Updated at 5:45 pm on Tuesday, March 7: This post has been updated to include details of the investigation into the August 2015 shooting involving Officer Jerold Blanding, which were obtained through the Wayne County Prosecutor’s Office on March 7 through a Freedom of Information Act request.

Originally posted at 7:05 am on Friday, March 3:

The Detroit police officer who shot and killed a 19-year-old last month after what officials say was a physical altercation has allegedly been involved in at least two other non-fatal shootings that have prompted unjustified-use-of-deadly-force lawsuits against the department.

Sources close to Detroit police have identified the shooter as Jerold Blanding, an officer whose Instagram handle was “Fatal Force” at the time of the killing. Police officials have not named Blanding, but describe the officer who killed Raynard Burton on Feb. 13 as an African American man who has been with the department for 22 years.

Blanding shot Burton after initially seeing him speed by in what police later said was a stolen vehicle that the teen had obtained in a carjacking. A foot chase led the pair behind an abandoned building where police say a scuffle ensued and Blanding fired a shot into Burton’s chest, killing him.

Investigators have had little to go on beyond Blanding’s account of the events: the shooting, they say, occurred far from view of his cruiser’s dash camera and he wasn’t wearing a body camera at the time because his precinct had yet to receive them. What’s more, the Dexter-Davison area block where the shooting occurred was lined with mostly abandoned homes and there were no witnesses to the incident.

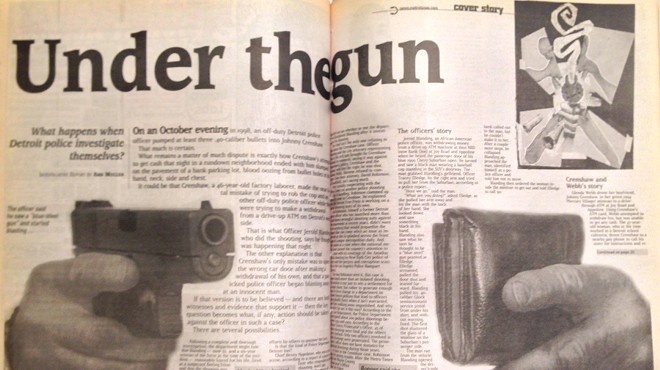

The week of the shooting, Metro Times reported that Blanding has a violent past that could throw his credibility into question. According to court records, in 1998, Blanding repeatedly shot a man who had appeared to have just gotten money out of an ATM and accidentally opened the door of the wrong vehicle after walking away from the cash machine. Blanding was off-duty at the time and told investigators he thought the man was an armed robber. However, a woman who had helped the victim get money out of the ATM corroborated the man’s claim that Blanding only started shooting after he apologized for his mistake and closed Blanding’s car door.

Blanding was never charged, but Detroit police failed to seek out that witness during their investigation and used leading questioning in an apparent attempt to help Blanding avoid punishment. The handling of the case helped lead to what would end up being 13 years of federal oversight of the DPD.

While he wasn’t disciplined for that shooting, a 2000 report by the Detroit News says Blanding was disciplined in 1995 for shooting a pigeon with his department-issued Glock.

Now, a fourth incident alleged to have involved Blanding has come to light. This time, the officer who calls himself “Fatal Force” is accused of pumping about 15 bullets into a vehicle being driven by a man who says he was unarmed.

The 2015 incident is the subject of a civil rights lawsuit filed against Blanding, two other officers, and the Detroit Police Department. It comes after the Wayne County Prosecutor’s Office declined to file charges in the case, determining that Blanding had acted “in self-defense and/or the defense of others.”

We’ll begin with victim DeMar Parker’s account of the August night in question, then pick up with Blanding.

The series of events that would put Parker within inches of losing his life were set into motion when he stopped by the home of the mother of his child and saw through a window that a 10-year-old boy was inappropriately touching his four-year-old daughter. Parker says he and the girl’s mom got into a heated argument when she refused to break the kids up, and he called her father for help. At some point after the woman’s dad arrived to diffuse the situation, so did the woman’s boyfriend and father of the 10-year-old boy — Officer Christopher Townson of the Detroit police.

