The battles over Enbridge Energy's Line 5 pipeline and proposed tunnel project continue to escalate.

For more than a year, archaeological discoveries in the Straits of Mackinac have caused concerns not only among field experts and environmental activists, but especially among Indigenous tribes because the history of their cultures is potentially at stake.

At its basis are laws provided to multiple tribes under the umbrella of the Chippewa Ottawa Resource Authority, as part of the 1836 Treaty of Washington. The tribes include Bay Mills Indian Community, Grand Traverse Band of Ottawa and Chippewa Indians, Little River Band of Odawa Indians, Little Traverse Bay Bands of Odawa Indians, and the Sault Ste. Marie Tribe of Chippewa Indians.

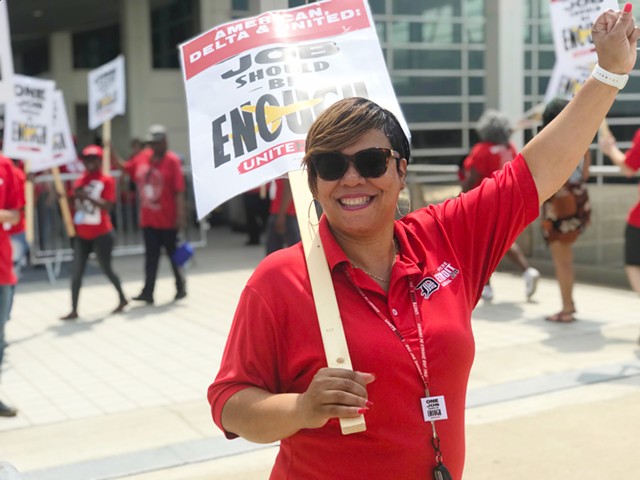

Andrea Pierce, chair and founder of the Anishinaabek Caucus of the Michigan Democratic Party and member of Little Traverse Bay Bands of Odawa Indians, joined tribal members and environmentally conscious brethren to investigate.

"I didn't believe that everything we were being told about Line 5 was true, and I really wanted to see for myself," Pierce says.

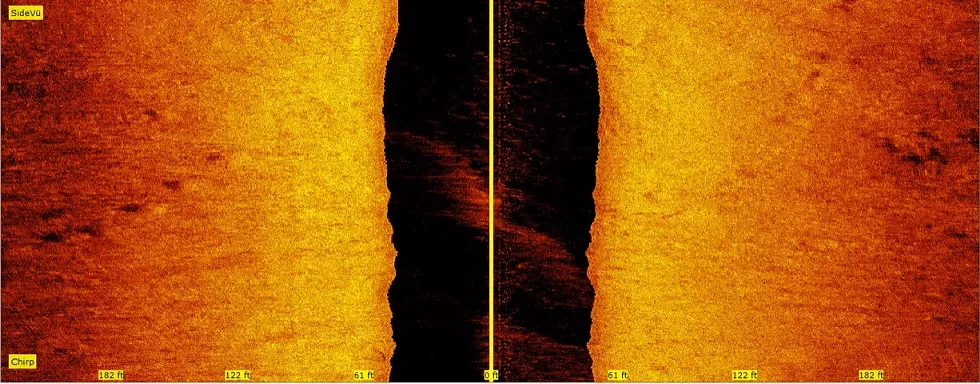

Water advocates like Andrea Pierce, Terri Wilkerson and Little Traverse Bay Bands citizen Fred Harrington, Jr., arranged for side-scan sonar to see if something was amiss.

"That was our first tip-off that there might be something of archaeological interest," says Wilkerson, who runs RetireLine5.org.

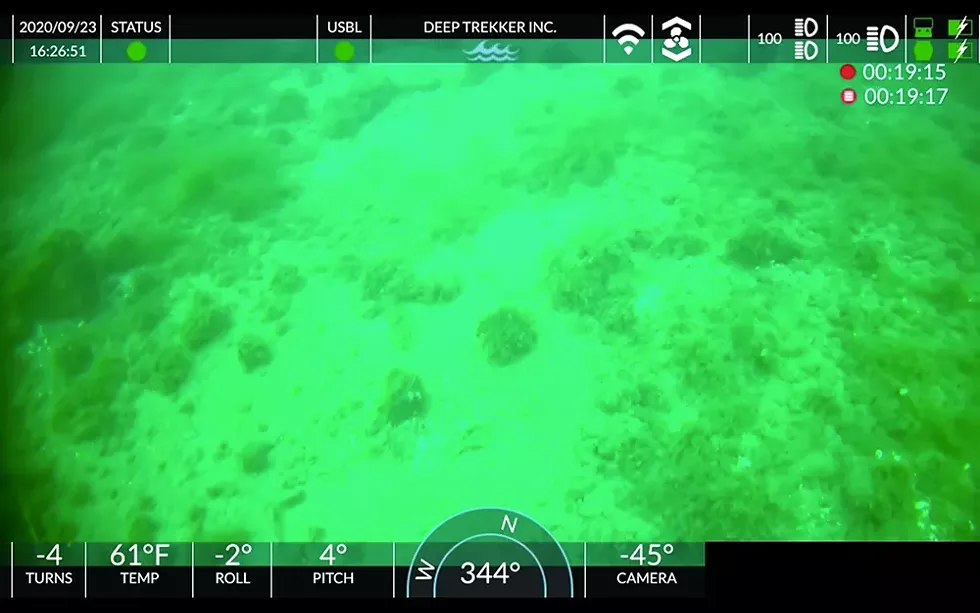

Harrington suggested the group acquire a remotely operated vehicle, or ROV, that could be better controlled and produce reliable underwater images.

