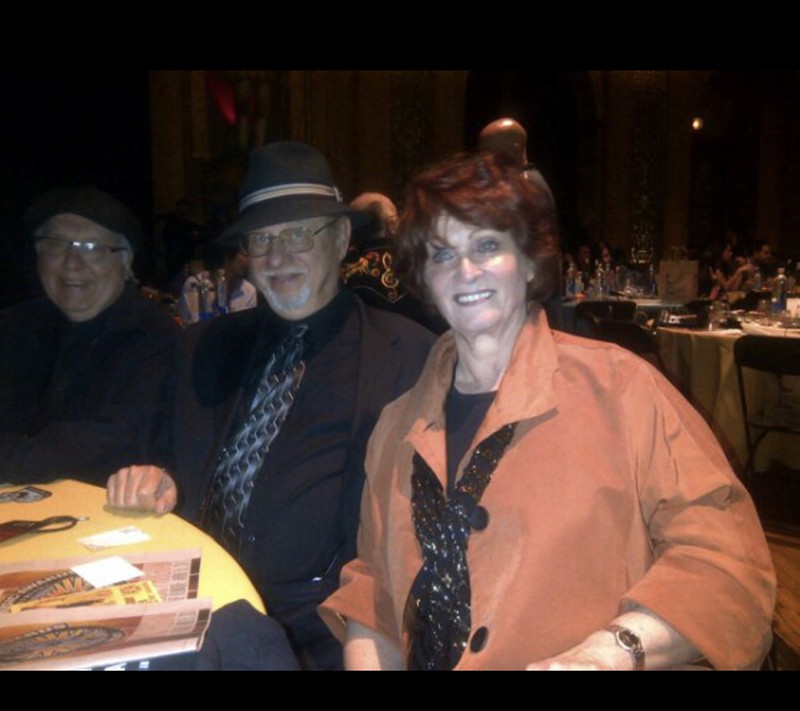

Courtesy of the family of Millie Coffey

Millie Coffey with husband Dennis Coffey at the Detroit Music Awards.

Millie Felch Coffey is seated in a green room at NBC Studios in New York, where her husband, legendary Motown “Funk Brother” guitarist Dennis Coffey, is preparing to sit in with Jimmy Fallon’s house band, The Roots. “One of the NBC employees came in wearing this gold peacock badge, apparently a symbol of his seniority,” Dennis recalls.

“Millie looks at him and says, ‘Oh, I have to have that.’ He says, ‘You can’t have this! This is my corporate badge. I can’t give you my badge!’ She made this guy feel so guilty, he came back later and said, ‘Oh, you’re right. You can have it. I’ll tell them I lost it.’ That’s how she would do it. She was an amazing woman.”

The consensus among those who knew her is that very few people ever said no to Millie Coffey, a behind-the-scenes legend in Detroit’s recording and broadcasting communities who died June 10 of complications from Alzheimer’s disease at the age of 72. “You couldn’t, even if you wanted to,” says her daughter, Jillian Frederick. “She had such a loving, wonderful, laughing way about her, you would end up doing what she wanted just to make her happy.”

A vivacious presence across Detroit’s musical spectrum, Millie worked in A&R (artists and repertoire, part talent scout, part artist liaison) for Motown Records shortly after graduating from Mumford High, continued to showcase her record industry skills in Los Angeles, then returned home to become a standout sales and marketing professional for several classic radio stations — including Windsor’s CKLW at the height of its Top 40 dominance and WLLZ-FM in its rock ’n’ roll infancy.

Yet her most enduring legacy may be as an initiator of the annual Detroit Music Awards, which celebrated its 28th year in April, and the driving force behind the Detroit Radio Reunions that brought hundreds of our memorable broadcast talents back to the city for weekends of memories, fun and fellowship.

“She came into my office one day and said, ‘We’re going to have a thing here like the Grammy Awards,’” relates Allan Wilson, the retired veteran radio executive who hired Millie for his sales team as general manager of Detroit’s KISS-FM. “I said, ‘Good luck.’ The thing about Millie was, she always wanted to have reunions.

“She said, ‘No, you don’t understand. We have media people and record people on board, but we need a radio guy. You’ve got to do this.’

“I said, ‘I am not doing this. No. Absolutely not.’

“Millie said, ‘Just hear it out. We’re all going to go to lunch and toss some ideas around. Come join us.’ That was it. I was screwed! I finally said OK. That’s how the Detroit Music Awards started. I didn’t want to do it, and I’m still doing it.”

The fact that some of the original DMA creators, like Wilson and longtime Detroit music journalist Gary Graff, are still involved with the event may be a testament to Millie’s persuasiveness. Her daughter says she had a way of making difficult challenges seem like simple tasks.

[image-3] “When she found out I liked to sing and was good at it, she said, ‘Let’s go out and try an audition,” Frederick remembers. “I’m like, ‘OK, cool,’ so we walk into this huge building that’s just gorgeous and Mom says, ‘Now just go up on stage and sing the song we practiced.’ The audition was for the touring cast of Les Miz! She made me go up on the Fisher Theatre stage at six years old for my very first audition, singing ‘Castle on a Cloud.’ I did not get the part.”

Says Frederick of her mother, “She passionately lived life through music. When a song came on the radio she could tell you the year it came out, how old she was, and whose basement she was in when she and her friends danced to it. She instilled that love of music in me.

“Most importantly, especially for being in Detroit, and white, and Jewish, she believed it didn’t matter what color you were, what social class you were in or what faith or religion you followed. Music connected us all.”

Music wasn’t always kind to her, however. “She was convinced that at some point she was going to be a Motown artist,” says Terry Bommarito Holmes, onetime event planner for MTV Networks and Millie’s longtime confidant. “But when she was out in LA, she worked for a while as assistant to Mac Davis, the singer. He was recording an album, they needed some people to clap in the background for a certain song, and Millie happened to be there.

“She went into the studio, and midway through the session they had to stop recording and ask her to leave. She couldn’t clap on the beat.”

Millie Coffey may not have made it as a singing — or clapping — sensation, but Holmes says it’s not surprising she believed she could.

“It never occurred to her she couldn’t go into a business, that she couldn’t do something because she was a woman,” Holmes says. “At a time when women were not doing such things, it never even dawned on her. She just went where she wanted to go, did what she wanted to do. She was an inspiration.”

Those who wish to honor the memory of Millie Felch Coffey may do so by making a contribution to the Alzheimer’s Association (alz.org) or to the charity of your choice.

Stay on top of Detroit news and views. Sign up for our weekly issue newsletter delivered each Wednesday.