Parker says Townson approached him aggressively, asking “What’s your problem with my son?” and flashing his service weapon. Moments later, two other uniformed officers showed up and the group began to close in on him.

Frightened, Parker ran to his car and took off. He drove a few blocks until he felt he was out of harm’s way and turned the car around to head back in the direction of his home. He says he decided to return using the same road in an effort to get the license plate number of the Ford Taurus in which the officers had shown up.

As Parker headed back down the street, he says one of the officers stepped into the middle of the road and pointed his gun directly at him. Parker swerved to avoid him when he says an officer who’d been standing on the sidewalk suddenly opened fire.

Parker ducked as he says Blanding shot repeatedly at his vehicle, sending bullets whizzing past his head. One of the bullets hit his leg.

“I never expected it,” Parker recalled during a recent interview with Metro Times. “There was definitely fear in that moment. Time kind of slowed.”

According to the suit, Blanding sent approximately 15 bullets into Parker’s vehicle by the time he was done firing, the same number of bullets that can be found in a full magazine in a Smith and Wesson .40 caliber Glock — the standard issue weapon of the Detroit Police Department. The lawsuit alleges that those bullets were “aimed and intended to kill” Parker.

Blanding, for his part, claims that Parker had come back down the street waving a pistol and that he feared Parker would shoot his fellow officer or hit him with his vehicle. Blanding was the only witness to claim Parker had a gun.

Others who were interviewed by detectives only spoke to the manner in which Parker approached the officers in his car. A neighbor says she saw Parker drive up slow in an attempt to “intimidate” the officers, while the grandfather of Parker’s child— who was inside at the time— says he heard a “loud engine” come up the street. The officer Parker said was standing in the middle of the road with a gun claims he stepped out of the way so the vehicle could pass but that Parker accelerated and veered towards him, causing him to jump out of the way. Blanding claimed he heard squealing tires.

Everyone questioned claimed Parker had been acting erratically in the lead up to the shooting, while each of the off-duty officers claimed he had verbally threatened them.

The prosecutor’s office never charged Parker due to insufficient evidence.

Parker says that a week after the shooting, internal affairs investigators and homicide detectives at police headquarters told him that DPD would launch an internal investigation to examine the actions of the officers. Detroit police spokesman Michael Woody, who would not comment on the case because of the lawsuit, did confirm that an investigation had been opened, though he wouldn’t say when and declined to divulge its status.

For now, what is known is that after the August 2015 incident, Blanding was able to remain on the force all the way through February of 2017 when he killed somebody, and is still a Detroit police officer today.

“When I found out it was Blanding [that shot Burton] I feel like it validated what was going on with me even more for people that had suspicions of what could have been,” said Parker, who learned Blanding was the officer who killed Burton through media reports. “And then you see his history and, it’s like — this guy is a hothead. My question is, what type of help is he receiving after these situations is happening? How is the force following through with him being out here?”

Parker’s lawyer Sarah Prescott says DPD’s approach, thus far, has been to turn a blind eye to the problem that is Blanding.

“It’s essentially become known that they aren’t going to do anything,” said Prescott. “I would feel better if I knew ... people had gone on the record and said maybe we did a psych examination, or we qualified him, or trained him, or we did our homework and really followed up and took this seriously. A person was shot and could have been killed, you know, we took that seriously. And I just do not have that sense. I haven’t seen anything like that out of the department.”

DPD’s approach, thus far, has been to turn a blind eye to the problem that is Blanding.

tweet this

For now, Blanding is on routine restricted duty for killing Burton, but will be back on the streets if the Wayne County Prosecutor’s Office declines to bring charges against him. The office says the case is currently under review. The Detroit Police Department, which led the investigation into Burton’s death, handed its findings over to the prosecutor on Feb. 21.