Wilkerson, who acquired a work permit to travel from Mackinaw City to Toronto to pick up the ROV, later went on the water with Harrington and another individual. Harrington was in control of the ROV, "dropping" pins and forming a high-concentration data cluster.

Video footage and photographs taken during the excursions revealed a circle of stones thought to be part of a cultural site from as far back as 10,000 years ago, near the end of the Ice Age.

"It's not just one little circle we're talking about," says Wilkerson, a retired real estate broker from Pinckney. "It's quite expansive. We're not talking about a 20-by-20-foot area."

Similar rock formations have been located near Grand Traverse Bay and Beaver Island.

"We kept it quiet; we didn't tell a lot of people," Pierce says. "It was a very secret operation because we didn't know what we were gonna find. ... This is not an accident."

'It's real and a concern'

John O'Shea is the curator of Great Lakes Archaeology at the University of Michigan Museum of Anthropological Archaeology, as well as a professor in the university's Department of Archaeology.

He has worked as a curator since 1982, looking after archaeological collections the university holds from the Great Lakes while conducting original research, including investigating shipwrecks and submerged landscapes.

While working in the middle of Lake Huron at Alpena Ridge, he discovered old campsites that showed evidence of caribou hunting.

He says that about 10,000 years ago that area would have been dry land with potential rivers connecting the Michigan and Huron basin. He had not previously worked in the Straits.

"It's just me knowing the symmetry, the lake levels, and time period," O'Shea says.

Of the boulders he found on Lake Huron: "No question it's real and a concern."

"The archaeology is rock solid," he says. "We've peer-reviewed in multiple journals, including the National Academy of Sciences. It's kind of a hard situation. The work we do is under permit by the state, so our work is vetted by the state and stakeholders. Often, we're put in the position to do the evaluations. ... If you're gonna perform that role, it's very difficult to be a political advocate for or against it at the same time."

At an annual Society for Historical Archaeology meeting in January 2020, O'Shea ran into an acquaintance who inquired about any possible connections between Line 5 and cultural artifacts.

O'Shea returned to Ann Arbor and wrote a letter that February to the Michigan State Historic Preservation Office (SHPO). "All I was trying to do was raise the yellow flag," he says.

"This entire story is very disturbing," O'Shea wrote. "The cultural deposits which are very likely present and visible in the secondhand sonar imagery are about as significant as a site could be, given the small number of sites from this time period on land, and would be unique as the first instances to be documented off and beyond the Alpena-Amberley Ridge in Lake Huron.

"At the same time, the sites are extremely vulnerable to disturbance and would be obliterated without a trace by the proposed tunneling," the letter continued. "These are a unique piece of Michigan's past that should not simply be brushed aside and destroyed."

The letter's delivery, however, was "ill-timed" due to COVID-19; it wasn't circulated until August.

A request for expertise

On Nov. 10, 2020, SHPO senior archaeologist Stacy Tchorzynski sent her own letter to the Michigan Department of Environment, Great Lakes, and Energy (EGLE).

"This area is sensitive for the presence of terrestrial and bottomland archaeological sites (including historic aircraft and shipwrecks), submerged paleo landscapes, cemeteries and isolated human burials, significant architecture and objects, and historic districts," Tchorzynski wrote, adding that some sites could be eligible for or listed in the National Register of Historic Places.

"Survey for significant cultural resources in the Straits is incomplete, and we expect numerous additional resources to be present that have yet to be reported, documented, and evaluated."

She added that the state's cultural resources review team should include SHPO staff, as well as relevant subject-matter experts, in areas like terrestrial and underwater archaeology, geology, and geomorphology.

"We've identified concerns, as well as gaps in existing data that support the need for additional cultural resources surveys," Tchorzynski concluded her letter.

Court battles

Christopher Clark is a supervising staff attorney who represents the Bay Mills Indian Community on behalf of Earthjustice.

"The pipeline presents a terrible risk, a calamity, that will deeply affect resources the tribes have protected by treaty," Clark says, adding that approximately 50% of Bay Mills households' income is derived from fishing. "The region itself has a very deep and historic cultural significance to Bay Mills and the other tribes. The Straits of Mackinac figure prominently in the tribes' creation story."

The organization's work falls into three broad categories: advocating for a healthier environment and addressing environmental justice; protecting and preserving natural landscapes, resources, plants, and animals; and addressing climate change.

