that stage with Nelson Mandela — these two men who both were forged and formed through the trials and tribulations of racism, of segregation, of denial of their basic rights and humanity — it’s just amazing.

“Their struggles were really about the dehumanization and the negative stereotyping of Black people in their time. But fast-forward to today, and we’re still having that issue in the likes of George Floyd. It shows that as much progress as both of those men made — to me as a Black person with all the rights and privileges I have available to me ... we still have so much work to do. We’ve come a long way since 1990, but it also shows us how far we have to go.

“I think my father and Nelson Mandela would agree that we need justice for George Floyd and for Ahmaud Arbery and for Breonna Taylor, but we also need policies to pass at the federal, state, and local levels to make sure this doesn’t happen again. We need accountability and justice first, then policy and laws passed.”

Former Detroit police chief Ike McKinnon:

In 1990, Ike McKinnon was head of security at the Renaissance Center, where he met Nelson Mandela.

“I did not expect the kind of reception I saw there,” McKinnon says. “It was wild — the lobby was packed, the escalators, everything was packed! These people started cheering, they were crying.

“I was like, ‘My Lord, this is just incredible.’ It was a great racial mix of people, and everybody was cheering. And then all of a sudden I find myself in tears also.”

The next day, before Mandela left for the West Coast, McKinnon encountered Mandela again on his early-morning walk along the Detroit River.

“What is your job?” Mandela asked him.

McKinnon explained how he was on a leave of absence from the Detroit Police Department.

“Why did you want to become a police officer?”

“I told him my story of how I was beaten up by the police when I was 14, and that I’d made the decision to become a police officer to try and change the police culture.”

“Young man, that is a good story,” Mandela told him. “You did the right thing — make sure everybody knows that story.”

“You spent 27 years in prison,” McKinnon asked him. “Aren’t you angry?”

“Listen, in my heart, I hated all the people who imprisoned me in South Africa,” Mandela said. “But in my head, I knew it was wrong. Remember that, young man.”

“Nelson Mandela changed the world by his actions and his reconciliation,” McKinnon says. “He changed the world.”

Civil rights activist Bill Goodman:

Longtime civil rights attorney Bill Goodman sat behind home plate that night at Tiger Stadium with his father, Ernie Goodman, a civil rights attorney himself who had met Mandela and consulted with his legal team in Pretoria during the treason trials of 1956.

Goodman, whose mother was South African, had traveled to South Africa in 1963 and stayed in Cape Town with his uncle, Abram Kesler, a decorated WWII pilot in the Royal Air Force who Goodman describes as “very much anti-apartheid and pro-ANC.”

“My uncle pointed from his apartment window toward Robben Island and said, ‘That’s where Nelson Mandela is right now.’ I’ll never forget it.”

Longtime civil rights attorney Bill Goodman sat behind home plate that night at Tiger Stadium with his father, Ernie Goodman, a civil rights attorney himself who had met Mandela and consulted with his legal team in Pretoria during the treason trials of 1956.

Goodman, whose mother was South African, had traveled to South Africa in 1963 and stayed in Cape Town with his uncle, Abram Kesler, a decorated WWII pilot in the Royal Air Force who Goodman describes as “very much anti-apartheid and pro-ANC.”

“My uncle pointed from his apartment window toward Robben Island and said, ‘That’s where Nelson Mandela is right now.’ I’ll never forget it.”

Former Detroit City Councilwoman Alberta Tinsley Talabi:

“It was a magical evening — just absolutely magical. I remember the city was so excited. It was like the entire city came to a stop upon his arrival. The excitement that it generated and the hope that it generated, people were just very hopeful. We felt so special that he would come to Detroit. And the unification of the unions and city government … everyone was touched by his arrival.

“I was on the platform just taking it all in. I remember looking up and just thanking God for this moment. And for that one moment, time stood still. Everyone could not fit in the stadium, but it resonated far beyond Tiger Stadium. Much like today, we were so hopeful for the future that night.

“Detroit showed up and showed out.”

“It was a magical evening — just absolutely magical. I remember the city was so excited. It was like the entire city came to a stop upon his arrival. The excitement that it generated and the hope that it generated, people were just very hopeful. We felt so special that he would come to Detroit. And the unification of the unions and city government … everyone was touched by his arrival.

“I was on the platform just taking it all in. I remember looking up and just thanking God for this moment. And for that one moment, time stood still. Everyone could not fit in the stadium, but it resonated far beyond Tiger Stadium. Much like today, we were so hopeful for the future that night.

“Detroit showed up and showed out.”

Vanessa Ivy Rose, educator and granddaughter of Negro Leagues baseball legend Norman “Turkey” Stearnes:

Although Rose wasn’t at Tiger Stadium for the rally that day (she was only 7), she recently watched video of the event on C-SPAN. “The beautiful synchronicity of seeing and hearing Nelson Mandela on the field was a true representation of Black excellence,” she says. “His words deeply embodied the spirit of leadership, as well as the spirit of Detroit. His declarations of freedom were wrapped in ancestral healing. His calls for solidarity and unity exemplified the leadership so desperately needed in the past, present, and future. Symbolically standing in centerfield, Mandela’s words gave life, longevity, and new meaning to the whispered and unspoken dreams of a silent slugger like Grandpa Turkey. I used to think Grandpa Turkey was born too early, but seeing a liberated Mandela on the field just reaffirmed that, much like destiny, greatness has no expiration date.”

Historian Thomas Sugrue:

Thomas Sugrue, author of The Origins of the Urban Crisis, was in Detroit in the summer of 1990 and went to see Mandela with a group of friends from the UAW.

“The most powerful part of Mandela’s visit was that he bridged two key dimensions of the freedom struggle — labor and racial equality,” Sugrue says. “Nothing was more moving than seeing him and Rosa Parks together connecting civil rights, Black power, and the global struggle for racial justice.”

Cynthia Lindsey, attorney on the Flint water case:

“It was one of the most monumental events of my lifetime,” Lindsey says. “My little sister Deborah Folson and I — when we got to Tiger Stadium, it was half filled. We waited for hours, but it didn’t matter. We didn’t care if they didn’t show up till midnight! And when Nelson Mandela finally arrived and said, ‘Hello, Motortown!’ it was like I had been transmuted from a human body to a spiritual body somewhere in outer space.

“We didn’t walk across the bridge in Selma, we didn’t march with Martin Luther King — this was our MLK march.”

Darrel Drobnich, former aide to Sen. Carl Levin:

In June of 1990, Darrel Drobnich had just started working for U.S. Senator Carl Levin, whose office was right down the street from Tiger Stadium. Drobnich and his coworkers walked to the rally from the McNamara Building on Michigan Avenue.

“People never thought they’d see Mandela alive,” says Drobnich, now a nonprofit consultant in Washington, D.C. “Him being released was a validation of the peace movement — validation that protest could work, that sanctions could work.”

“Everyone deserves freedom and peace,” Drobnich says. “If this guy came out of prison angry, you wouldn’t have held that against him. All the Afrikaners were afraid of mass riots and slaughters and revenge, but Mandela totally turned it around. He totally embraced Gandhi and Martin Luther King — that really struck a chord with people, and he never wavered from that message.”

Stay on top of Detroit news and views. Sign up for our weekly issue newsletter delivered each Wednesday.