Detroit police declined to say what, if any, steps have been taken to help or discipline Blanding in the past. The department says it does track uses of force by officers through a database it refers to as an “early intervention system.” Woody says the system is essentially designed “to identify an officer who is likely to engage in potentially damaging behavior before the behavior occurs.” It was adopted in 2008.

It’s not uncommon for the department to give special supervision to officers like Blanding, says Detroit Board of Police Commissioners Chairman Willie Bell.

“We have identified officers in the past who might have problems, whether it be citizen complaints or red flags go up, and there’s a great deal of monitoring and counseling that would try to go into those situations,” said Bell.

The Detroit Coalition Against Police Brutality says that in the case of Blanding, however, such an approach would not go far enough.

“This guy should not be on the force,” said Chris White, the watchdog group’s director of operations. “He has proven over a 22-year period to be an extremely hostile individual.”

Blanding, White says, has been able to remain a Detroit cop because the department is more concerned with protecting its reputation than weeding out rogue officers.

“It’s an issue of transparency,” said White. “It’s time to stop trying to cover up this type of behavior because the mayor is up for re-election and it’s time to address this issue head on because we have no idea how many officers of this nature are still on the force.”

But firing an officer who has not been charged with a crime is next to impossible, says Bell. The department just this decade had an officer within its ranks who had shot nine people and killed three of them over the span of six years, forcing the department to pay out more than $7 million in lawsuit settlements. It was only after DPD accused Eugene Brown of payroll fraud that he exited the department. But Brown left on his own terms: he retired and is likely still receiving a pension.

Blanding, so far, only appears to have cost the department six figures. That’s how much the lawyer who represented Crenshaw says the city paid to settle the suit he brought against the department after Blanding’s off-duty ATM shooting in 1998.

David Robinson is a lawyer who has handled hundreds of police misconduct cases over the past 30 years, and says more than a decade of federal oversight hasn’t had much effect when it comes to DPD officers’ use of force. “Has the Detroit Police Department cleaned up its act? Absolutely not,” he says.

Robinson has a unique perspective on why some officers might be more likely to pull the trigger than others, because in addition to his role as a lawyer defending the victims of police shootings, he’s also a former Detroit cop and attorney for the department. Robinson served for 13 years and says he never had to use force.

“What motivates someone like Blanding to forget about his sworn responsibility not to shoot somebody who is no longer a threat?” asked Robinson. “Is it a mistake? I don’t think so. Is it unjustified fear? In large part I think so. Is it in intentional? In some of these cases, yes.”

For Robinson, Blanding and Brown were accidents waiting to happen.

“Has the Detroit Police Department cleaned up its act? Absolutely not.”

tweet this

“The only way to address officers like that is to actually pay attention to their histories, which apparently isn’t the case with Blanding and wasn’t the case with Eugene Brown. And that’s why you have these repeat circumstances and individuals being shot and killed by officers like Mr. Blanding.”

But just because an officer has shot people on multiple occasions, it doesn’t necessarily mean the department considers the officer a risk to the public.

“Each case is investigated on its own merit,” Woody told a local daily paper last month after Metro Times brought the 1998 incident to light. “If there are any factors that are of concern (in the earlier shooting), they will be brought to the forefront and addressed.”

Woody wouldn’t comment to Metro Times now that Blanding has turned out to be the triggerman in more than one earlier shooting, but embattled Police Officers Association President Mark Diaz did.

“Because an individual, police officer or otherwise, is ever, at any point in their lifetime, in a situation that requires them to use fatal force, that does not shield them from being in a like situation ever again,” Diaz said in an email after he was charged with malicious destruction of property and suspended from the department.

For Blanding’s latest known living victim, the hope is that the officer who calls himself Fatal Force will never be in a “like situation ever again.” But if that does end up being the case, Parker hopes Blanding will have at least received the proper help first.

“We need police out here to help us out and keep our city safe and our streets safe,” said Parker. “He doesn’t need to ... be reacting to situations in this manner. Whatever type of help there might be to improve his decision making under pressure, he needs that.”