"EGLE should not have issued that permit in light of the recommendation in that SHPO letter," Clark says. "As an agency of the state, I think EGLE has an obligation to closely examine the impact of this project in the environment and the resources protected. Essentially ignoring the recommendations of SHPO does not comply with those obligations."

Earthjustice and its co-counsel, the Native Americans Rights Fund (NARF), have gone back and forth in court filings with the Michigan Public Service Commission and Enbridge as it pertains to three main legal interventions: urging the commission to examine the need of Line 5 and its continued operation for decades to come; understanding the risk presented to a pipeline that crosses approximately 300 waterways across upper Midwest states; and the overall effect on greenhouse-gas emissions and climate change.

During an April 21 hearing, after multiple decisions and appeals, the MPSC recognized that climate change must be considered in evaluating the tunnel. However, the concerns of the tribal nations were ignored.

"Today's decision is a mixed bag," NARF staff attorney David Gover said April 21. "We are glad to see the progress made on the inclusion of evidence pertaining to climate change, but remain concerned that the commission fails to acknowledge that treaties are the supreme law of the land and must be honored."

Enbridge's vow to protect

On Nov. 13, 2020, Gov. Gretchen Whitmer and Department of Natural Resources director Dan Eichinger notified Enbridge that the 1953 easement for Line 5 would be revoked and terminated, and that operations must cease by May 12, 2021.

Enbridge spokesperson Ryan Duffy says the company "is committed to protecting cultural and archaeologically significant features in the Straits as we advance the Great Lakes Tunnel Project," adding that it has a "desire" to work with tribal communities and historic-preservation offices "to identify sensitive cultural sites and artifacts and together plan for their protection."

The company plans to build the tunnel 60 to 250 feet below the lakebed, Duffy says, alleging no direct impact to the lakebed.

EGLE spokesperson Nick Assendelft echoes Duffy's statement, saying the lakebed will not be worked on without water intakes and outfalls.

“Seriously, this was people in a canoe who found this. None of us are archaeologists.”

tweet this

Lawsuits filed by Whitmer, Nessel, and Eichinger remain pending and are public record. In November, when revoking the easement, Whitmer for the first time officially acknowledged the tribal treaty.

"The State has not shown that Enbridge is out of compliance with the easement agreement, and Line 5 continues to operate safely, as determined by PHMSA, the safety regulator of interstate pipelines in the United States," Duffy adds. "The administration and Enbridge are engaged in court-ordered mediation. Enbridge favors the mediation process and believes it is an opportunity to resolve issues. We take it seriously and are optimistic the process will enable the parties to address key matters in dispute and to find common ground."

Assendelft says EGLE met early on in the permit application review process with tribes "to receive their initial concerns."

"After the department received the letter regarding cultural artifacts, it was immediately shared with the tribes," he says. "EGLE worked with [the] State Historic Preservation Office to craft language to be included within the permit, which requires further work regarding cultural surveys prior to any work occurring on the lakebed itself."

Enbridge is currently awaiting a permit from the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers.

Hoping for change

Enbridge's Line 6B ruptured on July 25, 2010, and saturated approximately 40 miles of the Kalamazoo River. The only bigger spill was in March 1991, also from an Enbridge pipeline. To this day, that incident in Minnesota remains the largest inland oil spill in U.S. history.

Pierce says "it's really hard to have faith" in EGLE after it approved permits earlier this year after cultural concerns were previously brought to its attention.

"How is that even possible?" Pierce says. "Why is EGLE not operating in our best interest? We don't want our history destroyed before we even learn about it.

"If normal citizens can find (cultural sites), how can a multi-billion-dollar company not discover it? Seriously, this was people in a canoe who found this. None of us are archaeologists."

She expresses a lack of optimism with regard to court battles, due to Enbridge's financial power and legal resources.

"I'm still hoping we can protect it," Pierce says. "We didn't know it was there, and now we do — and that really changes things. ... People don't seem to care about our history as much, and I think we need to work towards changing that. I think we need to claim our history and learn more about it."

Clark says Whitmer and Nessel are fulfilling their responsibilities and exercising their obligated authority to protect resources.

"My optimism comes from the numerous voices from tribal nations, organizations, environmental advocacy groups, and concerned individuals that are raising a wide array of issues and concerns that are critically important," he says.

If May 12 comes and goes and Line 5 remains running, Wilkerson says a physical demonstration could occur.

"I think if Enbridge tries to build the tunnel, we will see increased resistance and support from across the country from people who don't want to put our Great Lakes at risk," Wilkerson says. "I hope that it never comes to that."

Pierce goes even further: "We will have our own Standing Rock."

"There's a lot of people watching and aware of what's going on," she says. "If they don't shut it down, it will show how powerless our government is here in Michigan."

Stay connected with Detroit Metro Times. Subscribe to our newsletters, and follow us on Google News, Apple News, Twitter, Facebook, Instagram, or Reddit.